Renu Adhikari: Cases of domestic violence against women never decrease

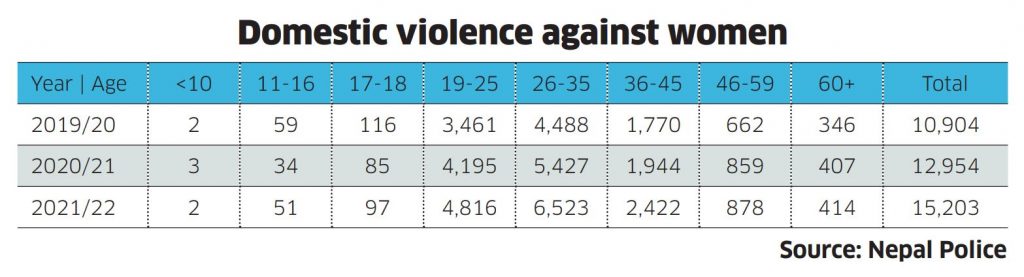

Nepal Police recorded 13,716 cases of domestic violence against women in the fiscal year 2018/19. This figure dropped to 10,727 in 2019/20 before rising again to 12,832 in 2020/21. Many women rights organizations, including Women’s Rehabilitation Center Nepal (WOREC), believe the cases of domestic violence were grossly underreported during Covid-19 pandemic. Pratik Ghimire of ApEx talks to Renu Adhikari, chairperson of WOREC.

Why do you think cases of domestic violence increased during the pandemic?

The main reason is that everyone was cooped up in their homes for a long time. In households with a history of domestic violence and abuse, women were not safe. They might have been abused and beaten by their husbands and partners but the reporting mechanism was weak during the lockdown. As a result, cases of violence against women were underreported.

Did the cases decrease after the easing of the lockdown then?

Cases of domestic violence against women never decrease. Certainly, the reported case numbers fluctuate from one month to another, but that does not mean the incidents of domestic abuse and violence are going down. You can see this if you refer to WOREC’s monthly report. What we can deduce though is that cases drop during the festive holidays as the survivors do not report them. It was the same during the lockdown.

Are our legal laws adequate to come to the help of domestic violence survivors?

They are. If you look at provisions for cases related to domestic violence (excluding sexual violence and others), they are progressive. Besides punishment to the abuser, our laws include the provisions of compensation, a safe house and counseling for the survivors. But what we lack is implementation. Those who are in charge of providing justice are simply unaware about these provisions. The way Nepali society treats its women is not helpful either. Our society further inflicts emotional and mental torture on the survivors. Take the recent case of Niharika Rajput, which again shows the general mindset of Nepali society towards a survivor of violence. Many people still don’t acknowledge the rights and identity of women.

How would you rate the life of survivors who have reached out to your organization?

If the survivors return to their abuser’s house, it is only a matter of time before they are abused and mistreated again. WOREC has come across many cases where survivors have come back to our organization seeking safety, as their decision to return to their abusers didn’t go as expected. But those who started living alone or with relatives are doing well. They are working to sustain their life and living independently.

What problems do those survivors living in shelter homes face?

I can’t tell you about other shelter homes but only our own. Teen pregnancy is a serious concern for us. There are child rape survivors who become pregnant. Their belly do not start showing until the sixth month and by that time they are past the abortion cutoff period. I have been raising this concern with the authorities, to no avail. While adult survivors can live independently after support and counseling, the same is not the case for young girls and teenagers. The authorities should come up with a plan to address this issue.

Hotline numbers

Nepal Government: 1234

Armed Police Force: 1114

Nepal Police: 100, 1113 (for rescue)

Ministry of Women, Children and Social Welfare: 1618014200082

National Women Commission: 1145

Transcultural Psychosocial Organization Nepal: 16600102005

WOREC: 16600178910

Shakti Samuha: 16600111117

Baibhav Paudel: Expanding the family business

Barahi Hospitality & Leisure has been serving customers for almost four decades now. The business that started out with an ordinary lodge in Pokhara has today expanded into a group of four-star hotels and restaurants. Pratik Ghimire of ApEx talks to Baibhav Paudel, the company director.

What attracted you to the hospitality business?

As Barahi is a business started by my father, I got to know about this sector from an early age. Also, I grew up in Pokhara’s Lakeside area, where my childhood was spent around tourists. I guess, that experience also drove me towards hospitality and tourism. I went to the US for my higher studies at 17. There, I learned more about hospitality and tourism. I did my master’s degree in International Business and I am currently doing my MBA in Tourism and Hospitality. Despite being a Green Card holder in America, my interest in this sector brought me back to Nepal to join my family business. Besides being the director of Barahi Hospitality & Leisure. I am also a board member of the Hotel Association as well as Restaurant Association Nepal. I am also serving as the president of Gandaki Toastmasters and have completed my tenure as the president of the Nepalese Young Entrepreneurs Forum. So I am closely tied to the hospitality and tourism industry of Nepal.

Tell us about your pandemic experience.

The tourism and hospitality sector was the first one to get hit and the last one to recover from the Covid-19 pandemic. Many businesses had to shut down. But we used the period focusing on renovation works of our hotels. We renovated all of our amenities, something we had been planning to do for a long time. We utilized the period perfectly.

What are the hotels that fall under Barahi Hospitality?

There are three in total. Hotel Barahi in Pokhara and Barahi Jungle Lodge in Chitwan are four-star properties. The other one is Sarangkot Mountain Lodge. Besides that, I have my startups too: Bobs Gym, Byanjan Restaurant, Bagaincha Wellness Resort and The Beach Bar and Lodge.

How is Barahi Hospitality & Leisure different from others?

We have a legacy that others don’t. In our 40 years of service, we have made ourselves a trusted brand. We also routinely upgrade and maintain our properties. Every five years, we do regular maintenance and renovations. We keep trying new designs and amenities in our hotels to satisfy our customers’ needs.

What changes did your leadership bring to the business?

I have focused on expanding our branches. Next month, we are planning to open Barahi Plaza in Kathmandu. In Pokhara, a new project, Barahi Sedi, is under construction and two more projects, Bastup Resort in Pokhara and Barahi Bodhi in Lumbini, are in the designing phase.

What is your advice to aspiring entrepreneurs?

I suggest them not to rush. Quite often, I have seen young entrepreneurs expecting profit right after the investment, but the business doesn’t work like that. You have to wait for years. Many aspiring entrepreneurs were skeptical about investing due to the pandemic but as things have eased now, I hope they will enter into business.

Remembering Pradip Giri: Towering intellectual with a young heart

Birth: 10 Oct 1947, Siraha

Death: 20 Aug 2022, Lalitpur

I met Pradip Giri in person in early 2020, at a protest against the government decision to slap 10 percent customs duty on imported books. We were holding a petition-signing event and had invited students, readers and scholars who considered books an important part of their lives. He was among the handful of prominent figures to show up at the program organized by a loose group of students. Very few youth political leaders were in attendance. But Giri, a Nepali Congress veteran widely hailed as a socialist thinker, was there.

To say we were honored by his presence would be an understatement. The intellectual leader was forthright and funny. Finding himself in the midst of smartphone-wielding, selfie-taking youths, he asked, with a smile on face, if we were organizing the event just as a social media stunt. He also wanted to know about our favorite books and authors.

Giri peppered us with questions about books and literature that day, and we tried, as best we could, to satisfy his curiosity. After listening to us, he suggested what books and authors we should read. He seemed pleased that the reading culture had not died in Nepal, and that the youths—not the scholars, writers, or civil society members—were leading the protest against the book tax.

When we informed Giri that the police had detained us twice for protesting. He advised us to keep protesting, no matter what. “To safeguard democracy, you have to keep up pressure on those in power,” he told us. “Your bottom line should be the fulfillment of your demand—don’t settle for anything less.” We were a fairly small group standing up against the powers that be. His vote of confidence gave us courage to persevere.

“Democracy is not just about the majority. Each voice must be heard,” Giri used to say on the parliament floor and at public gatherings. He championed the cause of minorities—and why he had decided to show up at our protest that day. He wanted competent young people to lead the country, and so he would visit youth-led campaigns to motivate them.

Within his own party, he was in favor of young leaders taking leadership. This made him an outlier among his party peers. Yes, Giri was a Congress leader but he always stood for the right cause, even if it meant going against his own party. A strong advocate of socialism, Giri was a strong supporter of non-violence, yet in his view, the decade-long Maosit movement was the base of ensuring the rights of Madhesis, Dalits and women.

When Nepal promulgated the new constitution in 2015, he defied the party whip and refused to endorse the charter, arguing that it did not address the concerns of Madhesi people. Nepali Congress did not punish him for the disobedience.

Born into a political family in Siraha district, Giri was introduced to politics in his late teens. He went to Jawaharlal Nehru University in India, where he made many friends who went on to become top politicians. He himself eschewed executive roles throughout his political career, for which he was applauded by one and all in Nepal, a country that has had more than enough power-hungry politicians.

During his student years in India, he was highly influenced by the socialist movement of Jayprakash Narayan and Ram Manohar Lohia. Giri was a highly learned man, whose interests ranged from politics to theology to philosophy. He was a politician, a public intellect, a thinker and a champion of the downtrodden. We are all poorer for his death.

ApEx Series: Doing ropeways again

Ropeways can be a vital means of goods-transport in a country like Nepal with its rugged terrains and ever-present risks of roads being blocked by water-induced disasters. Compared to air and road transport, ropeway transport is cheaper too.

The importance of ropeways for Nepal had become evident even a century ago: construction on the country’s first ropeway, the 22-km link between Makawanpur and Kathmandu, had started in 1922 under the orders of Prime Minister Chandra Shamsher. In the latter half of the 20th century, the country had many more ropeway lines.

In 1986, Hetauda Cement Factory started one to ferry limestones. In 1995, the Conservation Ropeway was built at Bhattedanda on the outskirts of Kathmandu valley to transport milk. There were a few other lines as well. But they soon fell into disuse as the national focus shifted to road-building, despite clear evidence of the cost-effectiveness of the ropeways.

Now the discourse on the revival of ropeways in Nepal has again started. We explore the various dimensions of this debate in this five-part, bi-weekly ApEx series.

Part I: Nepal’s most iconic ropeways—now abandoned

Part II: High in potential, low in execution

Part III: Is ropeway revival possible?

Part IV: International ropeway practices and lessons for Nepal

ApEx Series: Nepal’s most iconic ropeways—now abandoned

The year 2022 marks the centenary of the start of ropeway transport in Nepal. It all began with a 22-km cargo ropeway between Makwanpur to Kathmandu. Construction on it started in 1922 and was completed in 1927. A separate four-km Swayambhunath Ropeway was built in 1924 to ferry stones from a quarry in Halchowk all the way to Lainchaur in order to build Rana palaces and roads. These pioneering and other ropeway projects have either disappeared or are no longer in operation. Here we discuss some such ropeways that once played a vital role in transport of goods and as a vehicle for the country’s economic development.

Tri Chandra Nepal Tara Ropeway

If you have traveled from Kathmandu to Hetauda via Mugling, you might have noticed rusted carriages attached to a cable over the Trisuli River. This ropeway, now abandoned, was among the first of its kind in South Asia. It was commissioned by the then Nepali Prime Minister, Chandra Shamsher, in 1922. The British government had funded the project as a gift to Nepal for its support in the First World War.

The 22-km-long Tri Chandra Nepal Tara Ropeway came into operation in 1927 and it is believed to be one of the first ropeways in the whole of South Asia. It linked the villages of Matatirtha in Kathmandu with Dhorsing in Makawanpur. It was used to transport goods that were brought via Raxaul in India. The consignments were transported from Amlekhgunj in Bara up to Dhorsing in trucks and dispatched to Matatirtha in Kathmandu on the ropeway. A single carriage, traveling at 6.8 km an hour, could bear 254 kg.

In 1964, the ropeway was extended and upgraded with American assistance to transport goods from Hetauda to Kathmandu, as the Tribhuvan Highway used to be frequently obstructed due to landslides. The ropeway was 42-km long and had a hauling capacity of 22 tons an hour. It started falling out of favor in the early 1970s, says Guna Raj Dhakal, chairman of Ropeway Nepal Pvt. Ltd., mainly due to poor planning, mismanagement and political meddling. “Political interference led to overstaffing and at the same time, paucity of technical staff. The infrastructure also could not be maintained as and when necessary,” says Dhakal.

The country’s first and one-of-its-kind ropeway went out of commission following a technical glitch at one of its substations in 1999. The problem could have been fixed for as little as Rs 400,000 but the government of the day chose not to. Tri Chandra Nepal Tara Ropeway, which could transport goods from Hetauda to Kathmandu in four hours, at the cost of 34 paisa a kg, was permanently shut in 2001. At the time of its closure, it used to operate 10 hours a day and employed almost 900 people.

Hetauda Cement Factory Ropeway

Hetauda Cement, established in 1976, was one of the most successful factories in Nepal, thanks largely to the ropeway system. Starting in 1986, the state-owned factory used the ropeway to transport limestone from a quarry located 11 km away. It could transport 150 tons of limestone in an hour.

Moreover, the cost of ropeway transport was almost half compared to truck-use. The factory thus saved around Rs 2m a year in limestone transport alone. It had no major operational problems other than some technical issues as a result of wear and tear and lack of regular maintenance. The ropeway operated for nearly 17 years before it was abandoned—again, over a fixable issue. According to the book ‘Ropeways in Nepal’, the ropeway was discontinued after one of the frames propping the cable system sank following a landslide. It was permanently shut in 2004.

Meanwhile, the Hetauda Cement Factory, though still in operation, is fast-turning into a white elephant. Factory officials plan to sell the rusted ropeway equipment, which pose risk to the settlements below, but no buyers have come forward.

Bhattedanda Milkway

During the 1990s, villagers of the erstwhile Ikudol Village Development Committee in Lalitpur district mostly relied on buffalo farming. But their products including milk lacked market access, as the nearest collection center was at Tinpane, a five-hour walk away. Milk would curdle up by the time villagers reached the center. So they turned the milk into ‘Khuwa’ (a thickened dairy product made by heating up milk), and sold it at Chapagaun, a 10-hour walk away from Ikudol. The process of making Khuwa was labor-intensive and polluting as the villagers burned firewood to boil the milk. So Bagmati Watershed Project (BWP) considered stretching a steel cable across the valley and using it to transport fresh milk in a much shorter time.

In 1995, Conservation Ropeway was built at Bhattedanda to transport milk and clean up the dirty Khuwa business. Every day, 143 households in Ikudol used the ‘milkway’ to collectively sell around 900 liters of fresh milk a day. “Besides milk, the ropeway also benefited vegetable and flower farmers,” says Madhukar Upadhya, a team member of BWP. “The others who profited were merchants, construction contractors, local cooperatives, and development workers who used it occasionally to transport goods”. But traffic on the milkway started declining after 1996. A road to Chhabeli opened up and people could now transport their goods on vehicles.

Still, the Bhattedanda ropeway was in profit and a plan to extend its span was afoot. But the plan never reached its fruition as the local villagers felt that they could do without it. The milkway stopped operating in 2001 after helping the rural economy for more than five years. “Lack of local support plus the new road connectivity doomed it,” says Upadhya. The ropeway was briefly revived when landslides damaged the roadway in the Bhattedanda area in 2002 but was permanently shut down in 2004 following road repairs.

Barpak Community Ropeway

When Bir Bahadur Ghale, a local of Barpak village in Gorkha, went to Hong Kong in 1986, he was fascinated by the cable cars he saw there. He saw them as a convenient way of transporting goods and people in hill areas. He returned home with the dream of building a ropeway in his village. His dream would come true in 1998 when the British Embassy in Kathmandu in cooperation with the Intermediate Technology Development Group (ITDG-Nepal) agreed to help with a goods-carrying ropeway in Barpak.

The ropeway connected Rangrung and Barpak—villages separated by a two-day hike—and had an immediate impact on the people and the local economy. Every day, three tons of goods were transported to Barpak. The ropeway made an average of 20 trips a day between 10 am to 5 pm, and generated an average daily gross income of Rs 1,500. Writing in ‘Ropeways in Nepal’, Ghale mentions that the selling price of transported goods had dropped by Rs 2-3 a kg (and even more) after the ropeway came into operation. For instance, the cost of a four-kg sand-pack went from Rs 8 to Rs 3. The neighboring villages of Laprak and Gumda also benefited from the ropeway.

However, the ropeway was shut down just four months into its operation in May 1999 following an accident when four people riding in the goods carriage died when the hauling cable snapped. Ghale says the ropeway was not meant for transporting passengers but the villagers did not listen. They argued that they too should be allowed to travel via the ropeway as the technical staff did the same for maintenance purposes. The ropeway, which instantly became a profitable enterprise, was permanently discontinued following the fatal accident.

Gopaldas Bade obituary: A Gandhian to the core

Birth: 29 May 1924, Kavre

Death: 3 August 2022, Kavre

Gopaldas Bade, a Nepali Congress leader who championed the Gandhian philosophy of truth, non-violence and service to humanity all his life, passed away on August 3. He was 98.

The last of the surviving first-generation Congress leaders from Kavre district, Bade was born into a well-to-do family and had a relatively comfortable childhood. His priority was never money. He instead believed in living a simple life and serving people.

At a young age of 17, Bade traveled to India to become a resident of Gandhi’s ashram in Gujarat, where he stayed for six months. Tulsi Mehar Shrestha, a close aide to Gandhi, was a friend of Bade’s elder brother Rajdas. It was through this connection that Bade became one of the few Nepalis to learn about politics, philosophy and ways of living under the Mahatma himself.

Bade regarded his time at Gandhi’s ashram as “a divine grace” and would champion Gandhi’s ideology all his life. At the ashram, he also met prominent Indian scholars, politicians and reformers including Madan Mohan Malaviya, Vinoba Bhave and Kaka Kalelkar. The influence of these individuals also shaped Bade’s political and social thoughts.

After returning to Nepal, Bade became active in politics alongside his brother. It was the time of absolute Rana rule when party politics and democratic movements were being squelched.

Bade began attending the clandestine meetings of Nepali Congress both in Nepal and India. In this period, he also built close relations with the party’s top leaders including BP Koirala and Krishna Prasad Bhattarai. Once, he even hosted the leaders, both wanted by the authorities at the time, in his Kavre home before escorting them safely to Kathmandu in a secret political mission.

“Bade’s home in Kavre used to be a safe house and the party’s office,” says Ramhari Khatiwada, a Congress leader.

After Rajdas died young in a plane crash, Bade took it upon himself to realize his elder brother’s dream of becoming a freedom fighter, for which the Ganeshman Singh Foundation honored him with the title of ‘Prajatantra Senani’ in 2020.

Though Bade remained active in politics most of his life, he always considered social service his priority. (He was a Gandhian after all.)

He was involved in many charity and social works in his district, mainly his hometown Banepa and is credited with laying the town’s modern foundation.

He is survived by two sons and daughters each.

Santosh Sapkota: Finding happiness in an unexpected opportunity

We all have had a moment when we were uncertain about what our future career will look like. Some of us stick to the profession we are in, whereas some of us take a slightly different path. But for Santosh Sapkota, it was not just a slight adjustment but a total change of career path.

Sapkota, now 24, has been working as a social media manager for several well-known faces in Nepal and India. But his initial interest was completely opposite to what he was doing now; digital entrepreneurship.

Born in Parbat, Sapkota was moved to his aunt’s house in Rupandehi at the age of three to ensure his better schooling. “At that time, Maoists were bombing every private school in my village. For safety and education, I was sent to Rupandehi,” he tells me.

He completed his schooling and moved to Bangalore, India to receive a diploma in mechanical engineering in 2013. Little did he know that his career would totally change.

Completing the diploma in 2015, Sapkota worked for 2 years in Bangalore as a service supervisor in Sri Manjunatha Pipes and returned to Nepal in 2018. In Nepal, he got his hands on a job as a service advisor in one of the companies of Agni Group, namely Agni Motoinc Pvt. Ltd.

But things took a different route in 2017, when he became an admin of the Facebook fan page for Arujn Sapkota, his cousin who had started his journey as a Nepali folk singer. He was unable to complete his engineering studies due to some family and financial issues. Nevertheless, he had not lost his hope.

Although unable to fulfill his initial goals, Sapkota, a folk song lover and cricket enthusiast, was adapting to his new role as a social media manager. But that journey wasn’t easy for him either. “I faced a lot of issues within the fan page, with no clue on how to solve it,” he says. Slowly but surely, he did get a handle on those issues, and the page started getting responses. He started getting better at what he was doing, which was clearly seen on the page he was handling. “The fan page started getting more of an audience, because of which my brother started getting a lot of inquiries on who was handling the page,” he tells me.

His exposure grew when people started finding out that he was behind the management of the fan page, and various celebrities started offering him jobs to handle their social media. Celebrities faced a lot of issues, like accounts and pages getting hacked, and some were facing problems while publishing their posts, for which they started seeking Sapkota’s help.

“I think it was the realization that well-known people were looking for my help, that boosted my motivation to take this work as a career,” says Sapkota.

It was only in 2019 that Sapkota started collaborating with other celebrities and handling their social media. One major attraction for him in this job was the way the pages worked. “It excites me to see followers increase, to communicate with many people, and most of all, being able to convey messages to a large group of audiences,” he tells me.

Although quite interesting, he says that the task is difficult, especially in Nepal. “Here, it is difficult to make payments to boost the posts, properly monetize the accounts, and also Nepal is not eligible for page monetization,” he says. Along with that, the job does not have any working hours. Sapkota needs to be available at any time of the day, as there is no surety on when his clients might need him to solve a problem in their account. “Accounts might get hacked at 1 am. We never know,” he says. And sometimes, it might take hours to solve such problems, giving him no guarantee of how much time he will have to invest.

Currently, Sapkota handles 15 social medias in total, of six celebrities, among which some of them are Saigrace Pokharel (Nepali storyteller), Kushal Bhurtel (Nepali cricketer), and Shirish Devkota (Nepali singer). In the past, he has managed social handles of known personalities like Maheshwar Jung Gahatraj (Sports Minister of Nepal), and Mujahid Alam (an Indian politician).

He believes that there are a lot of opportunities for youths in the digital world. “There are a lot of areas to explore in digital and social media, you just have to find the right path for yourself,” he says.

In the case of Sapkota, he does not see himself leaving this job anytime soon. “I love what I do. As long as people face problems with social media, you will definitely see me around trying to solve those problems,” he says with a satisfaction in his voice.

InDepth: Will there be demand for Nepal’s excess electricity?

Sixty-four percent of Nepal’s industries are compelled to install diesel generators in light of the frequent power outages, according to a research paper by the Confederation of Nepalese Industries (CNI) published in May 2022. Generator-use, the paper says, increases the industries’ monthly operation costs by an average of 5.3 percent.

Nepal currently exports 364MW surplus electricity a year to India but it cannot meet its own domestic energy needs.

Suresh Bahadur Bhattarai, spokesperson for the Nepal Electricity Authority (NEA), the country’s primary energy producer and sole transistor and distributor, disagrees with the CNI report.

“Yes, there are power outages in industrial areas but I doubt 64 percent of Nepali industries have to rely heavily on generators,” he says. “The fact is, new industries are facing shortages due to the lack of transmission lines.”

The 2017 Electricity Demand Forecast Report by the Water and Energy Commission Secretariat, under the Ministry of Energy, projected the country’s electricity demand to shoot to 5,800MW by 2025 and to 9,000MW by 2030. These projections were based on the predicted long-term GDP growth rates, as forecast by the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

But the government’s projections do not add up. According to the report, the demand should have reached 2,500MW by now. But Nepal’s current electricity demand stands at around 1,800MW in peak hours (mornings and evenings) on working days and around 1,100MW in base hours (daytime). Likewise, the demand drops to 700MW in off-hours (11 pm-5 am).

Also read: A snapshot of Nepal’s energy ecosystem

Nepal’s most power-dependent sectors are manufacturing, followed by households, service industry and transport.

The government also predicts an average 10 percent increase in annual electricity demand, which is also not in keeping with the reality.

Energy experts say national economic growth and energy consumption are directly proportional. In other words, energy demand will increase only if the GDP growth rate also goes up.

Nepali industries have asked for a yearly average of 400MW in bulk electricity to meet their needs, which the NEA has been unable to supply, says the CNI.

Bhattarai, the NEA spokesperson, maintains that building more transmission lines is the answer.

“A few transmission lines are in the pipeline. When they are ready, a lot of the supply-demand discrepancies should be resolved,” he says.

According to him, the NEA is currently conducting feasibility studies for the 90-km Lamahi-Chhinchu, 130-km Sitalpati-Inaruwa, and 115-km Arun Hub-Dudhkoshi transmission lines. The carrying capacity of these lines is 4,400MW.

“Slowing down progress on these lines are the various political, environmental, and financial hurdles,” adds Bhattarai.

Mukesh Kafle, former managing director of the NEA, blames the current leadership at the authority for the failure to meet the industries’ demands.

“During my tenure, I treated the whole country as a single house. There was uniform load-shedding as a result,” he says. “The current leadership at the authority, however, has ignored the industries in order to meet household energy needs.”

Kafle claims Nepal is producing enough electricity for everyone.

But over the years the nature of the challenge in electricity demand and supply has changed.

“We are in a situation whereby we need to increase the demand now. We are on the verge of an electricity demand-deficit,” Kafle adds. “Even if the electricity authority meets the current demand of the industries, we will still have a surplus.”

This year alone, the government has signed power purchase agreements on 7,000MW with different private producers. In the next couple of years, this will be added to the national grid even without a corresponding increase in demand.

Shailesh Mishra, CEO of Independent Power Producers Association, shares Kafle’s view.

“I also don’t see any problem with electricity production,” he says. “But despite our comparably low demand, we are still unable to adequately power-up our industries due to our poor distribution lines.”

The latest budget for the fiscal year 2022/23 aims for a median GDP growth rate of around seven percent. In that case, the electricity demand is expected to see a 14 percent and a 28 percent bump by 2025 and 2030 respectively.

Nepal can produce around 42,000MW of electricity. If the country grows at around nine percent a year, it will be in a place to utilize its maximum capacity by 2040.

Also read: Is our energy ecosystem consumer-friendly?

The electricity sector has at least conducted some studies and formulated relevant plans and policies. Not so with petroleum. The Nepal Oil Corporation (NOC), the country’s sole importer and distributor of petro products, has undertaken no such long-term studies.

“In keeping with previous trends, the NOC assumes that the demand for diesel, petrol, and aviation fuel would all increase by around 10 percent a year, while the LGP demand would go up by 20 percent a year,” says Binit Mani Upadhyay, the spokesperson of the corporation. “As we import based on current demands, there have been no other assessments.”

In the fiscal year 2020-21, the NOC sold 587,677kl petrol, 1,698,427kl diesel, 70,400kl aviation fuel, and 477,752MT LPG. (The expected import figures for 2025 and 2030 are listed in the table alongside.)

A 2017 Asian Development Bank report ‘Nepal Energy Sector Assessment, Strategy and Road Map’ forecast a 1.9 percent annual increase in the country’s energy demand through 2035. This was slower than the projected GDP growth rate of 3.7 percent for the same period.

Likewise, the share of electricity in the energy demand of the industry sector would increase from 25 percent in 2010 to 35 percent by 2035, or by 5.4 percent a year. At the same time, the share of oil and coal will increase by 4.3 percent and 3.7 percent, respectively.