What if… Kathmandu valley had a metro service?

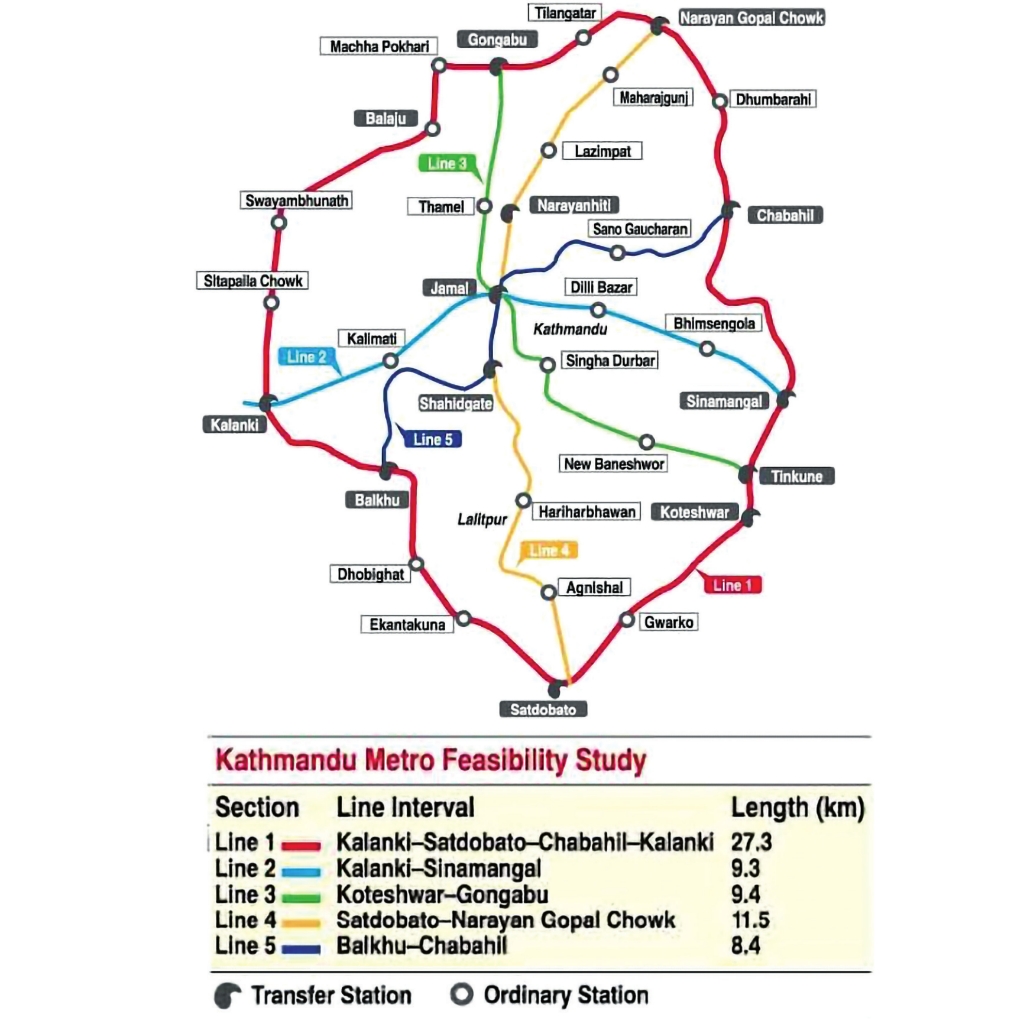

Back in 2011, the government had been looking into the possibility of a metro system in Kathmandu valley and carried out a feasibility study at five different places in core areas. Covering a distance of over 75km and including underground and elevated rail, the planned five lines, one of which was to run along the ring road, would connect most of the valley’s major nodes.

The government was even looking for possible donors and outside support. Fast-forward a decade and the development project is on the backburner. But experts insist increasing congestion in valley roads can be managed only by a mass transport system. Else, it will soon be impossible to commute in Kathmandu.

“If Kathmandu had a metro system, it would mean fewer vehicles on the roads and better connectivity. In places with high population density, the only way to increase mobility is through mass transport options,” says Padma Bahadur Shahi, president, Society of Transport Engineers Nepal. Shahi stresses the need for a Mass Rapid Transit, a mode of urban transport to carry large volumes of passengers quickly, for a thriving economy. He says more movement is vital for economic prosperity, for which fast travel is an imperative.

Kathmandu’s roads are choc-a-bloc with vehicles, garbage and construction materials. Road-expansion hasn’t done much to ease congestion. Without proper public transport, the number of private vehicles plying the roads keeps increasing each year. Nepal Motor Vehicles Sales recorded 21,805 sold units in 2019, way up from 1,400 in 2005. According to a report by the Metropolitan Traffic Police Division, if all vehicles in Kathmandu valley were to be lined up, at 7.2 million feet, it would be longer than the total length of the valley roads (4.5 million feet).

Poor public transport

Aman Chitrakar, senior divisional engineer and spokesperson at the Department of Railways under the Ministry of Physical Infrastructure and Transport, says Kathmandu valley urgently needs a railway system. The government had commissioned the detailed project report (DPR) for it but work has been on halt for some time. Chitrakar says Nepal is still dilly-dallying on the metro when it’s already too late. “Kathmandu’s floating population needs a metro service to ease congestion and provide people with an efficient mode of transport but we are still stuck in studies and preliminary activities,” he says.

Experts say every city needs good public transport—and it’s the government’s duty to ensure that. Nepal has failed to provide this essential service. It’s natural for major cities to face congestion but public transport should largely solve that. But there aren’t fitting government-run services to meet Kathmandu’s growing commuting needs.

The private buses aren’t reliable, as they don’t have fixed schedules and routes. Business-oriented as they are, their poor services (mainly unruly behaviors of drivers and conductors) and overcrowding have compelled many to save up and buy their own bikes or cars.

“With a metro service in the valley, people wouldn’t feel the need to buy vehicles. Kathmandu valley wouldn’t be so chaotic and polluted,” says Shahi, citing the examples of New York and Boston (in the US) and London, Manchester and Birmingham (in the UK) as cities with excellent public transport links. It’s not unusual for people there to ditch personal cars. Chitrakar says there is no alternative to a metro as nothing else can provide the same mass transport service: a standard metro can carry over 30,000 people an hour in a direction.

The many challenges

But there are many constraints to developing a railway service in the valley. The Lalitpur Metropolitan City office apparently opposed the railway plan as the city sees a lot of jatras and authorities weren’t in favor of rail lines running above holy chariots. In areas where underground metro construction isn’t possible, overhead lines will narrow roads. Similarly, heritage sites in Kathmandu valley might obstruct railway paths. Another major challenge will be the valley’s uneven terrains. And then there is also the matter of railways ruining city aesthetics.

Not that having a metro in Kathmandu is an impossible dream. But there must be enough studies and research before committing to such an ambitious and important project. Roshan Devkota, civil engineer, feels Nepal needs to understand its transport requirements and work out a practical and sustainable solution. So far, it hasn’t been able to run effective bus services. Metro, Devkota says, will pose an even bigger challenge.

It’s also not just about building a metro system. The operation phase too should be planned in advance. “Having a metro is not enough, you should also be able to run it effectively. The government should work on making the metro service-oriented rather than not profit-driven,” he says.

Spokesperson Chitrakar emphasizes the need for more investment in public transport. There is no other way out. Madan Bandhu Regmi, urban transport development expert, says the current state of public transport in Kathmandu valley is appalling. First, it is primarily run by private companies, and that shouldn’t be the case. Second, it’s not enough or cheap. Many low-income families still have to think twice before using the bus on a daily basis. According to Regmi, public transport should run on government subsidies and people shouldn’t have to pay much.

Exploring options

“Metro can help improve transport in Kathmandu valley. But it’s not the only option,” says Regmi, explaining that what is really needed is an integrated transport system. When they work in collaboration, various forms of public transport, like buses, tempos, and railways can brilliantly interlink people and places in Kathmandu valley where different areas have different infrastructures and requirements.

The focus should be on developing and using these modes of transport interchangeably. “The metro doesn’t need to connect all places in the valley. Where the metro can’t go, buses and tempos can fill the gaps. We need data and information to determine what is needed where. Then we need to work on developing a system accordingly,” he says.

Shahi says the government doesn’t have a framework of development. Its priority is ever-changing, prone to whims and fancies of those in power. Lack of foresight and unwillingness to conduct in-depth studies have always been the government’s weaknesses and the public ends up paying the price. There have been many studies on the valley’s public transport needs but the government has yet to endorse a single one, says Regmi. He says the way forward is to review all the studies till date to figure out how to create an interconnected multi-modal transport system.

That done, it can break the project down into sizable bits and get donor agencies and development partners involved. “The government takes so much development tax from us, year after year, but it isn’t able to spend. So, it actually has the financial means to build a metro in Nepal. It won’t even need outside help if it’s serious about it,” says Regmi.

Also, confusingly, there are different departments and ministries looking after urban transport in the valley. The Department of Railways, the Department of Roads, the Kathmandu Valley Development Authority and various metropolitan city offices are a few of the government bodies that deal with transport development. This, Regmi says, creates chaos and confusion and delays work.

Without coordination between these agencies, often there is no clarity on who is responsible for what. “We need a separate government department to deal with the various aspects of urban transport. It should be given all the authority required to create a system that works,” he says.

related news

What if… the two-day weekend was made permanent?

May 29, 2022, 2:39 a.m.

What if… the left electoral alliance is revived?

April 1, 2022, 9:22 p.m.

What if… the fast track project was completed on time?

March 18, 2022, 9:32 p.m.

What if… voters got to reject candidates?

Feb. 18, 2022, 9:54 p.m.

What if… we didn’t need the National Assembly?

Feb. 6, 2022, 12:06 a.m.

What if… Kathmandu had more open spaces?

Jan. 22, 2022, 5:34 p.m.

What if… (local) elections cannot be held on time?

Jan. 7, 2022, 6:03 a.m.

What if… the 1923 Nepal-Britain treaty was not signed?

Dec. 25, 2021, 7:37 a.m.

Comments