Dr Ruit honored with prestigious Isa Award

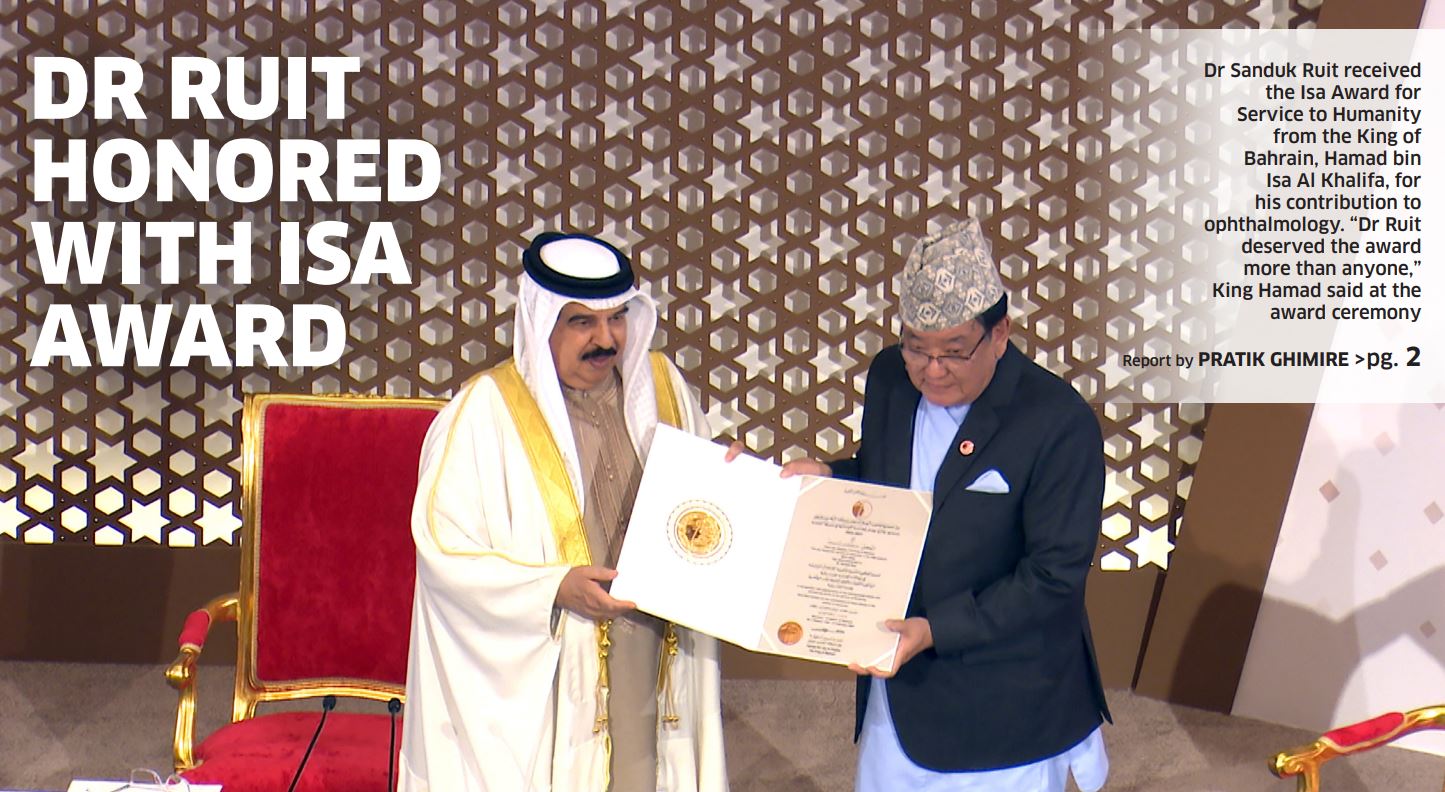

Manama (Bahrain): Nepali ophthalmologist Dr Sanduk Ruit was presented with the Isa Award for Service to Humanity amid an event at the Isa Cultural Center in Manama, the capital of Bahrain, on Tuesday. The King of Bahrain, Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifa, presented the award to Dr Ruit in recognition of his contribution to the field of ophthalmology.

Dr Ruit was the first Nepali doctor to perform cataract surgery with intraocular lens implants and the first to pioneer a method for delivering high-quality microsurgical procedures in remote eye camps across the world. He is best known for restoring the sight of over 180,000 people across Africa and Asia.

“Dr Ruit deserved the award more than anyone," King Hamad said. "This award, which carries distinguished, fond and broad memories, resembles an important guide to exploring human achievements on the global stage, making service to mankind a humanitarian duty.”

He dedicated the award to millions of patients, their families, his team and the entire Nepali people. “I’m sure that this award will further inspire serious humanitarian work being done in different parts of the world irrespective of their political, social, geographical and economical connectivity,” he said.

Dr Ruit hails from Olangchunggola, a remote village on the border of Tibet in Taplejung district of northeast Nepal. He made his life goal to become a doctor and serve the communities that do not have access to sufficient healthcare after losing his sister to tuberculosis.

The award, named after the late Emir Shaikh Isa bin Salman Al Khalifa, was established in 2009 and carries a purse of $1m. It is granted every two years to either individuals or organizations selected through a grueling process by an expert panel of jurists. The award doesn’t entertain political organizations, associations or trade unions.

Altogether 145 candidates from across the world had applied for the award this time and 139 applicants were accepted. The accepted applications were again shortlisted to five, in accordance with the terms and conditions of the award.

The Board of Trustees of the award committee then dispatched a field team to visit the locations of the five short-listed applicants to evaluate their conformity with the award criteria. The team started their trip at the Institute of Ophthalmology in Kathmandu and then went to the Hetauda Community Eye Hospital to look at the mobile field hospitals and met with Dr Ruit and his staff of doctors, nurses, and technicians.

They also visited the operating rooms for lens implantation at both stationary and mobile hospitals in different rural and mountainous locations, where they spoke with patients about the intricacies of their situations and got their honest feedback. According to the research team, their field proved that the innovative nature of Dr Ruit’s medical and humanitarian efforts is diverse.

“Every individual should do humanitarian work like Dr Ruit and previous laureates,” said Shaikh Mohammed bin Mubarak Al Khalifa, special representative of the king and chairman of the Board Trustees of Isa Award for Service to Humanity.

Dr Ruit is credited for developing a cost-effective lens as well as pioneering a new way of performing medical surgery that minimizes collateral damage and shortens the recovery period. To meet the demand for low-cost eyeglass lenses, Dr Ruit established a factory in his hometown that manufactures over 350,000 lenses each year. Whereas it costs $100 to make a single lens elsewhere, Dr Ruit’s factory distributes them for $3 each.

According to peer-reviewed scientific research, the lenses produced at Dr Ruit’s institute are of equivalent quality to their more expensive counterparts in the developed world, and their low cost is the outcome of the refinement of production processes and procedures over more than 30 years. Besides, Dr Ruit has also trained over 650 doctors from across the globe, who are now following his footstep in a fight against preventable blindness. They have conducted more than 35m surgeries so far.

Dr Ruit’s institute provides ophthalmic care to patients in Nepal in two hospitals and 16 clinics, staffed by around 30 doctors. There are medical professionals from all over the world, including in the United States, Africa, and several Asian countries. His new method for treating cataracts helped him in performing cataract surgeries in less than five minutes during which he removes the cataract without stitches through small incisions, and replaces them with a cost-effective artificial lens.

Dr Farhan Nizami, one of the jury members, said awarding Dr Ruit means recognizing the work of his institution and motivating others to work for humanity. “This award is a monument of hard work and it is proved by our laureate Dr Ruit,” he added.

Dr Sanduk Ruit: We will expand our services everywhere needed

A short interview

What is the impact of the award?

Capacity building is one of the main impacts as this prestigious award facilitates us with more resources. The impartiality, inclusiveness and a serious attempt to find game changing humanitarian work even at a far-flung grassroots level is a motivation for everyone. I think this Isa Award is the most impartial among the large global awards. Without any political and geographical powers, these days, it is impossible to get such awards. So it has many such beautiful impacts.

What is your plan for the expansion of eye care service?

The prevalence of cataract in Nepal is high but we have taken care in the last decade. So we are moving to other countries too. Due to our good quality, even our neighboring countries' patients come to Nepal for the treatment. We will expand our services everywhere needed.

How sustainable is your treatment technique?

One of our main works is training doctors from rural areas. We pick up a few local surgeons and help them continue their work in the highest quality. So by passing our knowledge, we are making sure this treatment technique continues. Also, in 1989, WHO didn’t allow my team to conduct cataract surgeries, saying that these things need a high clinical trial. But to date, not a single patient has complained about our lens. So it’s sustainable for sure.

What are your further plans?

We are planning a mass treatment of 30,000 patients in Ghana and Ethiopia this year. We are committed to all people who can’t get quality healthcare services. We'll get everywhere soon.

Isa Award recipients

1st laureate-2013

Dr Tan Sri Jemilah binti Mahmood, a Malaysian physician became the first recipient of Isa Award for Service to Humanity for her efforts in disaster prevention and relief, education, community services, environment protection, climate change, and poverty alleviation. She is one of the rare Muslim women who have broken through the humanitarian world’s glass ceiling and helped redefine women’s roles and responsibilities. Her focus, passion, energy and experience—involving crises in places like Kosovo, Iran, Iraq, Palestine, Sudan, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Myanmar, Sri Lanka and Indonesia—have led to astounding results in the field.

2nd laureate-2015

Achyuta Samanta is an Indian educationist and philanthropist. He is the founder of Kalinga Institute of Industrial Technology and Kalinga Institute of Social Sciences. His institute is regarded as a world-class university that caters to 25,000 children from the underprivileged tribal community. The institute was started with an investment of just IRs 5,000. His vision is to provide quality education and opportunities to the poorest of the poor indigenous tribal children, boosting their all-round development and empowering them with life skills so that they can successfully integrate into the mainstream. Dr Samanta was awarded for his relentless quest to help those languishing in abject poverty and for establishing a conglomeration of educational institutions.

3rd laureate-2017

Children’s Cancer Hospital Egypt, also known as Hospital 57357 after its widely published bank account number for donations, is a hospital in Cairo specializing in children's cancer. With 320 beds, the building is the largest pediatric oncology hospital in the world. The hospital is a unique institution. It was built by donations, and even today, continues to operate and to be sustained through donations. It was established in 2007 with the goal of providing the best comprehensive family-centered quality care and offering a chance for a cure to all children with cancer seeking its services and it would be provided to them—free of charge and without any discrimination. The hospital is recording a 72 percent average over-all survival rate. It is more than a hospital but stands as a leading example for healthcare, a change agent and a comprehensive institution for fighting childhood cancer.

4th laureate-2019

Edhi Foundation is a non-profit social welfare organization based in Pakistan. In 1951, it was founded by Abdul Sattar Edhi, a well-known Pakistani philanthropist, ascetic, humanitarian, and social activist. He is known as the ‘Father of the Poor’ and ‘The Angel of Mercy,’ and has been constantly nominated for the Nobel Prize for Peace. He established a giant charity foundation that sponsored the building of maternity hospitals, morgues, orphanages, shelters and a nursing home. Until his death in 2016, he dedicated his life and that of all his family members to the service of people.

The Edhi Foundation has orphanages attached to primary and secondary schools; homes for the disabled, rejected and displaced children, and drug addicts; and shelters for abused women. There are also maternity centers, family planning centers, training institutes for nurses, blood banks, a tuberculosis clinic and a tumor hospital. The foundation runs 330 care centers in Pakistan’s rural and urban areas, providing food, shelter and rehabilitation for abandoned women and children, as well as medication for mentally ill patients. The foundation has provided relief work in Africa, the Middle East, the Caucasus, Eastern Europe and the United States (during Hurricane Katrina in 2005).

Dr Ruit honored with Isa Award

Manama (Bahrain): Renowned Nepali ophthalmologist Dr Sanduk Ruit was honored with the Isa Award for Service to Humanity amidst an event organized at the Isa Cultural Center in Manama, the capital of Bahrain, on Tuesday. Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifa, the King of Bahrain, handed the award to Dr Ruit.

“Dr Ruit deserved the award more than anyone,” King Hamad said. Shaikh Mohammed bin Mubarak Al Khalifa, special representative of the king and Chairman of the Board Trustees of Isa Award for Service to Humanity, said that every individual should do humanitarian work like Dr Ruit and previous laureates.

Dr Farhan Nizami, one of the jury members, said: “Awarding Dr Ruit means recognising the work of his institution and motivating others to work for humanity. This award is a monument of hard work and it is proved by our laureate Dr Ruit.”

Expressing his happiness, Dr Ruit said that he will be a great ambassador for this Isa Award. “I accept this prestigious award on behalf of millions of patients, their families, my team and the entire Nepalis whose goodwill and best wishes I bring to this distinguished gathering,” he added.

Earlier at a press briefing, on Feb 20, Minister of Information of Bahrain Ramzan bin Abdullah Al-Nuaimi said: “Nepal is often hailed as a country of kind people and this achievement of Dr Ruit has proved that.” The fifth edition of the award, which carries a purse of $1m, recognizes Dr Ruit’s contributions to human service through eye treatment. The award, established in 2009 by King Hamad, is granted every two years to either individuals or organizations selected through a grueling process by an expert panel of jurists.

In search of an impartial president

Who should be the next president?

Come March 9, Nepal will elect a new president. It will be the fourth presidential election after Nepal became a federal republic in 2008. This time, however, the issue of presidential candidates has become a contentious topic among major political parties. It has threatened the unity of the nascent ruling coalition. CPN-UML, a primary coalition partner in the CPN (Maoist Center)-led government, wants the top job for its candidate.

Incumbent President Bidya Devi Bhandari, also a UML pick, has already served as the head of state for two successive terms. Prime Minister Pushpa Kamal Dahal, meanwhile, is not keen about the idea of supporting a UML candidate. With the opposition, Nepali Congress, also in the presidential race, Dahal wants a national consensus candidate. Given the checkered legacies of the presidents hitherto—Bhandari and her predecessor Ram Baran Yadav—who were criticized for being partial toward their respective parties, there is a call for a nonpartisan candidate, who can stay above petty party politics.

In this context, Pratik Ghimire spoke with politicians and experts to solicit their views on what kind of president they would prefer.

Ghanashyam Bhusal, Leader, CPN (Unified Socialist)

We have a ceremonial presidential system, so it is important for the candidate to honor that role of nominal head of state. If the president starts abusing his or her power, it can create problems. The president should be the person who could protect the constitution by exercising the rights and duties as provided for by the constitution. This is why it is important that the next president is elected based on national consensus.

Tula Narayan Shah, Political analyst

The president should be that person who understands politics and can keep the prestige of the position. The previous and the current president were active members of political parties. That's not a problem in itself, but they acted like a puppet of their parties, which is a problem.

Bipin Adhikari, Constitutional expert

There is no problem with the presidential candidate coming from a political background. But once elected, he or she must be able to maintain national unity and preserve the constitution. As the prime minister is an advisor of the president, there will be no problem even if the president is apolitical. If a political party leader who is actively involved in politics and has already served as a minister were to become the president, it will be difficult for him or her to maintain the dignity of the office. So, the important thing is his or her capacity to stay neutral and not get involved in party politics. Also, as Nepal has already elected a female and a Madhesi president, I would like to see the next president to be from a Dalit, indigenous or minority community.

Meena Poudel, Political analyst

We are in a multiparty competitive democratic system. And if we are asking for an apolitical president, it will not be in accordance with our system. So, the president must be a political person, not an active cadre but a political person. The tenure of two presidents have suggested that the president should stand above the political parties for national unity and integrity. If we put a person who has no political knowledge, it will hamper our political system and institutional framework.

Narayan Dahal, Standing Committee Member, CPN (Maoist Center)

The president should be the person who can rise above the parties and lead the country. The need for that kind of leadership has become urgent. So, a national consensus will help to bring the country to stability. We have asked this coalition to find a common character and form a common candidate in the presidential election. In which we also have to bring the Nepali Congress as the Congress has also given a vote of confidence to the prime minister. It should not be sought outside of political consciousness. We want a person who understands the national agenda. That person can be from any party. It can also be a person who has been in politics but is now independent. An independent person who will not advance the agenda of a party but accepts the achievements like federalism, republicanism and secularism is what we want.

Puranjan Acharya, Political analyst

There is no problem if Nepal gets a political or apolitical figure for the president because the president must abide by the constitution. He or she should not go beyond the constitutional framework. The president should act as a defender of the constitution. But the two presidents we have had so far ran into controversies for not maintaining the dignity of their position. President Bidya Devi Bhandari has not maintained the single criteria that the constitution suggests. Former president Ram Baran Yadav was slightly better than her. He, at least, did some good work. So, for now, the new president should at least be like Yadav.

Indra Adhikari, Political analyst

We have already seen two presidents, and they were enmeshed in so many controversies. They didn’t try to establish the president’s office as an honored institution, which hampered our political system. So, the time has come to elect a president who could safeguard the constitution without being influenced by political parties. There are capable leaders within the political parties who can become a good president. Personally, I think an individual from a marginalized community should be elected the head of state.

Khim Lal Devkota, Member, National Assembly

Even if the president is a political outsider, he or she can be a good head of state so long as they possess good moral conduct. An ideal presidential candidate should have achieved a national height in his or her field. Our previous and current president tried to work against the constitution several times. So, we must elect a president who can really work within the bounds of the constitution and champion national unity.

Nain Singh Mahar, Leader, Nepali Congress

I, personally, want a political figure for the president, but that doesn’t mean there aren’t apolitical individuals who are capable of the role. I think the presidential candidate should have a good understanding of the Nepali politics, or else he or she will not be able to work according to the constitution? Ideally, a person who was actively involved during the drafting and promulgation of the constitution could make a good presidential candidate. The candidate should also be far-sighted, someone who can take bold decisions.

Bishnu Rijal, Leader, CPN-UML

As the president is the apex position in politics, the person for the job should also be a political figure from a political party. An experienced and knowledgeable person who could show a light during a crisis should be the next president. I don’t think that an apolitical person, a retired bureaucrat, or a civil society member is suitable for the job of a president.

Functions, duties and powers of President:  (1) The President shall exercise such powers and perform such duties as conferred to him or her pursuant to this Constitution or a Federal law. (2) In exercising the powers or duties under clause (1), the President shall perform all other functions to be performed by him or her on recommendation and with the consent of the Council of Ministers than those functions specifically provided to be performed on recommendation of any body or official under this Constitution or Federal Law. Such recommendation and consent shall be submitted through the Prime Minister. (3) Any decision or order to be issued in the name of the President under clause (2) and other instrument of authorization pertaining thereto shall be authenticated as provided for in the Federal law.

(1) The President shall exercise such powers and perform such duties as conferred to him or her pursuant to this Constitution or a Federal law. (2) In exercising the powers or duties under clause (1), the President shall perform all other functions to be performed by him or her on recommendation and with the consent of the Council of Ministers than those functions specifically provided to be performed on recommendation of any body or official under this Constitution or Federal Law. Such recommendation and consent shall be submitted through the Prime Minister. (3) Any decision or order to be issued in the name of the President under clause (2) and other instrument of authorization pertaining thereto shall be authenticated as provided for in the Federal law.

Rupak Sapkota: Concrete plan necessary to deal with geopolitical flux

Tensions between the US and China are increasing day by day and its implications are already felt in Kathmandu. The Pushpa Kamal Dahal-led government faces an herculean task of managing a balanced and trustworthy relations with all major powers to reap benefits from their economic development.

In this context, Pratik Ghimire talked to Rupak Sapkota, a foreign policy expert to solicit his views about Nepal’s changing foreign policy picture and geopolitical situation.

What is your view on the recent shifting of geopolitical tension in the Himalayan belt?

Over the past few years, big powers have adopted an assertive foreign policy. Let’s ponder the ongoing Russia-Ukraine war and the position taken by major powers. America and its traditional allies are providing arms and ammunition to Ukraine. Similarly, it is also urging its Asian allies to stand in favor of Ukraine and provide weapons. American military and diplomatic officials are undertaking a world-wide tour to advance their agenda. On the other hand, strategic relations between China and Russia have been developing and growing too. At the same time, Xi Jinping has been re-elected for the third consecutive term, and the political document endorsed by the Chinese Congress shows that China desires to change the world order in its favor.

China has the economic and diplomatic strength to undo the existing world order. America is enhancing its presence in the Indo-pacific region with a primary goal of containing China. It has launched a fresh campaign to re-energize its alliances both in Europe and Asia. China, meanwhile, is adopting a dual strategy. Its immediate priority is not to alter the existing world order but to exploit its industrial and technological advantage. At the same time, China also wants to promote its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) with a mantra of human community with a shared future. America’s leadership is becoming weak and in this context, China along with Russia and other emerging economies, who want to see change in the current world, are advocating for a new world order. In a nutshell, world powers are heading towards a bitter conflict and confrontation. And in this scenario, the countries of the global South are particularly fearful that they could be trapped in the stiff geo-political contest between the US and China.

NATO has been paying close attention to Asia. Does this mean the geopolitical tension will further increase in future?

This is entirely a new global phenomenon that we had not seen after the second world war. Over the past few decades, America was obviously paying attention to Asian countries but NATO’s Asia pivot is a new development. America is working at a structural level like QUAD and AUKUS but NATO’s direct communication and engagement with Asian countries is rare. The NATO chief recently visited Japan and South Korea, and is likely to visit India as well. The primary objective of NATO’s move is to secure more arms and ammunition for Ukraine, and the second is to enhance military and strategic cooperation with India, which is projected as a pillar of the Indo-Pacific region. India’s defense cooperation with Russia is strong and robust. And since India has adopted a policy of neutrality in the Russia-Ukraine war, it has made the US unhappy. NATO, America and other Western powers want to minimize India’s military dependence with Russia.

Over the past few years, the defense cooperation between India and US is increasing, which has been reflected through plus-two dialogue. This aims to minimize India’s defense cooperation with Russia. At the same time, India and China have been locked in a bitter border dispute since 2018, and there are no signs of rapprochement despite the dialogue between two Asian powers. Both India and the US view China as a common security threat. So, it seems that geopolitical gravity is gradually shifting to Himalayan region. America has been trying to upgrade its cooperative relationship with India for three reasons: to enhance the influence of the Indo-Pacific region; to contain China; and to minimize India’s defense dependency with Russia.

How do you see the recent US engagement with South Asian countries including Nepal?

As stated earlier, America is expanding multi-layer engagement with Asian countries and Nepal is also an important priority. Obviously, Nepal’s geopolitical location drives big powers to engage with us. A recent report from the International Monetary Front has shown the growing economic might of China as well as India. And since Nepal is between these two powers, it may have driven America to engage more with us. America’s economic engagement with Nepal, be it through MCC or other forms, is gradually increasing. The series of visits of American officials show that Nepal-US bilateral relations will further enhance in the coming days. Nepal’s geopolitical location has driven the US to engage more with Nepal.

Lying between the world’s two greatest economies, Nepal occupies an important position. Frequent visits of American officials show our relationship and engagement with America has expanded. America’s Indo-Pacific Strategy (IPS) has come up with a holistic approach—military, economic, governance and politics, trade and connectivity. Though American officials are not vocal about it, the US is conducting all its activities and assistance in this region through IPS.

How is the Nepal government preparing or dealing with these issues?

After the promulgation of a new constitution in 2015, Nepal has failed to navigate the fast-changing geopolitics, and does not have any plan on how to manage the competing foreign powers and pursue our national interest. There is a state of confusion on how we conduct our foreign policy in the current geopolitical flux. In many ways, I see a strategic void. Over the past few years, big powers have come up with different strategies, such as America’s Indo-Pacific Strategy. Nepal was asked to join the IPS during our foreign minister’s America visit in 2018. We endorsed the MCC with declarative interpretations and we have told big powers that we cannot join any military strategies. Similarly, we are moving ahead with China to cooperate on the economic front of BRI and other projects, but we have failed to make any substantial progress. India, too, is coming up with aggressive strategies.

Agnipath is a case in point. It is yet to be seen how the new government tackles the Agnipath scheme. The spillover effects of geopolitical rivalry have already been felt in Kathmandu, but we do not have any plan on how to push our economic agenda amid such strategies. This is a major challenge of the new government led by Pushpa Kamal Dahal. We should carve out a clear strategy of staying away from intense geopolitical rivalry and engage with big powers on clear economic terms. Development, prosperity and good governance are our key priorities, and to achieve them, we have to build international cooperation. We need to collaborate with all big powers on economic issues.

What are the key priorities of the Dahal-led government?

The Dahal government should conduct international relations focusing on three key priorities. First, staying away from military engagement with big powers while accepting economic assistance and investment. Second, it should conclude the remaining tasks of the peace process by taking the international community into confidence. And third, it should enhance climate diplomacy and raise Nepal’s climate vulnerabilities in the international forum. Along with these priorities, Nepal should also enhance its diplomatic outreach through multilateral agencies like SAARC. The new government should play an active role to revive the SAARC process.

What’s in store for RSP after Lamichhane’s anti-media rant?

Has Rabi Lamichhane dug a hole for himself and his up and coming party with his Sunday’s press conference? The leader of Rastriya Swatantra Party (RSP), who recently resigned as home minister over dual citizenship and passport controversy, has accused the press, publishers, and even some Twitter users of launching a witch hunt against him and his party.

Lamichhane had organized the press conference to announce the party’s decision to recall its ministers from the government, but he took no time to turn the briefing into a bizarre mudslinging fest, where he mostly attacked the media. Political analyst Lokraj Baral said Lamichhane’s action has done more harm to his nascent party than good. Baral compared the RSP with the party led by Dr KI Singh and Gorkha Parishad that were formed following the first democratic election of 1959.

“They too had won around 15-20 seats in parliament, but could not secure their political future,” said Baral. “It may appear like Lamichhane exposed the national media with his press conference, but his attitude was also exposed as that of other political leaders. This could hamper the future of his party in the long run.”

ApEx contacted several RSP central committee members and parliamentarians for their comments regarding Sunday’s incident, but most of them declined to talk about it. One central committee member, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said Lamichhane had called the press conference without informing the party members. “Most of the party members didn’t know what he was going to say in the conference,” said the RSP central committee member. Another party leader and lawmaker said it was Lamichhane who decided to recall the party ministers, not the central committee. “Other ministers could have won the public trust with their work,” said the leader.

Ganesh Karki, central committee member, wrote on social media that the person himself (Lamichhane) must defend his statement since it was not formally/informally discussed in the official meeting of the party. Minister of Education, Science and Technology Shishir Khanal and State Minister of Health and Population Dr Tosima Karki were not present at the press conference, while most of the party lawmakers and central members left the party office after the central committee meeting.

The RSP was formed around six months ago as an alternative political force and contested the general elections of 20 Nov 2022. The party won 20 seats in the federal parliament to become the fourth latest party, and decided to join the coalition government led by Pushpa Kamal Dahal. Lamichhane was appointed the deputy prime minister and home minister. But trouble began when it was revealed that Lamichhane had contested the election by submitting an invalid citizenship document, and the constitutional bench of the Supreme Court voided his status as a lawmaker and minister. Lamichhane has since obtained a valid citizenship, but he could not retain his lawmaker and minister’s status.

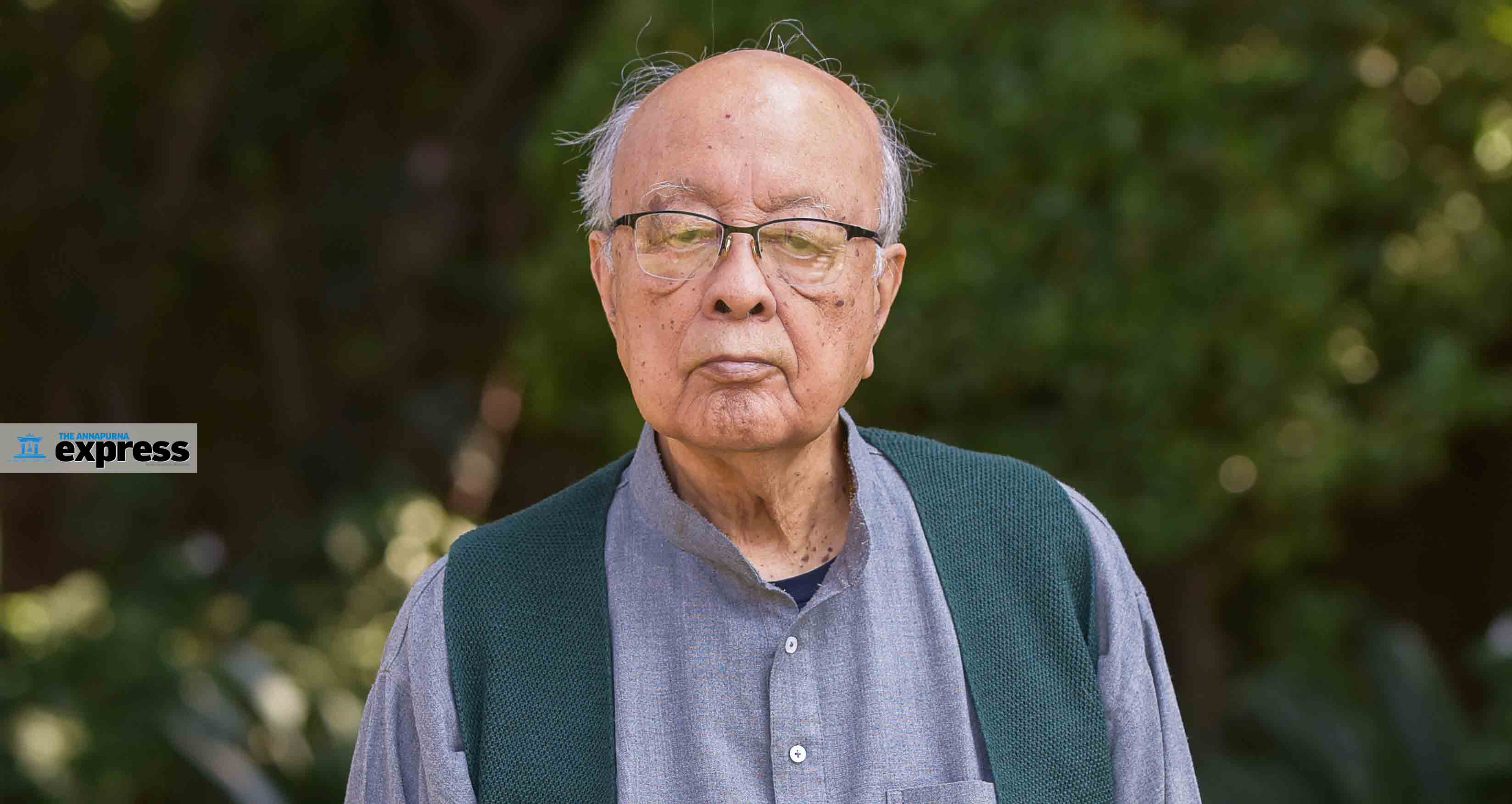

Himalaya Shumsher Rana obituary: Passing of a pioneer

Birth: 8 Jan 1928, Kathmandu

Death: 5 Feb 2023, Kathmandu

Himalaya Shumsher Rana, the first governor of Nepal Rastra Bank, breathed his last on February 5 in Kathmandu, leaving behind a rich legacy. The reputed economist (95) passed away on Sunday in the course of treatment at the Thapathali-based Norvic Hospital. While he will primarily be remembered for his role in the establishment of the central bank, Rana has many other laurels under his belt. He was instrumental in establishing Himalayan Bank, Nepal's first private sector bank after 1990, and setting up Gorkha Brewery and Himalayan Distillery. Rana, the great-grandson of the then Prime Minister Dev Shumsher Rana, held the position of the governor from 26 April 1956, to 7 February 1961.

After a successful tenure as finance secretary, Himalaya Shumsher Rana was offered the job of governor at Nepal Rastra Bank by the then King Mahendra. As there was no central bank in the country, the king gave him a book that had a draft of the Banking Act. But Rana requested that he would need some time to study the acts of central banks of foreign countries and only start the process of establishing Nepal’s central bank.

At first, he established a central office, an office for banking transactions, and a note department. After almost six months of homework, he was appointed the governor on 26 April 1956. With a small team, Rana started working to realize King Mahendra’s dream. He had two major concerns: to introduce Nepali notes in the Tarai, and stabilize an exchange rate between Rs and InRs. During those days, the Nepali currency was not in use in the Tarai, so much so that it was customary to take the land revenue and immigration duties in Indian currency.

In such a situation, replacing Indian notes with Nepali ones was a challenging task. Unless there was a stable exchange rate between Rs and InRs, it was not possible to circulate Nepali currency in the southern plains. The team researched for three years and came up with an exchange rate of Rs 160 for InRs 100. To date, Nepal uses the same rate. Rana and the team then established currency exchange centers from the east to the west. Nepali notes were printed at Nashik Security Press in India back then. After the establishment of the central bank, the central bank called for an international tender because the revision of the notes being printed in India was a must.

A proposal from a company from the UK was considered the best as it came up with a new design for notes bearing the pictures of famous places of Nepal. It was very nice and attractive. The notes printed in India also did not have the security thread; it was added on to the notes printed in the UK. After serving as the governor for four years and eight months and almost two months since King Mahendra banned political parties and started a dictatorial regime, he was sacked on 8 Feb 1961 because of being a supporter of democracy.

Rana then worked as a representative in various countries from 1962 to 1986 under the United Nations Development Program. He worked in Pakistan, Sri Lanka, America, Afghanistan, Myanmar, and Indonesia.

In an ApEx Pioneers column of The Annapurna Express, Rana said ever since he became the finance secretary, he had worked tirelessly. “After retirement, I tried to spend my time playing golf and reading books. But I got bored after six months and decided to start a business. I established the Gorkha Brewery Company and brought international beer brands like Tuborg and Carlsberg to Nepal. I also established the first private bank in Nepal, Himalayan Bank Ltd.” Among many national and international recognitions, he was conferred with the title of The Order of Japan (The Order of the Rising Sun, Gold and Silver Star) for his contribution. Former governor Chiranjibi Nepal described Rana’s demise as a huge loss for the banking sector. “Without him, the Nepali currency would not have found its place for a long time,” he says.

“The establishment of the first private bank was itself a milestone back then as it opened the door for aspiring bankers.” Rana’s friend Kiran Pyakurel remembers him as an admirable man. “Though born to a Rana family, he always advocated for democracy, which also cost him the post of governor,” he says: “I am inspired by how he never lost his learning spirit and has managed to remain curious all his life. No matter his age, he is always curious to learn about new things.” Rana is survived by two daughters and two sons.

Simrik Air expertise to combat disasters on display (Photo Feature)

Simrik Air recently conducted a heli-training and orientation for the crew, staff, and medical team to prepare them better for rushing crucial assistance during natural and man-made disasters by enhancing their skills and expertise.  Capt Siddartha Jang Gurung led a Bambi Bucket training session for helicopter pilots Capt Hare Ram Thapa and Capt Rajendra Duwal at Bojinee Dam in Nagarkot. The pilots learned the proper use and operation of this specialized tool. Simrik Air is the sole provider of this water-based firefighting service in Nepal.

Capt Siddartha Jang Gurung led a Bambi Bucket training session for helicopter pilots Capt Hare Ram Thapa and Capt Rajendra Duwal at Bojinee Dam in Nagarkot. The pilots learned the proper use and operation of this specialized tool. Simrik Air is the sole provider of this water-based firefighting service in Nepal.  In addition to Bambi Bucket training, Simrik Air also offered a variety of other realistic engagement training options such as Recco, Yak Winch, Sling operation, Long-line operation, Medical evacuation, and Management training to keep the staff up-to-date and maintain safety, efficiency, and consistency in service. Capt Bimal Sharma and Capt Bhaskar Pokharel were trained on this.

In addition to Bambi Bucket training, Simrik Air also offered a variety of other realistic engagement training options such as Recco, Yak Winch, Sling operation, Long-line operation, Medical evacuation, and Management training to keep the staff up-to-date and maintain safety, efficiency, and consistency in service. Capt Bimal Sharma and Capt Bhaskar Pokharel were trained on this.  Crew members Ang Tashi Sherpa, Tshering Dhenduk Bhote, Tshering Pandey Bhote and Sonam Bhuti were also trained during these sessions.

Crew members Ang Tashi Sherpa, Tshering Dhenduk Bhote, Tshering Pandey Bhote and Sonam Bhuti were also trained during these sessions.  These sessions were conducted under the supervision of instructor and trainer from Germany and Switzerland Bruno Jelk, Daniel Brunner and Beat Marti.

These sessions were conducted under the supervision of instructor and trainer from Germany and Switzerland Bruno Jelk, Daniel Brunner and Beat Marti.  In a country marked by difficult terrains, this kind of training is expected to be of great help in saving lives and properties during natural and manmade disasters like flooding, fires and mountaineering accidents, given that the state alone is not adequately equipped in dealing with such contingencies.

In a country marked by difficult terrains, this kind of training is expected to be of great help in saving lives and properties during natural and manmade disasters like flooding, fires and mountaineering accidents, given that the state alone is not adequately equipped in dealing with such contingencies.

Greta Rana obituary: A literary figure par excellence

Born: 1943, Yorkshire, England

Death: 25 Jan 2023, Lalitpur, Nepal

Greta Rana, a celebrated poet, novelist and translator, died on Jan 25 at the age of 80. Born in Yorkshire, UK, Rana lived most of her life in Nepal with her late husband Madhukar Shamsher Rana, a prominent economist and former finance minister. Rana was a writer of the highest class, who produced several works of fiction, poetry and other literary works. ‘Les Misérables’ by Victor Hugo, ‘Wuthering Heights’ by Emily Brontë, and ‘Great Expectations’ by Charles Dickens were some of her all-time favorite books. Among the Nepali literary figures, she admired novelist Dhruba Chandra Gautam.

In 1991, Rana won the Arnsberger Internationale Kurzprosa for her short story ‘The Hill’, which was inspired by the Godavari marble quarry. She also translated ‘Seto Bagh’, a historical novel by Diamond Shumsher. ‘Hidden Women: The Ruling Women of the Rana Dynasty’, ‘Beneath the Jacaranda’, ‘Hunger is Home’, ‘Nothing Greener’, ‘Distant Hills’, ‘Guests in this Country’, ‘Hostage’, and ‘Ghost in the Bamboo’ are some of her notable works of poetry and fiction. Rana was also a founder member of PEN Nepal and a former chair of International PEN Women Writers’ Committee.

In 2005, she was awarded the Order of the British Empire by the British government for her contributions and achievements in the literary field. Besides literary career, Rana also contributed to children’s education in Nepal. She established Shakespeare Wallahs, a theater group, to raise funds for the education of children from the poor communities.

Rana was also passionate about conserving the mountain environment and the people living there. She was active in the development work of International Center for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD), where she worked until 2004. Sharing her vision for Nepal in this paper, she had said she wanted to develop towns in the mountains where all services are available, so that our youths don’t have to labor in foreign lands.

“The Himalayas of Nepal are full of micro-climates. We have a comparative advantage as we can grow anything here. We can grow fruits and vegetables when it is off-season for them elsewhere and then export them. This will give Nepal much-needed revenue.” Rana was also an advocate of an education system that incorporated job training. “We won’t get anywhere with the outdated curricula that simply don't contribute to our society,” she told this paper.

Rana also dreamt of Nepal having enough electricity and running water for each home. She firmly believed that with proper governance, those things could be achieved within couple of decades, especially with mini and micro hydel potential in Nepal. Rana passed away while undergoing treatment for brain tumor at Nepal Mediciti Hospital in Lalitpur.