Greta Rana obituary: A literary figure par excellence

Born: 1943, Yorkshire, England

Death: 25 Jan 2023, Lalitpur, Nepal

Greta Rana, a celebrated poet, novelist and translator, died on Jan 25 at the age of 80. Born in Yorkshire, UK, Rana lived most of her life in Nepal with her late husband Madhukar Shamsher Rana, a prominent economist and former finance minister. Rana was a writer of the highest class, who produced several works of fiction, poetry and other literary works. ‘Les Misérables’ by Victor Hugo, ‘Wuthering Heights’ by Emily Brontë, and ‘Great Expectations’ by Charles Dickens were some of her all-time favorite books. Among the Nepali literary figures, she admired novelist Dhruba Chandra Gautam.

In 1991, Rana won the Arnsberger Internationale Kurzprosa for her short story ‘The Hill’, which was inspired by the Godavari marble quarry. She also translated ‘Seto Bagh’, a historical novel by Diamond Shumsher. ‘Hidden Women: The Ruling Women of the Rana Dynasty’, ‘Beneath the Jacaranda’, ‘Hunger is Home’, ‘Nothing Greener’, ‘Distant Hills’, ‘Guests in this Country’, ‘Hostage’, and ‘Ghost in the Bamboo’ are some of her notable works of poetry and fiction. Rana was also a founder member of PEN Nepal and a former chair of International PEN Women Writers’ Committee.

In 2005, she was awarded the Order of the British Empire by the British government for her contributions and achievements in the literary field. Besides literary career, Rana also contributed to children’s education in Nepal. She established Shakespeare Wallahs, a theater group, to raise funds for the education of children from the poor communities.

Rana was also passionate about conserving the mountain environment and the people living there. She was active in the development work of International Center for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD), where she worked until 2004. Sharing her vision for Nepal in this paper, she had said she wanted to develop towns in the mountains where all services are available, so that our youths don’t have to labor in foreign lands.

“The Himalayas of Nepal are full of micro-climates. We have a comparative advantage as we can grow anything here. We can grow fruits and vegetables when it is off-season for them elsewhere and then export them. This will give Nepal much-needed revenue.” Rana was also an advocate of an education system that incorporated job training. “We won’t get anywhere with the outdated curricula that simply don't contribute to our society,” she told this paper.

Rana also dreamt of Nepal having enough electricity and running water for each home. She firmly believed that with proper governance, those things could be achieved within couple of decades, especially with mini and micro hydel potential in Nepal. Rana passed away while undergoing treatment for brain tumor at Nepal Mediciti Hospital in Lalitpur.

What’s behind repeated shelving of crucial NC meet?

Nepali Congress President Sher Bahadur Deuba has postponed the party’s central committee meeting, yet again. Thursday’s move comes three days before the scheduled date for the meet. At a time of deepening dissatisfaction within the party over the leadership’s style of functioning in contravention of the party statute, this move is sure to rile the rival camp further. Deuba had postponed meets scheduled for Jan 6 and 12 also.

The party president does not want to hold the CC meet for a number of reasons. Firstly, Deuba fears he will come under criticism for failing to give continuity to the pre-poll ruling alliance. Before the 20 Nov elections, Deuba had thrown his weight behind the alliance, taking action against leaders and cadres opposing his scheme, without bothering to take the whole party into confidence.

But the pre-poll ruling alliance fell like a house of cards for want of understanding between Deuba and CPN (Maoist Center) Chair Pushpa Kamal Dahal on the issue of premiership.

Initially, the largest party in the parliament (88 seats) had wanted to lead the government. This pushed Dahal to the CPN-UML camp. With support from UML and some other fringe parties, a coalition government took shape under Dahal. Though consigned to the opposition bench, the NC was forced to vote for the government in a trust vote in the parliament. Subsequently, the party has lost important positions like the Speaker and the Deputy Speaker.

All this has many CC members miffed. Deuba does not want to face their ire, with a vote for President round the bend. A CC meet will give rivals an opportunity to target Deuba, alienating Dahal further and causing more setbacks for NC. This leaves Deuba with little choice.

Bishnu Prasad Chaudhary: Tharus have distinct identity, they are not Madhesis

The Tharu Commission is provided for in Part 27, Article 263 of the Constitution of Nepal. The Tharu Commission Act, 2017 has been enacted by the parliament incorporating topics like the qualifications of the chairperson and members of the Tharu Commission, status of vacancies, remuneration and service conditions, duties and rights. Bishnu Prasad Chaudhary was nominated the first chairperson of Tharu Commission four years ago. Pratik Ghimire of ApEx caught up with Chaudhary to know about the progress that the commission has made so far.

What are the major working areas of the Tharu Commission?

Our major work is to conduct research on the Tharu community, culture, food, language and all Tharu identity-based issues. We also research problems facing the Tharu community like health, employment and education. The commission regularly conducts awareness programs, skill- and education-based training and workshops for the welfare of the community. Moreover, we study plans and policies of the government and offer suggestions.

Does the government implement your recommendations?

I must say no. The government, to date, has not endorsed our suggestions. It has a major role to make our work effective, meaning that without coordination from the federal government, we can’t even be a proper watchdog. Everything we do, or we require (human resources and budget) to run the office is associated with the government.

For research activities, we need a huge budget, which we don’t have. For example, data are the foremost requirement for any research but due to the lack of budget, we can’t collect data on our own, so we have to rely on secondary sources. These sources are neither reliable nor accessible. We regularly recommend the government on law and policy making, but they don’t listen. This doesn’t mean these commissions should get executive powers. The duties, responsibilities and rights that the constitution provides us are enough. The problems lie with the government. It must heed our suggestions, and provide us human resources and the budget.

How is the coordination of the commission with three tiers of the government?

Though we work with all three tiers of the government, we are in touch mainly with local and federal governments. For training and workshops, we coordinate with respective local governments while for policy-making, we consult with the federal government. As we have our main office in Kathmandu and no liaison office outside, it's quite difficult to coordinate, both with the government and the people.

These commissions don’t have executive powers. In light of ongoing debates about their relevance, do we really need them?

Without these commissions, there will be an identity crisis. In the public service field, Tharu communities were included in the Madhesi cluster after the 2007 revolution. At that time, the Tharu communities had no idea about this. After coming to know about the matter, they protested which resulted in the Tharu revolution—and establishment of the Tharu Commission. The commission has outlined identity-based problems and often warned the government and concerned bodies about the consequences of ignoring them.

Thanks to this, the Tharu cluster is determined for political representation in the Election Act. The Civil Service Act has not incorporated these issues. The Madhesi Commission and the Madhesi leaders have always wanted Tharu and Muslim communities included in their cluster, but we stand firm against it. We have our own history, culture and identity. We won’t let this die down.

How often do you coordinate with other commissions?

We have met with the Madhesi Commission a couple of times for problem identification and resolution of cluster issues. But they don’t want to coordinate with us; they want us in their cluster instead. It appears like they don’t respect our identity. But they should be clear that we are not the Madhesis.

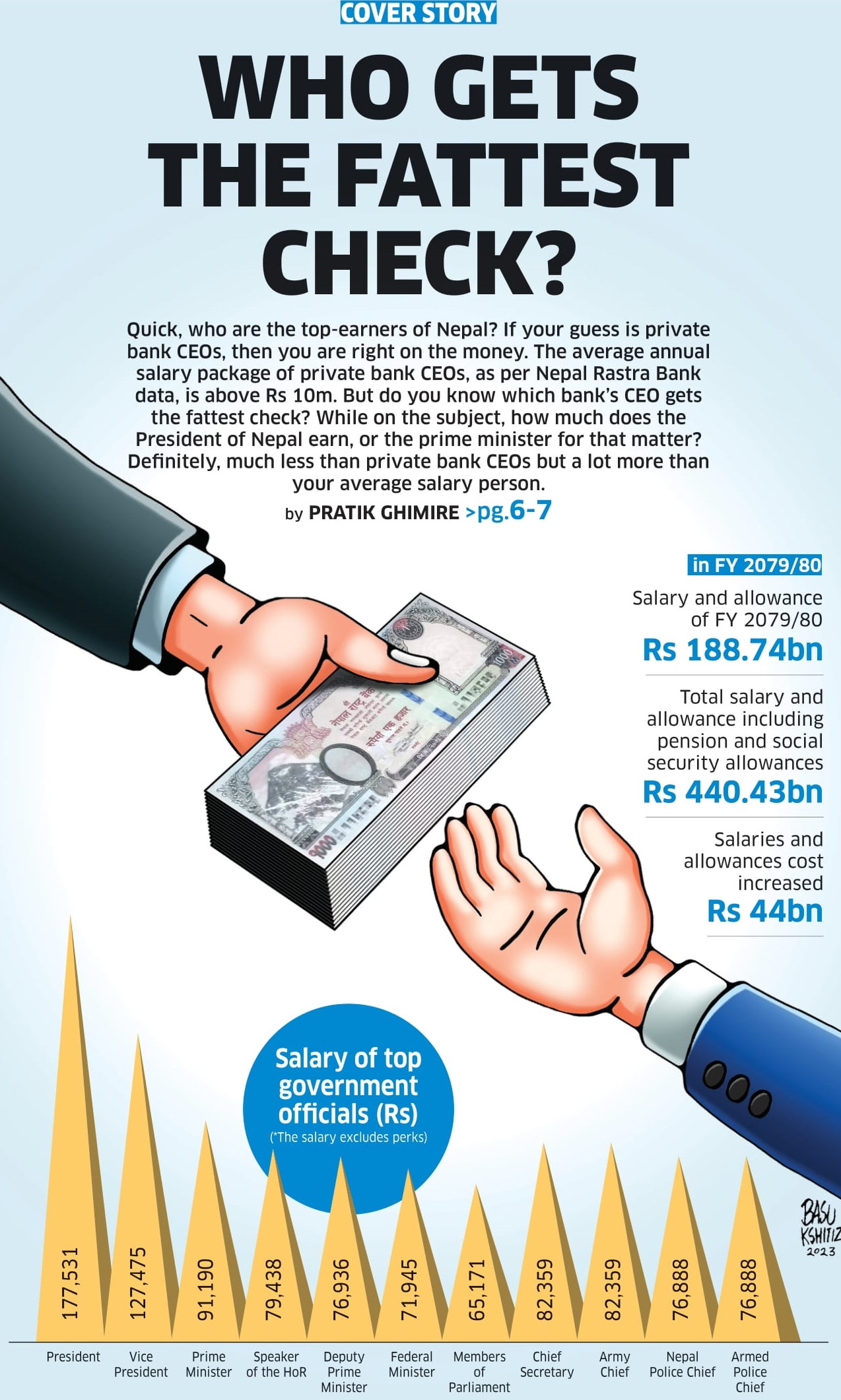

Who gets the fattest check?

Quick, who are the top-earners of Nepal? If your guess is private bank CEOs, then you are right on the money. The average annual salary package of private bank CEOs, as per Nepal Rastra Bank data, is above Rs 10m. But do you know which bank’s CEO gets the fattest check? While on the subject, how much does the President of Nepal earn, or the prime minister for that matter? Definitely, much less than private bank CEOs but a lot more than an average salary person.

Pratik Ghimire of ApEx reports on the salaries and benefits of top government officials and bank honchos.

One of the decisions of the first Cabinet meeting of the Pushpa Kamal Dahal-led government was that the prime minister and ministers will not take the 15 percent salary raise for a year in order to maintain austerity in public expenditure. The previous government led by Sher Bahadur Deuba, had increased the civil servants' salary by 15 percent in the federal budget for the fiscal year 2022/23. With the increment the cost of salaries and allowances increased by more than Rs 44bn in the current fiscal year. In line with the decision, Rs 188.74bn was allocated for salary and allowance for the running fiscal year.

Together with pension and social security allowances the allocation stood at Rs Rs 440.43bn against Rs 364.44bn of the previous fiscal year. The president, vice president, prime minister, speaker of the House of Representatives, chairman of the National Assembly, chief ministers, federal ministers, chief secretary, army chief, lawmakers, and chiefs of the Nepal Police and Armed Police Force are among the highest paid government officials in the country. While their salaries are much lower than the CEOs of private banks and companies, those holding top political and executive positions do enjoy other privileges apart from their salaries.

As per latest data, President Bidya Devi Bhandari draws a monthly salary of Rs 177,531 while Vice President Nanda Bahadur Pun takes home Rs 127,475. The prime minister gets a monthly paycheck of Rs 91,190 while the Speaker of the HoR gets Rs 79,438. Similarly, the monthly salary of the deputy prime minister is Rs 76,936 while that of ministers is Rs 71,945. Members of parliament, meanwhile, get Rs 65,171 monthly.

The Deuba-led government had decided to increase the salaries and other perks and benefits of the country’s five top officials, including the president and prime minister, as per the recommendation of the committee led by the then Secretary of the Prime Minister's Office, Lakshman Aryal. The committee's report titled 'Report on Salary, Facilities of Special Officers-2079' had proposed increasing the monthly salary of the president to Rs 250,000, the vice president to Rs 150,000, the prime minister to Rs 110,000, the speaker to 95,000 and the chairman of the National Assembly to Rs 95,000 per month. The committee had made the recommendation based on the salary increment rates of government employees in the years 2020, 2021, and 2022.

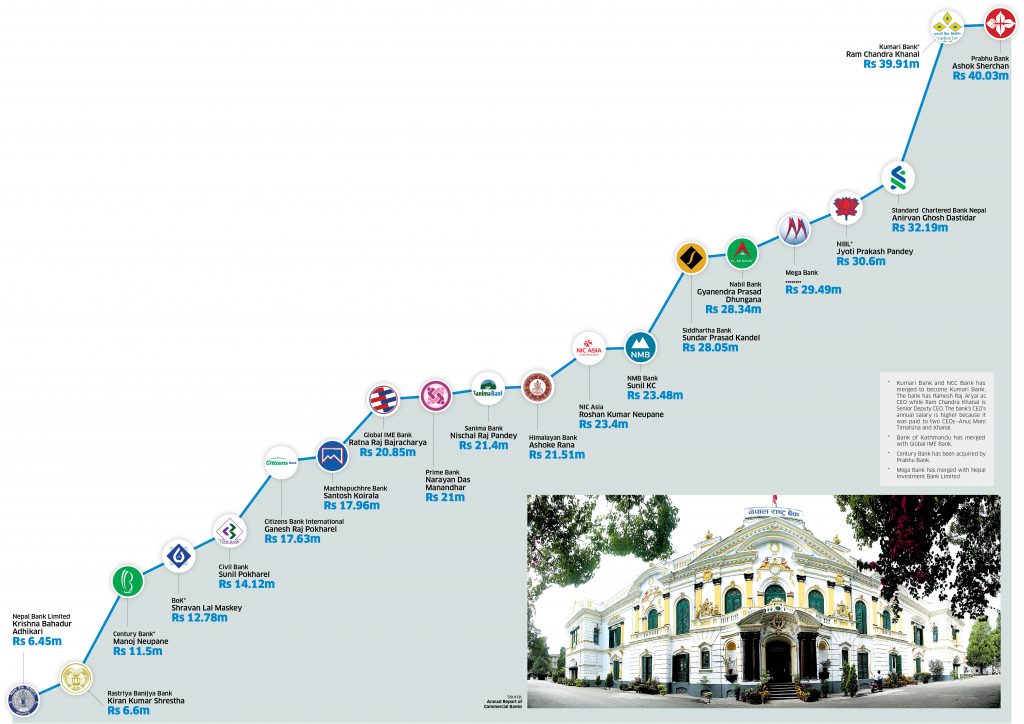

How much do the highest-paid bank CEOs get?  Banking has always been the most preferred sector for job seekers in Nepal, as it offers lucrative pay and allowance packages compared to other lines of work. The salary index that Nepal Rastra Bank (NRB) publishes every month also shows salary growth of bank employees is higher than those working in other sectors. As per the recent macroeconomic report published by the NRB, the salary index of bank and financial institute (BFI) employees increased by 25.04 percent in the first five months of the current fiscal year compared to the same period of the last fiscal year.

Banking has always been the most preferred sector for job seekers in Nepal, as it offers lucrative pay and allowance packages compared to other lines of work. The salary index that Nepal Rastra Bank (NRB) publishes every month also shows salary growth of bank employees is higher than those working in other sectors. As per the recent macroeconomic report published by the NRB, the salary index of bank and financial institute (BFI) employees increased by 25.04 percent in the first five months of the current fiscal year compared to the same period of the last fiscal year.

Apart from the monthly salary, the BFI employees also receive benefits such as accrued leave allowances, allowances, bonuses, social security benefits, and insurance facilities. They can also get loans to buy houses and cars at low-interest rates. That is why the remunerations of bank CEOs always attract a lot of public interest. The available data shows that bank CEOs are among the highest-earning professionals in the country. As per the NRB rule, a CEO can work in the same bank for two consecutive terms (eight years) only. After that, a 'cooling period' of six months is applicable if he/she wants to join another bank.

The remunerations of CEOs of government-owned banks are less than their private bank peers. The annual salary and allowances of the CEOs of government-owned Rastriya Banijya Bank (RBB), Nepal Bank Limited, and Agricultural Development Banks are around Rs 5m. Krishna Bahadur Adhikari, CEO of Nepal Bank, received Rs 5.4m in the last fiscal year. The annual salary package of Kiran Kumar Shrestha, CEO of RBB, was Rs 6.6m in FY 2021/22. Among the commercial banks, the annual remuneration packages of the CEOs of Prabhu Bank, Standard Chartered Bank Nepal, and Nepal Investment Bank Limited (NIBL) are the highest.

Each of the CEOs received annual remuneration of above Rs 30m in the last fiscal year. The average annual salary package of CEOs of private banks is above Rs 10m. In FY 2021/22, Prabhu Bank CEO Ashok Sherchan received an annual pay package of Rs 40.03m, the highest among the bank CEOs to date. In FY 2021/22, NIC Asia CEO Roshan Kumar Neupane's annual package was Rs 23.4m. NIC Asia paid Rs 18m as salary and allowances, and Rs 5.2m as a bonus to Neupane in the last fiscal year. Similarly, Siddhartha Bank paid Rs 28m to its CEO in FY 2021/22.

Himalayan Bank paid Rs 21.1m as a salary and allowance to its CEO Ashoke SJB Rana in the last fiscal year. The bank paid Rs 10.6m as salary and Rs 9.5m as allowances to Rana. Prime Commercial Bank paid annual remuneration of Rs 21m to its CEO Narayan Das Manandhar. Of the total remuneration paid to him, Rs 18m was salary and Rs 8.5m was allowance and Rs 1.4m was Dashain allowance.

Laxmi Bank CEO Ajay Bikram Shah was paid Rs 13.2m as annual remuneration in the last fiscal year. NMB Bank paid Rs 23.4m annual pay package to its CEO Sunil KC in FY 2021/22. Of the total remuneration, Rs 8.5m was allowance and Rs 5m was bonus. Nepal Investment Bank Limited (NIBL) paid an annual salary package of Rs 30.6m to its CEO Jyoti Prakash Pandey in FY 2021/22. Of the total package, Rs 16m was salary, Rs 10.7m was allowance and Rs 2.2m was Dashain allowance.

NRB Governor receives Rs 5m in remuneration

Maha Prasad Adhikari, governor of Nepal Rastra Bank, received Rs 4.90m in remuneration in the last fiscal year, of which Rs 1.41m was salary and Rs 305,000 was meeting allowance of the board of directors of the central bank. Similarly, the governor received Rs 3.18m in other allowances and facilities.

Meanwhile, NRB deputy governors Neelam Dhungana and Bam Bahadur Mishra have received Rs 4.26m and Rs 4.22m in remunerations, respectively, in the last fiscal year. As per data published by NRB, both deputy governors received Rs 1.26m in salary. Dhungana's BOD meeting allowance totaled Rs 273,000, while it was Rs 296,000 for Mishra. Meanwhile, Rs 2.71m was paid to Dhungana in other allowances and facilities which was Rs 2.63m for Mishra.

Banks paid Rs 47.17bn in salary and allowances; Rs 10.67bn paid as a bonus

The NRB data shows commercial banks' employees' expenses increased by 10.15 percent in the last fiscal year. The commercial banks operating in the country paid Rs 47.17bn as salary and allowances to their employees in FY 2021/22. Such salary and expenses stood at Rs 42.82bn in FY 2020/21. Similarly, banks also paid Rs 10.67bn as bonuses to their employees in the last fiscal year.

Dahal government faces global pressure to right war-era wrongs

With the formation of a new government under Pushpa Kamal Dahal, the international community has started showing concerns about conflict-era rights abuses. On Jan 12, Human Rights Watch, a rights body, came up with a statement urging the Dahal-led government to amend the transitional justice bill.

A new transitional justice bill, to address abuses committed during Nepal’s 1996-2006 civil war, was presented to the parliament in Aug 2022, HRW says, adding: The bill, despite significant flaws, had raised hope among the victims and their families, who have waited over 16 years for justice. The flaws include wording that makes it possible to grant amnesty for certain gross violations of human rights, crimes against humanity, and war crimes, the statement said.

In addition, verdicts from a new special court would not be subject to judicial appeal, in violation of international fair trial guarantees. The bill was neither amended nor brought to a vote before parliament was dissolved ahead of November elections, according to the statement.

Speaking with media persons on Jan 12, American Ambassador to Nepal Dean R Thompson said that the international community is keenly interested to see progress in transitional justice. “This is definitely something that I talk about with my colleagues in the international community. I hope we can see progress,” he had said: “Ruling parties in their Common Minimum Program have pledged to conclude the transitional justice process.”

Transitional justice mechanism—Truth and Reconciliation Commission and Commission of Investigation on Enforced Disappeared Persons—are without heads and other officer-bearers. The international community, however, has not cooperated with the commissions. The bottom-line of the international community is that there should be appointment in both commissions only after the amendment of laws in line with the Supreme Court verdict 2015, said former Chair of Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

Has Deuba grown too powerful for NC’s own good?

Nepali Congress President Sher Bahadur Deuba had already made up his mind to offer the party’s vote of confidence to Prime Minister Pushpa Kamal Dahal in Parliament on Tuesday. Since he holds a strong command in the NC, he was confident that the rival leaders inside the party would toe his line.

Earlier in the day, Deuba called for the party’s meeting to take a formal decision on the issue. At least five senior leaders had opposed Deuba’s plan to give Dahal the trust vote. They were in favor of the party playing the role of an opposition. But Deuba was adamant on his decision. The disagreeing leaders registered a note of dissent, but the NC leader prevailed. Deuba’s recent victory in the parliamentary party leader election has made him even stronger. Deuba’s position was particularly emboldened after senior Ram Chandra Poudel, his former rival, backed him.

Shekhar Koirala, Deuba’s only rival in the party, too, has also been taking a soft approach, because he is busy preventing the emergence of youth leaders like Gagan Kumar Thapa and Bishwa Prakash Sharma. On the vote of confidence issue too, Koirala supported Deuba’s move. While Deuba may be powerful, he has still not reached the level of being above reproach. Within the party, his leadership is facing criticism for being the cause for the breakdown in the five-party electoral alliance, which relegated the party to the opposition.

Party leaders have been demanding a meeting of the Central Committee to discuss the debacle, but Deuba has been postponing the imminent showdown. Initially, the meeting was called for Jan 6 which was later postponed to Jan 12 and to Jan 29. It is clear that Deuba wants to hold the CWC meeting once the criticism subsides. At the CWC meeting, there will be the inexorable question of why the party leadership failed to keep the electoral alliance of the five parties intact.

While Deuba has not spoken a single word since the debacle, opinions are building up within the party, which could be divided into three parts. First comes from the Deuba camp itself, which conveniently takes off the blame from the party leadership and shifts it to the entire party. Deuba’s core supporters are of the view that there was intra-party consensus that as the largest party in parliament, the NC should get both prime ministerial and presidential posts.

A leader close to Deuba told ApEx that even the leaders from the rival camp, including Koirala and Thapa, had taken a firm stance that the party should get both positions. “The party leadership took the advice and took its position with the other parties, which led to the breakdown in the alliance,” said the leader. Prakash Sharan Mahat, another leader from the Deuba camp, is also not willing to point the finger at the party president. “We have to investigate what caused this failure, but laying the blame squarely on the party president will not solve the problem,” he added.

A second school of thought is that the party leadership must admit to the failure and move on by putting a united front. For them, staying united is more important than ever. “Continuous blame-game will only weaken the party,” said CWC member Nain Singh Mahar. “The upcoming Central Working Committee meeting should give a message of unity, not of division.”

Thirdly, there are those who want Deuba to step down on moral grounds. Leaders like Gururaj Ghimire have already called for Deuba’s resignation. After the five-party alliance broke down, and the CPN (Maoist) went on to form a coalition government with the CPN-UML and other fringe parties, Ghimire said that Deuba had lost the moral ground to lead the party. He also called for a special convention of the party to elect a new leadership. There are chances that NC general secretary duo Thapa and Sharma could also demand Deuba’s resignation and call for a special convention at the CWC meeting. But with divergent opinions within the party, chances of such convention taking place are slim.

Even inside the rival camp led by Koirala, the leaders are not on the same page. Koirala in particular is not in the mood of taking a confrontational approach with Deuba. He has called for a long-overdue policy convention of the party instead. With the opinions divided regarding the breakdown of the five-party electoral alliance, the heat will definitely be on Deuba when he faces the party leaders next week.

But Deuba is not the kind of leader to fess up to his failure. He has been in a similar situation before. In 2017, when the NC faced an unprecedented electoral drubbing under his leadership, Deuba faced the firing squad and came out alive. Then, too, there were calls for his resignation.

The fact is Deuba is too powerful. His rivals in the party know this very well. Despite the major electoral loss in 2017 and the post-election fiasco this year, it is nearly impossible to remove him. The rival leaders do not have the right and the resources to rally the support of two-thirds members of the party to unseat Deuba. By postponing the CWC meeting, Deuba has bought himself the time to prepare himself. He has already started the homework on how to neutralize his detractors. Deuba knows that even some of his supporters could upbraid him for not making the effort to keep the five-party electoral alliance together.

To temper the critical views, one leader said Deuba has been meeting his core supporters and instructing them to speak in his favor at CWC meetings. The NC president wants to show that it was not him, but the CPN (Maoist Center) leader and new Prime Minister Pushpa Kamal Dahal, who committed the betrayal and broke the alliance.

Amresh Kumar Singh: Won’t join the Congress anytime soon

Though a prominent leader from the Madhes, Amresh Kumar Singh didn't get a ticket from Nepali Congress in the Nov 20 parliamentary polls. He then contested the election as an independent candidate and defeated a Congress candidate! Pratik Ghimire of ApEx talked to Singh regarding the present political situation.

Where do you see the future of the ruling coalition?

I think it will go far. During our meetings, I have felt that both KP Oli and Pushpa Kamal Dahal have realized their past mistakes and are ready to work together to ensure longevity of the ruling alliance.

Have you thought about returning to the Nepali Congress?

No. My people have given me the mandate to serve them as an independent representative. I won’t go against their will.

Where do you see the future of the Congress party?

Unless the Congress realizes its mistake and starts working for the people, they don't have a future. Commercialization has hit the party hard. The party should put an end to corruption within its fold. They are still trying to get votes by selling the name of BP Koirala, but this won’t work, I tell you. The present generation has not seen BP and they won’t be convinced. The party should work for this generation, especially for the lay individual; it won’t survive otherwise. Have you seen the party leadership visiting districts, rural areas? The party can't go places by ruling from Kathmandu. They should rather go to the masses and win the trust of the youth. The Congress needs a revolution.

Are our neighboring countries happy with the present government?

We should not think that way. For me, no foreign policy is right or wrong; it should just stick to national interest. I don't think India and China have this traditional approach to foreign policy. These days, they don't directly interfere in the internal politics of Nepal. Rather, they raise issues during bilateral dialogues. The work of the day of the government depends on how the neighboring nations deal with it.

Our geopolitical situation doesn't allow us to tilt toward any neighbor. Our foreign policy should promote economic interests like trade balance and a suitable climate for foreign investors. Politics has become a major factor hindering development and investment. How will the government act to tackle these issues? Much depends on that.

Where do you see Madhes politics now?

Madhes has a political vacuum and this is the reality. New parties have emerged, but there will be no progress in Madhes if the new ones follow the path of the old ones. Unless there is a change in political characters and political tendencies, I don’t think much will change. Political leaders have often used Madhes-based agendas to climb the political ladder but they never worked for the welfare of the people.

Madhes has many problems like unemployment, low literacy, weak economy and all but no party has ever bothered to address these problems. Madhes has an agriculture-based economy but it does not have new technology and equipment to cash in on this economy. Madhes needs a social reformer more than a political reformer.

No one willing to fix overcrowded prisons

It is said how a country treats its prisoners indicates its overall view on human rights. In Nepal, prisoners are treated in an inhuman way, often locked up in cramped spaces with little to no healthcare facilities. The Central Jail in Sundhara, Kathmandu, is a case in point. The country’s oldest and largest prison facility has an inmate capacity of 1,500, but it is currently holding 3,448 prisoners. Ishwori Prasad Pandey, the prison administrator, says there is no option to ease the problem of overcrowding in the facility.

“It is not just here. You find this problem in other prisons across the country,” he says. Being the oldest prison in the country, the Central Jail lacks proper infrastructure and facilities for its inmates. The facility has its own infirmary, with a 30-bed capacity and is looked after by six medical staff, but lacks in several other areas.

Human rights activist Charan Prasai says the government and the Department of Prison Management should look into the matter and come up with a solution. “Prisoners must have basic human rights too,” he says. “The fact is that the concerned government agencies don’t care.” According to Prasai, Nepali society by and large does not believe in granting basic human rights to someone convicted of a crime. “I still remember former Prime Minister Krishna Prasad Bhattarai saying that prisons should not have access to good facilities because many people will want to commit crime in order to live the life of prisoners,” he says. “Our government and society have the same mindset to this day.”

A study report by the National Human Rights Commission states that the majority of prison facilities are in poor physical condition. The report has highlighted that basic utilities like lighting, bathrooms, and water are unavailable in most prisons, and prisoners frequently have to sleep on the floor and eat in filthy conditions. Inadequate medical care is a serious problem in Nepal’s prisons. Sick inmates don’t get the attention they need on time. The plans governments in the past came up with to reform the prison system either remain unimplemented or incomplete.

On 3 April 2014, the then government decided to move the Central Jail to Nuwakot district. The proposed prison facility with the capacity of holding 7,000 prisoners is still under construction. Another regional prison is also being built in Jhumka, Sunsari. It is said to have a holding capacity of 3,000 inmates. It remains uncertain when these two prisons will be completed. Nepal currently has 74 prisons across the country, two each in Kathmandu and Dang.

Dhanusha, Bara, Bhaktapur, Nawalparasi (East), and Rukum (East) are the only districts that don’t have their own prisons. The total number of inmates and detainees stands at over 27,000. The framework for general prison management is provided by the Prisons Act of 1963 and the Prisons Regulations of 1964, which have been updated as necessary to reflect evolving conditions.

“While the idea of developing prisons into correctional facilities has received increasing attention in recent years, the government has yet to fully embrace the concept,” says former Nepali Police Deputy Inspector General Hemanta Malla Thakuri. A plan to set up an open prison in Banke and convert existing prisons and correctional facilities were outlined in the budget speech for the fiscal year 2022/23. Nothing has come of the plan yet. With the current state of Nepali prisons, Thakuri says it is impossible to provide decent living conditions to prisoners. “There are laws in place, but we have not implemented them.”

The Prisons Act states that in order to prohibit meetings and communication between male and female inmates, they must be housed in separate buildings or, if that is not possible, in separate areas of the same prison facility. Similarly, if inmates and detainees are housed in the same facility, they must be kept apart. Additionally, it is necessary to keep inmates and detainees under the age of 21 apart from those who are older.

Convicts participating in criminal and civil trials are also required to be housed in different parts of the prison. Ditto for prisoners who are unwell and those who have mental illnesses. “With our prison facilities overwhelmed by inmates, it is difficult to follow many of these laws,” says Thakuri. “There is also the risk of inmates forming a criminal network inside the prison.”

Overcrowded prisons also pose difficulty for the authorities to keep track of the inmates. When Sundar Harijan of Banke died under a mysterious condition at Rolpa prison on 18 May last year, it was later revealed that he had been serving the time for Bijay Bikram Shah of Surkhet. A probe committee found out that Shah, the real convict, had worked out a deal with jailers and prison guards to imprison Harijan in his stead. In the wake of the incident, the provision of issuing inmate ID cards was introduced as part of the Prison Administration Reform Plan.

However, the provision has not been fully implemented. Rights activists say it is difficult to know the real condition of Nepali prisons, as the authorities are reluctant to allow a third-party inspection. What takes place in the confines of prison, or for that matter, in police lockup almost nearly gets out. In 2021/22, four prisoners—Hakim Miyan, Durgesh Yadav, Bijaya Mahara, and Sambhu Sada—died while being held by the police.

The NHRC is still investigating the matter. Rights activists say immediate and short-term actions with defined action plans must be taken to improve the overall condition of the prison system. This entails giving the cases of those who are being held pending trial priority and transforming prisons into correctional facilities by promptly fixing and maintaining deteriorating physical structures, making suitable arrangements for sewage and water, scheduling regular health checks and medication, and assigning staff members to designated positions. It’s also critical to emphasize the placement of health workers and maintain a clean prison environment.

“Little has changed when it comes to Nepal’s prison system,” says Prasai. “We have the same old facility and the same attitude of treating our prisoners. We can only hope this will change one day.”