LDCs want to graduate—but not sans a financial backstop

Nepal has set the goal of graduating from the category of least developed country (LDC) to a developing one by 2026. The deadline is just a little over four years away, and the country is badly off-track.

Economic downturns caused by the Covid-19 pandemic and more recently, the ongoing Russia-Ukraine war, have only added to the challenge of achieving the ambitious target.

Least developed countries are currently facing multiple challenges, such as ballooning trade deficits, depleting foreign currency reserves, slow industrial growth, and rising inequality. These economic challenges figured prominently at the 12th World Trade Organization’s (WTO) Ministerial Conference held in Geneva, Switzerland, from June 12-15.

The first and immediate challenge faced by the LDCs is to secure additional support from donor agencies and bilateral partners to expedite the recovery of their economies battered by the pandemic and the war in Ukraine.

To this end, officials present at the conference were of the view that WTO and other international organizations should consider an immediate package to revive the faltering economies of LDCs.

A senior WTO official said LDCs should prepare a solid and pragmatic plan to switch to the developing country category, as they lose several international facilities with the graduation. If a sound plan is not in place, the official warned, there are chances of freshly graduated countries sliding back to the LDC category.

To graduate from the LDC category is a major development success, but it comes with a host of challenges, including the loss of preferential access to lucrative markets.

So the organization’s LDC Group called on the preference-granting members to extend and gradually phase out their preferential market access schemes over a period of six to nine years. But developed countries are not ready to offer such a long transition period. China says it can provide a three-year transition, while other big powers like the US are yet to make their position on this clear.

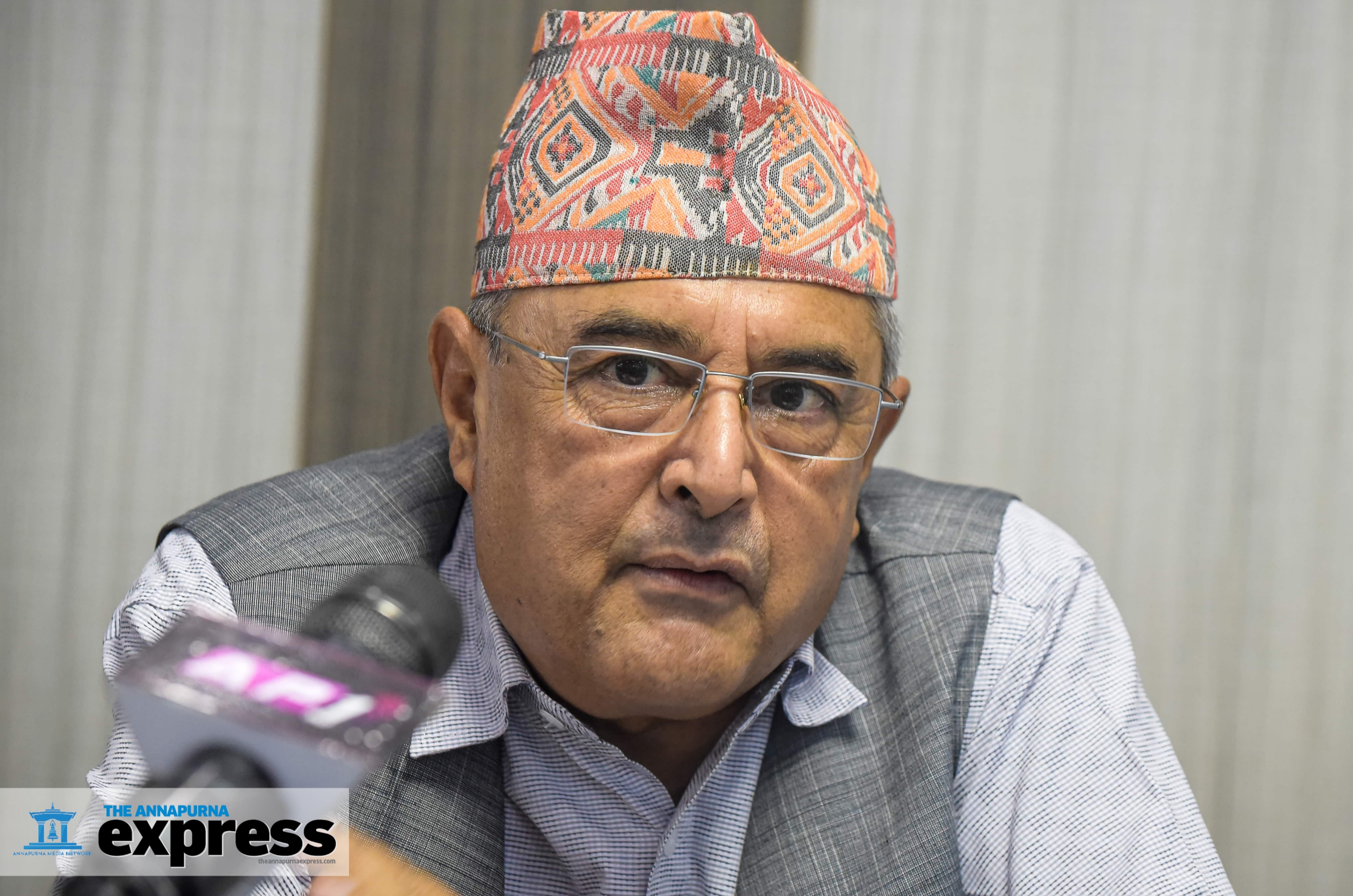

Addressing the conference, Nepal’s Minister for Commerce, Industry and Supply Dilendra Prasad Badu emphasized the need for continued international support for smooth graduation transition. He raised the issues of duty- and quota-free market access, special and differential treatments, preferential rules of origin, service waiver, aid for trade, and flexibilities in the implementation of multilateral trade rules and commitments.

The minister also told the conference that bilateral and multilateral development partners should allocate additional resources to implement the Doha Plan of Action for LDCs.

Supply-side constraints, weak productive capacity, insufficient trade infrastructures, and non-tariff barriers are some of the obstacles that keep LDCs from benefiting from the current multilateral system. The WTO’s LDC Group has been seeking international support to overcome these challenges.

High transit and transport cost of the LDCs is another constraint hindering their progress in the international trading system the WTO ensures. They have hence asked for uninterrupted, unconditional, and smooth transit rights.

The widening digital divide between rich and poor countries, which is slowing down integration in the global value chains, was also brought up during discussions.

Minister Badu told the conference that Nepal is in need of help in transferring technologies, building ICT infrastructures, and developing human resources to reduce the digital divide.

Trade ministers from Australia, Japan and Singapore acknowledged the barriers faced by developing and least developed countries seeking to benefit from the digital economy.

Issuing a joint press statement, they said the ‘E-commerce Capacity Building Framework’ will help these countries better address those barriers and enjoy the benefits of digital trade.

In order to create sound and viable technological bases, LDCs want developed countries to effectively implement the Trade-related Intellectual Property (TRIPS) agreement and give incentives to their enterprises and institutions to promote the transfer of technology.

Considering the needs of least developed countries, the WTO and the UN have signed a partnership agreement aimed at boosting the participation of LDCs in the global trading system.

The WTO is joining hands with the UN to give renewed hope to the most vulnerable group of countries to ensure that LDCs have a special place in the multilateral trading system, the WTO said in a statement.

The WTO-UN partnership aims to support LDCs with analysis of the latest trade trends, joint capacity-building and joint outreach and awareness-raising.

Over the past decade, the WTO said, its members have provided increased trade opportunities in order to expand LDC exports. It added that the WTO remains the main forum to achieve the Doha Program of Action targets in the area of trade.

There are at present 46 LDCs on the UN list, 35 of which are WTO members. LDCs want effective implementation of the WTO provisions and decisions related to special and differential treatment or exemption in favor of LDC members. They are also in need of specific technical assistance and capacity building facilities provided under the WTO system.

Members from the least developed countries at the WTO Ministerial Conference jointly urged the WTO member countries to consider their proposal without any delay. They have asked for aid and assistance for trade-related capacity building, addressing the supply-side bottlenecks, development of trade-related infrastructures, and facilitating integration of LDC economies in regional and global trade.

WTO Director-General Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala said priorities of LDCs naturally deserve particular attention. Some of them have done well enough to graduate, and are keen to smooth any bumps that might come with that step, he said.

As of 2021, 16 LDCs out of 46 are on the path to graduation. Of these, 10 are the WTO members (Angola, Bangladesh, Cambodia, Djibouti, Lao PDR, Myanmar, Nepal, Senegal, Solomon Islands and Zambia) while four (Bhutan, Comoros, Sao Tomé and Principe, and Timor-Leste) are in the process of negotiating their WTO accession. The other two LDCs are Kiribati and Tuvalu.

‘China is strengthening economic and trade cooperation with the LDCs’

Geneva. Chinese Ambassador to Geneva LI Chenggang has said that China attaches great importance to the development needs of Least Developed Countries(LDCs).

Speaking with a group of journalists from LDCs on the sidelines of the 12th Ministerial Level meeting of the World Trade Organization, the Chinese diplomat said, “In this regard, President XI Jinping proposed building community with shared future for mankind, in which case China will increase assistance to other developing countries, especially the LDCs, and do its part to narrow the north-south development gap.”

During the interactions, the Chinese envoy elaborated in detail about the support and concessions provided by China to least developed countries. He also said that China has supported the proposal made by LDCs concerning their graduation.

President Xi further proposed the Global Development Initiative, the Chinese Ambassador said, which calls for paying attention to the special needs of developing countries and supporting them, especially those vulnerable countries, through debt suspension and development assistance.

He further added that as a good true friend of the LDCs, China is actively strengthening economic and trade cooperation with the LDCs within the multilateral and bilateral frameworks.

Among them, China is continuously providing assistance to other developing countries, especially to LDCs, within its capacity. There are many examples, just to name a few, he added.

“First, China has fully implemented Decisions of all WTO Ministerial Conference on providing duty-free and quota-free treatment to the LDCs,” he said.

Insofar, China has been providing duty-free treatment to 98% of tariff items from 42 LDCs which have diplomatic relations with China, covering almost all products those countries exported to China. China is one of those developing countries that rendered duty-free treatment to the LDCs at the earliest time.

Second, China continuously expands its imports from the LDCs, the Ambassador said. Since 2008, the LDCs’ exports to China have accounted for a quarter of their total exports, making China the largest market for the LDCs consecutively for many years. The continuous expansion of China's import market, it will bring more opportunities to the LDCs’ enterprises and create more jobs for the LDCs.

Third, over the past 20 years, China spared no efforts in helping developing members, particularly the LDCs to integrate into the multilateral trading system, he added.

The LDCs and Accessions programme, established by China in 2011, has received a donation of USD 400,000 and USD 4.8 million in total so far from China. This programme has helped six LDCs accede to the WTO and has funded LDC officials to attend WTO meetings on 31 occasions.

Since 2017, China has strengthened its cooperation with the WTO under the "South-South Cooperation" Fund. China launched the "Aid for Trade" cooperation programme and helped other developing members benefit from the global value chains.

He further said, “We have been also listening attentively to the needs of LDCs facing graduation challenges and provided a three-year transition period for those who have already graduated. The duty-free treatment also applies to the graduated LDCs in the transitional period.

In the past two years, against the backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic, the LDCs have increasingly faced more challenges and their accession process has been slowed down, he said. This is definitely not conducive to the LDCs benefiting from global trade.

The Chinese envoy said that China, as always, is willing to continue to help the LDCs integrate into and benefit from economic globalization. You are messengers and bridges of friendship between China and the LDCs, and will certainly play a positive role in this regard.

Pandemic, trade, and food security take center stage at WTO conference

Geneva: World Trade Organization(WTO) members have held intensive discussions on the response to the Covid-19 pandemic including the IP response to the pandemic, and trade and food security.

The 12th Ministerial level meeting of WTO is underway in Geneva since June 12. Trade ministers of more than one hundred countries are attending the session. A Nepali delegation led by Minister for Industry, Commerce and Supplies Dilendra Badu is attending the conference.

On June 13, there were thematic sessions on pandemics and looming food crises in the world. Due to the war between Russia and Ukraine, the supply of food grains has been badly hit resulting in high inflation across the world which has taken a central stage at WTO.

On the WTO response to the pandemic, Director-General Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala noted the broad convergence on the Draft Ministerial Declaration on the WTO response to the COVID-19 pandemic and preparedness for future pandemics and on the need to resolve the five outstanding brackets, indicating areas still under discussion, in the TRIPS waiver decision.

On food security, the director-general stated that there was widespread support for the Draft Ministerial Declaration on Trade and Food Security — “almost a convergence although there are some members whose needs have to be addressed”. WTO is likely to make some declarations on looming food security on June 15.

Timur Suleimenov, First Deputy Chief of Staff of the President of Kazakhstan and MC12 Chair, said that listening to members over the past two days reaffirmed his belief that “credible MC12 outcomes are within our reach.”

“I think there is a general sense that we can actually achieve in MC12 and that it is even closer than we thought at the beginning of the Conference,” he added.

At the thematic session on the World Food Programme (WFP), according to WTO, members discussed the Draft Ministerial Decision which pledges not to impose any export prohibitions or restrictions on foodstuffs purchases for humanitarian purposes by the WFP, noting that the WFP takes procurement decisions on the basis of the principle of “do no harm” to the supplying country.

The facilitator, Betty Maina, Cabinet Secretary for Industrialization, Trade, and Enterprise Development of Kenya, said the draft decision gained massive support from almost all members with the exception of two. She said it has been a very productive meeting which underscored the commitment of WTO members to deal effectively with global crises, including the current food crisis.

She noted that she, the DG, and the agriculture negotiations chair, Ambassador Gloria Abraham Peralta of Costa Rica, will consult with these two members, with a view to achieving consensus on the text. She emphasized the consultation will not entail any change to the current draft texts.

“My intention was to get an early agreement on these texts so that we could focus on the Draft Ministerial Decision on Agriculture where more work remains to be done,” she said.

Time to demonstrate multilateralism works: WTO Director-General

Geneva(June 12)--

Director-General of World Trade Organization Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala has said that the world is grappling with uncertainty and crises on multiple fronts.

Addressing the 12th WTO Ministerial Conference that began in Geneva on June 12, she further added that the war in Ukraine and the inherent international security crisis that comes with it, the health, economic, environmental, and geopolitical crises.

This is a time to demonstrate that multilateralism works. A time to demonstrate that the WTO can deliver for the international community, and the people we serve, she said.

The meeting attended by more than 100 trade ministers is deliberating multiple issues relating to the world trade system. The Ministerial-level meeting has taken place after the five years.

The WTO director-general said while many members took some important steps forward in Buenos Aires – for example on using trade as a vehicle for women's economic empowerment – that meeting didn't really deliver.

Stressing the value of the multilateral trading system as a global public good which over the past 75 years has delivered more prosperity than every international economic order that came before it, DG Okonjo-Iweala noted that at a time when the multilateral system is seemingly fragile “this is the time to invest in it, not to retreat; this is the time to summon the much-needed political will to show that the WTO can be part of the solution to the multiple crises of the global commons we face.”

Now, more than ever, the world needs WTO members to come together and deliver, she said.

Citing WTO economists' estimations of real global GDP lowering by about 5 percent if the world economy decouples into self-contained trading blocs, she stressed the substantial costs for governments and constituents in a scenario where WTO members are unable to deliver results and where they allow or even embrace, economic and regulatory fragmentation.

To put this in perspective, the financial crisis of 2008-09 is estimated to have lowered rich countries' long-run potential output by 3.5 percent, she further added, and the 5 percent estimate represents just the start of the economic damage. Additional losses would come from reduced scale economies, transition costs for businesses and workers, disorderly resource allocation, and financial distress, she said.

Also, trade decoupling would entrench the development setbacks caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, making it much harder for poor countries to catch up with richer ones. “This would be a world of diminished opportunities, even greater political anger and social unrest, and intense migratory pressures as people leave in search of better lives elsewhere,” she added.

Various thematic sessions will take place during the Ministerial Conference to respond to ongoing emergencies, particularly the COVID-19 pandemic and the food crisis. Ministers will also have the opportunity to engage in other thematic sessions on fisheries, agriculture, WTO reform, and the e-commerce work program and moratorium.

In the WTO meeting, Nepal calls for bridging the digital divide

Geneva: Minister for Industry, Commerce, and Supplies Dilendra Prasad Badu has said that Least Developed Countries(LDCs) have been facing multiple challenges in their process of socio-economic development.

Addressing the LDC Ministerial Meeting in Geneva on June 12, he said that supply-side capacity constraints, low level of productive capacity, inadequate investment, insufficient trade infrastructures, and digital divide among and within the countries are some of the challenges.

He further stated that the non-tariff barrier, among others, has been posing challenges in benefiting from the multilateral trading system. Furthermore, LDCs are in dire need of bridging the digital divide to participate in and benefit from e-commerce and digital economy in the changing global context, he said.

Badu is in Geneva to attend the 12th Ministerial Level meeting of the World Trade Organization which began on June 12. The three-day summit will deliberate on various global trade issues. He further added that the meeting will be an opportunity to build our common position and make collective voices heard and addressed in the areas of our interest and priority.

Least developed countries are pushing for preferential rules of origins, service waiver, duty-free and quota-free market access, and flexibilities in the broader areas of agriculture, and fisheries, and supporting the recovery from the pandemic. Similarly, the reformation of WTO is another priority agenda of LDC.

12th WTO Ministerial Meeting commences today, Minister Badu leads the Nepali delegation

Geneva, Switzerland: The 12th Ministerial Conference(MCC12) of the World Trade Organization commenced in Geneva on Sunday.

Trade ministers from across the world are participating in the meeting to review the functioning of the multilateral trading system, make general statements and take action on the future work of the WTO.

The Conference is co-hosted by Kazakhstan and chaired by Timur Suleimenov, Deputy Chief of Staff of Kazakhstan's President. Kazakhstan was originally scheduled to host MC12 in June 2020 but the conference was postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The meeting of the global body will discuss WTO’s response to the pandemic, fisheries subsidies negotiations, and agriculture issues and implications of the Russia-Ukraine war on the world economy.

The least developing countries including Nepal will raise the hosts of the agenda collectively. WTO Director-General, Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, and Sandagdorj Erdenebileg of the UN High Representative for Least-Developed Countries signed a partnership agreement on June 11 in Geneva aimed at strengthening cooperation to boost the participation of least-developed countries in the global trading system.

DG Okonjo-Iweala said on the eve of MC12, we are joining hands with the UN to give renewed hope to the most vulnerable group of countries of the international community – the LDCs. … LDCs have a special place in the multilateral trading system.

He said: “Over the last decade, our members have provided increased trade opportunities to expand LDC exports and the WTO remains the main forum to achieve the Doha Programme of Action targets in the area of trade."

Erdenebileg, Chief of Policy Development, Coordination, Monitoring and Reporting Service at the Office of the High Representative for the Least Developed Countries, Landlocked Developing Countries and Small Island Developing States (UN-OHRLLS), said that improved trading situation for vulnerable countries has the potential to transform millions of lives through better jobs and stronger economies.

He said: “That is why trade is an essential element of the Doha Programme of Action for LDCs for the decade 2022-2031. With this renewed commitment between the WTO and UN-OHRLLS, the vital trade targets in the new Programme come closer within reach."

WTO Deputy Director-General Xiangchen Zhang said, “It is a historic moment. We have always worked closely with the United Nations, and today we are bringing our cooperation in support of trade development in LDCs to the next level.”

“Integrating least-developed countries into global trade is our institutional priority. And it is our shared responsibility to make sure that the opportunities offered by the global trading system reach the most vulnerable, those who need them most,” he added.

Ali Djadda Kampard, Trade Minister of Chad and Coordinator of the WTO's LDC Group, said that this partnership marks an important milestone as the international community is joining hands to help us boost our participation in global trade. He added that the start of MC12 tomorrow will be a defining moment for the entire membership.

That's why the LDC Group has been actively engaging in the work of the WTO and we remain committed to ensuring results at MC12. A success at MC12 will set us on the right path towards reinvigorating the WTO and realizing our broader development objectives, he added. There are at present 46 LDCs on the United Nations list, 35 of which are members of the WTO. Eight LDCs are in the process of joining the WTO. They are Bhutan, Comoros, Ethiopia, Sao Tome and Principe, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan and Timor-Leste.

Nepal is one of the leading countries to take the membership in WTO and is actively participating in the WTO mechanisms and dialogues. Nepali delegation led by Minister for Industry, Commerce, and Supplies Dilendra Prasad Badu is scheduled to attend the meeting. Minister Badu is accompanied by secretary Ganesh Prasad Pandeya and other high-level government officials. Minister Badu is scheduled to address the meeting.

ApEx Roundtable: The energy vision Nepal needs

ApEx is beginning a 10-part InDepth series titled ‘Nepal’s Energy Myopia’ starting with a roundtable on the issue this week. The larger goal of the series is to take a deep dive into Nepal’s energy sector and unearth the opportunities and challenges and to question assumptions. For the roundtable, we welcomed five guests with expertise in different aspects of energy production and consumption to share their views on the series title.

Deepak Gyawali, Ex-Minister of Water Resources

During the Panchayat regime, there used to be proper planning and sound vision for the energy sector. There was a sound projection of how our demand increases with time. Such planning and projection works are rather haphazard these days. There is no study involved.

The role of the private firms and foreign investors in Nepal’s energy sector increased significantly after the 1990s. Energy development licenses were issued to them willy-nilly, without carefully studying their projects and conditions.

Our per capita energy-consumption of around 300 units is the lowest in South Asia. This means we will need a lot of energy in the coming days. We have to switch to clean energy sources for cooking and transport, which means more hydropower. This cannot be achieved without the right vision. The fact is that the vision we had during the Panchayat period was scrapped after the restoration of democracy.

When it comes to investing in hydropower, we should concentrate on Nepali investors. Foreign investors seek more guarantees, want to put more risks on the government, and take home more profit. We must ask ourselves whether Nepal is really benefiting from their investment in hydropower. Existing policies make electricity more expensive, not cheaper.

The private sector should also introspect: does it seek to make profit by selling electricity after project completion or during the construction phase itself?

We have some targets in the energy sector but they are fundamentally wrong, with the focus on the sale of electric vehicles and other things. We are not focusing on what amount of fossil fuel we want to displace through such measures. In the past 14 years, we have failed to introduce the amended Electricity Act or to create a basic framework on how federal, provincial, and local governments should work in the energy sector. The entire sector is a mess. There are many areas where we can use clean energy including the ropeway, which consumes less energy than other means of transport. But we have not taken any initiative towards this end.

Bhushan Tuladhar, Clean energy campaigner

Certain clean energy targets have been fixed in Nepal, which is a positive thing. For example, Bagmati province has vowed to completely switch to electric vehicles by 2028 in its five-year plan. Likewise, the Ministry of Energy has set some targets in its white paper on the much-needed transition from traditional to clean energy. The Nationally Determined Contribution prepared by the government has pledged a net-zero energy system by 2045. There have been some serious studies while fixing these targets. But to achieve these goals, Nepal needs a clear path, which is missing.

For example, we have pledged that 25 percent of the vehicle sales in 2025 will be electric. But we lack a blueprint for this. In the absence of a clear roadmap, inconsistent policies and provisions appear in the annual budget, creating confusion.

Vague policies also discourage the private sector from investing. There is no clarity in our long-term plan on hitting targets in transport, cooking, and other sectors. What we need is a continuous campaign on the switch to clean energy. All state mechanisms, particularly local governments, must be mobilized in this, backed by a national commitment and of course a clear roadmap.

Our constitution mentions a clean environment as a fundamental right of citizens. But international studies show that every year approximately 42,000 Nepalis die from air pollution. There is a need for a revolution in our cooking system. Instead of exporting electricity to India, we must utilize it in cooking. About 67 percent of Nepalis still use the smoky biomass to cook. We need to launch a special campaign to switch to clean energy in our kitchens.

Madhusudhan Adhikari, Executive Director, Alternative Energy Promotion Center

There is a misconception in Nepal that energy means electricity. The contribution of electricity in our energy mix is less than 10 percent. In other words, when we discuss energy in Nepal, we are debating on that 10 percent. We are not sufficiently utilizing modern and clean energy. We have the Energy Ministry, which functions more like a hydroelectricity ministry. This means there is no clarity of vision. We are investing our time, energy, and mind only in hydropower. We have to look at other sources of energy as well. Recent technologies are focused on other energy sources besides hydropower. So, in the future, hydropower could become the most expensive kind of energy.

There are also questions over whether our rivers are fit for hydroelectricity, given our problems with floods, landslides and other natural disasters. Even in hydropower, we are focusing on the run-of-the-river projects, with no attention being paid in building storage projects. Similarly, Nepal Electricity Authority is just focusing on power import and export. There are also many flawed provisions in our energy policy and our understanding of energy consumption is all wrong.

Our main target at this point is to lower fossil fuel imports. But we lack dedicated institutions and targeted effort to switch from conventional to clean energy. To check chronic pollution, electric cars should be made mandatory in Kathmandu after certain years.

High cost of production is a big barrier to the growth of Nepal’s energy sector. We should have a policy to decrease the cost of energy production.

Prakash Chandra Dulal, Executive Committee Member, Independent Power Producers’ Association, Nepal

The new laws formulated after the restoration of democracy in 1990 guaranteed the private sector’s role in the energy sector. Nepal has some plans to develop the sector. For instance, the hydropower strategy promulgated in 2002 talks about the production of cheap electricity and encourages exports. Similarly, the document talks about the private sector’s role in hydropower development. We are not completely private entities but operating under the BOOT (build, own, operate, and transfer) model. The law talks about providing various facilities to hydropower projects. But then we have failed to build projects at low cost and to export electricity. Policy inconsistencies caused by frequent government changes is part of the problem.

The 15th plan prepared by the National Planning Commission talks about rapid production of hydroelectricity to boost the country’s energy sector and decrease the import of fossil fuels. Our policies are good; the problem is in implementation. Frequent government changes and with them a change of direction are a big impediment. Clearly, there is a need for the upgradation of the electricity supply system to encourage electricity-use in cooking. The federal, provincial, and local governments should come up with a clear plan on this.

For instance, municipalities and rural municipalities could declare themselves free from LPG gas and fully switch to electricity. To do so, all three levels of government should provide subsidies. With proper planning, local governments can implement this scheme within five years.

Sushil Pokhrel, Managing Director, Hydro Village Pvt Ltd

One-fifth of the world’s energy comes from hydropower. It has played a big role in the growth of countries like Bhutan, Norway, Canada, and the US. They are role models for us. Many countries have undergone economic revolutions through hydropower, so it is not wrong to advocate for it here in Nepal as well. The private sector has a high potential in hydropower. We have invested trillions of rupees. Scores of small and big hydropower projects are currently underway. With an integrated legislative framework or a one-door policy, there is no doubt we could have attracted more investment in hydropower.

But investing in Nepal’s hydropower projects is not enough. Foreign investment is low because of some flawed policies, for instance our failure to offer foreign investors an exit strategy. Established global companies are not investing in Nepal’s energy sector due to the country’s murky policies and regulations. If we fail to ensure minimum requirements, it will be difficult to attract investors. The hydropower sector has contributed a lot to Nepal’s social and economic transformation.

Power production is expensive due to lack of basic infrastructure, which is the government’s responsibility to build. We have to invest energy and resources to build infrastructure. Likewise, our notorious red-tapism scares away prospective investors. Investment process should be made clear and free of any ambiguity.

Another important issue is an investment-friendly climate. Nepal is not the only lucrative country for hydro-investment. We have to fix our issues to encourage more investment. After all, it is not just big businesspersons and investors who have stakes in hydropower projects. Even those of more limited means have a direct sake in it.

Haribol Gajurel: China always in favor of left unity in Nepal

The CPN (Maoist Center) won 122 mayors and municipal chiefs in the May 13 local elections–16 more than its 2017 tally. The party had contested the elections as part of a five-party alliance alongside the Nepali Congress, CPN (Unified Socialist), Janata Samajbadi Party, and Rastriya Janamorcha. The primary objective of this alliance was to mount a challenge against the CPN-UML with its formidable organizational strength.

While the Congress emerged as the largest party, the second spot went to the UML. The Maoist Center came a distant third. Whatever the election outcome, top Maoists leaders are of the view that the current five-party alliance should be continued until the parliamentary elections.

At the same time, talks about a left alliance, particularly between the UML and Maoists, do not die down. In fact, there is a strong sentiment among the second-rung leaders of both the Maoist Center and UML in favor of a left alliance.

In this context, Kamal Dev Bhattarai of ApEx talked to senior Maoist leader and party chief Pushpa Kamal Dahal’s close confidant Haribol Gajurel.

How do you evaluate the party’s performance in local elections?

The five-party alliance was formed to fight the authoritarian bent of the UML, whose leader tried twice to dissolve a democratically elected parliament. Broadly, the alliance has been successful. The local election was a battle between progressive and regressive forces. The regressive force has been weakened. The Maoists had expected to win around 150 seats but then the alliance didn’t work as planned in some places.

Will the current alliance endure until the parliamentary elections?

Regressive elements are trying to undermine the republic and the federal setup. So the continuity of the current left-democratic alliance is necessary in order to rout them. The five parties are in discussion on how to make the alliance even more fruitful in the parliamentary elections.

There are rumors of Maoist Chairman Dahal being offered the post of prime minister if he agrees to a left alliance?

These rumors are aimed at confusing the people. The party’s rank and file is unhappy with the leadership of KP Oli who failed to keep the erstwhile Nepal Communist Party united. As a result, the previous communist government could not stay in power for the full five years. It is also important to consider that Oli’s UML faced a defeat in the recent local-level elections.

So the offer of premiership to the Maoist party is nothing more than a UML ruse to neutralize the growing resentment within the UML party and divert attention of party leaders and cadres.

So you then see no chances of a left alliance?

Personally, I don’t, at least not until Oli abandons his regressive and authoritarian bent. Oli has assigned some of his leaders to convince the Maoist party on a left alliance. But there hasn’t been any progress. Right now, the Maoist Center doesn’t see a solid basis for such an alliance.

But this is not to say that there aren’t leaders inside the Maoist party or the UML who genuinely believe in the sanctity of the left alliance.

What about reports about China again pressing left parties to come together?

China is always in favor of left unity in Nepal. By China, I mean the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), not the Chinese government. It is no secret that the CCP wants to see the left forces of Kathmandu working together.