Nepal’s economy shows no signs of recovery

Nepal’s economy is struggling due to depleting foreign exchange reserves and soaring inflation. It has approached international financial institutions for a bailout, joining the likes of Pakistan and Bangladesh, who too are hard-pressed to shore up their faltering economy. As a measure to maintain its forex reserves, the Nepal government has curbed the import of so-called luxury items.

As a result, according to Nepal Rastra Bank, imports shrank by 12.9 percent between Aug 15 and Sept 19. Meanwhile, remittance inflows have increased by 20.3 percent to Rs 92.21bn in the review period against a decrease of 17.4 percent in the same period last year. Officials say while foreign currency reserves are still going down, thanks to the import restrictions, they are sufficient to last for prospective merchandise import of 9.4 months, which had fallen to six months in March. But Nepal is not out of the woods yet.

Economist Chandra Mani Adhikari says there is still a risk of a full-blown economic crisis, as all parameters have not been performing well. “Merchandise exports are still surging which is likely to go up during the upcoming festival season,” he says. “Then there is the November election that could further strain the economy.”

Economist Dilli Raj Khanal is also not hopeful about economic recovery in the immediate future. “The stopgap measure of restricting import cannot sustain for long.” The private sector warns that prolonging import restrictions could discourage foreign investment and fuel unemployment, thus hurting the economy even more. Ramping up domestic production and export is one way to save the economy.

Current scenario

· Inflation stands at 8.26 percent

· Imports decreased 12.9 percent, exports decreased 28.7 percent

· Trade deficit decreased 10.4 percent

· Remittances increased 20.3 percent and increased 12.5 percent in USD terms

· Balance of payments remained at a deficit of Rs 22.63bn

· Gross foreign exchange reserves stand at $9.42bn

· Federal Government spending amounted to Rs 22.26bn

· Revenue collection Rs 79.72bn

ApEx Series: Is ropeway revival possible?

This year marks the centenary of the start of ropeway in Nepal. Renewable Energy Confederation of Nepal (RECON), Nepal Ropeway Association, USAID and other relevant institutions are planning to celebrate the 100 years by holding seminars on the importance, relevancy, and revival of ropeway technology in Nepal. They are planning to conduct the seminars in all seven provinces and invite the concerned government representatives. They hope these events will push the government authorities to rethink the revival of ropeway transport in Nepal.

The government so far has shown no interest in developing ropeway system in Nepal. Tulsi Gautam, spokesperson for the Ministry of Physical Infrastructure and Transport, says, “The government as of now has no plans to commission a ropeway project on its own.” This is despite the fact that the government is aware of the ropeway’s potential in Nepal and its suitability in terms of both cost and practicality.

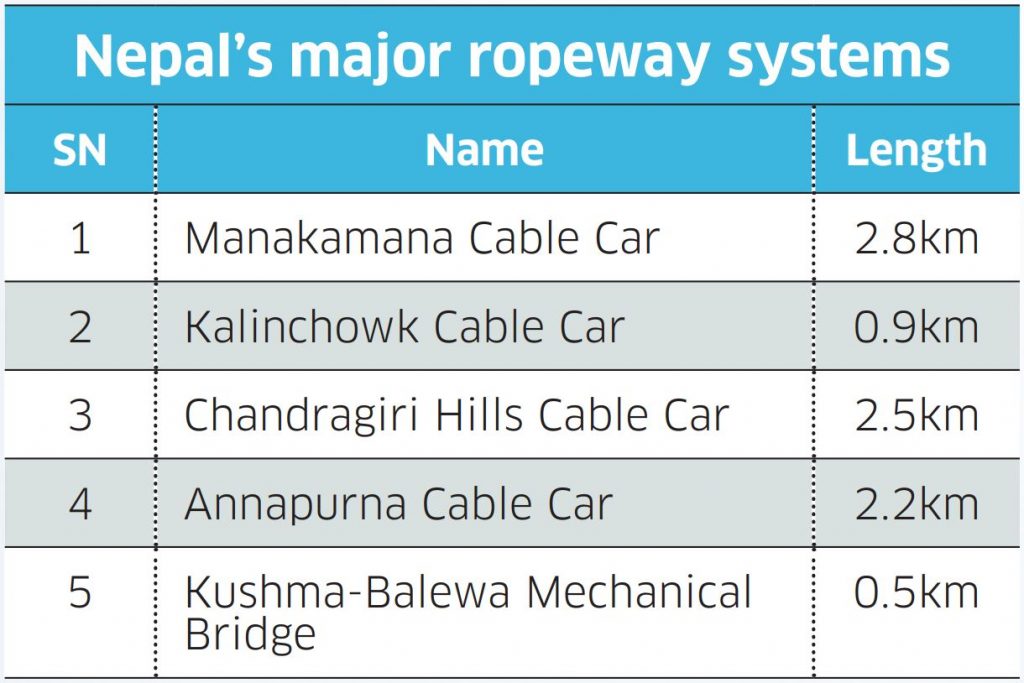

Several studies on ropeway potential in Nepal suggest the country could have ropeway transports in nearly 2,000 areas and feasibility studies have also been conducted in 62 of these locations. To date, there are only five ropeways for human transport and almost a dozen gravity goods ropeways are in operation in Nepal. The book ‘Ropeways in Nepal’ by Dipak Gyawali, Ajaya Dixit, and Madhukar Upadhya recounts many past success stories of Nepali ropeway projects, but the idea of developing ropeways to ease the problem of transporting goods and humans has simply not registered on the minds of the government officials and ministers.

“The fact is the government officials and ministers do not get much commission from ropeway development unlike road projects,” says Gyawali, who is also a former water resource minister. After the success of pioneering ropeway projects, the government incorporated plans and policies for improving and extending the existing ropeway services in the fifth Five-Year Plan. With grant assistance from the US government, the old 22-km long, low-capacity mono-cable system between Dhorsing and Kathmandu was replaced and extended with a 42-km-long bi-cable ropeway between Hetauda and Kathmandu. The sixth Five-Year Plan proposed developing gravity ropeways in the hills and mountains to transport daily goods and Rs 6m was allocated to execute the plan, but nothing came of it.

After the restoration of multi-party democracy in the 90s, the eighth Five-Year Plan incorporated ropeway under the sub-sector of ‘other modes of transport’ and announced a program for consolidating the existing ropeways and operating them at full capacity. There was also the plan of encouraging the private sector for the development of short-haul ropeways to promote tourism as well as developing gravity ropeways. For these purposes, the government of the time allocated Rs 158m. The next national plan announced a more ambitious 20-year National Transport Master Plan that included a cable car/ropeway development program and privatization of ropeway transports so that they could be operated more effectively.

The approach paper of the 10th Five-Year Plan (2002-2007) again stated that policies for developing ropeway transportation would be adopted. It also set the aim of encouraging private entrepreneurs to construct and operate cable car/ropeways in places with importance for tourists and local economies where road access is lacking. Priority for cable car/ropeway development would be accorded to those areas where the cost of constructing and operating roads would be comparatively high.

Experts say though policies and modest-scale programs were incorporated in Nepal’s Five-Year Plans, the progress over the years have been slow. In fact, they add, the ropeway development plan has more or less remained stagnant since 2007. Its potential to become an important segment of the country’s transport system was not realized. Post 2007, the Five-Year Plans had no mention of policies on ropeway development.

Upadhyay, the co-author of ‘Ropeways in Nepal’, says Nepal is in the 15th Five-Year Plan, but for the last two decades, there has not been any progress on ropeway development. Like Gyawali, he too is the view that the political leadership is deliberately ignoring the ropeway potential because they do not get any financial gains. “If the government ministers and politicians agree to build ropeways instead of roads, they cannot earn commissions.” Upadhya, who was in-charge of building the Bhattedanda ropeway, adds unlike ropeways, roads need to be maintained regularly, which brings in large funds for politicians and contractors.

Experts say ropeways can be a viable solution for not just transporting goods and people, but also in the process of managing municipal waste. Guna Raj Dhakal of Ropeway Nepal Pvt Ltd says the system could be utilized to transport the waste generated in Kathmandu Valley. “There has even been a study on this issue, but there was no follow up. The plan never took off.”

Gyawali says the ‘Ropeway in Nepal’ was launched in presence of the then ministers and officials from the National Planning Commission (NPC) and that they know the ropeway could transform Nepal, but they are still not comfortable with the idea. “This simply reflects the unwillingness of the government towards sustainable and cost-effective development ideas,” he adds. To date, the NPC has not started any discussion on the feasibility of ropeways. Asked why, the commission member, Uma Shankar Prasad had no answer.

The new challengers

Call it ‘Balen effect’ or ‘Sampang effect,’ many young and educated people have declared their independent candidacies for the November elections, and the old-established parties feel unsettled. The groundswell of urban voters’ support to independent candidates in the May election has made parties realize they cannot risk fielding political stooges and placement in the upcoming polls.

Anthropologist Laya Prasad Uprety says the wave of independent candidacies in local and national elections is a sign that Nepali voters, mostly youths, are deeply disenchanted with the established political parties. “Since 1990, Nepali political parties have failed to work for the interest of people. And many of today’s young generation see these parties and their leaders as part of the problem,” says Uprety. “That is why we are seeing a rise in independent election candidates.” Political analyst Lok Raj Baral has a different thought regarding the rise in independent candidates.

He says there is a significant difference between local and federal elections. “Yes, the effects of Balen and Sampang’s victory in the local elections might sway some voters to pick independent candidates, but it cannot make that much of a difference to hurt the established parties.”

Full story here.

Balen and Sampang effect in federal elections

On Aug 29, CPN (Maoist Center) Chairman Pushpa Kamal Dahal said at a public function that his party was seeking candidates who could gain sentimental votes in the November 20 elections to the federal and provincial assemblies. “Balen won the same way,” he said, referring to the unprecedented victory of the incumbent Kathmandu mayor in the May 13 local polls.

The rapper turned independent mayoral candidate, Balendra Shah had defeated the candidates from major political parties. Following Dahal’s remarks, there was a rumor that the Maoist party was considering Kulman Ghising, managing director of Nepal Electricity Authority, who is credited for resolving the problem of perennial power cuts in the country, as one of its candidates for the November polls. Ghising has since refuted the rumor, but there is a deep significance to Dahal’s statement.

Call it ‘Balen effect’ or ‘Sampang effect,’ many young and educated people have declared their independent candidacies for the November elections, and the old-established parties feel unsettled. The groundswell of urban voters’ support to independent candidates in the May election has made parties realize they cannot risk fielding political stooges and placement in the upcoming polls.

Suman Sayami has declared his candidacy for a federal parliament seat from Kathmandu-8. He is a prominent Newa rights activist and heritage conservationist, who had also run as an independent mayoral candidate for Kathmandu Metropolitan City back in May. He says Nepali people want progressive, independent candidates who can establish rule of law and good governance.

“The victory of Balen and Sampang in the local polls reflects the desire of Nepali voters.” Sayami is also the coordinator of ‘Lauro Campaign’, a loose alliance of independent candidates who have been lobbying to get ‘Lauro’, the election symbol of Balen and Sampang, as their election symbol for the November polls. Pukar Bam, another independent candidate from Kathmandu-1, says the outcome of local elections in cities like Kathmandu and Dharan show that people are tired of traditional political parties.

“The local elections have encouraged many young people to contest in the federal elections as independent candidates,” he adds. Bam was a campaigner for the ‘Enough is Enough’ protest movement against the KP Oli government’s poor handling of the Covid-19 pandemic. He believes there is a good winning probability for independent candidates after they have agreed to form alliances in some constituencies. “Previously, there were over two dozen independent groups who were planning to contest the upcoming elections,” says Bam. “After we agreed to forge alliances, the number has come down to three.”  Sagar Dhakal is another hopeful independent candidate, who has declared his candidacy from Dadeldhura-1, the hometown of Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba. Dhakal, who came to limelight after a heated exchange with Deuba on live TV in 2017, is a hydro-mechanical engineer by profession. He says Balen and Sampang have offered hope to Nepali people that all is not lost. “Every step of Balen and Sampang is being discussed by people in all corners of Nepal,” he says.

Sagar Dhakal is another hopeful independent candidate, who has declared his candidacy from Dadeldhura-1, the hometown of Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba. Dhakal, who came to limelight after a heated exchange with Deuba on live TV in 2017, is a hydro-mechanical engineer by profession. He says Balen and Sampang have offered hope to Nepali people that all is not lost. “Every step of Balen and Sampang is being discussed by people in all corners of Nepal,” he says.

“This is entirely a new phenomenon and it gives hope and encouragement to independent candidates.” Political analyst Lok Raj Baral has a different thought regarding the rise in independent candidates. He says there is a significant difference between local and federal elections.

“Yes, the effects of Balen and Sampang’s victory in the local elections might sway some voters to pick independent candidates, but it cannot make that much of a difference to hurt the established parties.” He believes that if someone is going to change Nepali political culture that is independent groups who are not affiliated to any established political parties. Aakarshan Pokharel, a civil engineer turned politician has already announced his candidacy in Kathmandu-4, against the general secretary of the Nepali Congress Gagan Thapa.

“Balen and Sampang gave Nepali people a hope, an alternative to traditional political parties,” says Pokharel. “These two mayors are being widely hailed by the public. The perception of voters towards independent candidates has changed.” Arnico Panday, an independent candidate from Lalitpur-3, also gives credit to Balen and Sampang for his decision to run in the November elections. “I had thought of contesting in parliamentary elections before, but I was hesitant then. The rise of independent candidates has given me confidence.”

Panday is an expert on environmental science and public policy. It is important for Panday and his fellow candidates that Nepali people outvote the old, outdated political candidates. They want the candidates with a clear vision to win, not those with unnecessary political agendas. “Nepal needs people-centric leaders.” Balen and Sampang have also proved that election campaigning should not necessarily be an expensive affair. They believe that the most important thing is for the candidate to connect with the voters by visiting their homes and neighborhoods. “I am not in favor of expensive election campaigns and promotion,” says Dhakal. “I am instead visiting the communities in my constituency and explaining my agendas to them.”  Anthropologist Laya Prasad Uprety says the wave of independent candidacies in local and national elections is a sign that Nepali voters, mostly youths, are deeply disenchanted with the established political parties. “Since 1990, Nepali political parties have failed to work for the interest of people. And many of today’s young generation see these parties and their leaders as part of the problem,” says Uprety. “That is why we are seeing a rise in independent election candidates.”

Anthropologist Laya Prasad Uprety says the wave of independent candidacies in local and national elections is a sign that Nepali voters, mostly youths, are deeply disenchanted with the established political parties. “Since 1990, Nepali political parties have failed to work for the interest of people. And many of today’s young generation see these parties and their leaders as part of the problem,” says Uprety. “That is why we are seeing a rise in independent election candidates.”

Uprety, however, adds that the global historical precedence suggests that independent candidates could never become an alternative to established political parties. “At the moment, young Nepalis think voting for independent candidates is the way to go, which I wholly support, but in the long run, we need political parties.” Uprety says the voting pattern this time will be different than previous elections, as the result of local elections has projected few independent wins in federal polls. “The established political parties have already realized this. We have to see how they will pick their candidates.”

Manushi Yami Bhattarai, who has been lobbying for her candidacy from Kathmandu-7, is happy with emerging independent candidates. “This trend has rattled the major political parties, which is a good thing.” Bhattarai, who is the daughter of former Prime Minister Baburam Bhattarai, believes if independent candidates were to win in the upcoming elections, political parties will be forced to improve. “I believe in a multi-party democracy, but I also support independent candidates,” she says. “It will help our democracy.”

ApEx Series: Let there be ropeways

Ropeways are an ideal means of human and goods transport in Nepal, a country filled with rugged mountains and hills. In fact, installing ropeways are six times cheaper than building roads. Yet there has been little interest in their development. Studies suggest Nepal could have up to 2,000 ropeways and feasibility studies have been completed on 62 of them. So what accounts for the paucity of ropeway carriages zipping over our hills and valleys?

The lengthy bureaucratic process is one problem. For instance, for an investor to build a ropeway, he or she has to get permits from 21 different government agencies. Cable cars—of the kind we see in Manakamana and Chandragiri—are also a kind of ropeway. The Manakamana cable car was first established in 1998. Quickly, the economy and job prospects of the surrounding areas were transformed. There could be no clearer case of a high social return on investment. Yet it would be another two decades before another cable car company came into operation. Surprisingly the government has taken no initiative to expand the reach of ropeways and cable cars. Private companies are doing all the heavy lifting.

This is a case of misplaced priorities. Politicians have forced people to see longer and wider roads as synonymous with development, despite the enormous environmental and financial costs incurred in the process. The cable car system could also be mighty useful in urban hubs. “Our politicians have been pitching for metro-rail and monorail to ease Kathmandu valley’s traffic congestion,” says Guna Raj Dhakal, chairperson of Ropeway Nepal Pvt Ltd. “But a cable car system could address the problem of urban mobility even better.” There is also ample scope, all around Nepal, for the ropeways that exclusively transport goods. Unlike the people-carrying cable cars, they don’t need that many permits to operate as well.

Read full story here.

Rudra Neupane: The brain behind Run Shoes success story

Rudra Neupane, 44, comes from a farming family background in Sindhupalchok. His village was at a remote part of the district, where there were no schools until the 1980s. Neupane went to school fairly late in his life and came to Kathmandu in 1994 for higher studies. In 1997, he was called back to his village to vote in the local elections, but he remained there for five years.

“I had gone home to vote but I stayed there after I was offered a teaching job in the high school that I attended as a child,” says Neupane. “Later on, I quit teaching and started working at the District Development Committee as a social mobilization officer.” He got married in 2001 with his wife, who was also a teacher. Neupane says his wife didn’t didn’t like the teaching field and wanted him to find another line of work. His work as a social mobilization officer, though a government job, was a temporary one, so he wanted to find a good stable employment.

“But finding a job was challenging back then,” Neupane says. “The difficulty in finding a decent job made me realize that I should rather start my own business and create jobs for others.” The couple decided to start a business but they had no promising entrepreneurial idea. They analyzed the market and consulted with friends and relatives. Neupane’s maternal uncles were already in the trade business, but it was not what he wanted.  “I was more inclined into agriculture-related business because of my farming background.” The agriculture-based business never panned out. The couple instead started Run Shoes Industries, a footwear company, in 2012. Neupane says the idea for the company came to him while working with footwear wholesalers to support his family in Kathmandu.

“I was more inclined into agriculture-related business because of my farming background.” The agriculture-based business never panned out. The couple instead started Run Shoes Industries, a footwear company, in 2012. Neupane says the idea for the company came to him while working with footwear wholesalers to support his family in Kathmandu.

“Had those footwear wholesalers not supported me technically and financially, I could not have started this company,” he says. “So all the thanks and gratitude go to them.” Neupane started Run Shoes with an investment of Rs 20m and within a couple of years, expanded the company’s footwear market across Nepal. The company is now worth Rs 500m, according to Neupane’s own estimates. The company owns two footwear factories in Bode, Bhaktapur, and in Mulpani, Kathmandu, and employs 250 workers.

In the early days, Run Shoes used to import soles for its footwear from China, Singapore and South Korea but today, the company itself produces the soles and other parts. “The only thing we import is the raw materials to make soles,” says Neupane. With the success of the footwear business, Neupane is also branching out to other areas of business. He has also started a garment factory and is involved in a couple of hydropower projects.

Besides, he is also working toward realizing his long-held dream of starting an agro-based company. “The company will not be for profit. It will be there just to facilitate farmers and provide them with good tools and technologies.”

ApEx Series: High in potential, low in execution

Five ropeways for human transport and almost a dozen gravity goods ropeways are in operation in Nepal. Ropeways are an ideal mode of human and goods transport for Nepal’s hill- and mountain-dominant terrains. Their potential, however, is yet to be fully realized. Reports suggest that the country could have ropeways in nearly 2,000 areas and feasibility studies have been conducted in 62 places. But to install a ropeway for people transport in Nepal, an investor has to get approval from 21 different government authorities.

“We’ll not attract investors unless our bureaucratic hurdles are simplified,” says Guna Raj Dhakal, chairperson of Ropeway Nepal Pvt Ltd. Installing ropeways is six times cheaper than building roads and the maintenance cost is also low. The 42-km Hetauda-Kathmandu Ropeway, for instance, cost half as much as the Tribhuvan Highway on the same route to build. “Yet the government is still skeptical about ropeways,” adds Dhakal. “We don’t even have a dedicated ropeway department or policies for that matter.” When CPN (Maoist Center) joined mainstream politics after signing the Comprehensive Peace Accord in 2006, the party committed to installing around 50 government-run ropeways in its first election manifesto. The party has been in almost every government since, but the old promise is yet to be fulfilled.

Haribol Gajurel, the party’s deputy general secretary, blames political instability for this state of affairs. “Our party led the government only twice and only for short durations,” he says. “We were unable to work on our plans.” He says ropeways are still on the list of his party’s priority projects.

Tulsi Gautam, spokesperson for the Ministry of Physical Infrastructure and Transport, says the ministry is well aware of the ropeway’s potential in Nepal, and its suitability in terms of both cost and practicality. “However the government as of now has no plans to commission a ropeway project on its own.” He says it is normal for a ropeway company to get approval from many government agencies. “Even the process of obtaining a citizenship requires several approvals and recommendations,” he adds, making the case for the rigmarole of ropeway project approval.  Manakamana cable car was the first of its kind in Nepal. Manakamana Temple and nearby villages, situated at the top of a hill in Gorkha district, were an isolated place until 1998. People had to walk for almost six hours from Aabukhaireni to reach the top. But things changed drastically after Manakamana Darshan Pvt Ltd started the cable car operation. It transformed the Manakamana area by pulling in over a million tourists a year.

Manakamana cable car was the first of its kind in Nepal. Manakamana Temple and nearby villages, situated at the top of a hill in Gorkha district, were an isolated place until 1998. People had to walk for almost six hours from Aabukhaireni to reach the top. But things changed drastically after Manakamana Darshan Pvt Ltd started the cable car operation. It transformed the Manakamana area by pulling in over a million tourists a year.

Businesses around the area flourished and many new jobs were created. “The benefits of the cable car system were not limited to people living in Manakamana area, but also touched the locals of Kurintar, Malekhu, Munglin, and even Naubise,” says Dilli Narayan Kayastha, the company’s managing director. “I have seen hotels nearby shut down when we closed for maintenance.” It took nearly two decades after Manakamana cable car for Nepal to get another ropeway transport service—Chandragiri Hills Pvt Ltd in Kathmandu, to be followed by Kalinchowk Darshan Ltd in Dolakha and Annapurna Cable Car in Kaski. All of them are privately funded projects.

Also read: Nepal’s most iconic ropeways—now abandoned

“Despite the hurdles, over two dozen cable car services are either in the process of commercial operation, construction or feasibility study,” says Dhakal of Ropeway Nepal.

IME Group, which built Chandragiri Cable Car under Chandragiri Hills Pvt. Ltd., is currently working on five additional cable car services. These include Gaidakot-Maulakalika (1.2km), Butwal Bazar-Basantapur (3km), Chisapani Highway-Rajkada (Kailali), Sikles-Kori (Kaski) and Ghantikhola-Swargadwari Temple in Pyuthan district.

Works are also afoot to start a cable car service in Pathivara Temple in Taplejung. Besides, private companies are conducting ropeway transport feasibility studies in Dakshinkali-Chaukhatdevi, Budhanilkantha-Shivapuri Hill and Bohoratar-Nagarjun Hill in Kathmandu; Godawari-Phulchowki Hill in Lalitpur; Ghorahi-Swargadwari Temple in Pyuthan; Ghyangphedi-Gosainkunda in Rasuwa; Lukla-Namche Bazar in Solukhumbu; Devghat-Moulakalika Temple in Chitwan; and Ranital-Maulakalika in Nawalparasi. Nepal Investment Board is also facilitating the study for an 84-km cable car service from Birethanti-Kagbeni-Ranipauwa to Muktinath Temple in Mustang. If implemented, the project is expected to significantly boost tourism and improve the livelihood of local people.

Dhakal says though cable cars conjure up an image of a major pilgrimage site or tourist destination somewhere in a hill or mountain terrain, they could also help address the problem of traffic congestion in city areas. “Our politicians have been pitching for metro-rail and monorail to ease Kathmandu valley’s traffic congestion,” he adds. “But I believe that the cable car system could better address the problem of urban mobility.” Ganesh Ram Sinkemana, an expert on gravity goods ropeways, has installed ropeways in various parts of Nepal, India, and Bhutan. He says gravity ropeways are perfect for transporting goods as they do not need external power to operate. “Two linked trolleys, on pulleys, run on separate wires suspended from towers. As the full trolley comes down, pulled by the weight of its load, it pulls the empty one up, ready for the next load,” says Sinkemana.

Unlike ropeways for transporting people, gravity goods ropeways do not require many approvals. Just the permit of the respective local government will do. Sinkemana firmly believes that ropeway technology will maximize the use of locally available resources and manpower, creating jobs and business opportunities. “Yet we are not building them. Our politicians are more interested in having expensive roads and bridges.”

When Kushma-Balewa Mechanical Bridge, a ropeway system, was constructed in 2013 to connect two hills of Kushma and Parbat separated by the Kaligandaki River, the four-hour journey between the two places was reduced to four minutes. Local businesspersons initiated the project after the government ignored their request to install a suspension bridge to ease the mobility of goods and people.

“The government did not help us. So we took it upon ourselves and built this ropeway,” says Hom Narayan Shrestha, chairperson of Kushma Balewa Mechanical Bridge Company. Much like Kushma-Balewa Mechanical Bridge, Kotre-Punitar Mechanical Bridge was also built without government assistance in order to connect Tanahu and Kaski.

But it was shut down following the installation of a suspension bridge. Ram Chandra Khanal, chairperson of Kotre Punitar Mechanical Bridge Company, says ropeway transport had to be shut even though many locals favored it over the suspension bridge. “If the government had supported us, we would have revived this technology as the locals are also in favor of Yantrik Pul instead of suspension bridge,” says Khanal.

Dr Baburam Marasini: Discarded tires chiefly to blame for dengue

Health officials have reported a dengue outbreak in Kathmandu and other parts of the country. According to the Epidemiology and Disease Control Division (EDCD), 70 districts across the country have reported a rise in the disease-incidence. Between January and July, there have been over 1,100 known dengue cases. Pratik Ghimire of ApEx talks to Dr Baburam Marasini, public health expert and former EDCD director.

Can you briefly explain dengue’s history in Nepal?

Nepal saw a massive outbreak of malaria in 1958. To fight the disease, a program was launched to eradicate malaria with the assistance of the US. The situation had become largely normal by the 2000s but soon after the program was discontinued, the number of mosquito-borne diseases started to increase again. The first case of dengue in Nepal was reported in 2004 and since, we have been seeing the disease every year, particularly in the Tarai districts. In 2010, over 900 dengue cases and five deaths were reported, in what was Nepal’s first dengue epidemic. Dengue was classified as an epidemic in 2016, 2017, 2018 and 2019 as well, with the disease stalking more than 60 districts.

Dengue used to be common only in the Tarai. But lately, cases have been seen in Kathmandu and other hill regions. What is that the case?

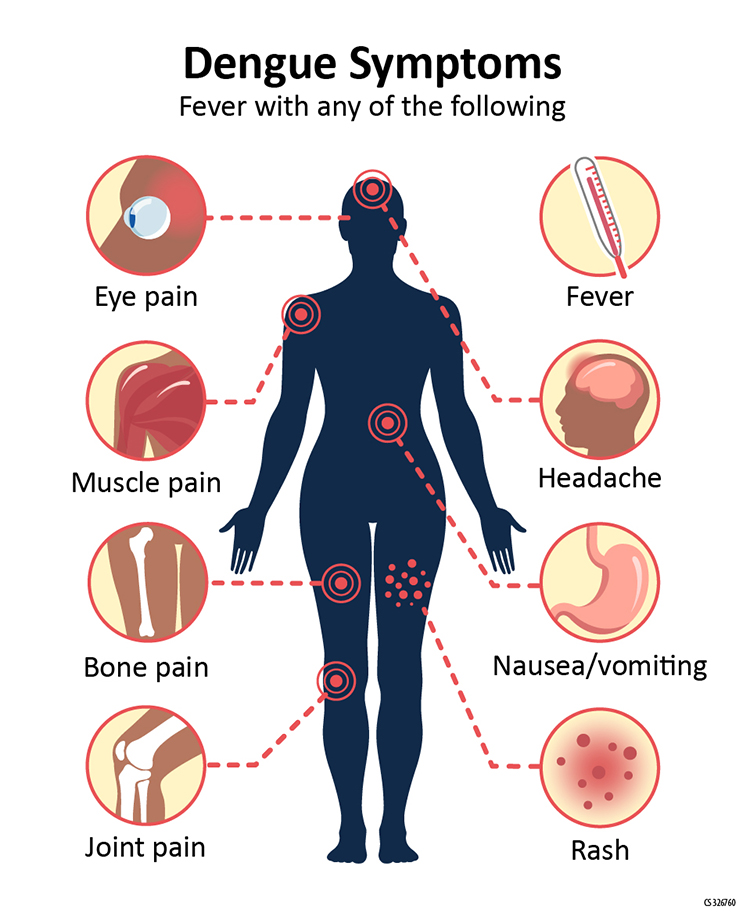

Kathmandu’s weather was not suitable for the mosquitoes carrying dengue virus until a couple of years ago. But in recent years, Kathmandu has witnessed a rise in temperature. As a result, the mosquito species (Aedes aegypti) known to spread dengue and malaria started migrating to Kathmandu and other hill districts. Climate change has contributed to this situation. An infected mosquito lays 500 to 1,000 infected eggs in its lifespan of around 30 days and has a coverage area of 500 meters. So, it won’t take long for infection to spread.

What can we do to protect ourselves against dengue?

The most important thing is not to let mosquitoes breed in our surroundings. Mosquitoes breed in stagnant water, so people should maintain clean surroundings. Discarded tires are chiefly to blame for spreading dengue. They are ideal breeding grounds for dengue-causing mosquitoes. They should be properly disposed. The water in the air conditioner should also be regularly changed, so that the mosquitoes cannot breed there. It is also important to regularly clean our bathrooms and areas where water accumulates. Installing wire mesh on doors and windows, wearing full-sleeve clothes and using mosquito repellent lotion are also effective solutions.

Can there be policy-level interventions to eradicate dengue?

There must be strict laws. First, the government must regulate the way discarded tires are managed. They must be packed in plastic and should not contain water inside. For mosquitoes, tires are the best place to breed as the rubber does not absorb collected water. Lots of tires were burned during protests in Tarai over the new constitution in 2015. This led to a significant decline in mosquito-borne diseases in the region around that time. So you can see how discarded tires can spread dengue and malaria. Covering open drains and sewage systems is also important. Local governments must maintain them for the sake of public health.

The local governments have used fogging to fight dengue. Is that a good way out?

No. Fogging only kills mosquitoes, it does not eradicate them. Our program must focus on destroying mosquito larvae. Besides, fogging also kills other insects like honey bees and butterflies. It is in fact harmful to public health as well. Authorities are launching mosquito-fogging drives just to show that they are doing something to prevent mosquito-borne diseases. They should stop this publicity stunt and do some real work.