Bhairab Risal: A scribe on a green mission

Quick facts

Born on 12 August 1928 in Bhaktapur

Went to Ranipokhari Sanskrit Pathshala, Kathmandu

Graduated from Nandi Ratri Pathsala, Kathmandu affiliated to Banaras Sanskrit University, India

Started working for Halkhabar in 1956 becoming the pioneer in environmental journalism

Husband of Sushila Risal

Father to Gokul Risal, Bhaswot Risal, Sushma Risal and Susham Risal

My father was a Hindu priest and he wanted me to follow in his footsteps. I was sent to a Sanskrit school and even in my school days, I used to be a part-time priest, performing various rituals.

I grew up during the Rana regime when the ruling class was cruel to the citizens. They were aware of this and as a way to wash away their sins, they used to send Brahmin children like me to school. The school was free of cost and so was the hostel where I got my education along with other Brahmin boys.

I graduated in 1955 but didn’t get a job because of my involvement in the communist movement. I needed to work in order to take care of my family. So I took a job as a reporter at Halkhabar, a daily newspaper, in 1956. That was how I started my journalism career, not out of passion but of desperation.

I used to cycle around Kathmandu Valley to collect news and report on everyday issues concerning the people at the grassroots. My monthly salary was Rs 100.

Political reporting was not easy at the time. People were poorly informed about press freedom or right to information and they were less interested in politics.

I was popular among the readers as I used to report on new issues every day, from Kathmandu and also other parts of the country.

I used to regularly see Bedananda Jha, Dilli Raman Regmi, and BP Koirala. These visits were important for my career as a journalist.

I had a beautiful relationship with these three political leaders. I visited them for news and they were more than happy to oblige as I was covering the issues that concerned them.

I had an extensive source of news, and I used to be privy to government secrets. For example, I knew that death penalty was legal back then, but the government had kept it a secret from the general public and the world.

My method of journalism, if you can call it that, is to roam around and meet people to find if there are worthy news stories.

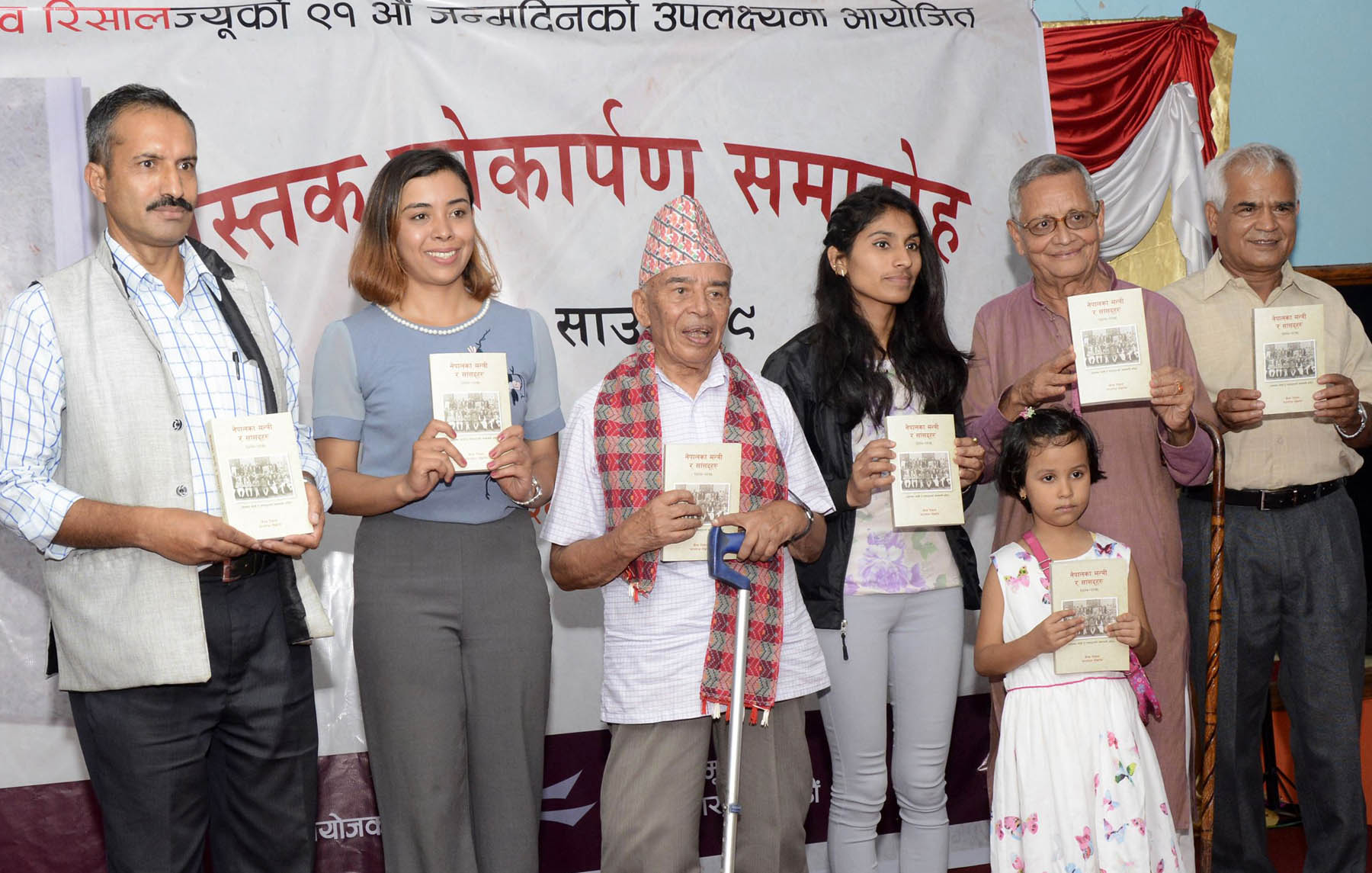

Bhairab Risal (third from left) releasing his book Nepalka Mantri Ra Samsadharu on the occasion of his 91st birthday in 2020 | RSS

Bhairab Risal (third from left) releasing his book Nepalka Mantri Ra Samsadharu on the occasion of his 91st birthday in 2020 | RSS

My career as a journalist was halted in 1959 when Halkhabar shut down. I found myself in need of a new job. I then got selected as a temporary officer for a national census. The job allowed me to travel across Nepal, which helped me discover different types of societies, environments, and lifestyles. I led a team that counted the people of Kalapani, Lipulekh, and Limpiyadhura—now disputed territories claimed by both Nepal and India.

After the census, I again tried to get involved in journalism. I had developed a passion for the job during my time at Halkhabar. So I gave an exam for the Rastriya Samachar Samiti (RSS), a government news agency, in 1963. I failed but the person who had passed and was selected quit after a couple of months, and I was hired in his place.

I worked with RSS for over two decades. But things were not as easy as in Halkhabar. At the RSS, we had to follow the government’s instructions, only write about select topics. We were not allowed to criticize the government, at any cost.

Even when there was a shortage of salt, sugar, kerosene, and other daily essentials, we had to write that there was no such shortage.

I never enjoyed being a government spokesperson, and I had several bust-ups with my news chief. I couldn’t be honest to the profession at the RSS. So I eventually quit and decided to make my name as a freelance journalist.

At that time, I also started noticing that the environment in Kathmandu was deteriorating. So me and my colleagues formed a group of journalists to report on and raise awareness on the environment. This group would eventually turn into Nepal Forum of Environmental Journalists (NEFEJ) in 1986, which in 1997 founded Radio Sagarmatha—the first independent community radio in South Asia.

The NEFEJ team also launched the ‘Save the Environment’ movement and held several demonstrations to protect the environment. I have also worked as an activist in the ‘Save Bagmati’ campaign.

Until a few years ago, I used to regularly visit the studio of Radio Sagarmatha to run a program. But these days my health is wobbly and I run the program via telephone. I also write for newspapers sometimes.

I have worked in this field for long and have seen different phases of Nepali journalism. It has definitely evolved but back during the Panchayat days, despite the autocratic political system, the rulers used to read news and listen to what journalists had to say. That is not so these days. Politicians don’t care about the issues that are being written about or broadcast. They feel no responsibility towards the public.

About him

Ninu Chapagain (Colleague)

Despite his age, I still consider him a youth. He is still more dedicated to journalism than many of the young journalists I know. Brought up in a Hindu family, he has made his way from a priest to a full-timer communist to a pioneering environmental journalist. He has always walked on the progressive path.

Tejeshwar Babu Gongah (Friend)

In Nepali, ‘Bhairab’ means sky. And our Bhairab Risal is also like the sky, covering a wide swath of knowledge. I respect him for his contribution to Nepali journalism. His activeness even at this age keeps me inspired, as I am only five years younger than him.

Kosmos Biswokarma (Colleague)

Bhairab Risal is an exemplary figure in Nepali journalism. Even in his 90s, he is active as a freelance journalist. His contribution to environmental journalism is immeasurable. He started environmental journalism in Nepal. He has seen and experienced a lot. A meeting with him is always filled with interesting tales.

A shorter version of this profile was published in the print edition of The Annapurna Express on June 9.

related news

Harry Bhandari: An inspiring tale of Nepali immigrant in the US

Sept. 14, 2023, 4:06 p.m.

Baburam Bhattarai: An analysis on Nepal’s underdevelopment

Sept. 4, 2023, 9:36 a.m.

Shyam Goenka: Institutionalizing free press and democracy

Aug. 29, 2023, 7:42 p.m.

Sunil Babu Pant: A guardian of LGBTIQA+ community

March 11, 2023, 10:01 p.m.

Usha Nepal: An inspiration to every working woman

Feb. 25, 2023, 9:42 p.m.

Anupama Khunjeli: A trailblazer banker

Feb. 19, 2023, 12:54 a.m.

Capt Siddartha Jang Gurung: Aviation rescue specialist

Feb. 12, 2023, 1:26 a.m.

Bhuwan Chand: Born to perform

Feb. 4, 2023, 6:36 p.m.

Comments