Know your new president

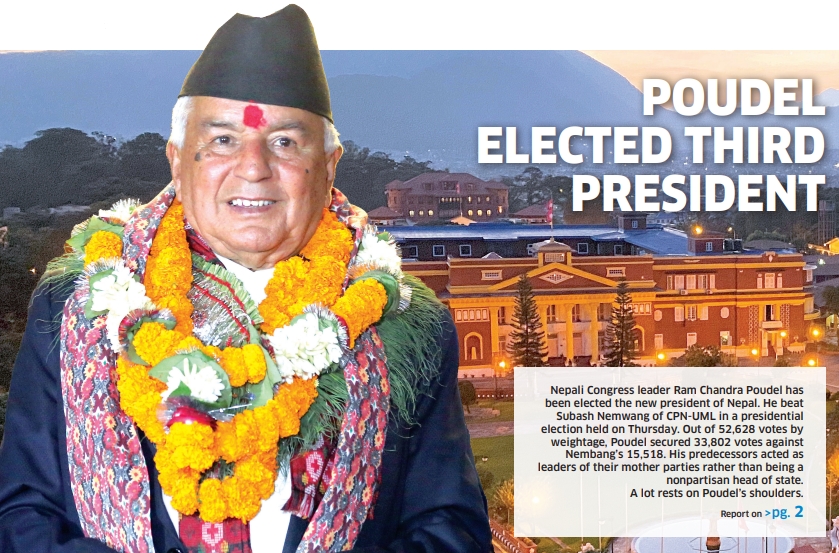

Born to Durga Prasad and Hrishimaya Poudel on 14 Oct 1944 in Tanahun, Ram Chandra Paudel completed his schooling from Nandiratri Secondary School, Naxal, Kathmandu in 1963. He has a master’s degree in arts from Tribhuvan University. He is married to Sabita Poudel and they have four daughters and a son.

Paudel was inspired to join the democratic movement at the age of 16 after the dissolution of the popularly elected parliament and imprisonment of leaders including then prime minister BP Koirala in Dec 1960. He was associated with the Armed Insurrection Movement for the restoration of democracy, and initiated the students’ movement in 1962. Paudel was given a role in organizing Nepal Student Union in 1970 and got elected as a senior member of the committee of the union. His national political career began in 1977 after he was elected a member of the Nepali Congress Tanahun District Committee. Soon he rose the ranks and became the vice-president and president of the district committee.

In 1983, he was made the coordinator of the Nepali Congress’s Central Publicity Committee. Paudel went on to become a member of the Central Committee member of the party and was made the chief of its central level Publicity Bureau in 1987. In the general election of 1991, he was elected a Member of Parliament from Tanahun-1. He served as the minister for local development and agriculture for around three years. Poudel was reelected from Tanahun-2 In 1994.

This time he was elected the speaker of the House of Representatives (lower house) and served until 1998. He also served as Minister for Home and Deputy Prime Minister from 1999 to 2002. In 2006, after the Maoists joined peaceful politics, Paudel was appointed the coordinator of the Peace Secretariat that included representatives from top political parties. He was appointed Minister for Peace and Reconstruction in 2007.

In between, he was made the General Secretary of the Nepali Congress’ Central Committee and was later promoted to Vice-president of the same committee in 2007. In 2008, he was elected as a member of the first Constituent Assembly from Tanahun-2 and was elected as Parliamentary Party Leader of Nepali Congress.

After Pushpa Kamal Dahal resigned from the post of prime minister in 2009, Poudel contested for the post of premier for 13 times, but failed to pass the threshold. Poudel was elected the vice-president of Nepali Congress from the 12th general convention of the party. He served as the acting president of the party after the demise of then party president Sushil Koirala.

Paudel was elected as a Member of Constituent Assembly from Tanahun-2 in 2013 and Member of Parliament in 2022. He was defeated in the parliamentary election in 2017 by CPN-UML candidate Krishna Kumar Shrestha.

In his political career, Paudel was detained and jailed several times. The longest time he spent in jail was from 1971 to 1975 for being involved in various activities of the student movement, soon after the release of deposed Prime Minister BP Koirala from Sundarijal Jail. He was charged for taking part in a protest program against the Ramailo Jhoda scandal (Morang). In this period, BP Koirala met him at Central Jail and told him not to be distracted, which inspired Paudel to lead the democratic movement, he often says. It was there that Paudel met Koirala for the first time.

He has also published a few books: ‘A Brief history of Nepali Congress’, ‘Democratic Socialism A Study’, ‘What does the Nepali Congress say?’ and ‘Agrarian Revolution and Socialism’ among others. Within the party, Paudel is known as a coordinator and moderate leader. He also played a moderate role in the historic negotiations and consensus to bring the Maoists into mainstream politics and is also known as the drafters of the 12 points Consensus and Comprehensive Peace Agreement.

What should be the role of the new president?

Veteran Nepali Congress leader Ram Chandra Poudel has been elected as the new president of Nepal. He is the third elected head of state after Nepal abolished monarchy and became a republic in 2008. Poudel succeeds Bidya Devi Bhadari who served two terms after Dr Ram Baran Yadav, the first president. Although the post of the president is ceremonial in nature, the past two presidents have courted controversies for acting in favor of their political parties, instead of being a nonpartisan head of state and protector of the constitution. In this context, Pratik Ghimire of ApEx talked to some experts and politicians to solicit their views on what role the new president should play.

Binoj Basnyat, Security analyst

With the indications of current political turmoil and desperations of parties over the presidential post, it has been proved how important this post is despite being a ceremonial one. The President should safeguard national interest and unity. The predecessors, being active members of political parties, took controversial steps. This time, too, we have a senior political leader as President. To avoid controversies, he should stay away from party politics. As the supreme commander-in-chief of Nepal Army, the President has a role to play during national crises. He should also play a role to strengthen our diplomacy, and advise the government to revive our failing economy.

Bipin Adhikari, Constitutional expert

Our constitution has mandated dozens of works and responsibilities to the President. The new President should fulfill his constitutional roles while following the protocols. As the roles of Prime Minister and President are interrelated, they should complement each other. The President has no power to go against the government but in case of a minority government, he can use his conscience to guide the country. Even when the government issues ordinances, the President should have the gumption to suggest the PM to wait for the parliamentary session and follow due process. If the president truly abides by the Constitution, he can do no wrong. In case of a difference of opinions on matters of national interest between the President and the PM, it should be made public to facilitate a healthy debate.

Gopal Khanal, Politician, CPN-UML

As the President is the custodian of the Constitution and the guardian of the nation, he should always work for the greater good of the people. Sometimes the executive tries to misuse power, the President should prevent such a situation. The head of state should maintain the check and balance of powers. In Nepal, President has no executive powers, but that doesn't mean the former should act like a rubber stamp in service of the PM. I have mixed feelings regarding past Presidents and their tenures. They came through political struggles and deserved the post more than anyone else, yet, political parties dragged them to controversies. The new President should always analyze what the political parties expect from him, while upholding national interest, unity and integrity.

Shankar Tiwari, Analyst

The new President should avoid controversies and also correct the presidential course. He should work within the constitutional framework. The PM and the President should meet at least once a week to discuss national and geopolitical affairs; there should not be any communication gap between them. Lastly, the motorcade of the president must not hamper the public. The new president should think of other alternatives.

Bishnu Dahal, Political analyst

As both presidential candidates had served as the speaker of the House, they know how to be above their political parties and how to act in accordance with the Constitution. As for Ram Chandra Paudel, he has a democratic background, and as a senior leader of Nepali Congress, he knows how to follow democratic rules. So, I think, he will disassociate himself from the party and follow the Constitution. He must help the government to make Nepal a sound nation geopolitically. The outgoing president has left behind a series of controversial decisions for the new one to learn from.

Bishnu Bhattarai, Senior advocate

The President should promote national unity. The political parties could not arrive at a consensus on the head of the state. This means the President will be a partisan figure and such a figure cannot be the symbol of national unity. No elected political figure shall ever hold the presidency because s/he will always be a divisive figure.

Ananta Raj Luitel, Constitutional law expert

According to the Constitution of Nepal, the President is a nominal head of the state. He/She cannot take any discretionary decision but needs to act on the basis of the recommendation of the Council of Ministers, the Constitutional Council and the Judicial Council or other relevant recommending authority. The President should stay within these bounds.

BIMSTEC passes key instruments as SAARC stalls

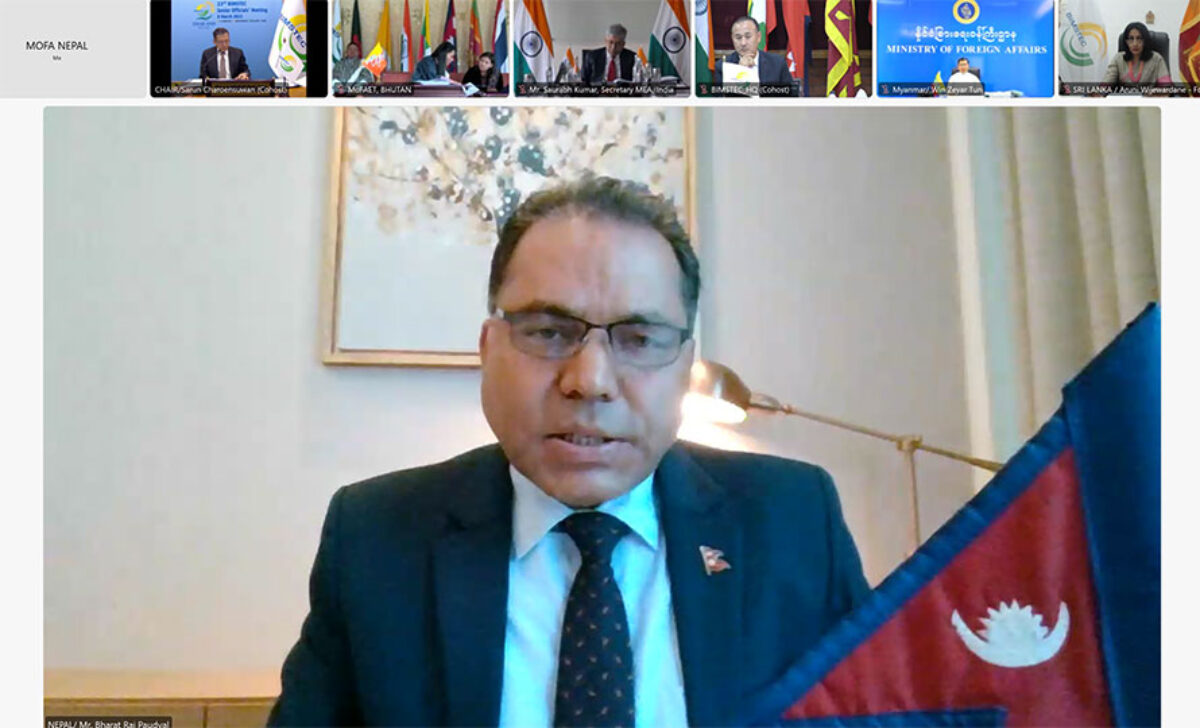

The 19th ministerial meeting of the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC) on Thursday passed some key instruments, giving a fresh impetus to the regional body.

The ministerial meeting endorsed important instruments including the BIMSTEC Bangkok Vision 2030, agreement on maritime transport cooperation, rules of procedures for several mechanisms, terms of reference for Eminent Persons’ Group, inclusion of blue economy, mountain economy and poverty alleviation under the purview of reconstituted sectors. The meeting was held virtually in Bangkok, and Nepali delegation was led by Foreign Secretary Bharat Raj Paudyal.

Addressing the meeting, Paudyal called for meaningful regional cooperation to deal with the defining challenges of our times such as climate change, energy crisis, food insecurity and the large-scale pandemic. Recalling the fourth BIMSTEC Summit held in Kathmandu in 2018, which aptly prioritized institution building of BIMSTEC, Paudyal underlined the need for conscious, credible, and concerted actions to achieve a more resilient, prosperous, and sustainable Bay of Bengal region.

Paudyal also updated on the progress achieved in the Sector of ‘People-to-People Contact’ that is being led by Nepal. He also informed the meeting on the efforts made toward creating platforms for people-to-people engagements in the BIMSTEC region, such as the Parliamentarians and Speakers forum, and separate forums of entrepreneurs, universities, and researchers, etc.

Over the past few years, BIMSTEC has gathered momentum, while another regional body, South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), remains stalled since 2016 over the India-Pakistan dispute.

Though Nepal is taking initiative to revitalize the SAARC process, other member countries, particularly India, are not serious about it. Preparations are underway to hold the sixth BIMSTEC summit but the future of SAARC is uncertain.

Loose lips sink ships

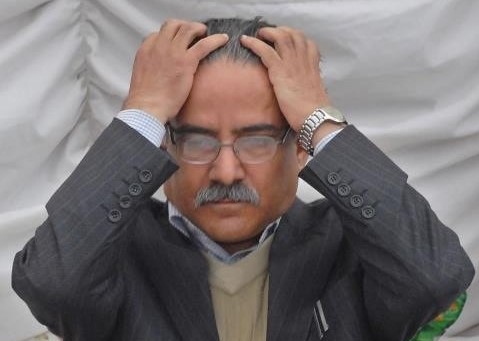

Prime Minister and Maoist party leader Pushpa Kamal Dahal is in trouble for his self-incriminating speech three years ago, where he claimed responsibility for 5,000 lives lost during a decade-long insurgency. Advocates Kalyan Budhathoki and Gyanendra Aaran on Tuesday filed separate petitions at the Supreme Court demanding legal action against Dahal.

“We are registering this case to bring to justice the people responsible for the atrocities and injustices committed against civilians during the conflict period,” said Budhathoki.

Aaran added they were compelled to knock on the door of the Supreme Court after their repeated calls to address the flaws seen in the transitional justice process went unheard. “We have filed the case on behalf of a handful of conflict-affected families, but in reality we are representing the families of 5,500 people killed at the hands of Maoist insurgents.”

Hearing on the case has been scheduled for Thursday. “Prachanda is not free to kill, nor order others to kill,” read one of the petitions. “His public proclamation of taking 5,000 lives is unlawful, so he must be arrested and prosecuted as per existing law.”

Maoists on the defense

The case against Prime Minister Dahal has rattled CPN (Maoist Center) and its breakaway parties. They issued a joint statement on Tuesday, saying they stand against any activity in contravention of the Comprehensive Peace Accord.

“Matters related to transitional justice must be taken through the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Any act that goes against the transitional justice process will not help in the implementation of the peace accord,” reads the statement. The statement was signed by the Maoist Center, Nepal Samajbadi Party, NCP (Revolutionary Maoist), Nepal Communist Party, CPN (Majority), Scientific Socialist Communist Party, CPN (Maoist Socialist), and Maoist Communist Party Nepal.

National rights body concerned

The National Human Rights Commission also issued a statement on Tuesday, calling on the government, political parties and other stakeholders to conclude the transitional justice process at the earliest. It asked all concerned parties to amend the transitional justice laws in accordance with international standards, and as instructed by the Supreme Court. The national rights body also raised concerns over the objections raised by some political parties concerning the case filed by the conflict victims in the apex court.

“Though transitional justice has a different set of rules and procedures, it is still unjust to bar conflict victims from gaining access to the court of law for justice,” said the statement. The commission said it is worrisome that Nepal’s transitional justice has not concluded even more than 16 years after the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Accord.

Raghuji Panta: Dahal has a shifty personality

CPN-UML has pulled out of the Pushpa Kamal Dahal-led coalition government in the wake of differences over the presidential candidate, for which a vote is due on March 9. This will likely create a new political coalition, including CPN (Maoist Center), Nepali Congress, and CPN (Unified Socialist). Pratik Ghimire of ApEx talked to Raghuji Panta, parliamentarian and UML leader regarding the current political scenario.

What’s your take on the latest political developments?

Nepali political leaders never follow their ideology, values, beliefs, plans, and policies and they never work for national interest is what Prime Minister Dahal showed recently. He quit the political alliance formed barely a couple of months ago. Why did he do so? His behavior and the new coalition will only deepen political instability.

This is not a new alliance though. The Congress, Maoists, and other parties were together till the Nov 20 polls. Did they deliver quality service to the people? No. This coalition got embroiled in plenty of scams like the involvement of an unauthorized person in budget preparation. So, what should people expect from them?

Why did Dahal betray the UML?

Dahal is a shifty person. Previously also, he had betrayed almost all political parties for petty gains. This time again, this is all for his benefit. Not only will this hamper the country but also his party.

Do you see an external role in the current turmoil?

The coalition, which included the UML and other parties, had more patriotic agendas. It is now proved that international powers don't like a left-centric government and they wanted the Congress in power by any means. There certainly is an external role in this political change, but we have to keep in mind that external forces can’t act without our political leaders. The external forces have used our political actors. We must criticize external interference in domestic politics, but our politicians must also work in the interest of the nation. They should ask external forces not to interfere in internal politics and convey a message that we are capable of solving our problems on our own.

Any chance of a Congress-UML alliance?

As of now, we have no such interest. We are determined to play the role of a perfect opposition by respecting the will of the people.

What is the UML’s grassroots mission? What are its objectives?

This mission has a simple meaning. We want to involve more youths in the party as they are our future. Being one of the large political parties, it is difficult to run the party’s affairs smoothly. Missions like this one help us connect with the people at the grassroots and help solve many problems. This mission also aims to bridge the gap between youths, laymen, and the party leadership, enabling the party to work for the people more effectively.

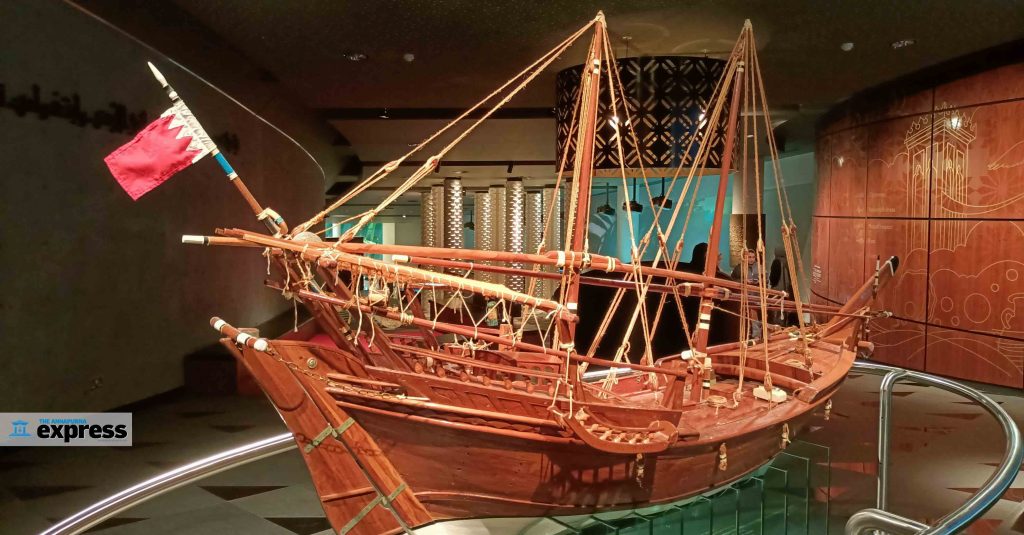

What I saw in Bahrain (Photo Feature)

Manama: The Kingdom of Bahrain invited a select group of journalists to participate in an event that was going to be held to honor Nepali ophthalmologist Dr Sanduk Ruit with the Isa Award for Service to Humanity. I happened to be one of the lucky seven who went to Bahrain.

An international trip, even though for work, is fun as you get to visit new places, see new things, meet new people, taste new food and experience new cultures. It was exciting for me not only because it was my first international trip but also because it was my first-ever flight experience.  Bahrain is an island country in West Asia comprising a small archipelago made up of 50 natural islands and 33 artificial islands. It spans some 760 square kilometers, and is the third-smallest nation in Asia. In light traffic, you can easily move from one corner of Bahrain to another within 20 minutes.

Bahrain is an island country in West Asia comprising a small archipelago made up of 50 natural islands and 33 artificial islands. It spans some 760 square kilometers, and is the third-smallest nation in Asia. In light traffic, you can easily move from one corner of Bahrain to another within 20 minutes.  Upon landing in Bahrain on February 19, I started comparing the city bathed in night-light with Nepal. I could see just how different it was from the moment I stepped off the plane. There’s a lot we can and need to learn from Bahrain.

Upon landing in Bahrain on February 19, I started comparing the city bathed in night-light with Nepal. I could see just how different it was from the moment I stepped off the plane. There’s a lot we can and need to learn from Bahrain.  Though located in one of the world’s main oil-producing regions, Bahrain has a handful of small oil wells. Among the gulf nations, Bahrain was the first to find petroleum reserves. We visited the historic well, now converted to an ‘Oil Museum’.

Though located in one of the world’s main oil-producing regions, Bahrain has a handful of small oil wells. Among the gulf nations, Bahrain was the first to find petroleum reserves. We visited the historic well, now converted to an ‘Oil Museum’.  I thought, being an Islamic state, Bahrain might have a strict society, but I found it to be completely different. A strikingly modern city, Manama, Bahrain’s capital, is relaxed and cosmopolitan and is a favorite destination for visitors from the neighboring Saudi Arabia. On weekends, crowds of Saudis come into the city to enjoy its restaurants and bars and the nightlife, which is rare in their country.

I thought, being an Islamic state, Bahrain might have a strict society, but I found it to be completely different. A strikingly modern city, Manama, Bahrain’s capital, is relaxed and cosmopolitan and is a favorite destination for visitors from the neighboring Saudi Arabia. On weekends, crowds of Saudis come into the city to enjoy its restaurants and bars and the nightlife, which is rare in their country.  However, traffic jams are an issue in Bahrain. On the weekend, congestion gets heavier than in Kathmandu. It could be because the small island country has no metros and fewer public buses and everyone eligible to drive has their own car. Many of them even have two—separate ones for office and personal use.

However, traffic jams are an issue in Bahrain. On the weekend, congestion gets heavier than in Kathmandu. It could be because the small island country has no metros and fewer public buses and everyone eligible to drive has their own car. Many of them even have two—separate ones for office and personal use.  The other places I visited were The King Fahd Causeway, Tree of Life, Bahraini Women’s Monument ‘Athar’ and the National Charter Monument. The Tree of Life is a 9.75 meters high Prosopis cineraria tree that has been standing on a hill in a barren area of the Arabian Desert for 400 years!

The other places I visited were The King Fahd Causeway, Tree of Life, Bahraini Women’s Monument ‘Athar’ and the National Charter Monument. The Tree of Life is a 9.75 meters high Prosopis cineraria tree that has been standing on a hill in a barren area of the Arabian Desert for 400 years!  What amazed me the most was the charter monument. It was commissioned by King Hamad al-Khalifa as a ‘gift to the people’ of Bahrain and to honor the National Charter (Bahrain’s Constitution). This building explores concepts and representations of national history and identity in a series of vivid, dramatic visitor experiences. Over 220,000 names are engraved on the walls of this monument—of those who voted during the promulgation of Bahrain’s first Constitution.

What amazed me the most was the charter monument. It was commissioned by King Hamad al-Khalifa as a ‘gift to the people’ of Bahrain and to honor the National Charter (Bahrain’s Constitution). This building explores concepts and representations of national history and identity in a series of vivid, dramatic visitor experiences. Over 220,000 names are engraved on the walls of this monument—of those who voted during the promulgation of Bahrain’s first Constitution.  There are many takeaways from my Bahrain trip. Apart from being a fun experience, it also opened my eyes to how impactful government policies and infrastructural development plans can be to create a wonderfully equipped and thus habitable state.

There are many takeaways from my Bahrain trip. Apart from being a fun experience, it also opened my eyes to how impactful government policies and infrastructural development plans can be to create a wonderfully equipped and thus habitable state.

Dahal loses key ally: Time for another floor test

CPN-UML has pulled out of the Pushpa Kamal Dahal-led coalition government over a presidential candidate dispute. Days after the Rastriya Prajatantra Party quit the government, the UML ministers also tendered their resignation. UML was the coalition linchpin that elevated Dahal to power for the third time on Dec 25 last year. But the coalition broke down within just two months after the prime minister refused to back UML’s presidential candidate.

With UML and RPP out of the government, and another coalition partner, Rastriya Swatantra Party, having previously recalled its ministers over the citizenship controversy of its leader Rabi Lamichhane, 16 ministries are now without ministers. As per article 100 of the constitution, the prime minister should now take a vote of confidence from Parliament.

The article states: “In case the political party, which the Prime Minister represents, is divided or a political party in coalition government withdraws its support, the Prime Minister shall table a motion in the House of Representatives for a vote of confidence within 30 days.”

Experts, however, say that Dahal doesn’t have the luxury of taking 30 days to take Parliament’s floor test, as the major parties that supported him have pulled out from his government. Lamichhane’s RSP is the only party that has not decided to withdraw its support to the Dahal government, despite recalling its ministers.

Constitutional expert Bipin Adhikari says this is not a normal situation for the prime minister. “Dahal’s major coalition partners have quit, so he must take the vote of confidence without any delay.” Without the trust vote, Adhikari adds, the prime minister, who has essentially lost the majority, cannot engage in major parliamentary business.

Dahal was appointed prime minister with the support of 169 members in the 275-strong House of Representatives. The UML (78) and RPP (14) together made 92 votes. Dahal’s party had secured only 32 seats in the parliamentary election held on November 20 last year. Without the UML and RPP support, his government has been rendered into a minority.

But with the main opposition, Nepali Congress, and other fringe parties behind Dahal, he is confident about saving his premiership. Preliminary talks are already under way to form a new coalition.

Tirtha Raj Wagle: Operation of direct flights could boost ties

Nepal and the Kingdom of Bahrain have been enjoying cordial ties ever since the two countries established official diplomatic relations in 1977. Over the years, Bahrain has become an important destination for Nepali migrant workers. Pratik Ghimire of ApEx caught up with Tirtha Raj Wagle, Nepali ambassador to Bahrain in his office, to talk about the condition of Nepali workers and various aspects of Nepal-Bahrain bilateral relationship.

What is the Nepal Embassy doing for Nepalis living in Bahrain?

Bahrain has about 21,000 Nepalis. Most of them are working low and semi-skilled jobs. For their supervision, we keep a close connection with them and discuss their issues. Whenever there are issues, such as unpaid wages or medical help or over time payment, we talk with the concerned employers. These issues are usually solved at our request.

We do follow-ups to make sure the workers’ problems are being addressed. If that doesn’t work, we take up the issue with the Labor Ministry and Labor Market Regulatory Authority. We also coordinate with manpower companies and the Nepal government if the Nepali workers are sent here without proper agreements.

What is the current condition of Nepalis working in Bahrain?

I have found that Nepalis in Bahrain are happy with their living and working conditions here. The Bahrain government and the people also love Nepalis for their hard work, dedication and honesty. The market for jobs, yet isn’t huge in Bahrain. The population here is roughly about 1.5m, where half of them are foreigners and around 21,000 are Nepalis. The Bahrain government has a policy where skilled laborers are given priority. So, greater job opportunities are available for people with skill sets, education and language. Currently, Nepal is only supplying low skilled laborers.

For Nepalis working low-skilled jobs, how is the embassy making sure they are not deprived of their basic rights?

The embassy contacts the respected companies and conducts inspection visits of their workplace. We also visit the living quarters of Nepali workers to make sure they are living well. If we notice any issue, we send a complaint to the authorized company and the problem will be sorted out. But we do not always get permission from companies to inspect the living quarters and workplaces, which is a problem we are trying to solve with the cooperation of the Bahrain government authorities.

For the management of the labor market, there was a labor agreement between Nepal and Bahrain. How is that helping Nepali workers?

We had a labor agreement in 2008. Nepal and Bahrain have also agreed to conduct routine technical level conferences of their labor ministries. So far, our focus has been on insurance and workers’ safety, as well as providing necessary training to the workers. The areas of priority are conducting orientation programs and training for the new workers. The two countries have not yet agreed on a minimum salary range for Nepali workers.

But we are lobbying with the Bahraini government on this. I can’t say what will be the progress as there have not been any meetings recently regarding the minimum salary range. But from our side, we have recommended bacis salary for the workers. For instance, 100 BD for unskilled, 120 BD for semiskilled, 150 BD for skilled and 550 BD for professionals. We have also recommended certain allowances for all type of workers.

Has there been any agreement on managing the investments made by Nepalis?

Few Nepalis have been conducting small businesses in Bahrain. In order to improve their business structures, they want an exchange of business delegations or some kind of agreement. The Nepali Embassy and the government are in support of business delegation exchanges, as well as investment agreements and double taxation avoidance agreements. But as of now, Nepal and Bahrain have not reached any such agreements. But we are planning to hold a bilateral conference to discuss various areas of labor, tourism, trade, education and hospitality.

As of now, due to the lack of business agreement between both countries, any Nepali who wants to invest, has to ensure that they can only keep a financial share of 49 percent. 51 percent share should be of a local Bahraini citizen. We are in regular communication with both governments to conduct a diplomatic consultation of foreign ministry-level meetings or at least foreign secretary-level meetings.

There are reports about establishing ‘Bahrain Peak’ in Nepal. How is the plan coming along?

The Royal Guard Team, which is under the Bahrain Defense Force, has successfully climbed many mountains of Nepal including the Sagarmatha, Manaslu, Lobuche and Ama Dablam. So Bahrainis have a close affinity with Nepal, particularly our mountains. This has helped in the marketing of Nepali mountains and hills in Bahrain.

A local government of Gorkha and the local people have agreed to name one of the hills in Gorkha as ‘Bahrain Peak’. I personally am unaware about the latest development on this matter, but I am sure it is being taken positively by all the concerned parties.

Dr Sanduk Ruit has just won the Isa Award for Service to Humanity. What message has it given to the Nepalis in Bahrain?

Every Nepali in Bahrain is proud of Dr Ruit for winning the prestigious award and representing Nepal. They expect to see Dr Ruit visiting Bahrain for a health exchange program and further the ties between the two countries. This has also opened Nepal for health tourism.

Nepal has brought different schemes for foreign investment. Which of the sectors do you think Bahrain should invest in?

Currently, the tourism sector is the focus of the Bahrain government. They are also interested in sports tourism, youth activities, ecotourism, and hydropower generation. But they need more planning and visualization. I have assured them that our service and other sectors are also good to invest in and have also asked them to visit Nepal and study more on it.

Nepal and Bahrain lack direct flight connection. Is the Nepali Embassy doing anything about this?

The lack of direct flight has created problems. In order for Nepalis to run their business, to import local products from Nepal, direct flight would have made it so much easier. For example, during our national days, we have shown our organic products like tea, coffee and himalayan water and the Bahranis looked interested in the taste and trade.

The same goes for tourism. Visitors still have to go through a 12-hour travel time between the two countries but it could be reduced to five to six hours in case of direct flight. The embassy has been trying to open a direct flight service, at least two flights per week, in cooperation with Nepal Airlines and Himalaya Airlines, but nothing has come of it so far. We are still trying.

Bahrain does not have its embassy in Nepal. Its mission in Delhi handles the affairs concerning Nepal. Do you think this has affected the bilateral communication between Nepal and Bahrain?

I don’t see any problem with Bahrain not having its dedicated embassy in Nepal. Its embassy in Delhi has been supervising and overseeing the bilateral matters with Nepal quite smoothly and consistently, I must say. We communicate with them regularly. If necessary, Nepal and Bahrain can discuss and plan ways to improve bilateral relations through the Delhi mission. Until now we have not encountered any issue with this communication arrangement.