Pothi Incubator: Hatching success

Suman Paudel, a former researcher at Nepal Academy of Science and Technology, began working on the idea of egg-incubation after learning that Nepal’s poultry industry was sending out around Rs 400 million a year to import these egg-incubating (hatching) machines.

He assembled a small team of mechanical and electrical engineers to give shape to his project and developed three prototypes at a modest cost of Rs 200,000. And so began the story of Pothi Incubator in Tikapur, Kailali.

“Our first machines had a 65 percent success rate, which was a decent result,” says Paudel, the CEO of Pothi Incubator. “We then tweaked and made further changes to the machines for market production.”

Paudel says when the first incubators were introduced, many poultry farmers looked askance as they were not used to seeing Nepal-made machines. It took some time for the farmers to accept these domestically made egg-hatching machines.

“We have sold nearly 100 machines so far,” says Paudel.

Pothi Incubator hit its stride after moving to Butwal. Given that most poultry farms are based in eastern part of the country, Paudel says the company had to relocate.

“Operating from Tikapur, it was difficult to transport egg incubators because of our poor highways,” he says.

Besides building its own hatching machines, Pothi Incubator also offers technical assistance to poultry farmers, like repairing and increasing the efficiency of their machines built by third parties.

The startup has helped the owner of an ostrich farm in Bhairahawa modify his US-built egg incubator so that it can hatch up to 1,800 eggs at once. Besides, it also conducts real-time monitoring of machines used by the clients using digital technology.

“We can monitor the machines remotely using a mobile app to see if the machines are functioning optimally,” Paudel says. “We developed this system as our clients are based far away from our office.”

The company’s contribution to the country’s poultry sector has not gone unnoticed. Its egg-hatching machine was awarded first prize under the ‘Made in Nepal’ category by Idea Studio, a platform for sharing business ideas.

Pothi Incubator is currently producing four ranges of egg hatching machines. Paudel says a fully automated egg incubator is also in development with the support of the National Innovation Center.

“We now want the government to improve our market access,” Paudel says.

Pothi Incubator

Establish year: 2020

Founder: Suman Paudel

Service location: All over Nepal

Price of the product: 176 eggs: Rs 40,000; 500 eggs: Rs 70,000; 700 eggs: Rs 80,000; 1056 eggs: 105,000 (normal), 120,000 (advanced)

Contact: 9848558143

Social media link here.

Oho! Cake: Here to change cake culture

Santosh Pandey was already running a successful ‘gifting’ startup when he came up with the idea for ‘Oho! Cake’.

At ‘Offering Happiness’, his first company helping people send gifts and organize surprise parties for their loved ones, he had realized the potential of the cake business.

Pandey says cakes have become staples for any celebration these days but there aren’t many cake companies in Kathmandu that are consistent with their product quality and service.

“We started off with the idea of building a reputed cake business as that was what the market and the customers were missing,” he says.

Pandey and his friend Dibyesh Giri, who comes from a tech background and is currently based in the US, set up Oho! Cake in 2021. The time was not auspicious for a new business. Many businesses were either folding up or struggling to stay afloat due to covid. But food delivery was booming. Oho! Cake thus had no trouble finding customers even during the lockdown.

Before venturing into cakes, Pandey and Giri had already done their homework. The two friends studied customer needs and identified the areas they could improve upon from what their potential competitors were offering.

Pandey says cakes worth over Rs 5 million are sold daily in Kathmandu Valley. Most people buy ready-made cakes from their local shops or order them through delivery platforms that mostly drop-ship goods purchased from third party retailers. Moreover, he adds, there are many complaints of late delivery.

“At Oho! Cake we guarantee delivery of freshly baked cakes to our customers within 45 minutes of order,” Pandey says. “Our motto is simple: If you value the customers’ time, your business will succeed.”

Oho! Cake runs its operations with imported machines and technology that have the capacity of preparing more than 500 cakes with customized designs in a day. It currently handles over 100 daily cake orders.

For now the company offers its service only inside Kathmandu Valley, but its co-founders are already planning to expand.

“In the initial days Oho! Cake was limited to online platform delivery, but we have recently opened our first outlet at Tinkune,” Pandey says.

The company is planning to open at least 10 more outlets in different parts of Kathmandu Valley in the first half of 2022 before branching out to other parts of the country.

“Our ultimate goal is to become the country’s largest cake chain,” says Pandey.

Entering the cake business has been a fulfilling experience for him. He takes pride and comfort knowing that Oho! Cake is part of joy and celebration for its customers.

“We get many thank you messages from our customers. Their good words give us great satisfaction and inspire us to do ever better,” says Pandey.

Oho! Cakes

Establish year: 2021

Founders: Santosh Pandey, Dibyesh Giri

Service location: Kathmandu Valley

Price of product: Varies depending on weight and design

Contact: 9886049922

Website: ohocake.com

Radheshyam Adhikari: Far too early to discard the National Assembly

The Election Commission recently elected 19 National Assembly members. In this connection, Pratik Ghimire of ApEx talked to Radheshyam Adhikari, outgoing National Assembly member of Nepali Congress, on the assembly’s shortcomings and achievements over the past four years.

What are the major duties of the National Assembly?

Besides formulating and passing bills, the National Assembly oversees and instructs the works of the government. It also discusses and sends resolution proposals on national issues, projects of national pride, and issues of public interest. Besides, the assembly examines the delegated powers of universities and other delegated legislative bodies.

How do you evaluate the past four years of the National Assembly?

The assembly could certainly have performed better. As we have diverse duties, there may have been some shortcomings. But that doesn’t mean we didn’t perform at all. We updated and offered suggestions on many important bills to the lower house. For example, the draft of the Passport Bill sent by the lower house was so regressive that all the power was centered on the government. It was the upper house that made sure that the bill would be universal and accessible to all and updated it accordingly. We also revised the bill to amend the Citizenship Act and the Nepal Special Service Bill on counterintelligence, among others. The controversy surrounding the Guthi Bill was also resolved after the assembly revised its draft.

So why is the assembly repeatedly accused of underperformance?

There are fewer sessions of the National Assembly, say compared to the House of Representatives sessions. Our sessions are only called when the lower house is active and it has kept us in the shadows. The conflict among the political parties in the lower house has hamstrung the performance of the upper house as well.

Do we really need the National Assembly? Isn’t the House of Representatives enough?

It is too soon to debate that. Everything has its time and the National Assembly must be given enough time to perform. If the assembly could not perform as expected, say after the next two elections of the lower house, then this debate could be relevant. For now, we should debate how to bring deserving members to the assembly and work effectively.

We also need the National Assembly to honor the spirit of check and balance. As I mentioned earlier, the upper house has done a lot of work on important bills. The lower house has a tendency of working in a rush. It always forwards bills that are incomplete and full of ambiguities. It is the work of the upper house to address those issues.

Has the National Assembly become a platform for parties to accommodate leaders who fail to get into the lower house?

I don’t think that is the case. There are many deserving leaders who have made decent contributions to bring political changes in Nepal since the 1990s, and they have not gotten the chance to serve the nation. So bringing them into the National Assembly is only fair. But I do believe that the assembly is a chamber of intellectuals and experts, and that its members must have required skills and qualifications.

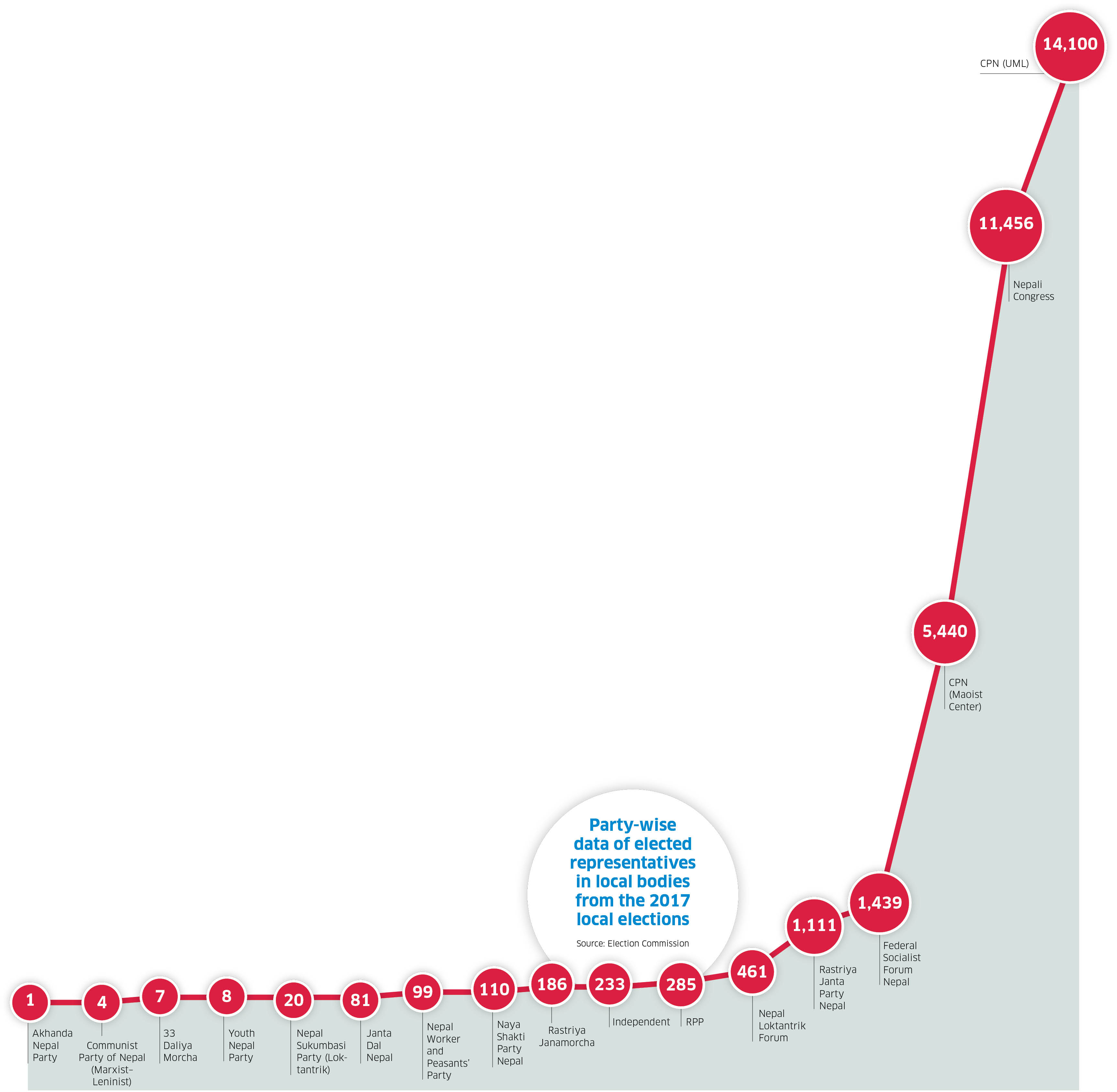

Representation at the local level

As per the suggestion of the ruling coalition, the government and the Election Commission have tentatively agreed to hold local elections in one phase on May 18.

The major political parties have already started preparing. But there could be plenty of political drama before the election-day. Speculations are already rife about election outcomes and positions of major parties.

In the past five years, there has been a lot of turbulence inside major parties. In 2018, the CPN-UML and the CPN (Maoist Center) united to form the Nepal Communist Party (NCP), but the Supreme Court in March 2021 voided the merger and revived the old parties. Madhav Kumar Nepal then went on to split the UML to form CPN (Unified Socialist), becoming the fourth largest parliamentary party.

Maoist chairman Pushpa Kamal Dahal ‘Prachanda’ and CPN (Unified Socialist) leader Nepal have made it clear that they want a continuity of the ruling coalition under Nepali Congress until the elections. However, there is a strong voice within Congress that it should not ally with any of the leftist parties. The UML, meanwhile, wants to break the coalition and isolate Congress in order to retain the position of the largest party.

“As the parties have no new political agenda, the only way to win more seats is by cutting the votes of rival parties. So the smaller parties could play a vital role by splitting votes,” says Bishnu Dahal, a political analyst.

Similarly, in 2019, Baburam Bhattarai-led Naya Shakti Party and Upendra Yadav’s Federal Socialist Forum merged to form the Samajbadi Party Nepal. Then in April 2020, the party merged with the Mahanta Thakur and Rajendra Mahato-led Rastriya Janta Party Nepal to form Janta Samajbadi Party Nepal. But after little over a year of working together, the Thakur-Mahato faction broke off to form the Loktantrik Samajbadi Party Nepal. The effect of mergers and breakups in political parties is certain to reflect in poll results as well.

Bibeksheel Sajha Party remains without representation at the local level, and it plans to change that this time around. Bibeksheel Chairman Rabindra Mishra recently changed the party’s line and is now pitching for return of monarchy and referendum on Hindu state. There are rumors of Bibeksheel forming an electoral alliance with the pro-monarchy Rastriya Prajatantra Party (RPP) for local polls.

The two parties have already discussed the possibility, and the RPP’s newly elected chairman, Rajendra Lingden too seems keen on working together with like-minded forces, at least for the elections.

“This time, the parties will focus on defeating others rather than winning elections on their own strength,” Dahal says. “There is a likelihood of UML and Congress contesting alone while the remaining parties could form an electoral coalition against the Big Two, making it a three-way fight.”

Tenzing Sherpa: Nepal’s pioneering DJ

When Tenzing Sherpa got the role of the ‘music player’ in Club Jolly Blues—the first discotheque in Kathmandu—back in 1992, he didn’t know the profession was called disk jockeying. He was an ordinary music-loving teen who used to go to the club every evening to listen to music and the club owner, with whom he had developed a friendship, offered him a job. He got himself the stage name DJ Tenzing and started playing with CDs and simple mixing devices as there were no professional instruments or training in Nepal in those days.

Born and raised in Solukhumbu, Sherpa came to Kathmandu for higher studies after completing his SLC. Until then, he had no fixed aim in life. He just wanted to make enough to pay his college fees and rent. “I used to leave the club at 2 am and attend my college at 5 am,” Sherpa shares about his initial days in the profession. “I then slept after returning from college at 9 am.”

Even long after starting out on this journey, he hadn’t dreamt of a professional career as a DJ: playing music was just a hobby and a small source of pocket money. But DJs started getting space on outdoor musical concerts and festivals after 2006, which made them more sought-after and increased their earnings too, and it was only then that Sherpa chose DJ as his permanent career. By then, the Internet and other technologies had also developed, which came in handy for him to practice new styles of playing.

After seven years at Club Jolly Blues, in 1999, Sherpa joined Club X-zone at Durbar Marg. He played there for around three years. He also worked at Hyatt Regency’s Rox Bar and Hotel Yak and Yeti’s Club Platinum. He started doing freelance shows from 2008. Till date, he has done over 1,000 stage programs in and outside the country, including in the US, the UK, Korea, Japan, Israel, Germany, Belgium, France, Luxemburg, Portugal, Spain, Netherland, Hong Kong, Qatar, and India, among other countries . “There is nothing better than seeing people dance and love your remix,” he shares when asked about the best part of being a DJ.

Also read: Sugam Pokharel: The ideal Nepali pop culture Idol

In 2007, to promote his maiden album “DJ Tenzing”, he organized “DJ Tenzing All Nepal Tour” with several popular Nepali singers. The album includes various popular songs like ‘Isarale Bolaunu Pardaina’, ‘Jham Jham Istakot’, ‘Jhimkai Deu Pareli’, ‘Lalupate Fulyo Banaima’, ‘Yo Gaun Ko Thito Ma’, etc. Sherpa has also done a show at Everest Base Camp with the theme of “Stop Global Warming and Save the Himalayan”. Besides that, he was one of the judges in a DJ reality show “War of DJ” which aired for three seasons from 2010 to 2012.

“I have seen many ups and downs in the DJ fraternity during my three decades in the industry,” he says. For example, in the past, DJs didn’t have money, but they had prestige, but these days, things are exactly the opposite, Sherpa remarks. DJs are only regarded as ordinary guys with laptops and headphones, he notes. “I have groomed myself by mixing manually but youngsters nowadays just put software at auto-tune,” says Sherpa.

“I wish the government had plans to promote nightclubs as they also attract a decent number of tourists and thus contribute to the economy,” he says. Sherpa thinks that these clubs, which employ people from diverse backgrounds, have been devastated by the pandemic. But instead of helping them out in these difficult times, the government seems intent on stifling their growth, he laments.

There are many DJs in town today: half in the scene to cultivate their hobby while the other half is determined to make it a career. Sherpa sees the future of DJ aspirants as bright as the number of clubs in the country is steadily rising. “It is not that difficult to sustain financially, and if you can maintain good PR, you will get the shows and tours on a regular basis.”

Vijay Kumar Sarawagi: Birgunj is ready for the new covid wave

Open borders with India represent a major challenge in stemming the spread of coronavirus. With cases in India peaking, entry points on Nepal-India border have been put on high alert. Birgunj, the busiest Nepal-India gateway, is often regarded as Nepal’s Covid-19 hotspot. This time too, the city has seen cases steadily rise. Pratik Ghimire of ApEx talked to Vijay Kumar Sarawagi, mayor of Birgunj Metropolitan City, to know about their preparations and plans to contain the spread.

How are your preparations for the third wave?

Having fought valiantly against the two previous waves, Birgunj is ready to deal with the new wave with the help of our added manpower and resources. We have focused on Narayani Hospital where we have installed an automatic oxygen plant with the capacity to fill over 200 oxygen cylinders a day and oxygen lines have been added to over 600 beds, to be fed directly from the plant. As unvaccinated children are vulnerable, we have established a special child ward with all instant facilities.

Besides, we have added health desks at borders and increased the number of community contact tracing teams. Vaccination has also picked up in our metro.

What is the state of your isolation centers?

Our isolation centers have not been used as almost every covid infected individual is isolating in their homes. Moreover, it looks like this wave is less harmful as even those who are admitted to hospitals are being discharged within a week. We have also not allowed a single person to enter Nepal without a negative antigen test. Yet, for an emergency, we have built a 400-bed holding center, which can also be used for isolation.

Also read: Dinesh Kumar Thapaliya: Commission ready to hold local elections on April 27

There seems to be a lack of public awareness in the metropolitan city. How can you convince citizens to follow health protocols?

We admit that the virus has already spread in the community because almost 70 percent of those being tested are returning positive results. Many with mild symptoms are not even getting tested. They are rather self-isolating in their homes. We are encouraging them to test through various digital campaigns and are also planning to provide door-to-door PCR services. The District Administrative Office (DAO) has been monitoring compliance of protocols, and imposing a fine of Rs 100 on those violating the rules. We also provide masks to those who appear without them in public places.

Birgunj has vaccinated 57 percent of its eligible population, and many have even received doses from India. So, tentatively, over 80 percent of our citizens are vaccinated. As it is common to have a cold during the winter, people might ignore mild symptoms. Our metro has almost 30,000 children above 12 who are eligible for vaccines, and 20,000 of them have already been vaccinated. We are waiting for vaccines for minors under 12.

How much has the metro spent on covid crisis management?

We have allocated Rs 30 million for it but the fund has barely been spent as provincial and central governments have taken care of most expenses.

How has the coordination been with other governments and departments?

There is no problem between us and the DAO. But coordination among municipalities is lacking. For instance, as Birgunj is more developed compared to surrounding areas, people from neighboring municipalities come to Narayani Hospital, which is causing an overload. We have to manage logistics for that. With more support from provincial and federal governments as well as municipalities, we will surely be in a position to provide better services.

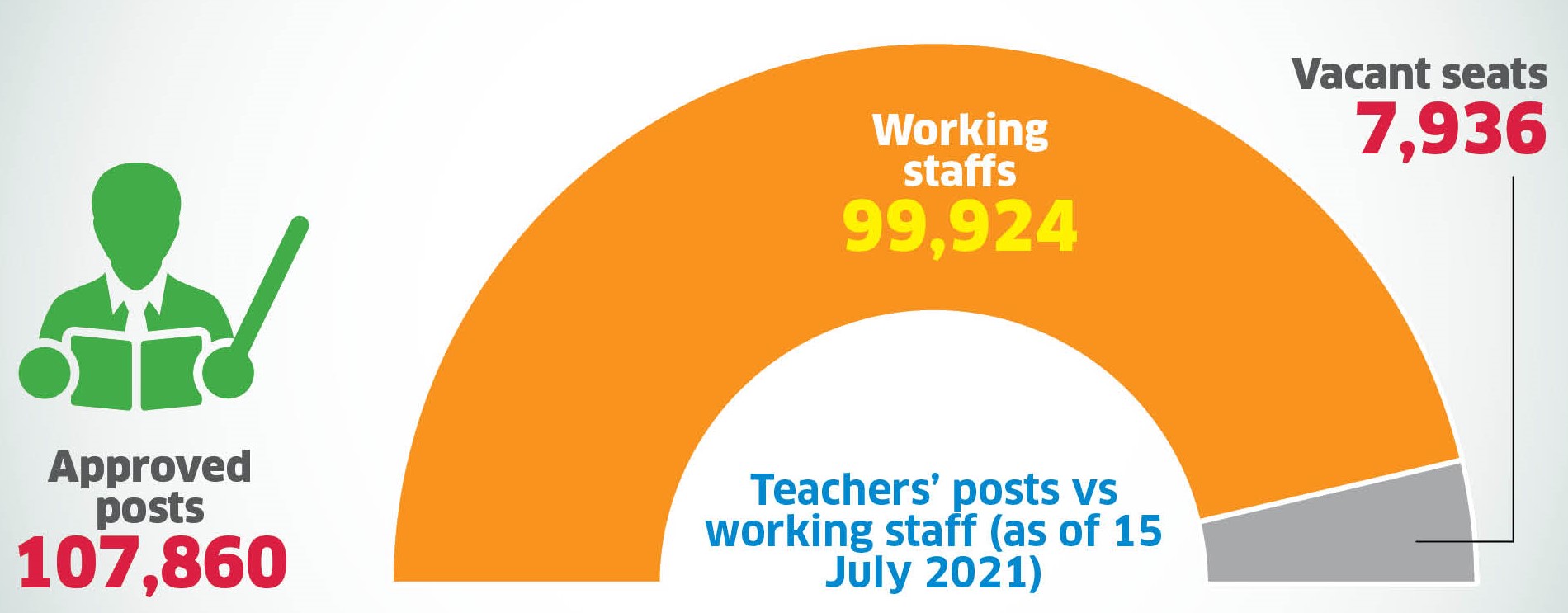

Local level facing an acute shortage of civil servants

With the promulgation of the new constitution in 2015, Nepal adopted a federal system with three tiers of government—federal, provincial and local—thereby restructuring the unitary state into a federation. This increased the number of government offices, leading to a surge in demand for workers. For instance, the offices and ministries of the seven federal provinces automatically increased the need for additional staff. In the new federal set-up, there are six metropolitan cities, 11 sub-metropolitan cities, 276 municipalities, 460 rural municipalities, and 6,743 wards. Civil servants are required to run these offices, besides supporting the functioning of elected representatives. Moreover, various departments have added branches so that citizens can conveniently get services.

As expected, there has been a severe staff shortage. Before the 2017 local level elections, the Ministry of Federal Affairs and General Administration, in coordination with the Public Service Commission (PSC) and other concerned authorities, had initiated homework to meet the workforce demand. Five years on, progress has been patchy. The tenure of elected local governments is ending in May 2022.

Immediately after the formation of local governments, elected representatives started complaining about the lack of civil servants. Of the almost 65,000 posts approved for the local level, more than half (i.e. 34,473) seats are still vacant. The recruitment process was moving ahead smoothly, but the ministry’s attempt for adjustment of civil employees resulted in shortage of staff in almost every local level office, hindering service delivery.

A related problem is lack of laws mandating coordination and cooperation between the federal and provincial governments. The federal government is still reluctant to delegate power to the provinces, preventing them from recruiting the required staff on their own.

Also read: Nepali political parties far from inclusive

Even though there could be no smooth adjustment of civil servants, the Nepal Police claims to have more or less adjusted its personnel in the federal and provincial governments. Right now there are 4,000 vacancies in Nepal Police but that is normal, says SSP Bishnu Kumar KC, Spokesperson and Information Officer of Nepal Police. At the end of each year, they prepare a list of approved posts and incumbent staff and coordinate with the Ministry of Home Affairs and Public Service Commission on new recruitment. Throughout the year the number of staff decreases due to resignation, retirement, and deaths. “We have deputed extra personnel in Province no. 1 and Sudurpaschim, and slightly reduced personnel in other provinces,” he adds.

Almost 8,000 seats of teachers are vacant, currently filled with temporary teachers appointed on contract basis. Temporary hiring has given rise to nepotism, favoritism and corruption, as school heads have the authority to utilize and manage school’s resources and manpower.

We need more technical civil servants

Kashiraj Dahal

Local bodies are our major service providers as they are directly associated with the public and with broad work areas. They thus need more civil servants. But 55 percent of the allocated seats in local level civil services are vacant, creating a void between government and the public. The concerned authorities should immediately fill these vacant seats via federal and provincial Public Service Commissions. Prior to that, the parliament should pass the ‘Nijamati Ain’, which upholds the essence and importance of civil services.

The government must focus on recruiting professional technical staff, as their multiple skills will help get governmental work done in less time. It will also restore the credibility of the civil servants who are often accused of not doing their jobs on time. I believe in quality not quantity, so let’s not count posts but adjust them on a need basis. Our administrators have no idea of work division, but without it, we can’t be competent as well.

Dahal is an expert in public administration and former Secretary of the Nepal government

ApEx roundtable on problems of people with disabilities

Every disability is different. But all its variants hinder functionality, in one or the other way. While some disabilities might be visible, others that affect cognitive or learning abilities are called ‘invisible’. Nepal is still a long way from addressing the issues of persons with disability (PWD), mainly due to lack of coordination between different government agencies.

Representation is another issue that needs to be addressed. Although political parties have quotas for people with disabilities, discrimination against them continues: those getting the benefits are mostly the kith and kin of influential politicians. Though PWDs get identity cards, there is no census or a proper system for their documentation. Disability is still socially stigmatized, preventing parents and people in general from freely talking.

ApEx recently organized a roundtable on the topic with the objective of understanding the basics: the most common forms of disabilities in Nepal and the problems the sufferers face. Here are excerpts.

Rama Dhakal, Vice president, National Federation of the Disabled Nepal

Those like me with physical disabilities are at least visible and the media take up our issues to an extent, but those with invisible disabilities seldom get the needed exposure. Yet the biggest issue for all of us continues to be lack of inclusion in policy making. Political parties have ignored the essence of the constitution and misused PWD quotas by nominating their yes-men—those who don’t even consider themselves PWD. If people representing us can’t make it to the decision-making level, no one is going to advocate on our behalf and our issues will continue to be sidelined. Besides our mental, physical, and financial difficulties, lack of concern being shown by our political stakeholders is also a huge problem. This was also reflected in the recently concluded general conventions of major parties, where the issues of the PWD were completely sidelined.

Also read: ApEx roundtable: Mental health, youth and the pandemic

Devi Acharya, Chairman, Nepal Spinal Cord Injury Sports Association

A spinal cord injury (SCI) is a physical and visible injury, resulting in loss of functions such as mobility and feeling. Around 70 percent of SCI cases are the result of accidents at home like falling from trees or cliffs. A series of things should be done to stabilize an SCI victim, to be carried about step by step. That is an issue. There are hardly any professionals to assist disabled people in hospitals or disabled children in schools. Our hospitals lack even basic medical facilities for them. It takes hours or at times even days for a PWD to reach the hospital. Besides, we don’t have proper rehabilitation equipment, and the professional help needed to diagnose and treat SCI patients is inadequate as well.

Lakpa Norbu Sherpa, Chairman, Society of Deaf-blind Parents

Deaf-blindness is a combination of sight and hearing loss that affects a person’s ability to communicate, access information, and move around. Among different forms of disabilities, deaf-blindness is among the more severe one. My son has deaf-blindness and either my wife or me have to be with him all the time. People with this disability have no access to education, transport, and other daily needs. We, caretakers, are ignored by the government, and nor can we go outside our homes for advocacy. So we have been deprived of our shares of allowances and facilities.

I sometimes feel people with minor disabilities have suppressed our issues. Alongside, the concerned stakeholders have not been able to create an environment for an inclusive school where students with any disability can attend. If we could send our children to such schools, perhaps they could feel like other regular kids, which is also important for their sound mental health.

Also read: No political party for Nepalis with disabilities

Dr Sunita Maleku Amatya, Chairperson, Autismcare Nepal Society

My son has autism, which means he has difficulties in social interactions due to his repetitive patterns of thought and behaviors. This is referred to as a developmental disorder of variable severity. It is important to diagnose it early to cope with it the best possible way. In developed countries, the newborn are tested for the functionality of their organs and treated in case a disability is found. Unfortunately, our health service has no such mechanism for screening, delaying diagnosis. Problems are compounded by lack of further treatment and services, even though timely recognition and treatment could minimize the damages. Moreover, caretakers have a huge role in the life of PWD. Mental health of the caretakers should be prioritized and they should be recognized, appreciated and made more visible.

Shila Thapa, President, Down Syndrome Society of Nepal

Down syndrome is a condition in which a child is born with an extra copy of their 21st chromosome, resulting in physical and mental developmental delays and disabilities. But they can still live a healthy and fulfilling life. My son has this condition. What each stakeholder should know is people with Down can be valuable employees and are also ready to work, but often lack training and opportunity. The government has not done anything to help them be more independent. Nor has it financially supported the guardians of children with Down. The current government monthly allowances are peanuts. So the problems with all kinds of disabilities can be alleviated with due attention of policymakers as well as greater social awareness.