What if… the two-day weekend was made permanent?

Starting May 15, the government introduced a two-day weekend holiday, purportedly to reduce fuel consumption and stabilize the country’s foreign exchange reserves through less fuel imports. In these two weeks, there is no sign the decision has reduced public mobility or curtailed fuel consumption.

As fuel prices rocketed in the international market, they soared in Nepal as well. According to the Nepal Oil Corporation (NOC), the country currently consumes 150,000 kiloliters of diesel and 60,000 kiloliters of petrol a month, with a total burden of Rs 30bn on the exchequer. The state oil monopoly had projected, based on scant evidence, that the two-day public holiday would cut fuel consumption by 35 percent.

The NOC is already regretting its decision and the government is said to be mulling reinstating the six-day workweek.

Pushkar Karki, joint spokesperson of the oil monopoly, says there has been no meaningful reduction in average fuel consumption on Saturdays and Sundays. “If public mobility on these off-days remains as it is, we might as well roll back the two-day holiday provision,” he says.

The present two-day weekly off arrangement was spurred by economic necessities. But what if the situation were normal? Would the two-day weekend work in Nepal?

No, say the experts and officials ApEx talked to. In fact, they add, it will if anything adversely affect the economy of a developing country like Nepal.

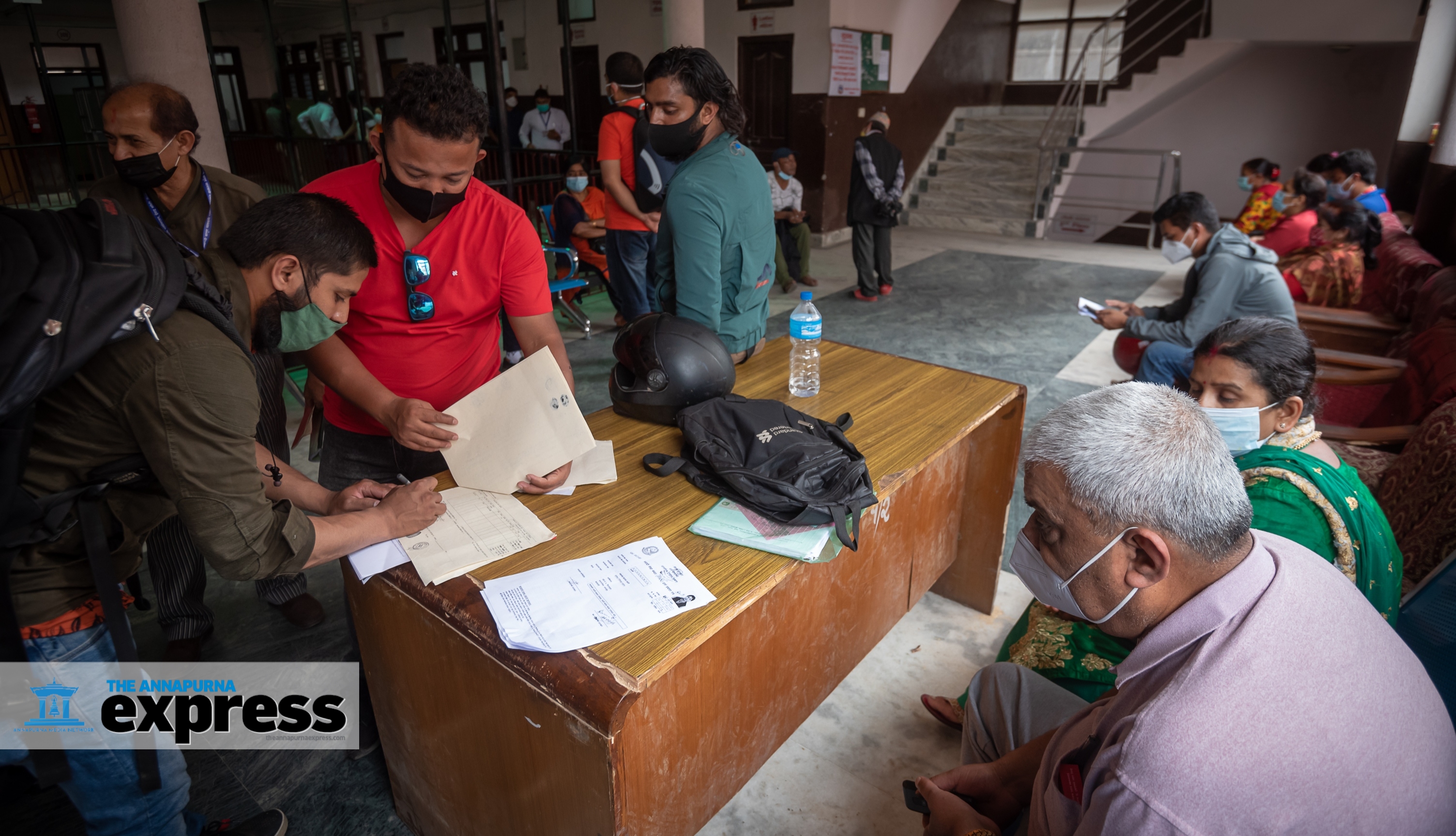

Local governments, public institutions, schools, universities, and private sector bodies have already announced that they will not follow the government decision on the two-day weekly holiday. They say it would otherwise be difficult for them to sustain normal business.

They have a point. There are 52 Saturdays and as many Sundays in a year. Add to that 22 national holidays. This takes the total holiday count to 126 a year.

With that many public holidays, hardly anything will get done, says Chandra Mani Adhikari, an economist.

“There is no need for so many holidays. The two-day weekend decision has no scientific basis. If anything, it will make service-delivery worse,” he says.

In countries where the five weekdays provision is practiced, one extra day out of office is believed to give workers enough time to rest and recharge their batteries.

“Nepal, however, does not have the luxury enjoyed by those developed countries,” says Chakra Bahadur Khadka, an expert on petroleum products. “This is the time to work more and balance the economy. For that, we need to start using petroleum products on more productive ventures.”

This is not the first time Nepal has toyed with the idea of a two-day weekly off. It has already been experimented twice—in 1990 and in 1999.

The experiment was unsuccessful each time. Service-delivery was crippled as bureaucrats started leaving their offices early on Friday and coming late on Monday. “The public was soon up in arms against the new system,” remembers Kashiraj Dahal, an administrative affairs expert.

In 1990, the offices affiliated to the judiciary were the first to practice it, again to woeful consequences to service-delivery.

Then, again in 1991, the then Administration Reform Commission recommended a two-day weekend to reduce load-shedding and energy consumption.

The government of Prime Minister Krishna Prasad Bhattarai implemented the recommendation in Kathmandu valley fully eight years later, in 1999. Again, it was rescinded less than a year after its introduction.

The same tried and failed approach is yet again being implemented.

In 2020, the then Minister of Culture, Tourism, and Civil Aviation Yogesh Bhattarai had formed a committee to study if a two-day weekly holiday could increase internal tourism that was battered by the Covid-19 pandemic.

The report said that even if 10 percent of the almost 8m people who would get an extra day off went out on that day, local tourism would get a boost.

The committee had studied 127 countries, 116 of which practiced a five-day work week. Of the 43 countries in Asia under study, 38 had five weekdays. Among the SAARC member states, Nepal was the only country with a one-day weekend.

The 2020 research committee found that the international practice of two-day weekend helped workers relax and concentrate more at work. The report said that those countries had strictly implemented working hours on other days so that service-delivery wouldn’t be affected.

Before the committee’s findings could be put to use, the country was hit by another wave of Covid-19. The findings were then forgotten.

“We in Nepal cannot even ensure our civil servants are in office in the days and hours they should be. In this situation, implementing a two-day leave system will be filled with challenges,” adds Dahal, the administration affairs expert. He is thus unsure that a permanent five-day week is a viable option in Nepal.

It is noteworthy that every time the government has proposed or considered five working days, it has always come as an expedient to shore up a failing economy. Improving workers’ productivity or their mental health has never been the priority, unlike in more developed countries where the two-day weekend is in place.

Economist Dilli Raj Khanal also does not believe that the new provision will in any way reduce fuel consumption. “It would be better to look for other alternatives to increase forex, for instance by reducing petroleum consumption in government offices and projects.”

He also adds that longer weekly holidays will push back the deadlines of national projects, ultimately harming the national economy.

Unless the citizens are conscious of their behavior, Adhikari says, such arbitrary government rulings alone won’t mean much.

The two-day weekend plan will succeed, suggest administrative affairs experts, only if Nepal improves its work culture and packs the things done on Sundays in other working days.

Mahadev Panthi, spokesperson for the Office of Prime Minister, says the two-day weekly off decision is just in the second week of the trial phase, and it is difficult to speculate about its effectiveness this early into its implementation.

“We are in constant touch with the chief district officers and collecting feedback on the new system’s effectiveness. It’s an ongoing process,” he says.

related news

What if… the left electoral alliance is revived?

April 1, 2022, 9:22 p.m.

What if… the fast track project was completed on time?

March 18, 2022, 9:32 p.m.

What if… Kathmandu valley had a metro service?

March 5, 2022, 5:34 p.m.

What if… voters got to reject candidates?

Feb. 18, 2022, 9:54 p.m.

What if… we didn’t need the National Assembly?

Feb. 6, 2022, 12:06 a.m.

What if… Kathmandu had more open spaces?

Jan. 22, 2022, 5:34 p.m.

What if… (local) elections cannot be held on time?

Jan. 7, 2022, 6:03 a.m.

What if… the 1923 Nepal-Britain treaty was not signed?

Dec. 25, 2021, 7:37 a.m.

Comments