Energy: Can Nepal reliably reduce fuel imports?

Nepal urgently needs to cut down on the import of fossil fuels from India to check the rapid depletion of its foreign currency reserves and thereby forestall an economic crisis. Fuel accounts for 14.1 percent of Nepal’s imports, and reducing its import will help the country save its foreign currencies and to minimize the trade imbalance with India.

Replacing the traditional sources of energy with cleaner ones is also an imperative in order to curb the worsening air pollution and combat climate change.

On paper, import reduction is a major government priority but in practice, it is just the opposite. Our import continues to balloon by the day due to poor implementation of policies.

Nepal’s import-reliant economy is unsustainable, particularly when oil prices are skyrocketing and global supply chains have been disrupted by the Russia-Ukraine war.

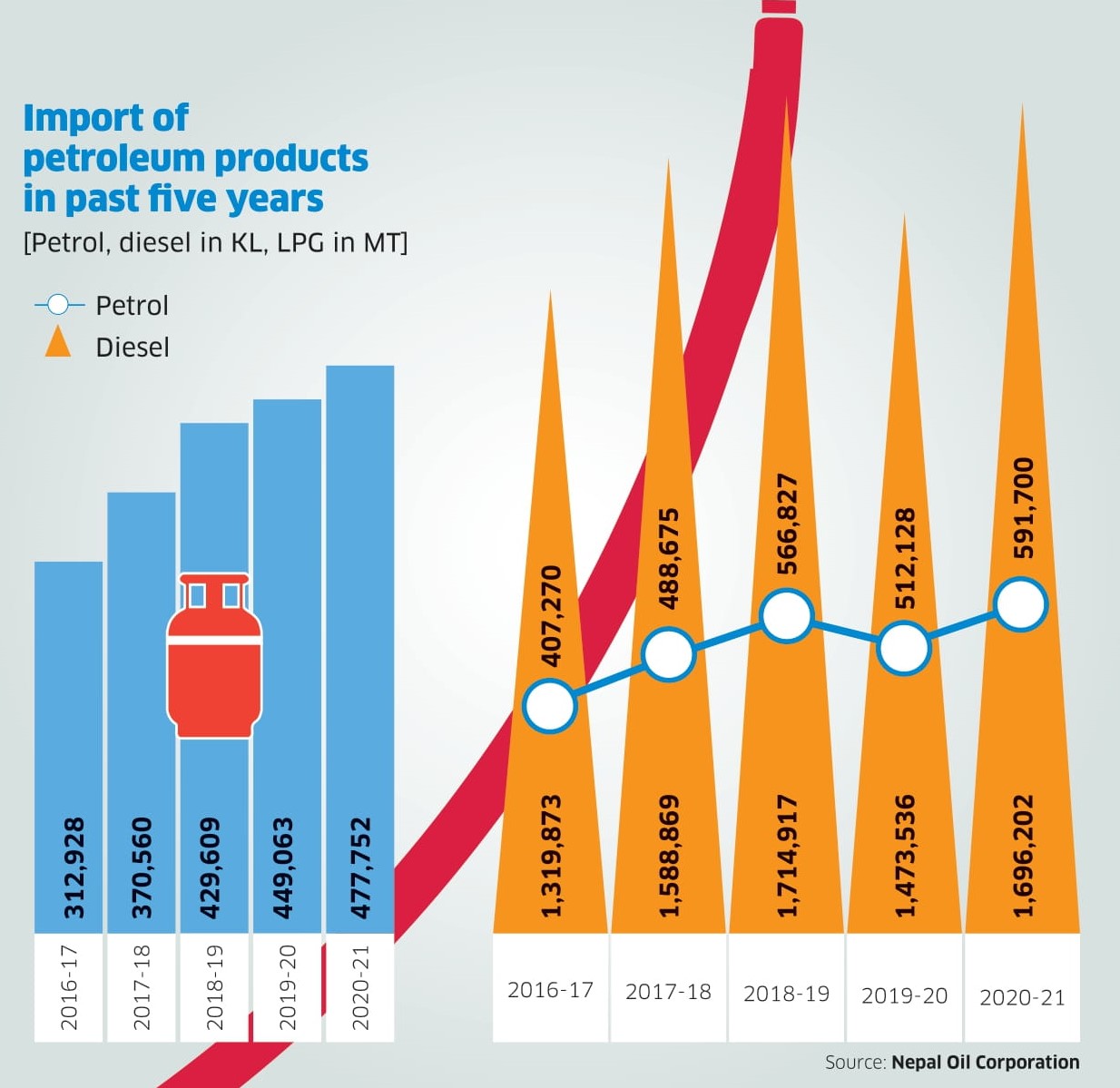

Government figures suggest significant import reduction is unlikely in the near future. According to the Economic Survey published by the Ministry of Finance (2020-2021), among the petroleum products, diesel is our chief import. In the fiscal year 2019/20, diesel made for 57 percent of the import-volume followed by petrol at 20 percent, and LPG at 17 percent. Likewise, aviation fuel made for five percent of the mix while kerosene made for a percent.

Meanwhile, the import of LPG is also increasing as gas stoves rapidly displace biomass and other traditional sources in rural kitchens. According to Nepal Oil Corporation, in the past two decades, LPG imports have jumped by 2,466 percent.

It is not just fossil fuels Nepal imports from India but also half of the total electricity it consumes during the dry season (the country also exports its surplus energy to India during summer).

Nepal currently produces 2,200MW of hydro-electricity, and plans on ramping up production to 10,000MW over the next decade. But during the dry season, our hydropower stations generate only a third of the 2,200 MW while the peak demand is around 1,700 MW. Nepal then has to import around 800 MW from India.

“With some hydropower projects close to competition, there is a hope that Nepal can stop importing electricity even in the dry season. But this could take three to four years,” says Sushil Pokhrel, a hydropower expert and the managing director of Hydro Village Pvt Ltd, a consulting company.

According to Energy Minister Pampha Bhusal, 94 percent of Nepali people have access to electricity but our per capita electricity consumption is just around 300 units a year, which is the lowest in South Asia.

Bhushal is hopeful that Nepal can produce an additional 1,000 MW of electricity within the next couple of years.

Producing more electricity is one thing. But will the produced power be optimally used? And can it replace fossil fuels, so that we can reduce our import of petroleum products?

Energy experts say extreme situations demand extreme measures.

First, they say, the government should promote the use of electric vehicles (EVs) to use up all the surplus hydroelectricity. They advise all local governments to take such measures.

The number of private electric cars is increasing, which is a good start. Greater use of EVs in public offices would be a good second step.

In its policy document, the Energy Ministry says 25 percent of all private passenger vehicle sales, including two-wheelers, will be electric by 2025. It also aims to push the number of four-wheel public vehicles (besides electric rickshaws and tempos) to 20 percent.

If this target is achieved, it would decrease Nepal’s fossil fuel imports by 9 percent, a study by the ministry shows.

Experts also suggest adopting electric stoves in our kitchens. These stoves are 60 percent cheaper to buy and operate than LPG ones.

Environmentalist Bhushan Tuladhar advises launching a special campaign to motivate people to switch to electric stoves.

“Instead of exporting electricity to India, we must utilize it in cooking. Around 67 percent of Nepalis still use the smoky biomass to cook. We need to launch a special campaign to switch to clean energy in our kitchens,” he says.

Tuladhar believes local governments have a big role to play in such campaigns.

Nepal has so far earned $25m from carbon trade and this income has been invested in alternative energy. Nepal’s Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) submitted at the United Nations pledges the use of electric stoves as their primary mode of cooking by 25 percent Nepali households by 2030. Similarly, it aims to install 500,000 improved cooking stoves in rural areas by 2025, besides also adding 200,000 household biogas plants and 500 large-scale biogas plants.

There are challenges to transitioning into electric cooking though, such as erratic electricity supply and lack of incentives for those who want to switch.

Pokhrel, of Hydro Village, says oversupply of electricity is damaging transformers and wires in some places, discouraging people from using more of it. Then there is the issue of power cuts.

“People have taken to LGP for cooking purposes as it can be stored and used as and when needed. In the case of electricity, there is no way to ensure its round-the-clock availability,” he says.

Nepal also imports some coal from India, but the exact data is not available.

Deepak Gyawali, former water resource minister, says coal can be produced even in Nepal and there is no need to import it.

“There are legal hurdles to producing commercial coal. But if we can somehow legalize coal production, we can reduce our import bill,” he says.

To cut the consumption of petroleum products, the former minister also suggests a ropeway system for goods transport.

“Right now we are using a transport system that is heavily reliant on petrol and diesel. But we can easily install ropeways and operate them with locally produced electricity,” he adds.

Wind is another source of clean energy but there hasn’t been much study on it in Nepal. Some energy experts reckon Nepal cannot produce enough wind energy to make a significant dent on our fuel import.

There is a hope for solar energy though. The Alternative Energy Promotion Center is taking various initiatives to promote solar and other alternative energy sources.

Nepal right now generates 34 MW electricity from small and micro hydropower projects and 38 MW from solar and wind sources.

Solar could be an alternative in geographically challenged areas where it is difficult to build transmission lines.

Nepal also has international climate obligations to meet as well. The country aims to reach net-zero emissions by 2045 and to this end, it has pledged to cover 15 percent of the total energy demand through clean energy sources.

To achieve this target, drastic and immediate measures are needed to promote homegrown clean energy.

“We cannot completely displace fossil fuels as there are certain areas where we have to continue to use them. But we can substantially decrease their consumption with the right policies and their strict implementation,” says Gyawali, the former water resources minister.

Dr Uma Maheswaran: The Padma Bridge paves the way for Trans-Asian Railway Network

On June 25, Bangladeshi Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina inaugurated the Padma Bridge, a 6.15-km multipurpose bridge over the Padma River. The country’s largest-ever infrastructure project, completed at $3.5bn, was built with internal resources and is the new symbol of Bangla national pride. Australia’s Snowy Mountain Engineering Corporation (SMEC) Holdings had played the roles of consultants and overseers of the mega-project. Kamal Dev Bhattarai of ApEx talked to Uma Maheswaran, chief operating officer of SMEC.

What is the significance of the Padma Bridge?

The Padma Bridge is the largest and one of the most ambitious mega infrastructure projects in Bangladesh’s history. It establishes direct railroad connectivity across the mighty Padma River, enhancing the connectivity of southwestern cities. SMEC and our local subsidiary ACE played crucial roles in the Padma Bridge project from the design and feasibility stage to implementation.

SMEC and ACE were part of the design and feasibility study back in 2009. Since 2014, ACE along with a consortium of Korea Expressway Corporation have been supervising construction. The Padma Multipurpose Bridge Project is a symbol of national pride for Bangladesh and SMEC-ACE is honored to be a part of this project.

How can it contribute to regional connectivity?

Padma Bridge is part of Trans-Asian Railway Network, which will contribute to greater connectivity and trade among Asian countries. The bridge will also pave the way for creating a new route in the network.

What were the key challenges you faced while working on this project?

The Covid-19 outbreak posed a huge challenge in execution and procurement. There were several technical challenges as well, including the high scour in the river. The construction of 3m-diameter steel tubular raking piles, which had to be up to 125 meters long, are the largest of their kind in the world, and the task was quite difficult. Special heavy hydraulic hammers had to be procured.

How was the fund managed? Who were the key financers?

The Government of Bangladesh solely financed the project. The total project cost BDT 301,930 million ($3.5bn), with the state-owned Agrani Bank Limited providing the financial backup for bridge construction.

What lessons can other countries of South Asia learn from this, as they struggle with their own mega projects?

There are several key stakeholders who work together on the single goal of making a mega-infrastructure project successful. Our client Bangladesh Bridge Authority (BBA) played a significant role in managing all stakeholders effectively, and in addition, there was strong monitoring from the government’s Cabinet team led by the prime minister. Even during Covid-19 pandemic, the whole team stayed inside the project facility for two years without taking a leave. This kind of strong commitment of each individual involved is what it takes to make mega-projects like Padma Bridge a success.

Deuba’s knotty US visit

This is not an easy time for Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba to plan an international trip. The country is only months away from federal and provincial elections. The Nepali Congress president is under immense pressure both from inside his own party as well as from coalition partners to work out a viable seat-sharing formula for the polls. His finance minister is under parliamentary investigation for allegedly benefitting vested interests in the new budget. Some suspect Deuba too could be dragged into the ‘CCTV-gate’. Meanwhile, he is under intense scrutiny of China, a close neighbor, for supposedly doing American bidding.

Amid such turbulent political climate and right on the eve of big elections, Deuba would not want to ink something remotely controversial with the Americans. In fact, he has already vowed to opt out of the American State Partnership Program (SPP), which has of late come into controversy in Nepal for its links to the anti-China Indo-Pacific Strategy (IPS). Preparations for Deuba’s visit were in full swing until the SPP controversy erupted. Nepal’s decision to stay out of the SPP has added to confusion around the visit’s timing and agenda.

Dinesh Bhattarai, a foreign affairs advisor to two Nepali prime ministers, sees the visit as a wonderful opportunity to “to brief the Americans about Nepal’s position on the SPP, which will help build better understanding between the two sides”. Deuba could also use the visit to make a case for duty-free access to Nepali goods in the American markets. Others suggest he make a case for more leadership roles for Nepalis in UN peacekeeping missions. The million-dollar question is: Will the Americans even be willing to listen if Deuba tells them that his country just cannot accept the SPP, the fulcrum of recent Nepal-China engagement?

When is Deuba going to the US?

Ever since Nepal’s parliament endorsed the $500 million American Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) compact in February, there has been a talk about Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba visiting the US. But authorities are tight-lipped about the dates and possible agendas of the visit. Foreign Ministry officials will only say that preparations are underway. The US side too has been quiet.

A high-level source at the Prime Minister’s Office tells ApEx that Deuba will definitely visit the US and the two sides are in talks to finalize the dates, most likely in the second week of August.

The exact dates and agenda will be finalized next week, says the source.

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs also expects the visit to take place soon. Sewa Lamsal, the ministry spokesperson, says the dates and the agendas will be made public ‘at an appropriate time.’ No confirmation could be secured from the Nepali Embassy in Washington, although Ambassador Sridhar Khatri has of late been meeting various high-level US officials.

Deuba’s imminent US visit is being keenly watched, as it is taking place against the backdrop of Nepal’s recent decision to pull out of America’s State Partnership Program, the ongoing Russia-Ukraine war, and the intensifying Washington-Beijing rivalry.

As this year also marks the 75th anniversary of Nepal-US diplomatic relations, high-level exchanges of visits are expected. In recent months, there has already been a series of high-level visits from the US and a few from Nepal.

Deuba’s will be the first prime ministerial-level official visit to the US in two decades. Incidentally, it was Deuba who made the last official visit to the US in 2002.

During his trip this time, Prime Minister Deuba is expected to meet US President Joe Biden and Secretary of State Antony Blinken, among other high-level officials.

Government officials were more vocal about Deuba’s US visit before the SPP controversy. But now there is a suspicion that the SPP issue may have slowed preparations. Relations between the Deuba and Biden administrations have apparently soured after Nepal’s decision to opt out of the SPP. It is said some leaders in the ruling coalition are urging Deuba not to go.

But foreign policy experts say the visit should take place, and soon, as it gives Nepal an opportunity to clear the misunderstanding over the SPP.

Dinesh Bhattarai, a foreign affairs advisor to two Nepali prime ministers, says the visit is an opportunity to brief the American side about Nepal’s position on the SPP, which helps build better understanding between the two sides.

“Prime Minister Deuba should consult political parties and experts on the issues he will take up with the American side during his visit,” he suggests.

Head of government-level visits are rare between Nepal and the US. Nepal’s prime ministers or heads of the delegation to the UN General Assembly get to meet the US presidents every year for a photo-op. But these encounters are brief and informal.

At an official level, Deuba had last visited the US from May 6-11, 2002. During that trip, he had met President George W Bush to discuss bilateral relations and the Maoist insurgency in Nepal.

No other Nepali prime minister has since been invited to the US. Before that, it was King Birendra Shah who had paid an official visit to the US in 1983.

Even foreign minister-level visits are rare. Former foreign minister Pradeep Kumar Gyawali was invited for an official visit to the US at the end of 2018 after a decades-long gap.

Foreign relations experts say Deuba should take advantage of this rare opportunity. Deuba too understands the significance of his visit. He has already informed coalition partners about it and assured them he will not be signing any military pact with the Americans.

Deuba’s visit comes at a time when Beijing is increasingly opposed to American projects in Nepal. China openly opposed the MCC Nepal Compact and then lauded the Nepal government’s decision to pull out of the SPP. Similarly, through its diplomatic channels, China has expressed concerns over America’s growing engagement with Tibetan refugees in Nepal.

Nepal is getting increasingly tangled in the geopolitical rivalry between China and the US. Bhattarai says Deuba has a chance to firmly state Nepal’s position with the US leadership.

“We should convey a clear message that the US-China rivalry should not spill over into Nepal. We don’t wish to be involved in it,” he says. “The prime minister should not hesitate to make Nepal’s position clear on sensitive issues related to our neighbors.”

China already views the Deuba government as ‘pro-Western’. In February this year, Deuba was even ready to break the ruling five-party alliance to endorse the MCC compact, much to Beijing’s chagrin. And most recently, Nepal seems to have slighted the US by rejecting the SPP.

Soon after the SPP controversy erupted, Nepal Army chief Gen Prabhu Ram Sharma visited the US from 26 June to July 2 and held bilateral talks with Pentagon officials. However, there were no substantial agreements between the two sides. Ahead of his US visit, Gen Sharma had told a parliamentary committee that Nepal Army had decided not to enter the SPP as it was mentioned in the American Indo-Pacific Strategy (IPS) in 2019.

America has a stated policy of enhancing its ties with the countries in the Indo-Pacific region via the IPS. Unlike the previous Donald Trump administration which focused on building ties only with big countries, Biden wants smaller countries in the region on board as well. But the SPP courted controversy in Nepal for its alleged military component in the form of a defense partnership.

Along with regional, geopolitical and other issues, say experts, high-level visits to the US can also boost development collaboration.

Keshar Bahadur Bhandari, a strategic affairs analyst, says the prime minister should ask the US to increase its assistance coming to Nepal via the United States Agency for International Development (USAID).

“Deuba should talk with the US side about enhancing military cooperation in the areas of capacity building and increasing resources to fight natural disasters and other crises. He should also raise the issue of increasing top-level appointments of Nepal Army personnel in UN peacekeeping missions,” Bhandari says.

As the US has expressed an interest in collaborating with Nepal on climate change, such high-level visits could also help boost international partnership to combat climate change in Nepal.

In trade and commerce, the US is one of Nepal’s more important partners. After the end of the quota system under the Multi-Fiber Agreement in 2004, export of Nepali readymade garments to the US declined significantly. Nepal has been advocating for duty-free access of its exports in American markets, especially of readymade garments. Experts say this too should figure in Deuba’s bilateral deliberations in Washington DC.

Ganesh Datta Bhatta: Political leadership has been undermining transitional justice

Nepal formed the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), a transitional justice body to investigate war-era crimes and human rights abuses, in 2014. But there has since been little progress in transitional justice. Political leaders’ lack of the willingness to investigate war-time cases is one reason the commission has failed to work properly. Kamal Dev Bhattarai speaks with Ganesh Datta Bhatta, the commission chairperson.

Can you update us on the commission’s progress thus far?

There is a perception that the commission hasn’t been able to deal with war-time cases. This isn’t true. Despite legal hurdles and resource-crunch, we have made good progress in investigating cases. So far, we have gotten around 64,000 complaints from conflict victims, and we have completed preliminary investigations in around 4,000 cases. Similarly, we have kept 3,000 cases on hold for lack of evidence. Putting cases on hold is not our priority, but our laws don’t permit us to go ahead without solid evidence to establish crime. Doing so is not easy. For that, there should be consensus among five commission members, and the complainants must be informed as well. If needed, we also have to listen to their views on our decision. We have also started detailed investigation of individual cases. In total, we have to probe nine types of cases. Likewise, we have provided identity cards to 600 war victims; a court order has since halted the process. We have also recommended compensation for them.

What hurdles are keeping the commission from working effectively?

The first is lack of human resources to investigate cases. We have received 64,000 complaints and investigating each case is a long and time-consuming process that calls for skilled human resources as well as robust infrastructure. But we have hardly a dozen staff. Frequent transfer of commission employees is another problem. I am sorry to say there is no government support for us. The Covid-19 pandemic also affected our works for nearly two years. To expedite things, we have to set up offices in all seven provinces, and their numbers have to be increased in line with the volume of complaints. But the government and political parties are not being accountable to conflict victims. They fear if the commission is empowered, they could be summoned on war-era crimes and rights violations.

Are there other issues hampering progress as well?

Initially, we formulated ambitious laws and regulations, and took a process-loaded approach. It takes a long time to conclude a single case so we cannot produce an instant result. Similarly, successive governments failed to exercise the desired sensitivity while making appointments to the commission. People who have sound knowledge of laws and Nepal’s peace process should have been appointed, which didn’t happen. The misguided appointment process seriously hampered the commission’s work. Only capable people should be appointed in the commission.

What about the Supreme Court’s order to amend the transitional justice act?

The Supreme Court, international community and conflict victims are all demanding that the Enforced Disappearances Inquiry, Truth and Reconciliation Commission Act 2014 be amended at the earliest. But the political leadership has shown no interest in this. Without amending the laws, the commission cannot work effectively. There are also other issues that need to be addressed urgently. As the investigation process takes a long time, there should be an interim relief package for conflict victims. This gives the message that the state is positive about addressing their concerns. Similarly, the compensation sum of Rs 300,000 must be raised.

How closely is the commission working with the Ministry of Law and Justice?

It is unfortunate that seldom has the ministry cooperated with us. Whenever a new law minister is appointed, he or she doesn’t consult us. They get their information and feedback from bureaucrats. Incumbent Law Minister Govinda Bandi is trying to take a radical approach to transitional justice. The law minister and political leaders are saying that they want to complete the remaining tasks in six months to one year. Such statements don’t help. So, striking the right balance among the stakeholders is going to be difficult. The law minister is undermining the commission by giving an impression that it is the ministry’s task to take the transitional justice process to its logical end. He is bypassing the commission at every step.

We at the commission still want to give him the benefit of the doubt when he says that he can conclude the transitional justice process within a year. But, realistically, the process will take another three to five years, and that too if the commission is fully empowered and allowed to work without a hitch.

“Take something as simple as being referred to as ‘sir’ in work emails. Our society expects only men to be in positions of power,”

China takes a less muscular approach to left unity in Nepal

As political parties mull over the possibility of parliamentary elections in the second week of November, talks of a left alliance are also gathering momentum. And there is a murmur in the political circles that China, once again, is striving to unite Nepal’s communist forces.

It is no secret that Beijing desires a favorable government in Kathmandu—one led by the left, that is. India, the US and the Western countries, meanwhile, want to curtail China’s influence over Nepal.

A Maoist leader tells ApEx that the bitter experience of dealing with the present Congress-led government may have prompted the Chinese to revive the idea of broad left unity and communist government in Kathmandu.

Chinese policymakers believe Sher Bahadur Deuba’s Nepali Congress-led government has deviated from Nepal’s long-standing policy of balanced ties with neighbors.

Beijing also wants to implement all the agreements signed between China and Nepal, which will be possible only with a communist government in Kathmandu. If the current five-party coalition remains intact, the Congress could lead the government again, an outcome that won’t be to China’s liking.

Foreign policy analyst Rupak Sapkota says key external forces are keenly watching ongoing debates on possible alliances. Some of them, according to him, are in favor of giving continuity to the current coalition.

“China obviously wants communist parties to come together and is encouraging the same. That said, our own political forces will have the decisive role in whether that happens,” he says.

Maoist Chairman Pushpa Kamal Dahal has of late hinted at the possibility of allying with the UML. However, Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba believes that the Maoist leader is playing the ‘left alliance card’ just to roil political waters. The prime minister is not ready to sign a power-sharing agreement with the Maoist party in a hurry, unlike in 2017 when Dahal ditched him to side with the UML.

The acrimonious breakup of the erstwhile Nepal Communist Party (NCP), which was born out of merger between Dahal’s CPN (Maoist Center) and Oli’s UML, is reason enough for Deuba to not give in to the Maoist demand.

Still, there are leaders in both the Maoist party and the UML who continue to push for a left alliance, never mind the lack of trust between Dahal and UML chairman KP Oli. A Maoist leader says Dahal suspects Oli of working behind the scenes to break the current alliance and force the Maoist party to contest elections alone.

“Dahal’s suspicion emanates from the fact that Oli didn’t adhere to the power-sharing agreement before. Dahal is worried that he could be betrayed again,” says the Maoist leader.

He adds that Dahal would this time agree to a left alliance or unity only if there is “a clear deal on government and party leadership”.

Bishnu Rijal, UML Central Committee member, says the time is not ripe for the left bonhomie, with the Maoist party still in a formal alliance with the NC.

“Any talk of a left alliance now increases the Maoists’ bargaining power,” Rijal says. “At the same time, there is a strong opinion in the Maoists that alliance and cooperation among communist forces will be easier and more natural than with the Congress.”

Rijal says there can be meaningful talks on the left alliance only after the Maoist party pulls out of the current coalition.

The Maoists and the UML have not stopped exploring the possibility of an alliance though. In recent months, their leaders have been in constant communication. Just a few days back, senior Maoist leader Narayan Kaji Shrestha met Oli to discuss the possibility of a left alliance. Pradeep Kumar Gyawali and Barsha Man Pun, close confidants of Oli and Dahal, respectively, also held similar talks.

The Maoists are better placed to bargain with both the NC and the UML after the party increased its seat number in the local elections in May. Perhaps for the same reason the UML leaders seem more amenable to the idea of a left alliance these days than they were before the local polls.

Oli himself said recently that anything was possible but that the party should also be ready to contest polls alone. There are also strong voices inside the UML that argue that the party could find itself out of power for the next five years without the left alliance.

In order to strengthen his bargaining power, Dahal too is in consultations with the breakaway factions of the mother Maoist party he leads. He has reached out to the splinter parties led by Netra Bikram Chand and Mohan Baidya, offering the carrot of Maoist reunification.

Dahal’s own rank and file are putting pressure on him on left unification. He is said to have delayed the process of appointing party’s office-bearers with the possible unification with other Maoist outfits in mind.

Amid the intrigue surrounding the left alliance, China seems to be making a gentle push.

Beijing is more circumspect about pushing communist leaders to come together because of the backlash it faced in the past. The close engagement between the CPC and Nepal’s communist party had left an impression that China was interfering in Nepal’s internal affairs. This is also one of the reasons ties between Congress and China soured. This time, China is not in a mood to make enemies in Kathmandu.

On June 24, Liu Jianchao, Minister of the International Liaison Department of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China, held separate video conversations with Dahal and Oli.

According to a readout issued by the Chinese Communist Party (CPC), all bilateral issues including Belt and Road Initiatives were discussed. The Chinese leader said Beijing was willing to work with Nepal to implement the important consensus reached between the leaderships of the two countries, deepen political trust, promote major projects, cooperate in various fields under the framework of the Belt and Road, and push friendship across. He also talked about “enhancing the party-to-party relations”.

Last time, China had failed to convince the Maoists and the UML to stay together. And after the two parties split, it tried to unsuccessfully convince the Congress that it would not deal with Nepal on the basis of ideology.

Beijing does not want to repeat that mistake. This time, it has taken a more cautious approach on the left unity. Most notably, China’s ambassador in Kathmandu has not been seen making the rounds of the houses of top communist leaders, ‘urging’ them to mend fences.

Dilendra Prasad Badu: LDC graduation comes with both opportunities and threats

The World Trade Organization’s 12th Ministerial Conference (June 12-16) recently concluded in Geneva, Switzerland. The WTO is the only global international body that sets the rules of trade between countries. Minister for Industry, Commerce and Supplies Dilendra Prasad Badu had led the Nepali delegation to the conference. Kamal Dev Bhattarai caught up with him.

What major agendas did Nepal raise at the conference?

Nepal is a member of the Least Developed Countries (LDCs) group in the WTO. We have a plan of elevating to a ‘developing country’ status by 2026. The interactions that took place at this conference were substantive. We were able to put forth our position firmly. For smooth and irreversible graduation, I emphasized the need for continuation of all international support measures, particularly duty- and quota-free market access, special and differential treatment, preferential rules of origin, service waiver, aid for trade, and flexibilities in the implementation of multilateral trade rules and commitments. However, the issue of giving LDCs a transitional period even after their graduation remains contentious.

Besides, Nepal also raised the issue of food security, among other urgent ones. Since a let-up in the covid pandemic, in line with other economies, Nepal's economy has also regained some momentum. However, it’s getting hard to reposition the country’s economy to the pre-pandemic level, mainly due to the ongoing conflict between Russia and Ukraine, which has impacted the price of petroleum products. The key challenges for Nepal’s economy continue to be widening trade deficit, depleting foreign currency reserves, and poor industrial development.

What challenges will Nepal face after graduating from the LDC status?

Graduation offers us both opportunities and challenges. It brings challenges due to loss of some exemptions and flexibilities. At this critical juncture, we have urged international forums, especially the WTO, the UN and other multilateral funding agencies to ensure adequate transitional support to facilitate smooth, irreversible and sustainable graduation.

The challenges posed by unforeseen crises have reversed our past development achievements, while weakening our ability to achieve SDGs (sustainable development goals) by 2030. Graduating from the LDC status is our common objective as not a single country in this category wishes to remain there forever. Sooner or later, we all want to graduate.

The LDCs are strongly pushing for a reform of the WTO. What is Nepal’s position on this?

At the WTO’s 12th Ministerial Conference, I strongly pitched for all members to stand in favor of reform to make this organization true to its purposes and objectives. But each member country has a different view on the modality of the reform.

In our view, the process should be member-driven, and the LDCs should not be saddled with additional obligations.

Bilateral engagements are equally important to enhance our exports. Did you hold any bilateral talks at the sidelines of the conference?

Along with multilateral arrangements via the WTO, we have to adjust many issues through bilateral means. I held bilateral talks with trade ministers of some countries. For instance, I met India’s Commerce and Industry Minister Piyush Goyal to discuss a range of bilateral issues. I also held talks with my Bangladeshi counterpart.

India recently banned the export of wheat, which could exacerbate Nepal’s food insecurity. Did you raise the issue with your Indian counterpart?

I held an extensive dialogue on a range of issues with minister Goyal. I told him that India’s decision to ban the export of wheat and sugar is a cause for concern for us. He assured me that its neighboring countries are exempt from India’s policy of restricting export.

He even made a commitment that there would be no food crisis in Nepal. I also raised other trade and commerce-related issues with Minister Goyal, including the challenges faced by Nepali industries, particularly concerning exports. He said that any bilateral problems between India and Nepal could be resolved through consultations. He has asked Nepal to come up with a document clearly outlining its problems with exports.

The missing coherence in Nepal’s IPS and BRI dealings

A June 20 Cabinet meeting scotched the idea of joining the US government’s State Partnership Program (SPP) that had run into controversy after being mentioned in the American Indo-Pacific Strategy (IPS). The government took the decision with a view that Nepal cannot and should not be a part of any military strategy.

As the IPS report of the US Department of Defense released in June 2019 stated, “…within South Asia, the US is working to operationalize our major defense partnership with India, while pursuing emerging partnerships with Sri Lanka, Maldives, Bangladesh, and Nepal.” Smaller countries in South Asia including Nepal interpreted this as their forced inclusion in an American military strategy.

The same report mentions Nepal as a recently added SPP member. Then, on 9 March 2021, speaking before the US Senate Committee on Armed Services, Philip S. David, Navy Commander, US Indo-Pacific Command, mentioned how Nepal had “partnered with the Utah National Guard under the State Partnership Program”.

Politicians, policymakers, and a section of intelligentsia agree that joining such a strategy violates Nepal’s policy of non-alignment, even though the US has consistently maintained that the IPS is not a military alliance.

Anna Richey-Allen, spokesperson at the US Embassy in Kathmandu, tells ApEx: “It is important to remember the IPS is not a military alliance and it’s not an agreement—that’s disinformation.”

The IPS, she adds, is a “non-binding US foreign policy expression of commitment” to connectedness, prosperity, resiliency, and security of the Indo-Pacific region.

Many in Nepal remain unconvinced.

Between 2015 and 2019, Nepal twice wrote to the US expressing its desire to join the SPP military exchange program and in this period, there have been some policy changes in the US as well. In February 2022, Joe Biden’s administration came up with a new Indo-Pacific Strategy with three key pillars: governance, economics, and security.

It is the ‘third pillar’ that has raised many eyebrows, even though American officials say the new IPS doesn’t specifically mention the SPP, or for that matter the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC)—another US program that created a lot of controversy in Nepal.

In a recent parliamentary committee meeting, Nepal Army chief General Prabhu Ram Sharma categorically stated that the army had backtracked from joining the SPP after it was mentioned in the IPS.

US officials insist the SPP is not a security alliance. “The State Partnership Program is not and has not ever been a security or military alliance. The United States is not seeking a military alliance with Nepal,” says Allen, the US embassy spokesperson.

“The SPP has existed for over 25 years and includes over 80 partnerships with over 90 countries, the majority of which are not in the Indo-Pacific. SPP’s mention in IPS reports was public and did not change the program,” she adds.

She further explains that the SPP is mentioned in prior Indo-Pacific Strategy reports, but it is not a program arising from the IPS, nor is it integral or bound to it.

Earlier, there was a three-year-long debate on whether the $500 million grant under the MCC Nepal Compact was part of the IPS. A sizable chunk of politicians and foreign-policy experts had then claimed that the MCC was indeed part of the IPS.

That is why Nepal’s parliament endorsed the compact, but with a caveat— a declarative provision stating Nepal shall not be a part of any American military or security alliance including the Indo-Pacific Strategy.

While experts are clear that Nepal should not join a military alliance or strategy, they also say the government should be prepared on how to deal with the IPS.

Sanjay Upadhya, a US-based foreign policy expert, says while not exclusively a military strategy, the IPS contains a heavy security component to advance American foreign policy objectives.

The IPS’s economic and governance components also focus on ensuring a “free and open” Indo-Pacific. American officials have not shied away from proclaiming that the IPS is aimed at confronting China, he says.

“It is unfair of the Americans to incorporate development issues into an explicit geostrategic framework without the consent of recipient countries. Still, it also represents the failure of Nepal’s political, diplomatic and security leaderships to proactively work out the changing dynamics and its impact on Nepal,” Upadhya adds.

Shambhu Ram Simkhada, former diplomat and professor at Tribhuvan University, says there was gross negligence on Nepal’s part both at the time of writing to the US and while withdrawing from the program.

“There was no consultation when the Nepal Army first dispatched a letter of interest in the program, and now the program has been canceled without providing any substantive reason. This exposes our policy inconsistency and erodes our international credibility,” he says.

The US has been coming up with sectoral strategies such as defense and climate change programs to gain regional influence. In May this year, the Biden administration launched the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) with the hope of giving some coherence to the economic pillar of the IPS. The framework was brought with a view that the economy is a critical part of any strategy, including the IPS, in the region. In the coming days, the US is likely to ask Nepal to join the framework as well.

USAID, America’s premier international development agency, is also promoting the IPS in the region. So, in a way, the economic support we get from USAID also falls inside the broader IPS framework.

But then the US is not the actor to retrospectively change the nature of bilateral agreements. Its regional rival China too has put all its assistance under its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) framework.

Initially, the BRI was perceived as a project to disburse China’s loans to build infrastructure projects abroad. Under the initiative, dozens of projects were discussed but now all the bilateral issues have been put under the BRI framework. We cannot rule out the possibility of China tomorrow incorporating security issues in the BRI framework.

Geopolitical analyst Binoj Basnayat says now every other assistance that the US provides is linked with the IPS. But he maintains that there is no harm in accepting bilateral offers.

“We should understand the basic difference between allies and partners. We are not a US ally, for which a formal agreement must be signed. We are like a partner and this doesn’t go against our non-alignment policy,” he says.

He suggests building a mechanism on how to take US assistance. “Let’s work out a mechanism and propose it to the Americans. It is not in the interests of Nepal to keep the US at a distance,” he says.

Mrigendra Bahadur Karki, executive director at the Center for Nepal and Asian Studies, says political parties should forge consensus on how to deal with conflicting strategies of the US and China.

Other experts also suggest that instead of taking a piecemeal approach, the government and political parties should come up with a broader policy on both the IPS and the BRI. As Nepal cannot decide what big powers can or cannot incorporate in their strategies, it should come up with a plan to customize those strategies to fit the country’s needs.

Upadhya says it would be prudent to parse the advantages and disadvantages of individual projects and act accordingly.

“It is easy to say political leadership should stop pursuing narrow partisan goals while asking for development assistance. The diplomatic and security leadership and other influential components of society must rather foster public debate on the wisdom of accepting or rejecting specific projects,” he says.

He is of the view that such public pressure in Nepal would also compel potential donors to abandon their ‘take it or leave it’ attitude.