Dhruba Kumar obituary: A towering scholar

Birth: 1949, Kathmandu

Death: 16 March 2022, Kathmandu

At a time when most Nepali professors, intellectuals and civil society leaders like to attach themselves to political parties to curry favors, Prof. Dhruba Kumar, who died aged 73 on March 16, was a rare exception.

He was an inspiration for the advocates of democracy and human rights. Prof Kumar was among the few intellectuals in the country with vast knowledge in foreign, defense, geopolitical and strategic affairs. Crucially, he possessed the rare knack of explaining these complex topics to the public with clarity and simplicity.

All his life, Prof. Kumar was an ardent champion of equality and social justice. He was against all kinds of discrimination and never used his surname in his journals, books and columns.

Despite being a profoundly learned man, he never had an air of self-importance.

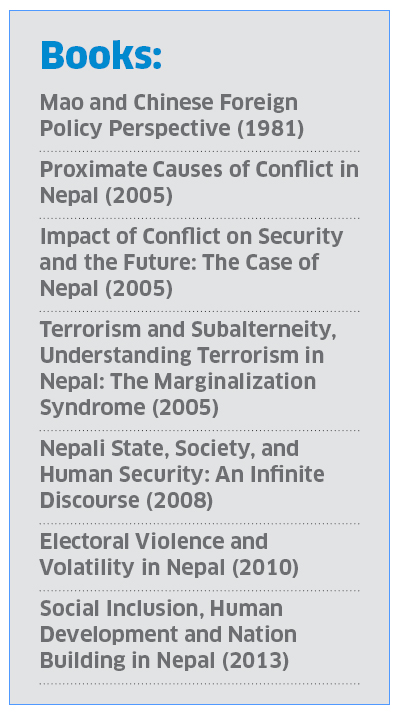

A retired professor of Political Science at the Center for Nepal and Asian Studies (CNAS), Tribhuvan University, he was a passionate researcher on the politics of South Asian countries.

More recently, Prof. Kumar’s columns focused on relations between Nepal, India and China, where he discussed India’s ‘hegemonic tendency’ and China’s ‘silent tactics’.

Prof Kumar began as a China scholar at CNAS and gradually expanded his study and research in other South Asian countries, becoming one of the authorities on the region’s strategy, diplomacy, security and geopolitics.

His fellow professors at CNAS remember Prof. Kumar as an inspiration for all scholars.

“He was the one to start the culture of academic research on security affairs,” says Krishna Khanal, who had worked with Prof. Kumar at CNAS. “He was also a pioneer in the study of Chinese politics.”

In his academic career, Prof. Kumar wrote many books on foreign affairs, conflict and security. He also participated in fellowship professor exchange programs in universities around the world. He was a FCO Fellow at the Department of War Studies in King’s College London, England; Ford Visiting Scholar at the Program in Arms Control, Disarmament and International Security in University of Illinois, Urbana Champaign, Illinois, USA; and Visiting Fellow at the Faculty of Asian and International Studies in Griffith University, Brisbane, Australia.

Prof Kumar worked as a full-time professor at the School of International Development and Cooperation (IDEC) in Hiroshima University, Japan. In 2002, he was a member of the SEAS 2002 Conference that was jointly sponsored by the US Commander-in-Chief Pacific (USCINCPAC) and the Department of State for Security Professionals of the Asia/Pacific Region.

He is survived by his wife and three daughters.

What if… the fast track project was completed on time?

A Kathmandu-Tarai expressway to link the valley with the Tarai plains via the shortest-possible motorway was conceived decades ago.

But the idea didn’t come into fruition due to various technical, political and financial hurdles. Then, in 2017, the then Pushpa Kamal Dahal-led government officially handed over the project to the Nepal Army.

The initial deadline of the expressway was Sept 2021 but was extended to Jan 2025 due to lack of progress: the army has completed just 16.10 percent work till date.

As work on one of the country’s flagship infrastructure projects sputters on, a dwindling number of people believe the fast-track, even if completed someday, will have the desired impact on development.

But how would Nepal have gained had the fast track been completed by its initial 2021 deadline?

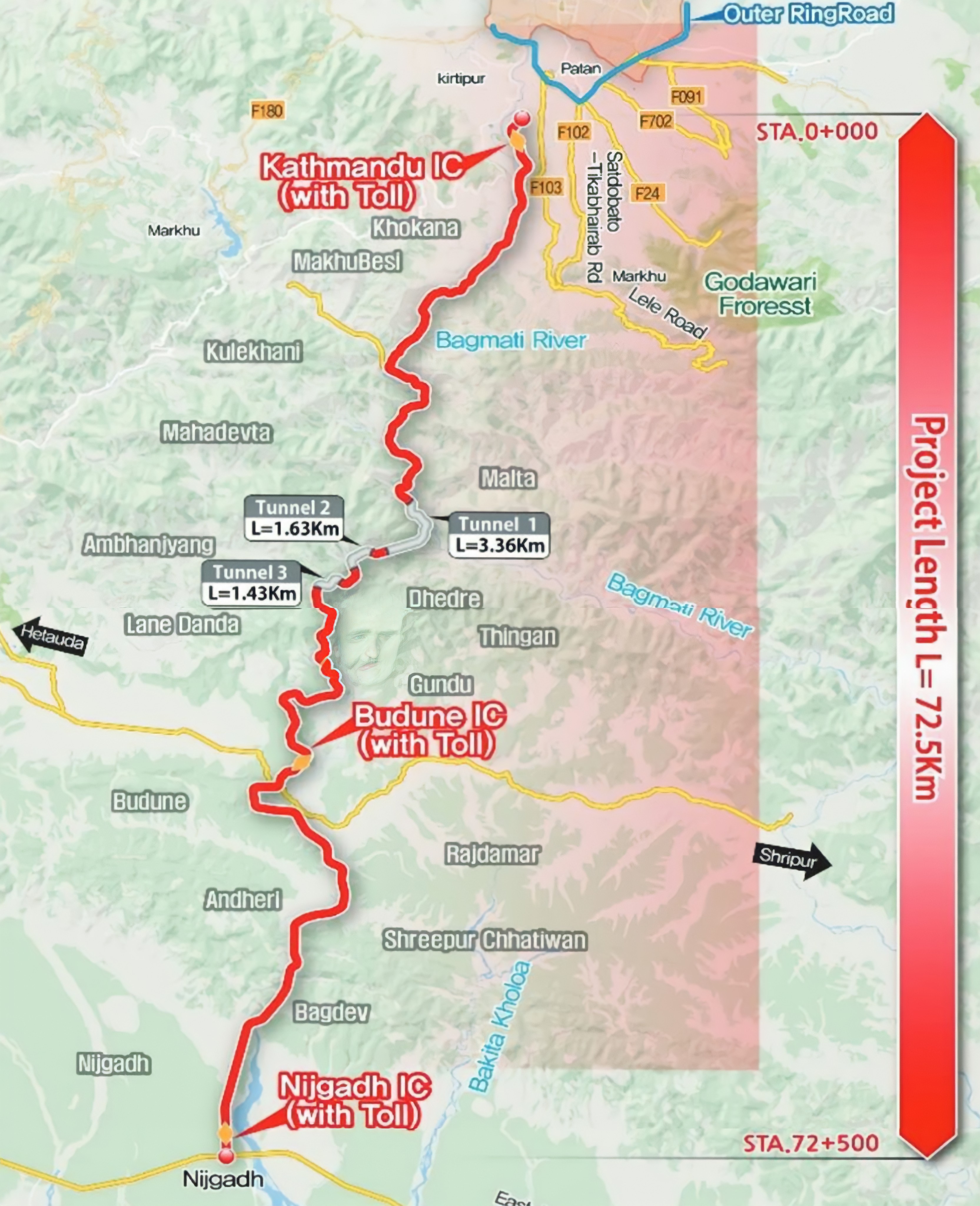

First, says Uma Shankar Prasad, a member of National Planning Commission, the 72.5-km route would have drastically reduced the travel time between Kathmandu and Nijgadh of Bara district in the Tarai.

“This would have saved the country millions of dollars by reducing fuel consumption and vehicle maintenance cost,” he says. “We would have had a better balance of payment and smooth and fast transport would have contributed to our GDP.”

But a former secretary of the Nepal government, who has been closely following the project, does not see the expressway as economically viable.

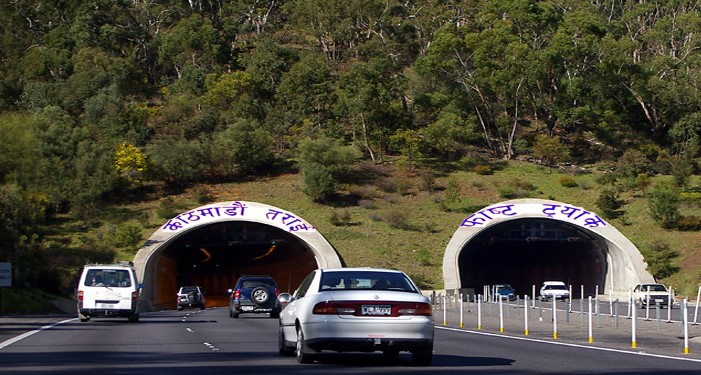

A concept picture of twin tube exit of Kathmandu-Tarai fast track.

A concept picture of twin tube exit of Kathmandu-Tarai fast track.

“There would have been no meaningful change even if the project was completed in 2021,” he says while requesting anonymity. “The fast track cannot generate profit and will thus be a burden for the government. He says the fast track’s passage through an earthquake-prone area presents additional challenges.

In fact, the burden on the treasury has increased.

The government in 2021 completed the construction of dry ports at Birgunj and Chobhar. They were built exclusively for the expressway. Had the fast track been completed earlier, the dry ports could have started generating revenue—rather than bleeding money as they currently are.

Due to inflation, the estimated project cost has risen from Rs 80 billion to Rs 175 billion. Moreover, the NPC now reckons the expressway could cost Rs 213 billion in current prices, reaching a high of Rs 300 billion by Jan 2025.

“Even in a straightforward calculation, timely completion would have saved us almost Rs 80,” says Chandra Mani Adhikari, an economist and former NPC member.

He says a completed expressway would not just have improved Nepal’s trade access, but also increased Nepal’s production and export capacities.

Research suggests Kathmandu-Tarai fast track would decrease national fuel consumption by 20 percent. “Even with the saving of 10 percent fuel, there will be a national saving of Rs 20 billion. This is important, given that Nepal imports almost Rs 200 billion worth of fuel a year,” says Adhikari.

A concept picture of twin tube entry of Kathmandu-Tarai fast track.

A concept picture of twin tube entry of Kathmandu-Tarai fast track.

The former government secretary does not agree.

“Japan and the Asian Development Bank (ADB) have conducted separate feasibility studies on the fast track. They suggest the route could be underutilized as there are many other road links between Kathmandu and Tarai,” he says.

Moreover, the estimated 90-minute travel time is applicable only for passenger buses and cars, not cargo trucks, which could take 5-7 hours to traverse the route.

Impact on other projects

Investing in Nepal’s mega infrastructure projects is widely considered unwise. The country lacks a good precedent. All 21 national pride projects are behind cost and schedule. The Upper Tamakoshi Hydropower Project, for instance, had an initial estimated cost of Rs 25 billion when the project began in 2011. It was supposed to be completed in 2018. When the deadline was pushed to 2021, the cost ballooned to Rs 90 billion. The Melamchi Drinking Water Project is also suffering a similar fate.

“Timely completion of the fast track would have set a wonderful precedent and could also have hastened work on other national pride projects,” says Govinda Raj Pokharel, the former NPC vice-chairman.

He says timely completion would also have helped attract investors to other important projects.

The airport link

The proposed Nijgadh International Airport is another project directly linked to the Kathmandu-Tarai fast track. Experts say the two projects were pitched around the same time, as they complement each other.

Pokharel, the former NPC vice-chairman, says timely completion of the fast track would have added impetus to the airport project.

“It would have put pressure on concerned parties to expedite works on the airport, which, when complete, will naturally boost traffic on the fast track,” he says.

For now, the fast track project drags on with no certainty of whether the army will require further deadline extensions.

Binoj Basnyat, a retired Nepal Army major general, thinks the army made a strategic miscalculation by accepting the fast track project, which has dented its credibility.

“The project’s timely completion would have enhanced public faith in the army. But the reverse is also true: the army’s competence is being questioned over the long delay on the fast track,” he says.

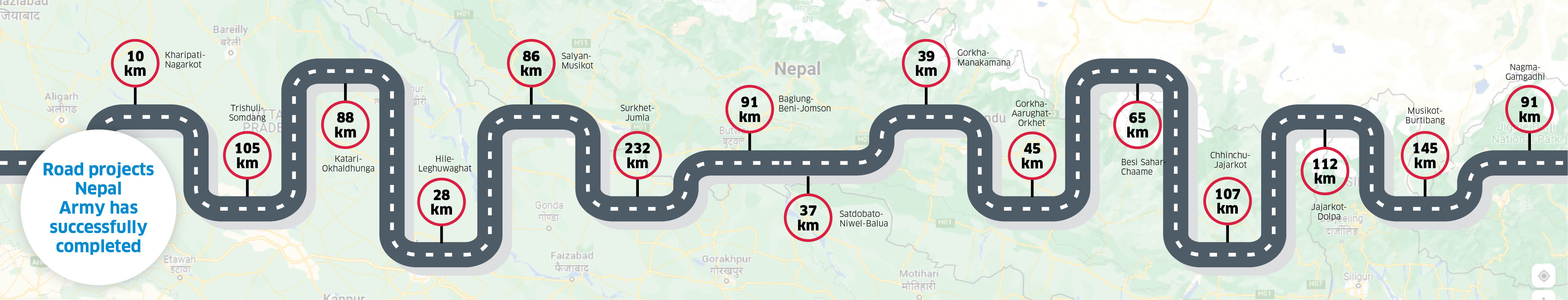

Lack of fast track progress raises questions over Nepal Army’s credibility

An ApEX team was recently on a field-reporting trip of the Kathmandu-Tarai Fast Track Road Project. Our objective was to document progress on the 72.5km expressway that will connect Kathmandu valley with Bara district in the Tarai, considerably cutting time and distance between these economic fulcrums of the country.

At a project site at Bandarekholchha of Makwanpurgadhi Rural Municipality in Makwanpur district, we spotted a villager arguing with a Chinese excavator operator.

Ram Bahadur Waiba, we learned, was angry about indiscriminate felling of trees. The stumps of freshly cut trees were before our eyes, and Waiba, despite the language barrier, was demanding an explanation from the Chinese worker.

“They [Chinese workers] have chopped down almost a dozen trees for which they have no permit,” Waiba told ApEx.

There was an army camp nearby to listen to and address the concerns of the people living in and around the project site. But Waiba said the army had ignored their complaints.

Also read: Photo Feature | Tracking the fast track road project

It was a clear case of the project contractor violating the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) report. The army had already cut down the required number of trees in the area to make way for the fast track. Felling more trees is against the EIA mandate. The residents of Bandarekholchha told ApEx that neither them nor the forest department was informed before the trees were axed.

The army denies the EIA protocol was breached. In a press conference organized at the army headquarters on Feb 23, Brig. Gen. Bikash Pokharel, the fast track project chief, dismissed our finding that trees at Bandarkholchha had been felled. He even refused to accept our photographic evidence.

Pokharel instead claimed the fast track had created jobs for those living near project sites.

“For every Chinese worker, there are three Nepalis employed at the project sites,” he told the assembled media representatives. “Chinese workers, moreover, teach useful skills to their local counterparts.”

But the people we spoke to had a different experience. Most of them were unhappy with the way the army was managing the project. They said very few villagers were employed.

“Although this mega project has come to our village, we are not getting the promised jobs,” says Dinesh Moktan of Bakaiya Rural Municipality in Makawanpur. “We asked the army for more local participation, but our plea was ignored.”

There is still a lot of work to be done before the new fast track deadline of 2024 (the previous deadline was November 2021). The army itself reports 16.1 percent overall progress. Experts warn of further time and cost overruns. Some even question the idea of handing over fast track construction to Nepal Army. Their concerns emanate from alleged irregularities in the project that have cropped up time and again since the government commissioned the task to the army in 2017.

Semant Dahal, a lawyer who has closely studied the project, believes time has come to ask some hard questions. Given the paucity of progress in the past five years, “Do we still think it [the Army] is the most suitable entity to build such an infrastructure project?” he questions.

Also read: ApEx Explainer: The what, where and when of the fast track

In 2019, a probe had found that the evaluation criteria for the selection of consulting firms for the project had been leaked to potential bidders. The decision to select six international companies was scrapped over the leak, which the army termed a “technical error”.

The following year, a government review committee opened an investigation into the army’s alleged breach of the Public Procurement Act when it selected a Korean company as a project consultant.

Fast track construction was handed over to the army following an earlier controversy over the government’s decision to award the contract to Infrastructure Leasing & Financial Services (IL&FS) of India in 2014. The contract dispute had reached the Supreme Court and the deal was ultimately ditched.

Meanwhile, the army was lobbying to secure the contract despite having no prior experience of working on large infrastructure projects.

The 2017 decision to award the project to the army had gotten a favorable response from experts and public alike. After all, it was the army that had opened the track for the expressway. Five years later, the army’s role is increasingly coming into question.

Experts and stakeholders are demanding transparency and accountability from the army as the project has run into delays and controversies. The fast-track cost, which was estimated at Rs 86 billion in 2011, has soared to Rs 213 billion. The army is in no place to assure that the project will be completed within the new deadline and reasonable budget.

The army’s lack of experience in big projects is perhaps a reason the fast track has been facing hiccups and delays.

Further, some say the schooling and institutional attitude of the army hasn’t changed much since the 90s—as the army was back then, it is still largely unaccountable to the authorities.

There have been numerous complaints against the army’s flouting of the instructions of parliamentary committees and other government bodies.

Also read: Fast track, off track

Bharat Kumar Shah, chairman of the Public Accounts Committee of Parliament, says the army just does not listen.

“We had asked the Nepal Army to halt bridge and tunnel works following some discrepancies in the bidding process, but it simply brushed aside our directive,” says Shah.

The army is also not helpful when it comes to sharing information, or supporting independent inquiry. Our team was repeatedly accosted and questioned by the army in the course of reporting at fast track sites. They demanded a permit from army headquarters to take photos at some sites—all public places.

Many experts ApEx spoke to (many of whom chose to remain anonymous) say that in retrospect giving the fast track to the army was a bad decision. They suspect the project was handed over to the army to avoid controversies, with most people trusting the institution to do the right thing.

Brig. Gen. Narayan Silwal, the army spokesperson, denies the allegations against the army. He says talks of the expressway being further delayed and incurring more money are all misinformed rumors.

“The national pride project is being built under the management of a disciplined institution,” he insists.

Few women in federal, provincial executive bodies

Females make up 51.04 percent of Nepal’s population, but their representation in government bodies is much lower. This means their issues and concerns are rarely addressed.

Every year on March 8, various government agencies working on women rights and empowerment mark the International Women’s Day. They announce campaigns and programs for women rights and representation and yet they invariably fail to achieve the desired results.

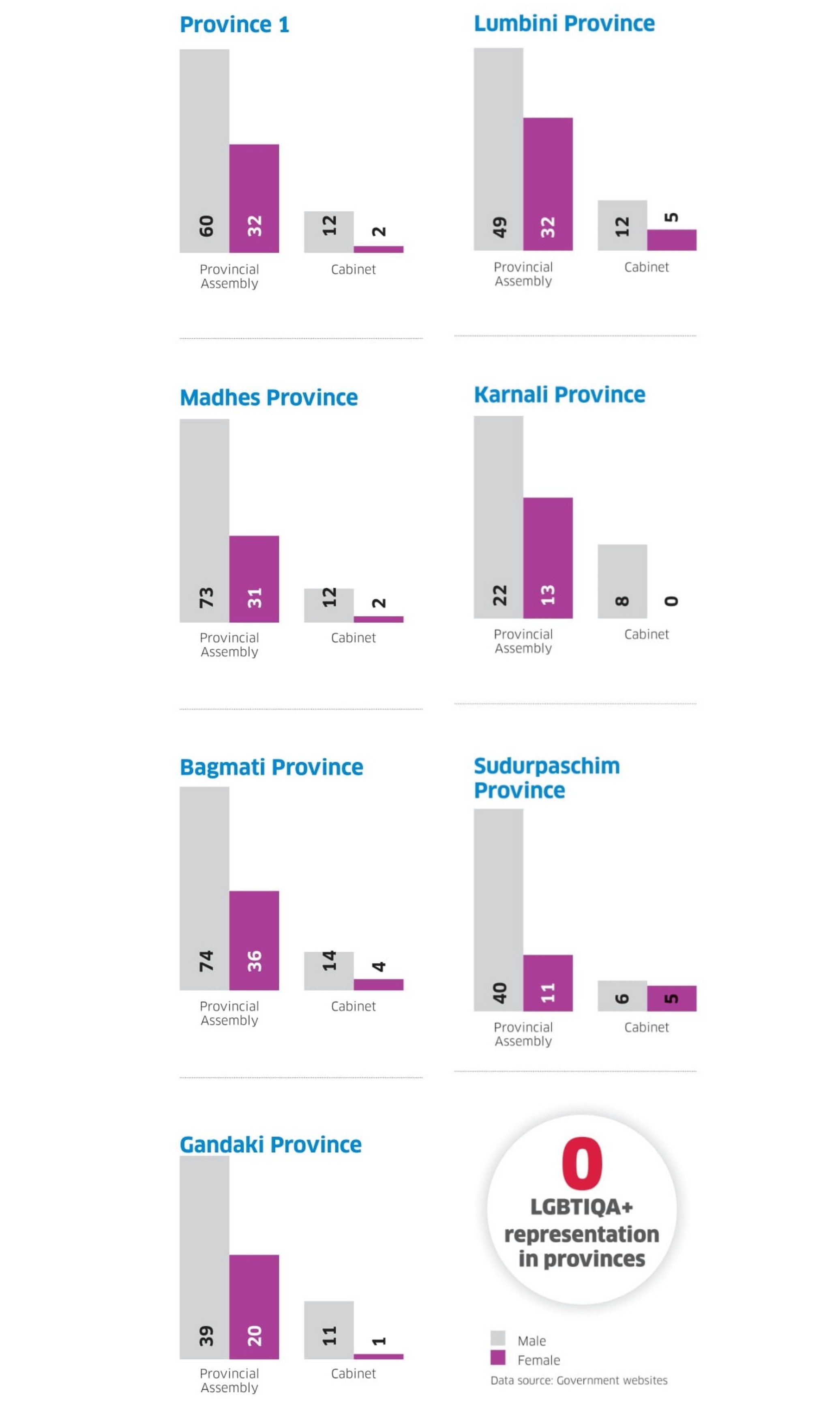

Nepal’s constitution mandates a minimum 33 percent women representation in legislative bodies. As a result, the federal parliament fulfills the women representation criteria—33.7 percent in the House of Representatives and 37.28 percent in the National Assembly—and so do the provincial assemblies.

But in executive bodies, women are heavily underrepresented. In the federal council of ministers, women representation is 26 percent; provincial ministries are also dominated by male ministers.

This shows that significant (if still inadequate) women’s representation in legislative bodies owes solely to constitutional provisions and not a commitment to leveling the playing field.

Province 1 and Madhes have 14.28 percent women representation in their cabinets, whereas Bagmati and Lumbini have 22.22 percent and 29.41 percent women representation respectively. In Gandaki province, women ministers comprise eight percent of the cabinet and Karnali has no female minister.

While Sudurpaschim province has 45.45 percent women representation in the cabinet, its legislative assembly has just 21.56 percent women.

Bimala Nepali, lawmaker and member of Women and Social Affairs Committee of Parliament, says they have repeatedly urged the government to at least ensure a minimum threshold of women in the federal Cabinet, to no avail.

More men should take up women’s rights advocacy

Bimala Rai Poudel

Member of National Assembly

I ask for 51.04 percent women representation in every sector, in line with our population data. Currently, our legislative bodies have a decent number of female representatives, and we can raise our issues more effectively. But we also need men on our side. Gender equality should be a universal cause. To build an equal society, it is imperative that men take up the issues of women’s rights and representation.

Jayananda Lama obituary: A multi-talented artist

Birth: 27 July 1955, Sindhupalchok

Death: 23 February 2022, Bhaktapur

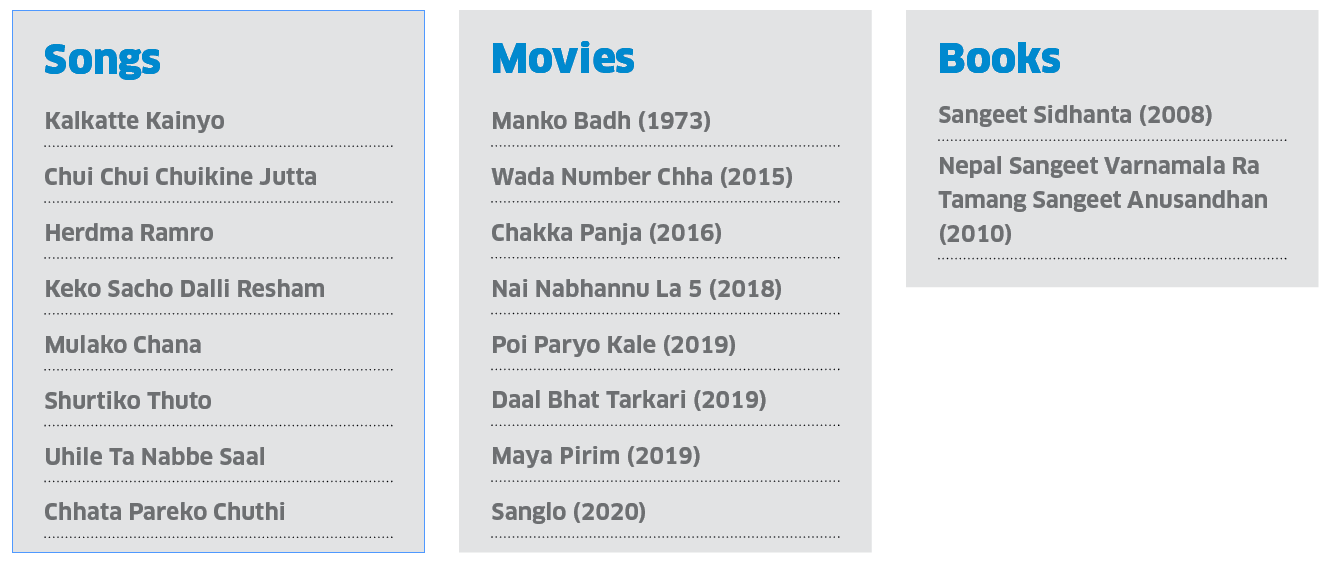

Jayananda Lama, who died aged 66 on February 23, was a man who wore many artistic hats: he was a singer, dancer, music scholar, movie producer, director and actor.

The voice behind ‘Kalkatte Kainyo’, a popular Nepali folk song, and ‘Keko Sacho Dalli Resham’, a ditty popularized among modern music listeners by blues-rock group Mukti and Revival, Lama initially started out as a dancer before making his name in music and acting.

Lama was a 12-year-old boy growing up in Sindhupalchok when he was discovered by Bhairav Bahadur Thapa, a veteran choreographer and dance scholar who was scouting for musicians and dancers from across the country.

The young Lama came to Kathmandu where he was schooled and trained under Thapa’s tutelage. He became a member of Bhairav Nritya Dal, the country’s first cultural troupe established by Thapa and playwright Balkrishna Sama. Lama’s contemporaries at Bhairav Nritya Dal included actor Hari Bansha Acharya and singer and musician Ram Thapa. The eclectic circle of friends, each talented in a different field of performance art, had a great influence on Lama. He also learned to sing and play musical instruments.

As a little boy, Lama participated in a national cultural competition organized to mark the 46th birthday of the then king Mahendra. His performance won him a consolation prize of Rs 1,000 and a deal to record four songs at Radio Nepal. His first song ‘Roko Manalai Bujhaune Ko Hola?’ was recorded in 1967.

The competition was a turning point in Lama’s life. His performance had impressed the king and other royal family members. After the show, King Mahendra and the crown prince at the time, Birendra, praised Lama and offered to pay for his studies. He would get to know the royal family more intimately in the future.

Lama continued his schooling and training at the Bhairav Nritya Dal. With his fellow dancers, singers and musicians, he toured different parts of the country and abroad for shows.

Lama had a BA degree in Music from Lalitkala Campus, Bhotahiti. After getting the degree, he got a job at Nepal Academy (Royal Nepal Academy at the time). He also became a music teacher for the then crown prince Dipendra.

While at the academy, Lama got his master's degree in Music from Allahabad, India. Not long after his return from India, he joined Radio Nepal with the intent of promoting Nepali folk songs and artists. At the Radio Nepal studio, Lama recorded his own numbers and promoted other folk musicians like Narayan Rayamajhi.

Artists who worked with Lama remember his collaborative spirit, humility and contribution to promoting and popularizing folk songs. He recorded more than 200 songs during his lifetime. His song catalog was instrumental in the launch of Music Nepal, the country’s first music company.

Lama also worked as a lecturer of music at Tribhuvan University for four years and traveled across Nepal researching and collecting local folk music. His research led him to write two related books. At the time of his death he was working on his third book, on Pingul script, the oldest Nepali folk music script.

A man of many talents, Lama was also an actor—a prolific one. Since his debut movie ‘Manko Badh’ (1973) he went on to appear in over 100 films and TV shows. Although he dabbled in producing and directing films and TV series, he was best known for his acting.

He was mostly cast in comic roles, which he portrayed deftly. The smash hits ‘Chakka Panja’ (2016), ‘Nai Nabhannu La 5’ (2018), and ‘Poi Paryo Kaley’ (2019) are among his popular films.

Lama had been making more TV and film appearances in recent years.

Although he participated in musical events and TV shows like ‘Nepal Lok Star’, a singing reality contest for folk singers, he had not recorded his own songs in decades. In several interviews, Lama had expressed his discontent with the current folk music scene. He had come to despise the brazen vulgarity seeping into modern folk songs in the name of producing commercial hits and he didn’t want to sing anymore.

He was all about preserving and promoting folk roots and traditions.

Lama did make a comeback from his long musical hiatus by releasing a song a couple of months ago before his death. In one interview he had even said that he had collected enough songs to keep crooning for the rest of his life.

Lama is survived by his wife and two sons.

Fast track, off track

In its Feb 22 press meet, Nepal Army insisted that work on the 72.5-km Kathmandu-Tarai fast track was on track despite a few hurdles. It assured things would pick up pace in the second half of 2022 and the project would be completed by Jan 2025. (The initial deadline was Sept 2021.) Yet ground realities suggest otherwise.

An ApEx team recently set out to document progress on the project, visiting many places along the 72.5km-track length. We spotted many problems. Many locals of Khokana in Lalitpur, the road’s starting point, are still vehemently against the project, insisting that money is not what they want. They say no amount of money can force them to give up their ancestral lands. Then in the stretch in Makawanpur district, we could see stumps of countless felled trees even as there was no other visible progress.

As economist and ex-Nepal Planning Commission member Chandra Mani Adhikari pointed out in a recent ApEx roundtable on the topic: “In 2009, JICA had estimated the project cost at Rs 86 billion. In 2022, the estimated cost has reached a staggering Rs 213 billion”. The cost, Adhikari adds, will continue to balloon if works are not expedited.

Also speaking at the roundtable, Semanta Dahal, a lawyer and researcher, said time had come to ask some hard questions. Given the paucity of progress in the past six years, “do we still think the army is the most suitable entity to build such an infrastructure project?” he asked.

This newspaper will try to capture multiple aspects of the project in its 10-part ‘InDepth’ series (of which the roundtable this week is the second part). The goal is to bring some clarity to this otherwise opaque endeavor.

ApEx roundtable on Kathmandu-Tarai fast track

ApEx recently hosted a roundtable with a group of experts on the Kathmandu-Tarai Fast Track Project. The objective was to understand the many aspects of the project—its current status, its cultural and environmental impacts, and the lessons we have learned from it. Here are excerpts of the opinions shared in the roundtable.

(Note: Nepal Army, which has been commissioned to develop the project, didn’t send its representative to the roundtable despite repeated requests.)

Aasha Kumari B.K.

Lawmaker and member of Development and Technology Committee of Parliament

In May 2021, army officials and our committee had officially discussed the fast track. That time local residents around project sites had complained to us that there was no one to listen to their concerns. So the committee had directed the army to build camps at different project sites to address local concerns. The army now has 10 such camps, which is a positive development. We are also planning another meeting with the army, as the residents living near the project sites have reported some new environment-related concerns. We have gotten reports of environmental damage and dust at project sites affecting the health of local residents.

And there is the issue of compensation. Nepal Army hasn’t been able to settle compensation for land acquisition in Khokana, Lalitpur, as some of its residents want to be compensated at updated land rates. This issue has become particularly thorny as some residents have already accepted compensation at previous rates. The army has asked the government for additional funds to resolve the land dispute. In our upcoming meeting, we will try to work out the best solution.

Dr Chandra Mani Adhikari

Economist and a former member of National Planning Commission

In 2009, JICA had estimated the project cost at Rs 86 billion. In 2022, the estimated cost has reached a staggering Rs 213 billion. The cost will continue to rise if works are not expedited. The most-used highway that connects Kathmandu with the Tarai is around 270 km. When the fast track comes into operation, it will shave off a distance of around 200 km. This will benefit us economically. We can expect commodity and fuel prices to come down with the fast track, largely because of lower transport costs. With the fast track in place, we can also use the dry ports at Birgunj and Chobhar to their maximum capacity.

Developed countries invest in infrastructure and connectivity projects, which they consider their economic lifelines as they give fast turnovers. We must learn from them and start investing in such projects.

I also doubt the decision to hand over the fast track to Nepal Army that has no experience of dealing with such mega-projects.

Parbati Kumari Bishunkhe

Lawmaker and member of Public Accounts Committee of Parliament

As Nepal Army did not have the necessary equipment and manpower to undertake the project alone, it hired other international companies to work on many of the project components. Complaints have been filed with the Public Accounts Committee that some of these companies were hired without following due process. The committee has already taken up this matter with the army. It has been reported that the army needed two companies to build the track’s inner channels, and invited tenders accordingly.

For the first channel, there were only two interested companies and one of them was selected. But on the tender for the next channel, 21 companies had applied. There have been complaints that the army prepared the Performance Qualification (PQ) questionnaire favoring one particular company, which ultimately got the contract.

We plan on inquiring into this as soon as parliament procedures stabilize.

Sanjay Adhikari

Public interest litigator for natural and cultural heritage

Khokana and Bungmati are ancient villages attached to the Newa civilization. The fast track project is endangering their cultural and historical significance. In the name of development, the government is trying to drive away the native Newa families who have been living there for ages.

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, of which Nepal is a signatory, as well as our constitution, advocate for the rights of indigenous people. But we are not following them.

We have requested the National Human Rights Commission to intervene on behalf of Khokana and Bungamati residents, but to no avail.

Semanta Dahal

Lawyer and researcher

Nepal has to invest almost 13 to 15 percent of its GDP in infrastructure projects for the next two decades to meet its development goals. On highways and roads alone, we needed to allocate around $1.3 billion in 2020 but there was a gap in required financing. Going by this trend, we can estimate that the country will require $5.6 billion by 2025, and $7.5 billion by 2030. Will the government alone be able to allocate such large sums? No. So private investment is necessary to bridge the infrastructure gap if we want to develop mega roads and highways.

But the government has failed to create an investment-friendly climate. Except in hydropower, it has been unable to encourage private companies to invest in other public infrastructure projects despite the passing of the Public-Private Partnership (PPP) legislation. Separately, one thing we must ask based on time that has already elapsed since Nepal Army was assigned to develop the fast track in 2015 is: Do we still think it is the most suitable entity to build such an infrastructure project?

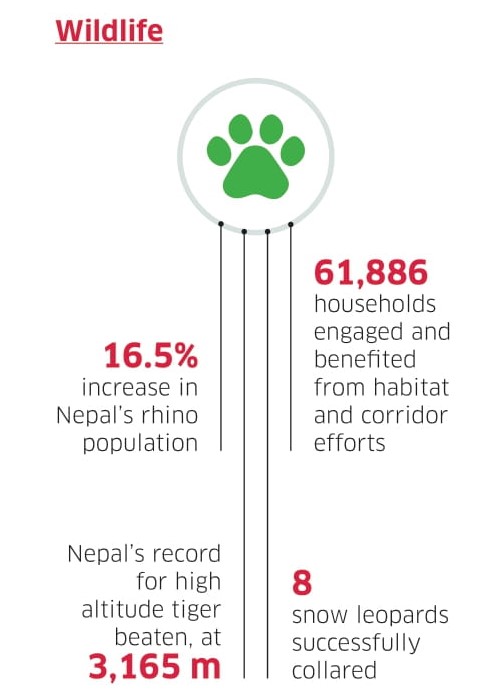

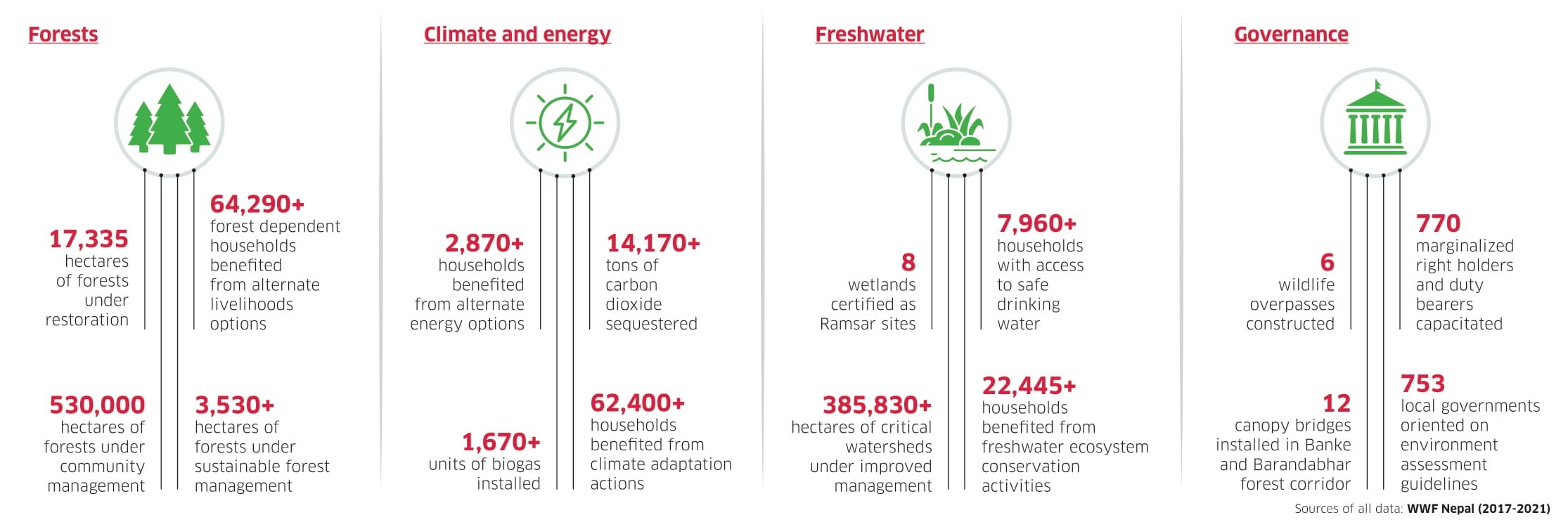

Nepal’s progress in wildlife conservation

WWF Nepal in 2021 ended its USAID-funded Hariyo Ban Program after 10 years. In this period, the program achieved several conservation milestones.

Nepal is on track to achieving the global goal of doubling its tiger numbers as it has recorded tigers at altitudes of 2,500 meters in the west and 3,200 meters in the east.

Similarly, the one-horned rhino count has hit a historic high with 752 counted last year (694 in Chitwan, 38 in Bardiya, 17 in Shuklaphanta and three in Parsa), in what was a 16.5 percent increase from 2015. Nepal also collared two additional snow leopards in Shey Phoksundo National Park.

When covid pandemic led to illegal logging, forest product harvest and wildlife crimes, the program in partnership with government, local communities and stakeholder renewed its efforts to protect forests and wildlife. WWF Nepal alone contributed to the protection of 161,813 hectares of forests by strengthening Forest Conservation Areas (FCA). Also, the authorities concerned maintained guard posts, fire lines, revised policy assistance, and held transboundary meetings with the Indian side to develop a cross-border sharing mechanism.

Efforts were also initiated to reduce fuelwood as the primary source of energy, as it hampers the environment along with the health and safety of communities.

Climate change was another field where the Hariyo Ban Program was active. Climate change has affected multiple small communities in the form of climate-induced disasters such as flooding and riverbank erosion.

To address these problems, the Climate Change Strategy and Action Plan (CCSAP) for each province of Nepal is currently being prepared to localize the National Climate Change Policy that aims to make a transition to 100 percent renewable energy.

Overfishing, proliferation of aquatic invasive species, unmanaged sand and gravel mining, pollution, encroachment, siltation, unplanned infrastructure development and ground water extraction continue to threaten freshwater ecosystems. To cope with these challenges, seven artificial wetlands were constructed and restored in the western Tarai. These wetlands are expected to retain around 200 million liters of underground water.

There has also been work on strengthening indigenous people and local communities’ access to natural resources and ensuring equitable benefit sharing mechanisms by creating transparent, participatory, inclusive governance mechanisms for sustainable management of natural resources.