Football team returns with runner-up title

Nepali National football team has returned home with the runner-up title from the 13th South Asian Football Federation (SAFF) Championship held in the Maldives.

The team reached the finals for the first time in 28 years but lost to India 3-0.

The team landed at the Tribhuvan Airport on the morning of October 18. Members were welcomed by the Minister for Youth and Sports Maheshwor Gahatraj and representatives from the All Nepal Football Association (ANFA). Football lovers and supporters from all over the country, too, came to welcome and congratulate the team.

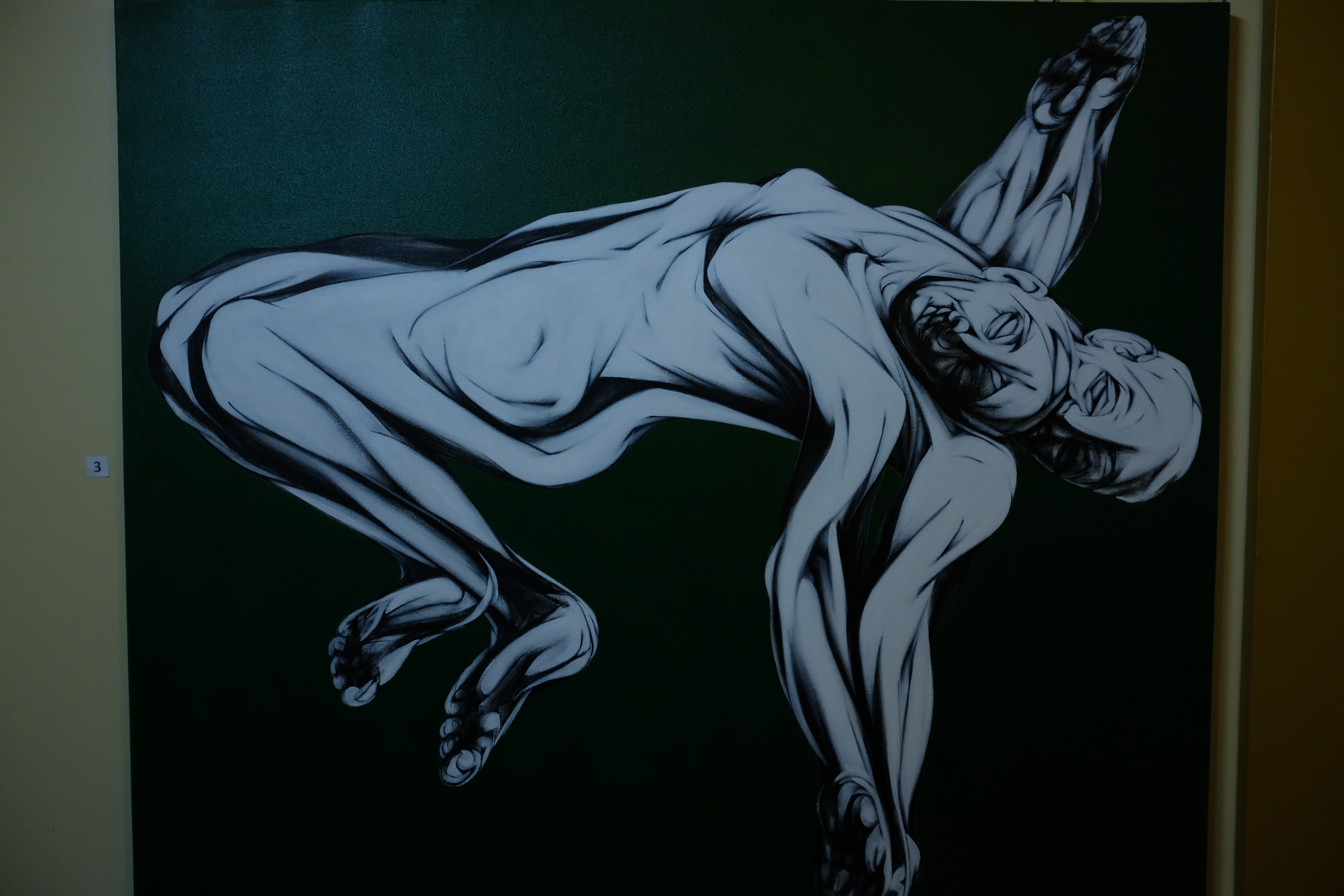

Anish Tamang: Putting his body and soul into it

You may—nay, must—have come across Anish Tamang’s extreme body painting transformation videos as you scrolled through TikTok.

An aspiring make-up artist recognized for his amazing body paintings, Tamang, who finds great joy in expressing himself this way, creates works of art with captivating details.

Growing up as a feminine boy, Tamang struggled to accept himself. Having to deal with constant bullying by his peers, he wrestled with his identity and tried to hide behind traditional gender norms. “We were only taught the stereotypical roles of a boy and a girl and, as a child, I didn’t know my being different was okay,” shares the now 27-year-old. “I tried so hard to be someone I wasn’t”.

One thing that always made him feel better, though, was make-up. After watching his mother, another make-up lover, spruce herself up, he wanted to try doing it on himself.

All his life he had dreamt of one day working as a flight attendant and he thus studied Bachelors in Hotel Management. But things didn’t exactly go as planned.

In 2012, Tamang started modeling. “In my modeling years, I would never be satisfied when other people did my make-up,” confesses Tamang. “So I always did it myself”. With no plans of taking it up professionally, he continued to get better. It was only when he did a make-up look on his sister, in 2015, that he realized that this could be a possible career path.

Also read: Souvenir’s Gallery Café: Of delectable cuisines and canvases

“Looking at my sister, I fell in love with the idea of transforming a human body and I realized that this is something I wanted to keep doing.” He thus took it up as a profession in 2018 and, today, Tamang is a full-time self-taught make-up artist and body painter.

At the start, Tamang struggled with the complications of his new job. “Earlier, I used to feel so free and paint whatever came to my mind,” he adds. “But now my expression has to incorporate people’s expectations and current trends.” Yet he still does his best possible job, both on himself as well as his clients.

In the beginning, he was only involved in facial make-up. Then he fell into depression. “I always felt so lost and everything felt rough and pointless in life. That is when body painting came to my rescue,” he says.

He remembers being struck by a dialogue from the 2019 movie ‘The Lion King’: ‘Remember who you are’. It touched him in a way nothing else had up to that time and he immediately wanted to give an expression to it.

The stars aligned, and Tamang came across a video of another makeup artist body-painting a movie scene. He knew that he had to do it too. He didn’t know how, he had never done it and he didn’t even know if he could. But after 10 hours of painting on himself, Tamang knew he had found his calling.

“At first, when I used to body-paint, it felt like I’d escaped reality. I forgot all the problems in my life. I could go on for hours and hours. And now, it has become a part of me. It reflects who I am today, what I’m going through, and how my heart is feeling.”

Also read: Behind the scenes with Fun Revolution TV

His social media presence grew with time as he started putting up content showcasing his incredible talent. More people appreciated him and he built a strong fanbase. Tamang doesn’t let negative comments online affect him much, and in fact believes Nepal will slowly come to accept all those who transcend traditional gender categories.

To support himself, Tamang also teaches make-up and at times does special-effect make-up.

It takes him nine to 13 hours to complete a body paintwork. “These past couple of years have taught me to be patient with my work, to watch myself learn and to grow with every painting I do,” he shares.

Ultimately, Tamang wants to create a space where people aren’t obliged to give up their passion to earn money. He hopes the scope of body-painting in Nepal expands as people come to realize how it is an amazing medium where art, expression, and identity complement each other.

_20211019105009.webp)

When you do something so unconventional, there are bound to be detractors. How does Tamang deal with them?

“There is always going to be someone who doesn’t like you, who you can never impress,” Tamang says. “That is when you stop caring about what they think and continue with what makes you happy.”

Souvenir’s Gallery Café: Of delectable cuisines and canvases

These days, every food place provides wireless internet to keep its visitors entertained. Some are also into creative décor. Satendra Kaji Shrestha, founder of Souvenir’s Gallery Café, has added his own twist to lure visitors.

The 58-year-old former tourist guide always wanted to work in tourism as he considers the industry a major source of the country’s income. “Art and cafés are the two strong pillars of tourism,” he says. This is why, he adds, places like Souvenir’s, an exhibition place-cum-café, could be an instant hit among tourists.

“We can make this place the busiest tourist hangout area if everyone works together,” says Shrestha about his Soltee Mode-based eatery and the surrounding area.

For this purpose, Shrestha has collaborated with five internationally recognized Nepali painters, none of whom expects much profit from the venture. We are here to start a new trend, they say.

Krishna Manandhar

One of the senior-most artists in Nepal, Manandhar completed his Bachelors in Fine Arts from Sir JJ School of Arts, Bombay in 1970. With more than 35 years of teaching under his belt, Manandhar has five solo and 25 group exhibitions to his credit.

Abstract works with natural beauty gives him great aesthetic pleasure. “In the melodious motion of life, we sometimes see sudden silences,” says Manandhar.

Sushma Rajbhandari

Rajbhandri, head of the department of painting at Lalitkala Fine Art Academy, has been in the art scene for over three decades. She has a master's degree in creative painting and has successfully organized 16 physical solos and two worldwide virtual solos.

The artist, trainer, educator, and academician, creates compositions with spiritual tones and divine figures. Her paintings of lord Ganesh are widely recognized.

Says Rajbhandari about her works: “The parallel patterned texture provides a distinct dimension, adding delicacy and mysterious directions to my painting”.

Krishna Prakash Shah

A visiting lecturer at Kunst Akademie Kalkar, Germany (2016-2018), Shah is an established contemporary abstract Nepali artist. His canvas reflects a variation of close-knit colors and its rhythmic taste.

Shah completed his Master in Fine Arts from Tribhuvan University. An art studio member of Nepal Fine Arts Academy (1997-2015), he took part in the 14th Asian Art Biennale, 2010, in Bangladesh. He has showcased his paintings at three solo exhibitions in Nepal and Europe. No one can escape the instant artistic pleasure of his works.

“Abstraction is the perfect vehicle for innovation,” says Shah.

Nem Bahadur Tamang

A PhD scholar in visual art, Tamang is also known for his abstract visual arts. Also an assistant professor at Fine Art Campus, TU, he writes poems and passionately follows philosophical works. He has four solos and hundreds of group exhibits to his name.

“I focus on the depth of materialist figures,” says Tamang, who avoids cosmetic veils. He explores the complexity of human psychology to make his painting unique and inclusive. Instead of trying to find joy in the physical world, he likes to dive into the depths of imagination to draw pearls.

Mukesh Shrestha

A gold medalist artist, Shrestha holds a Master in Fine Arts degree from Banaras Hindu University, India. He enjoys the fusion of traditional and contemporary paintings, which is a result of his socio-political inspiration. His six solos and more than 70 group exhibitions all connect structure and divinity, forcing all viewers into deep thought.

“I like to evoke feelings of love, compassion, and spirituality in my paintings,” says Shrestha whose works attempt to help spectators discover the path of love and spirituality. To add lucidity, he reduces the colors and curves–and avoids superficial decorations.

Nepali Congress boosted by influx of new blood ahead of its general convention

After much uncertainty, the preparations of Nepali Congress for its 14th general convention are finally gathering steam. The Grand Old Party has already organized ward-level conventions and municipal conventions are due soon, while the general convention is scheduled for November 25-29. The lead-up to the main event has been interesting for the party as many youngsters, including teenagers, have been elected as ward and regional level representatives. Pratik Ghimire of ApEx interviewed 10 such young regional representatives: Why join politics so young, we asked them?

Vox pop

Barsha Rani Shrestha, 18

Damak Municipality-7, Jhapa

In the ward that I live in, the presence of women in politics is virtually nil, and I wanted to do something about that. I want to represent women in my area in order to fight for their rights. Four other senior leaders also wanted the position I was eventually elected to, but they later agreed to withdraw and I became the consensus candidate. I know I have landed a prominent role and with it comes responsibility, but I am ready for the challenges ahead.

Bikal Rai, 20

Diktel Rupakot Majhuwagadhi Municipality-1, Khotang

Even during my childhood, I found politics interesting and I later decided to join student politics. To be honest, in recent times, the Nepali Congress has erred from the path envisioned by BP Koirala. This is the reason why the party has had to face many setbacks. I think this is the right time to revive Koirala’s ideology, and only the youths can do that.

Binod Raj Joshi, 21

Malikarjun Rural Municipality-8, Darchula

The prime motivation for me to get involved in mainstream politics was my passion to take up leadership roles. There can be no national transformation without politics at its core. Lately, a discourse has started on the transformation of Nepali politics, and I decided to jump in—I am not among those who wait for the opportunity. I want to fight for my spot because it helps sharpen my skills. I don’t want to be one of those ordinary youths who only abuse the system for their benefit.

Dinesh Bhatta, 21

Shikhar Municipality-9, Doti

I belong to the geographically remote far-west region. Growing up, I had limited access to books, but I used to listen to political news and interviews on the radio. They helped hone my passion for politics and ever since, I had nurtured a dream of becoming a leader to develop my region. That was also why I joined mainstream politics and the Nepali Congress.

Jem Singh Rai, 24

Halesi Tuwachung Municipality-6, Khotang

Every situation comes with its challenges. Nepal is facing a host of challenges these days, and the youths are the ones who can find solutions to these challenges. We have the responsibility to take the Nepali Congress to newer heights as the country can move ahead only when the political parties have a strong base. This is why I joined mainstream politics. I want to help with nation-building and this convention gives me that opportunity.

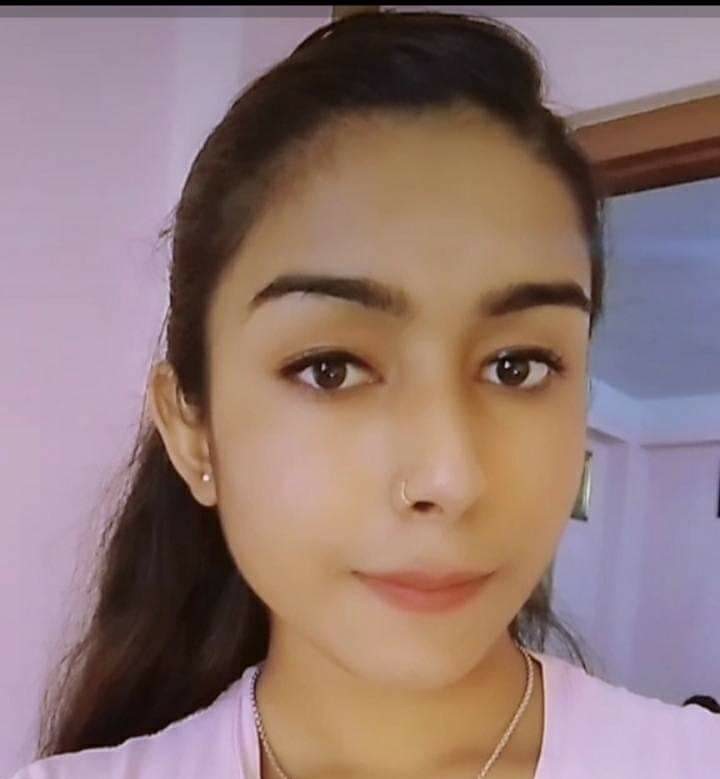

Kareena Puri, 19

Melamchi Municipality-9, Sindhupalchok

Youths are the nation’s pillars. It is the youths and their convictions that have led to substantive changes in Nepal. Unfortunately, leaders from the older generation like to cling to power. Everyone knows these politicians have lost their sense of direction. Youths like me are now in politics so that we can change the system. Nepal is a young nation and only youth leaders can understand the needs and aspirations of their fellow youths.

Padama Bhushal, 22

Galyang Municipality-4, Syangja

I have a huge passion for leadership and politics is one means to get to a leadership position and help the society. As a woman, I have faced a fair share of challenges and there was a time I thought of quitting. But if I give up, the new generation will ask me why I let the status quo continue. So I took part in the convention and secured the position through consensus. My goal is to inspire women and society.

Sachin Timalsena, 28

Yangwarak Rural Municipality-1, Panchthar

Most Nepali youths believe in democracy. Young people understand politics and know how to respect other people’s opinions. This is why youngsters are actively joining politics. The Nepali Congress is a democratic party and its convention starts from the ground level. This helps youths to grow. This is the reason I chose the Nepali Congress.

Sagun Kandel, 23

Galkot Municipality-8, Baglung

A few factors motivated me to join politics. The first is that I don’t like the old faces running the country. They have repeatedly failed the system and the country. There is no spark in their leadership. Moreover, nobody is interested in fulfilling our dream of democratic socialism.

Saraswoti GC, 20

Sunkoshi Rural Municipality-2, Sindhupalchok

If we want change, we need to come forward. We do not have educated women in politics and their participation is negligible. Being a literate female youth, I started my political career with Nepal Student Union, the student wing of Nepali Congress. But when the NSU failed to hold its convention on time, I thought of getting involved in mainstream politics.