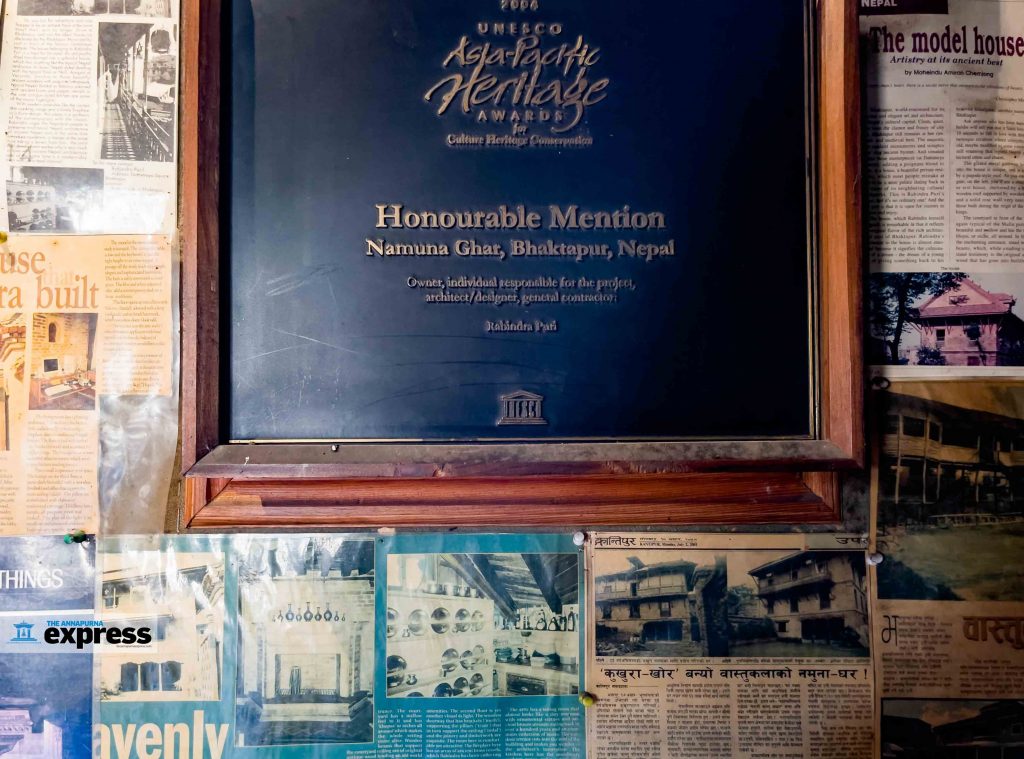

A closer look at Namuna Ghar (Photo Feature)

The Namuna Ghar in Datattraya, Bhaktapur, is a special heritage that reflects Nepal’s glorious medieval art, architecture, and history. The house was initially discovered to be over 150 years old before the restoration process by Rabindra Puri in 1999. It was being used as a chicken coop, a shame for all the potential it held.  This house was redesigned and rebuilt, now featuring beautiful attributes that graced traditional Nepali architecture. It went on to win the prestigious UNESCO Asia-Pacific Awards for Cultural Heritage Conservation in 2004.

This house was redesigned and rebuilt, now featuring beautiful attributes that graced traditional Nepali architecture. It went on to win the prestigious UNESCO Asia-Pacific Awards for Cultural Heritage Conservation in 2004.

Even prior to attaining global recognition, the building was already regarded to be Namuna Ghar (translates to mean ‘model house’) by Bhaktapur Municipality, which is how the building got its name.  “When I first joined the heritage conservation field, I was called insane for passing up a comfortable life and career in Europe and choosing a zero-income sector,” says Puri.

“When I first joined the heritage conservation field, I was called insane for passing up a comfortable life and career in Europe and choosing a zero-income sector,” says Puri.  About 60 percent of this building required new construction, with the remainder achieving satisfactory results through retrofitting. Original structural components were carefully removed and reused wherever possible. This restoration project was completed in roughly a year and a half.

About 60 percent of this building required new construction, with the remainder achieving satisfactory results through retrofitting. Original structural components were carefully removed and reused wherever possible. This restoration project was completed in roughly a year and a half.

Quickly thereafter, the home gained traction and received unexpected appreciation and recognition. Items that highlight Nepali culture and tradition are on display at Namuna Ghar. The main objective for restoring and promoting Namuna Ghar with this approach is to inspire Nepali people to appreciate and conserve their rich and beautiful heritage.  “I also started a homestay at the Namuna Ghar, and it was from here, the concept of bed and breakfast took off in Nepal,” Puri adds.

“I also started a homestay at the Namuna Ghar, and it was from here, the concept of bed and breakfast took off in Nepal,” Puri adds.

Pradeep Gyawali: Government has lost international credibility

As the CPN (Maoist Center) supported Nepali Congress over CPN-UML in the presidential poll, UML left the government and Congress joined the Pushpa Kamal Dahal-led cabinet. Pratik Ghimire of ApEx talked to UML leader Pradeep Gyawali about the evolving political situation after the poll.

How do you see the current coalition led by Dahal? Will it sustain for five years?

This coalition is unnatural to the core. The coalition partners are together only for petty interests. If they were sensitive toward national interest, why would they drift apart after the presidential poll? And there is no chance of this coalition lasting five years. It will break apart soon and the erstwhile partners will start fighting for their own interests.

Why do you think Dahal betrayed UML?

Consider these three factors. The first one is the fact that Dahal is well-known for his opportunist and volatile behavior. He has done this to every political party and no one knows this better than UML. Yet, we gave him the benefit of the doubt. The second thing is his fear psychosis. He thought his interest couldn’t be served while being with UML as we had a mechanism where the government had to come clean on its wrong moves at coalition partner meetings.

We talked about service delivery, good governance and national interest, which Dahal didn’t want to follow. The involvement of international powers is the third factor. We saw the officials of foreign nations manipulating the government to serve their national interests. If we were in the government, we would not have let such things happen. As for Dahal, he wanted to serve international interests.

How will UML play the role of the main opposition?

As the main opposition, we will have two major roles to play. For us, this is the right time to reorganize the party. For a long time, we were in the government and unable to build the party properly. We will utilize this time to rebuild the party from the grassroots. We have already started campaigns to make the UML a strong national force. We will raise people’s voices from the parliament and from the streets, if necessary. We will not let the public suffer. We will do everything to make the government accountable.

Is there any possibility of an NC-UML coalition?

After the Nov 20 poll results came out, the Congress and the UML should have collaborated to form a government in the national interest because the people had given us—not the small parties—the mandate. We formally proposed the Congress for a coalition, but they ignored us. Amid public frustration, such a government had become necessary for democracy and stability of the political system. But then the Congress had other plans. The scenario has changed and there’s no chance of an NC-UML coalition, for now. But if the Congress wants to form a coalition with us in the national interest, we are open for discussion.

As a former foreign minister, what do you have to say on this government’s foreign policy?

I don’t have much expectations from this government. I hope that they don’t make things worse. None of the neighbors trusts us. We have lost international credibility. We were not invited to the Raisina Dialogue. We were invited to the Boao Forum, but the prime minister shunned it. We are in a difficult situation. Even with the US, the Maoist party, as a partner in the then coalition government, made the MCC Compact controversial by signing on it, then protesting against it and finally playing a role in its endorsement through the parliament. Why would the international community believe us?

And recently, the way Dahal canceled the visit of the incumbent foreign minister to the Human Rights Council’s conference and sent an unauthorized person to the event has made our foreign policy and presence immature. That conference was very important for us as we could have shared so many things with the international community regarding our progress and achievements on the human rights front.

Economist Wagle ditches Congress

Swarnim Wagle, a Nepali Congress leader and renowned economist, has left the party. Wagle announced his separation from the party through a social media post, creating ripples in the digital forum where both his admirers and critics traded blows over his move. Citing the main reason behind the loss of his love for the party, Wagle wrote: “I have decided to part ways with the Nepali Congress, with which I had been associated since the mid-1980s.”

“Congress has now turned into an incompetent gang of family members,” the youth leader wrote in his astute observation, noting that he had played a significant role in improving the Congress’ economic policies and planning in various capacities over the decades. “During my indirect association with the party spanning 30 years and direct contribution of 10 years, I conducted several intellectual-theoretical discussions and training. At the same time, I played a role in expanding international legitimacy for the party,” he pointed out.

Wagle ‘felt proud’ to note that both Sushil Koirala and Sher Bahadur Deuba had appointed him at the National Planning Commission. Giving himself a pat on his back for a job well done, Wagle noted that he had been able to fulfill the responsibilities entrusted to him and enhance Nepal’s prestige.

Elaborating on his future plans, Wagle said he will be active in a new public role with the beginning of the new year, carrying forward the agendas of democracy and economic progress on the foundation of good governance.

New bill stirs telecom sector

A proposed amendment to the Telecommunications Act allowing the government to tap phone calls without prior court approval has raised a debate over the right to privacy. But two more provisions in the draft amendment bill have somewhat gone under the radar, and they could have a profound impact on the country’s telecom sector. If passed as it is, it will also dent significant revenue to the government.

First is the removal of the provision where the assets of telecom companies with foreign investment of over 50 percent automatically come under government control after the expiry of their 25-year license duration.

Second is slashing of the licensing fees, royalties, and other charges. The draft of the Bill to Amend and Unify the Laws Related to Telecommunications, prepared by the Ministry of Communications and Information Technology, has already received an ‘in principle’ approval from the Cabinet, according to Netra Prasad Subedi, spokesperson at the ministry.

According to industry insiders, some major private players in the telecom industry are set to benefit from the new provisions. The provisions related to the license fee and renewal fee in the draft bill will provide big relief to telecom companies struggling to pay government dues as well as new ones planning to enter the telecom sector.

The draft bill has proposed cutting down the fees, royalties, and other charges that the government takes from telecom companies. At present, the fee for obtaining the license for a telecom company stands at Rs 350m. The proposed bill has reduced the fee for an integrated license to Rs 10m. It has also proposed to lower license renewal fees.

As per the existing law, a new telecom company must first renew its license after 10 years and then after every five years by paying a fee of Rs 20bn. In the draft of the proposed bill, the license renewal fee has been revised to Rs 10m or 10 percent of the company’s total income, whichever is higher for every year of the first five years.  Similarly, a fee equal to Rs 250m or 10 percent of the total income of the company, whichever is higher, will have to be paid every year to the government from five to 10 years after obtaining the permit. After 10 years, the telecom company has to pay Rs 2bn or 10 percent of the total income earned that year, whichever is higher. Telecom experts say the new renewal fee proposed in the draft bill will make no difference to existing players—Nepal Telecom and Ncell.

Similarly, a fee equal to Rs 250m or 10 percent of the total income of the company, whichever is higher, will have to be paid every year to the government from five to 10 years after obtaining the permit. After 10 years, the telecom company has to pay Rs 2bn or 10 percent of the total income earned that year, whichever is higher. Telecom experts say the new renewal fee proposed in the draft bill will make no difference to existing players—Nepal Telecom and Ncell.

As both companies’ annual income is around Rs 40bn, they have to pay 10 percent as license fee, which is around Rs 4bn every year. This is in line with the current provision that Rs 20bn is to be paid in five years. However, the government will lose huge revenue from the companies that have been currently holding licenses but not doing substantial business. The state will lose Rs 347.5m as license fees from a telecom company from now onwards.

Similarly, the state would have received Rs 20.13bn from each telecom company in the first 10 years and the same amount in every five years for the next 15 years. Similarly, Ncell Limited, a subsidiary of Malaysian multinational telecommunication conglomerate, Axiata Group Berhad, could also be a direct beneficiary of these proposed amendments. Ncell’s license was issued on 1 Sept 2004 in the name of Spice Nepal, and it will expire on 1 Sept 2029. According to the existing law, the company is set to come under government ownership after six and a half years.

However, Ncell has been lobbying for amendment to the existing law so that it could renew its license even after its expiry. As per the draft bill, companies already holding licenses for cellular mobile, basic telecommunications, and rural telecommunication services can apply for integrated licenses within one year of the implementation of the amended Act.

Subedi, the spokesperson at the Ministry of Communications and Information Technology, says though the government has given ‘in principle’ approval to the draft bill, there is still room for further improvement. He adds that the provision related to the government taking control of the assets held by telecom companies with foreign investment can be further discussed and improved upon.

The draft bill also proposes that telecom companies can operate for as long as the frequency is available, which overrides the existing law requiring telecom firms to get frequency separately after acquiring the operating license. So, any company capable of getting frequency can obtain a license to operate telecommunication services.

Subedi says the draft bill has proposed charging royalties and other fees based on the company’s income. Rather than reducing the fees, he explains the proposed provision is aimed at charging the telecom companies based on their income.

Dhawal Shamsher Rana: Ex-king is worried with the situation of country

Rastriya Prajatantra Party (RPP) pulled out its support from the Maoist-led government as soon as Prime Minister Pushpa Kamal Dahal decided to change the coalition. The pro-Hindu and pro-unitary party seemed out of place when it was in the government. Now, in the opposition role, the party is planning to raise its demands for reinstatement of Hindu state, monarchy and unitary government both in Parliament and from streets. A party delegation even met former king Gyanendra Shah recently. In this context, Pratik Ghimire of ApEx talked to RPP lawmaker and leader Dhawal Shamsher Rana.

Why did your party leave the government?

We didn’t want to involve our party in the dirty politics of Dahal and other coalition partners. It had not even been 45 days since we joined the government, and the prime minister collaborated with the Nepali Congress to fulfill his personal interests. We didn’t like this attitude. When we were in the government, our goal was to make it more dynamic and public-centric. But we later realized that Dahal was not interested in it.

What kind of role will RPP play as an opposition?

We will support and protest the government by analyzing the work it does. We don’t want to let the people suffer for no reason. The RPP will protest from the House as well as on the streets.

What kind of protest is the party planning to stage?

We will hit the streets with the support of the public who are against federalism and the republic system. We will demand for a constitutional monarchy and Hindu state.

Do you think people will trust and support your movement?

They will for sure. Is there any significant progress these republicans have done for the public to support them? No. The public is frustrated, and we will help bring back the leadership and guardianship of the king.

What did you discuss with the former king?

It was a good conversation. We discussed contemporary political and social issues. He is frustrated about the condition of Nepalis. As we are supporting him being the head of our proposed constitutional monarchy, we discussed how we can help and support each other.

Teknath Rijal: Seek SAARC help on Bhutanese refugee issue

During the early 90s, tens of thousands of Nepali-speaking Bhutanese citizens fled or were deported from the country. They would eventually end up in eastern Nepal via India, and reside there as refugees. Over the years, a large number of refugees have gone on to settle in the US, Australia and various European countries as part of the UN third-country resettlement program. A small number of Bhutanese refugees are still based in Nepal, and they wish to be repatriated back to their homeland. Pratik Ghimire talked to Teknath Rijal, a refugee leader and human rights activist, about the present situation of Bhutanese refugees in Nepal.

How did the Bhutanese refugee crisis begin?

South Bhutanese were protesting against the government, demanding democracy and human rights for a long time. In the past, ordinary people weren’t supposed to write history; it was against the law. It is said that Bhutanese refugee crisis began in 1991, when Bhutan started expelling people of Nepali origin. But the crisis precipitated way before that. Even history says how the aristocrats have oppressed and even brutally murdered Nepali speaking Bhutanese.

What is the present situation of Bhutanese refugees?

Refugees were taken to third countries for resettlement and this somewhat addressed a problem. But there are still many Bhutanese refugees, either awaiting resettlement or repatriation. India has a great influence on Bhutan when it comes to resolving the issue relating to repatriation of refugees, but the Indian government hasn’t been helpful. Different media have been talking about this but recently South Asia Watch has come up with an intensive report regarding the plight of Bhutanese refugees. But India has been abstaining itself from involving in this issue saying it is the matter between Nepal and Bhutan.

How many refugees are there in Nepal?

I think there are around 8,000 of them, spread in different parts of Nepal. Some of them have verification cards of refugees and there are those who have no such identification. After the UNHCR left the camp, there were still around 400 refugees who were unverified. In 2011, Nepal stopped registration of Bhutanese refugees. But the problem is Nepali-speaking Bhutanese people have not stopped entering Nepal, and they have no access to any facilities. Their stories are not being told by the media. They are living as stateless people. According to my estimates, there are more than 1,000 such refugees living in the various parts of Nepal.

How’s the condition of Bhutanese refugees who have resettled in third countries?

Some Bhutanese were sent to third countries but it seems like they aren’t all having a good life there as well. Many of them are suffering. Bhutanese refugees settled in third countries are home-sick and there are reports of some committing suicide, because they miss their home country, their neighbors and their near and dear ones. Members of some families have been scattered and have no way to reunite.

What do you think is the way out?

There have been several bilateral talks between Nepal and Bhutan, where Bhutan has acknowledged that 90 percent of the refugees are Bhutanese. Nepal says Bhutan is avoiding further discussion about refugees. In this situation, Nepal should be seeking help from India or other SAARC member states. There are many agendas that need to be explored on many aspects. India should be brought on board and made to comprehend the gravity of the issue. The tyranny of the king toward his own citizens must be revealed. I would also request international organizations to be a part of this refugee issue and help the Bhutanese families, protect their human rights and stop the atrocities of Bhutanese government. My special request is to Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi who can play a vital role to settle this issue.

Suman Adhikari: No hope from new amendment bill

Amid protests from victims of the decade-long insurgency, Minister for Communications and Information Technology Rekha Sharma, on behalf of Prime Minister and Law Minister Pushpa Kamal Dahal, tabled a Bill to amend the Enforced Disappearances Enquiry, Truth and Reconciliation Commission Act in the House of Representatives. Pratik Ghimire of ApEx talked to Suman Adhikari, a conflict victim, to get his views on the Bill.

What’s your take on the transitional justice amendment Bill?

This Bill is just a dust in the eyes of the public. If successive governments had cared about us, they could have addressed our demands very early. The incumbent government has shown some interest to amend the Bill under much pressure. Concerned authorities drafted this instrument to serve their interests, so it is full of loopholes. For one, it has not incorporated the sentiments and demands of the conflict victims’ community.

What were your demands?

The Bill states that the tenure of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission shall be of two years. But it is mum on the organizational structure of the commission, its human resource and infrastructural requirements and how it will work with different tiers of the government. The Bill is mum on the jurisdiction of the commission. Also, the tenure of the commission is not the only issue. Who all are appointed at the commission and how effectively it works; these are crucial issues. If appointments are made on the basis of recommendation from political parties, victims like us will have to suffer.

Most importantly, we wanted this draft prepared after consulting us (the victims) and incorporating our recommendations as nobody knows the pain better than us. But the drafters of the Bill never sought our suggestions. It always appears that they are doing it all for themselves, not for us. The time has also come to review the transitional justice system.

What’s your comment on political parties’ stances?

No major party seems committed to this matter. The Nepali Congress never speaks on this topic. I was amazed to find that not a single lawmaker from the CPN-UML spoke while the Bill was being presented in the parliament. Rastriya Prajatantra Party’s Gyanendra Shahi commented on the Bill but we don’t know whether it was his personal opinion or his patry’s. Even the Rastriya Swatantra Party was silent. We had not expected this. Only Nepal Majdoor Kisan Party and Rastriya Janamorcha took a stance in our favor.

What about the international community?

They too are silent. The embassies in Nepal used to talk on this matter quite frequently a few years back. But these days, it’s rare to find them talking .

What next for the conflict victim community?

Even in the victim community, there is no single voice. Many victims are still supporting the steps of the political parties, while many others don’t care. Others like me are raising our voices constantly, we will continue to do so peacefully. We need the rule of law in the nation and justice. That’s all.

Many ministerial aspirants inside Congress

The Nepali Congress has officially decided to join the coalition government led by CPN (Maoist Center). The two parties, which had forged an alliance to contest the general election in November last year, had fallen out over a power-sharing dispute after the polls and gone separate ways.

The Maoist went on to form a government with the primary backing of the CPN-UML on 25 Dec 2022, while the NC helmed the opposition. But the Maoist-UML coalition broke up within two months, once again bringing the Maoist and NC together. With this, a race has begun inside the NC for ministerial posts.

A party meeting on Sunday set criteria for ministerial candidates to represent the party in the Pushpa Kamal Dahal-led government. Congress Spokesperson Prakash Sharan Mahat said candidates would be selected on the basis of academic qualifications, contribution to the party, inclusivity, and balance of power at the provincial level.

President Sher Bahadur Deuba will pick the candidates on the basis of policy-decision taken by the party, he added. Prime Minister Dahal is set to give full shape to his Cabinet after taking the vote of confidence in Parliament on Monday. The NC has demanded eight ministries in the Dahal government in order to accommodate the leaders from the camps led by Shekhar Koirala, Krishna Prasad Situala, and Prakash Man Singh. He must also make room for some leaders from President Ram Chandra Poudel-led faction as well as his own supporters.

One Congress leader told ApEx that Deuba has a tough job of satisfying everyone inside the party, including those from the rival factions. Members of the chief rival camp, led by Koirala, had backed Deuba’s decision to give the trust vote to Dahal back in January, and now they expect the party leadership to reciprocate the gesture by offering them positions in the government. It is almost certain that the NC will get two vital ministries—finance and foreign affairs.

It is said Deuba’s spouse Arzu Deuba has shown interest to lead the foreign ministry, while Mahat is trying to land the finance portfolio. Senior leader Singh, who fought for the party presidency and later supported Deuba, is said to be making a bid for deputy prime ministership to lead the NC in the government.