What if… the 1923 Nepal-Britain treaty was not signed?

It was a watershed moment for the landlocked country precariously sandwiched between two ancient civilizations. Almost a century after the infamous Treaty of Sugauli (1816), Nepal and Great Britain had signed a new one in 1923 as its replacement. It was this new treaty that re-stated Nepal’s sovereignty in the international arena: it showed to the world that the UK, which effectively ran more than half of the world at the time, treated Nepal on an equal footing as a sovereign state.

Say observers, the treaty, now dead, deserves to be more widely discussed. Although the Treaty of Sugauli (1816) and the 1950 Peace and Friendship Treaty with India are endlessly discussed, historians and diplomats alike have only briefly taken up the 1923 treaty, often without highlighting its importance.

The treaty is important as, based on the same, Nepal restated its status as an independent and sovereign country in the international arena. Subsequently, in 1925, the treaty was documented in the League of Nations, the forerunner to the United Nations. It annulled the Sugauli and all previous treaties and allowed Nepal to conduct its foreign policy independently.

More importantly, Nepal used this treaty as a vital document while applying for UN membership in 1949, a year before it signed a peace treaty with independent India. In the application, it was stated that ‘Nepal has for centuries been an independent sovereign state and it has never been conquered, no foreign power has ever occupied the country nor intervened in its internal and external affairs’.

While applying for UN membership, Nepal also presented details of its diplomatic relations with Tibet, France, the US, India, and Burma.

Nepal informed the UN that the 1923 treaty explicitly ‘restated’ the country’s independence and sovereignty. But the application also maintained that, ‘the Government of Nepal has never considered that either the Treaty of Sugauli or any other treaties, agreements or engagements impaired its independence and sovereignty.’

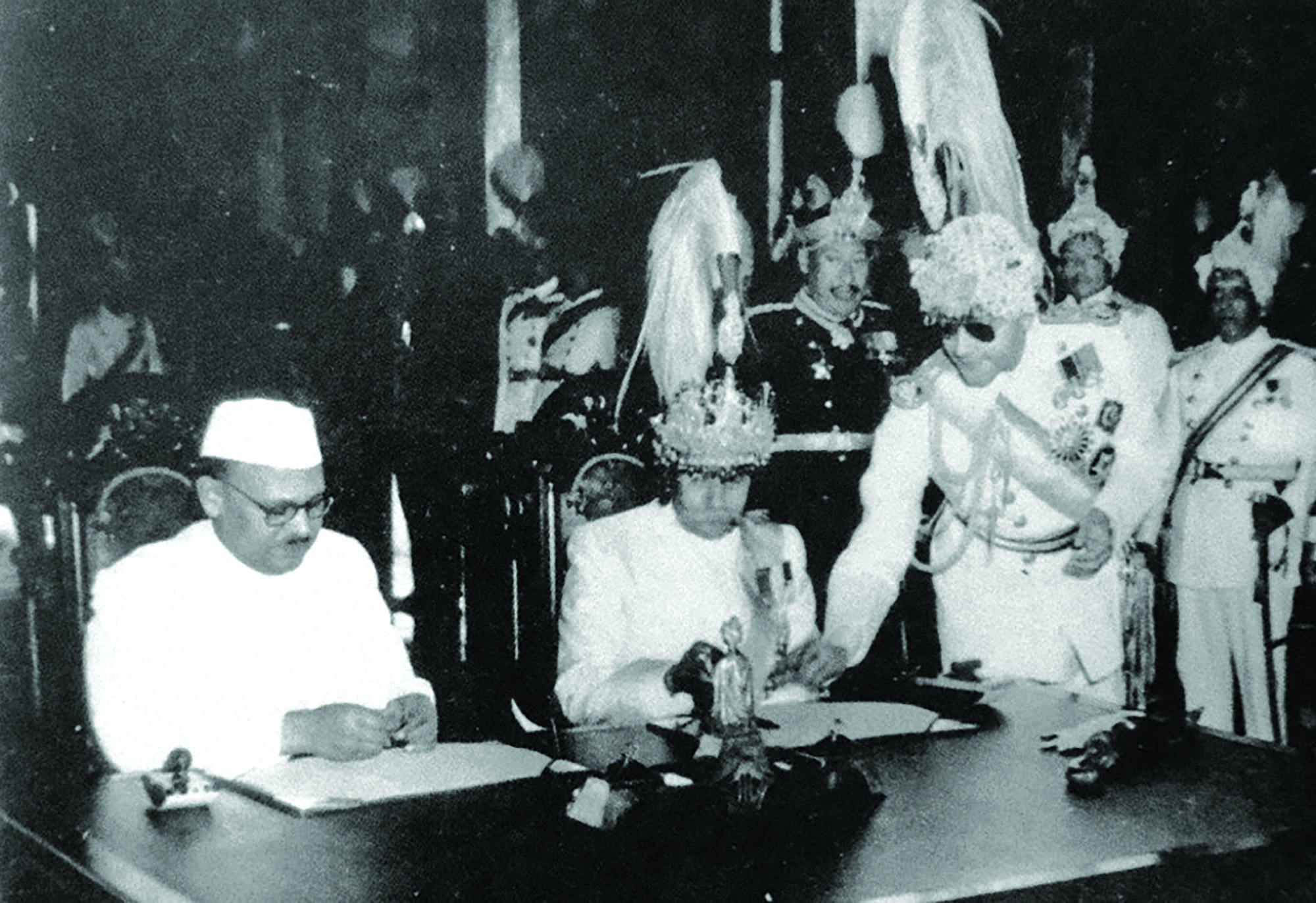

The signing of the India-Nepal Treaty of Peace and Friendship in 1950 by Prime Minister Mohan Shumsher Jung Bahadur Rana and Indian Ambassador Chandreshwar Prasad Narayan Singh.

The signing of the India-Nepal Treaty of Peace and Friendship in 1950 by Prime Minister Mohan Shumsher Jung Bahadur Rana and Indian Ambassador Chandreshwar Prasad Narayan Singh.

The treaty upgraded Nepal’s diplomatic status. With its signing, the status of the British representative in Kathmandu was upgraded to the level of Ambassador, which helped lift Nepal’s profile in the international arena.

Professor Rajkumar Pokhrel, head of Department of History, Tribhuvan University, says had the 1923 treaty not been signed, the tripartite agreement between India, Nepal, and the UK in 1947 may not have been possible. Similarly, there would have been no 1950 treaty between Nepal and independent India.

Nepal certainly has many reservations about the 1950 treaty and has been pushing for its amendment. But it was 1923 that laid the foundation for the 1950 treaty. The provisions of the two treaties are almost identical.

Historian Sagar SJB Rana says the similar provisions of the two treaties surprised him. Except for a provision which mentions equal treatment of each others’ citizens, other points are the same. So the basis of the 1950 treaty is clearly the 1923 treaty, Rana says.

According to historians, then Prime Minister Chandra Shumsher worked hard to get the British government to sign the treaty. Within a few days of becoming prime minister in 1901, Chandra Shumsher had dispatched a letter to British India seeking closer ties, giving a clear message that Nepal and Britain India are two sovereign nations and should be treated accordingly, says historian Rana. After becoming prime minister, Chandra Shumsher started to assert his position as the head of the government of an independent country while dealing with British India.

Chandra Shumsher JBR, Prime Minister (1901-1929).

In a recently published book titled Gaida’s Dance with Tiger and Dragon, political analyst Achyut Wagle writes of how the British government in 1920 accorded Chandra Shumsher with the honor of ‘His Highness’, which was “an implicit recognition of him as a prime minister of sovereign Nepal.”

Historian Rana says a Nepali ruler had never before gained such respect, and this translated into respect for his country’s status. Chandra Shumsher was later decorated with different British titles and honors. Soon after the treaty, the UK started addressing Nepal’s King as ‘His Majesty’, a title comparable to the one accorded to the British monarch. After that, other countries also started treating and respecting Nepal as an independent country.

At the same time, the British were thinking of rewarding Nepal for its contribution to the First World War. Nepal had contributed hundreds of thousands of troops and resources for the British war efforts, and the subservience to the British Empire helped Nepal be recognized as an independent state.

As a mark of gratitude for the Rana regime’s war-support, writes Wagle in the book, the British government in India, in March 1920, announced a support package of a million Indian rupees grant an annum and a one-time purse of Rs 2.1 million for Nepal.

All these developments show that the British government was gradually starting to recognize Nepal as an independent and sovereign country. As Chandra Shumsher was determined to sign a new treaty, preparations were taking place at the government level. When the Prince of Wales visited Kathmandu in 1921, Chandra Shumsher renewed his proposal for a new treaty. In his book, ‘Nepal Strategy for Survival’, Leo E. Rose writes of how the proposal met with a sympathetic response, and negotiations began in Kathmandu shortly thereafter.

Also read: What if… there was a referendum on Hindu state?

“Nevertheless, it took nearly two years of leisurely negotiations to produce a draft agreement for, as the British envoy noted, ‘there were… certain points both of principle and detail involved which required very careful consideration, and the weighing of literally every single word,’” Rose writes.

The treaty was finalized in 1923 after much consideration and signed in Singha Durbar the same year, ensuring that ‘Nepal and Britain will forever maintain peace and mutual friendship and respect each other's internal and external independence,’ among other provisions.

Following its signing, peace and tranquility prevailed at the border, says Dr Pokhrel, the historian, as the British were honest about its implementation.

Yet the 1923 treaty has its critics too. Writes Retd Major General of Nepal Army Purna Chandra Silwal Silwal in his book Nepal’s Instability Conundrum, “Although the treaty recognized Nepal’s independence for the first time in its history, the sovereign rights to import arms and ammunition from other countries were not fully respected. If the British government so desired, the provision would have been revoked. Hence, the British intention was to make Nepal submit.”

Historians say whatever the motivations for the 1923 treaty, on either side, Nepal probably would not be an independent state today without it. And Chandra Shumsher will forever get the credit for it.

Tika Dhakal

The 1923 treaty gave Nepal a unique identity

Named the “Treaty between the United Kingdom and Nepal”, its significance remains in its unequivocal recognition of Nepal’s external and internal sovereignty and independence by the United Kingdom, the world’s greatest power of the time. This treaty may be called foundational in that it gave Nepal the ability and basis to conduct independent foreign policy and bilateral relations with other countries. It was the only treaty of Nepal to be recorded in the League of Nations.

In the academic discourse predominantly focusing on the Treaty of Sugauli (1816) and the Nepal-India Treaty of Peace and Friendship (1950), it is worth remembering that several aspects of the 1923 treaty retain their importance. Today, the legacy of this treaty has been carried forward by the two treaties Nepal signed in 1950, with India and the United Kingdom respectively.

The substance of this treaty may be further interpreted in terms of the evolution of the concept of state in Nepal, which in the pre-treaty political context used to be associated with land being under the ruler’s possession. This notion of ownership based on Hindu traditions provided the ruler with inherent powers to collect taxes, exercise control and maintain order within the land possessed. The duality and interplay between the ruler and the people living in the land formed the essence of the concept of state, not only in Nepal but in the entirety of South Asia. This was so until the Westphalian concept of sovereignty arrived via imperial Britain.

Now enshrined in the UN Charter and universally accepted principle of the value-based international system, the idea of Westphalian state has transformed into the principle of equal sovereignty of states irrespective of the size of their geography, population and military. The modern state is therefore the reflection of human individuality. In addition to population, geography and legitimate government in internal contexts, sovereignty of a modern state is established externally on the basis of recognition it gets from the community of states. Although in veiled terminologies, literature on statecraft had formulated this element of sovereignty several centuries ago, as noted in Kautilya’s Arthashastra, which says that a state for its own protection would need friends, and friends may be gained or abandoned through treaties.

The 1923 treaty has also been criticized for perpetuating Nepal’s dependence and is termed unequal as the signatory on the Nepali side was Prime Minister Chandra Shumsher while signing it on the behalf of the UK was ambassador Willian Travers O’connor. But we have to see the larger picture leaving aside our ‘presentist’ biases. The treaty is certainly an important historical event that gave Nepal a unique identity as a modern state.

Dhakal is information and communication expert advising President Bidya Devi Bhandari and a PhD candidate in political science at TU

related news

What if… the two-day weekend was made permanent?

May 29, 2022, 2:39 a.m.

What if… the left electoral alliance is revived?

April 1, 2022, 9:22 p.m.

What if… the fast track project was completed on time?

March 18, 2022, 9:32 p.m.

What if… Kathmandu valley had a metro service?

March 5, 2022, 5:34 p.m.

What if… voters got to reject candidates?

Feb. 18, 2022, 9:54 p.m.

What if… we didn’t need the National Assembly?

Feb. 6, 2022, 12:06 a.m.

What if… Kathmandu had more open spaces?

Jan. 22, 2022, 5:34 p.m.

What if… (local) elections cannot be held on time?

Jan. 7, 2022, 6:03 a.m.

Comments