National Politics | Can Dahal again revive the Maoist party?

“This is my last opportunity to serve the people and probably my ultimate challenge as well,” said CPN (Maoist Center)’s Pushpa Kamal Dahal soon after being re-elected party chair. In his political document endorsed by the Party's 8th General Convention, Dahal confessed that people these days struggle to differentiate the Maoists from other political parties.

This clearly indicates the mother Maoist party is facing an identity crisis. In the general convention that concluded in the first week of January, the party vowed to take reform measures. But that is a daunting task given the party’s ideological ambiguity, which is only compounded by its dysfunctional organization.

Dahal often claims republicanism, federalism, and secularism are original Maoist agendas that have now become national agendas, and he must get credit for that transition. But those agendas seem increasingly divorced from the Maoist party. “Obviously, the credit for establishing these agendas goes to the party,” says political analyst Sudarshan Khatiwada. But they are no longer exclusive Maoist agendas as other parties have also taken their ownership. When the Maoist party pushed those agendas ahead of the first Constituent Assembly (CA) elections in 2008, the public supported the breath of fresh air. No more.

In order to regain party strength, Dahal is trying to placate Janajati, Madhesi, and other marginalized communities by raising the possibility of constitution amendment. But he has already lost the trust of these constituencies after merging his party with the CPN-UML led by KP Sharma Oli, who fiercely opposed those very agendas. These constituencies no longer consider Dahal their leader. But Vijaya Kanta Karna of the Center for Social Inclusion and Federalism, a think-tank, says there is still a remote possibility of Dahal retaining his strength if he can somehow again win the trust of marginalized communities, his previous source of strength and power. It was when Dahal abandoned progressive agendas, says Karna, that he and his party became weak.

Dahal’s party has been in power in all governments formed after the promulgation of the new constitution in 2015. In 2015, he supported CPN-UML Chairman Oli. Then he broke the ruling alliance with Oli and formed a coalition government with Nepali Congress, becoming prime minister in 2016. In 2018, his party joined another Oli-led government, ultimately merging the Maoist and UML parties. Now, his party is a key coalition partner of Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba. Analysts say this tendency to stick to power is an example of Dahal’s deviation from his ideological core.

The party’s revival demands a clear ideological positioning, says analyst Khatiwada, but Dahal is these days characterized by ideological confusion and ambiguity. “Dahal has talked about embracing socialism with Nepali characteristics but he is short on details,” adds Khatiwada. “And he cannot draw public support only by committing to socialism”.

Maoist party leaders, however, are hopeful as the party’s CC has been mandated to sketch a plan on how the party commits itself to socialism.

Says newly-elected CC member Hemraj Bhandari, the convention has provided a clear guidance on how to move ahead and details of the roadmap will be finalized through the CC meeting. “We will tell the people that in order to guard secularism, federalism, and inclusion, the Maoist party needs to come back to power,” he says.

Ideological deviation is not the only cause for the Maoist party’s decline. After joining peaceful politics, the party didn’t bother with adapting its war-oriented organization to peaceful politics. Additionally, its organization began to crack after the party faced a vertical split on the issue of peace and constitution. Over the decades the party has suffered multiple splits.

In 2012, a large chunk of party leaders and cadres led by Mohan Baidya left, which significantly eroded the party’s strength. The party was duly relegated to third position in second Constituent Assembly (CA) elections in 2013.

In 2015, Dahal’s ideological backbone Baburam Bhattarai left the party. With the realization that he could not revive the party, Dahal then decided to merge with UML in 2018, completely sidelining ideological issues and party’s core agendas.

Also read: 2021: A year of politicization of democracy

The electoral alliance with UML in 2017 helped the Maoist party maintain a strong presence in national politics. But with the Supreme Court order last year, the Maoist party was revived yet many of its senior leaders and cadres decided to stay with the UML, further weakening the party. Last year, some leaders also proposed the idea of renaming the party, removing the Maoist tag. Maoist leaders such as Devendra Poudel and Phampa Bhusal even proposed a name-change, to which Dahal reacted positively. But then nothing came of it.

In the document presented at the general convention, Dahal has confessed to mistakes which contributed to the party’s erosion. Dahal is perhaps not very hopeful, which is why he says this is his last chance.

Dahal’s document, too, is old wine in a new bottle. For instance, the party aims to engage its cadres on production, an old proposal that never saw light of the day. Similarly, the document talks about maintaining fiscal discipline and transparency and curbing corruption, and strengthening and purifying party organizations. This too is something that has been endlessly discussed.

Says a senior Maoist leader, Dahal has confessed to the mistakes which damaged the party but there is no guarantee that he won’t repeat the same mistakes. The leader is not hopeful of the document’s implementation as Dahal remains completely focused on winning elections, come what may.

Says analyst Khatiwada, the Maoists do not have any distinct agenda with which to woo the public. So, for the Maoist party, the upcoming elections will be a survival issue. Without an electoral alliance, the party fears a humiliating defeat

So despite numerous differences with PM Deuba, Dahal is in favor of retaining the current coalition. Dahal has himself confessed that the Maoists cannot become the first party in the upcoming elections. At best, his goal will be to lock in the Maoists’ third-strongest position after NC and CPN-UML.

The Maoists are likely to forge an electoral alliance with CPN (Unified Socialist) but even their joint strength may be insufficient to defeat stronger parties like Nepali Congress UML. So, again, Dahal is pinning a lot of hope on a possible alliance with Congress.

But there are strong sentiments inside the NC that the party should not ally with the Maoists, even though there could be a tacit understanding to ensure the victory of some Maoist leaders. So, if NC remains rigid, Dahal could explore other alternatives, including an alliance with UML.

“This is our last chance to win the public’s hearts and minds by implementing the pledges we have made in the general convention,” says Maoist Central Committee member Bhandari. But even he is unsure of the continuity of the current ruling coalition.

‘ApEx for climate’ Series | Putting Nepal’s gen-next in climate lead

When 15-year-old Swedish environmental activist Greta Thunberg protested outside the Swedish Parliament in 2018, holding a sign saying ‘School Strike for Climate’, few took her campaign seriously. But she continued to bunk school to raise climate change issues.

Three years on, 18-year-old Greta is now at the center of a global climate change campaign, which in turn is an inspiration for adolescents across the world. Only now have global political leaders started to heed the issues she raised and she has become a beacon of hope for the younger generations, hammering home the message that world leaders need to act to preserve the earth from the menace of climate change.

Back in 2019, United Nations Secretary-General, António Guterres, in a meeting with Greta, said, “My generation has largely failed until now to preserve both justices in the world and to preserve the planet. It is your generation that must make us accountable to make sure that we don't betray the future of humankind.”

The COP26 conference held in November 2021 in Glasgow, Scotland, recognized the youth as critical agents of change. Additionally, the conference encouraged governments around the world to include youths as a part of national delegations in climate conferences.

Some policy documents of the Nepal government have also recognized the youth’s role on climate change issues. Nepal’s climate change policy introduced in 2019 states that “youth human resources will be mobilized by developing their capacity for raising awareness about climate change.” The policy further says youth researchers will be encouraged in climate change-related research and studies. Moreover, it talks about forming and mobilizing youth volunteer committees for climate-induced disaster management.

Also read: ‘ApEx for climate’ Series | Nepal makes its case. But to what effect?

The Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) presented by Nepal government in 2020 pledges to promote the leadership, participation, and negotiation capacity of women, indigenous peoples, and youth in climate change forums. The document talks about implementing the NDC through federal, provincial, and local governments, in collaboration with other relevant stakeholders including youth, women, and indigenous people.

International and national documents and frameworks have recognized the youth as an integral part of climate action. But what is the state of implementation? Are Nepali youths ready to contribute? What is the status of our youth’s participation in climate action?

According Radha Wagle, Joint secretary and head of Climate Division at the Ministry of Forest and Environment, youth involvement in climate-related policies and platforms is increasing but that is not enough. Wagle informs that four youths were inducted as members of the national delegation in the COP26 Summit. “We are also working on increasing the presence and contribution of youths in climate-related policy and implementation programs,” she adds.

Observers say young generations are not only at the receiving end of climate change but they can also play a vital role in addressing the issue. They can serve as agents of change and innovators in the action against climate. Over the past few decades, more and more youths are coming out to flag the issues of climate change.

Sagar Koirala, a youth climate activist, says the representation of Nepali youths in the climate change sector is low compared to other countries. “Only a few youths get to have their say in decision-making,” says Koirala. “No youth is consulted in major decision-making.” He says, as a youth climate activist, he wants to change this system and empower the youth. He stresses on the need for institutional mechanisms to empower a growing number of young people in climate action.

Also read: ‘ApEx for climate’ Series | Nepal in the middle of a climate crisis

At COP26, countries agreed to a new 10-year program of action on climate empowerment in order to promote youth engagement, climate education, and public participation. At the national level as well, the government should have policies to engage youths in all climate-related activities.

A few weeks back, ApEx had surveyed a random group of youths to gauge the level of their awareness about climate change. They had only a basic understanding of the issue.

In Nepal, youths began a systematic campaign on climate change only after 2008. There are now organizations advocating youth’s participation in climate action. For instance, the Nepalese Youth for Climate Action (NYCA), a youth-led coalition of the Nepali youths tackling climate change, was established in 2008 with a motto of ‘caring for climate change, caring for ourselves’. It has networks in various parts of the country.

Program Coordinator at Clean Energy Nepal, Lal Mani Wagle, who has worked as a youth climate activist, says there is much awareness on climate change among youths, at least in urban areas, compared to other areas of the environment. He says the government has recognized the youths who are working on climate change. “We can say youths have been contributing to climate action over the past decade,” says Wagle. “However, we are yet to systematize youth contributions in policy- and decision-making levels. It is a matter of satisfaction that government agencies are heeding youth suggestions.”

COP26 was not youth-inclusive

Prakriti Koirala

It had always been an ambition of mine to attend the Conference of Parties (COP) summit. Since elementary school, I had heard of the conference, procedures, and agreements. This year I got a chance to attend the COP26 in Glasgow, Scotland. I was lucky to have a party badge that allowed me access to all secret meetings.

From the perspective of a young person, the conference was not as youth-inclusive as we had expected. Fortunately, the participants representing the Nepali Ministry, CSOs, INGOs, NGOs, and youths as a whole worked well together. Nepali youths with party badges had the opportunity to participate in negotiations, while those with observer badges took part in various side events, sharing sessions, and the climate strike.

In my observation, youths from other countries, particularly in Africa, were leading their teams. They were in charge of preparing the drafts, negotiating with foreign governments, and attending various bilateral meetings. This impressed me and encouraged me to be well prepared, and made me realize that we as youths still have a lot of work. At the national level, many policies have addressed the voice of youths. However, we still have a long way to go in terms of involving youngsters in all aspects of climate change discussions and decision-making.

Koirala is a young climate activist

Youths are the most vulnerable group

Umesh Balal Magar

Climate change is an intergenerational problem caused by humans, mainly from the developed countries, and there is no silver bullet. Experts also say there is no science to cure the climate change problem but what we can certainly do is guide human behavior towards a more sustainable lifestyle.

Lack of political will is the main cause of climate change. Countries around the world are reluctant to implement solutions to combat the effects of climate change as they are too occupied with the goal of economic development, thereby increasing the emission of greenhouse gasses. That is exactly why we have failed for the 26th time to agree on a global solution at COP.

Also read: ‘ApEx for climate’ Series | How does Nepal get help in tackling climate change?

Nepal is one of the most vulnerable countries to climate change despite its small contribution to global CO2 emission. It has done some remarkable work on climate change mitigation policies. At COP26 in Glasgow, we stood firm in our commitment to net-zero emission and have prepared an exemplary NDC to remain steadfast towards that end.

Youths are the most vulnerable to climate change. In Nepal, we face all kinds of disaster threats like glacier lake outbursts, landslides and floods. Though youths are on the frontline of disasters, they are unlikely to make it to the policy-making table.

The Nepalese Youth for Climate Action (NYCA), a group of youth from all over the country, is working to protect Nepal and the Nepali people from adverse impacts of climate change by spreading awareness, advocating policies and taking action. We have been playing a key role in making Nepal more climate-resilient by leading adaptation efforts and through mitigation of GHGs since 2008. We work from local, national and international platforms for youth climate justice.

Magar is network coordinator, Nepalese Youth for Climate Action (NYCA)

2021: A year of politicization of democracy

A year of political turmoil and ‘politicization of democracy’, 2021 witnessed political parties and their custodians exploit democracy to weaken its basic tenets. Then-Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli dissolved the House of Representatives twice and each time defended his unconstitutional decision, saying fresh elections would buttress Nepali democracy.

Opposition parties dubbed Oli’s move “regressive” yet they too tried to influence the judiciary from the streets in the name of defending democracy. In fact, in 2021, all major political forces tried to use democracy to serve their personal or party interests.

Political analysts thus reckon there was an extreme politicization of democracy in 2021. PM Oli dissolved Parliament on 20 December 2020, and its repercussions were evident throughout 2021. The Supreme Court (SC) invalidated Oli’s move but that didn’t deter him from dissolving the House, again, in May 2021.

Political analyst Chandra Dev Bhatta says 2021 was “the year of politicization of democracy” as power-struggles among political leaders manifested in such a way that they started blaming each other for undermining democracy.

Each labeled the other ‘a threat to democracy’ and went to the extent of splitting their own party, says Bhatta. “In reality, they were only trying to hide their weaknesses.” Not only that, they went a step further and dragged the country’s neighbors into their mess, again all in the name of protecting democracy, adds Bhatta.

The year also saw a hollowing of democratic institutions. For instance, the Election Commission, an independent constitutional body mandated to hold elections and regulate political parties, was hamstrung due to political pressure.

The commission could not take a timely decision on the split of Nepal Communist Party owing to the due influence of political parties, an issue that was later settled in court. This clearly demonstrated compromising of the autonomy of constitutional bodies like the EC, undercutting their credibility.

Appointments in constitutional bodies sans parliamentary hearings came under national and international scrutiny. Appointments in the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC), for instance, drew national and international criticism and there were concerns about its independence. The United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, in an unprecedented move, even sought clarification from the commission over its autonomy and independence.

Also read: Will Deuba ditch the coalition for MCC?

Similarly, questions were raised over the appointment process and autonomy of other constitutional bodies.

Moreover, Nepal’s judiciary faced an unprecedented crisis this year. Probably for the first time in the country’s judicial history, SC judges launched a revolt against a sitting Chief Justice, bringing the judicial process to a grinding halt. CJ Cholendra Shumsher Rana was accused of trading court verdicts for political appointments. Similarly, there were accusations of corruption against other judges.

“The judiciary is the guardian of democracy. But then Nepal’s judiciary is in crisis, which means its democracy is also imperiled,” says advocate and another political analyst Dinesh Tripathi. He adds that the judiciary is on the verge of a collapse, and bad governance characterizes all state institutions.

The nexus between politicians and judges also deepened.

Political parties, on the one hand, tried to influence the judiciary to issue verdicts in their favor through street protests and other propaganda machineries. Supreme Court justices, on the other hand, hobnobbed with the politicians, to bargain for favors in exchange.

Similarly, the Parliament came under increasing executive pressure. The Parliament was dissolved twice, only to be revived each time by the judiciary’s help.

In another important development, there was a lot of bad blood between then Prime Minister Oli and Speaker Agni Prasad Sapkota. Several times, the government would close House sessions without consulting the speaker. The war of words between PM Oli and the Speaker affected the principle of separation of powers.

Even after the Parliament’s reinstatement, it was never allowed to function smoothly. The main opposition CPN-UML has been disturbing the House, raising questions over the Speaker’s role.

In fact, due to the executive’s constant inference, the Parliament’s role has been severely constrained. Both KP Sharma Oli- and Sher Bahadur Deuba-led governments showed their lack of commitment to parliamentary supremacy, for instance through the issuance of ordinances by skipping the House of Representatives.

Also read: Does Deuba’s victory mean early elections?

Most ordinances were issued to fulfill petty interests such as splitting parties or making political appointments.

Tripathi says there were attempts to cause massive damage to democracy. There were repeated attacks on the Parliament, the temple of democracy. “There were attempts at no less than to dismantle democracy but fortunately, it survived,” says Tripathi.

The office of the president was also dragged into controversy. President Bidya Devi Bhandari was accused of siding with then Prime Minister Oli instead of playing a neutral arbiter.

Along with the backsliding of democracy, the general public’s hopes for political stability—rekindled with the formation of a two-thirds majority government in 2018—were dashed. The window of stability had closed and 2021 had sowed seeds for another bout of political instability.

The powerful Nepal Communist Party (NCP) suffered a three-way split, which now means the chances of a single-party majority government is slim in the near future. NCP missed a historic chance of steering the country on the path of political stability and economic development.

Now, there is a fragile five-party coalition government that could crash any time, plunging the country into uncertainty.

Analyst Bhatta points out that the intra- and inter-party tensions that were the result of the leaders’ unchecked political ambitions have marred Nepali democracy. Over time, everything ended up in court and Nepal’s democracy became a “legal issue” and not a “popular one” based on people’s sovereignty.

If things go as planned, 2022 will see the start of three-tier elections. Timely elections could heal the damages inflicted upon democracy in 2021.

But advocate Tripathi isn’t optimistic as Nepali democracy is already on a shaky ground. “We can say democracy is on the verge of a collapse due to our weak state institutions. Even though the Parliament was reinstated, it is defunct. Moreover, it is no more a place to champion people’s voices and aspirations, which is not a healthy sign for our democracy,” says Tripathi.

This year the major political parties held their General Conventions electing new leaderships yet serious lapses were seen in their practice of internal democracy. Tripathi says almost all parties once again failed to ensure internal democracy, their long-standing vice. “There can be no democracy without internal party democracy,” says Tripathi.

What if… the 1923 Nepal-Britain treaty was not signed?

It was a watershed moment for the landlocked country precariously sandwiched between two ancient civilizations. Almost a century after the infamous Treaty of Sugauli (1816), Nepal and Great Britain had signed a new one in 1923 as its replacement. It was this new treaty that re-stated Nepal’s sovereignty in the international arena: it showed to the world that the UK, which effectively ran more than half of the world at the time, treated Nepal on an equal footing as a sovereign state.

Say observers, the treaty, now dead, deserves to be more widely discussed. Although the Treaty of Sugauli (1816) and the 1950 Peace and Friendship Treaty with India are endlessly discussed, historians and diplomats alike have only briefly taken up the 1923 treaty, often without highlighting its importance.

The treaty is important as, based on the same, Nepal restated its status as an independent and sovereign country in the international arena. Subsequently, in 1925, the treaty was documented in the League of Nations, the forerunner to the United Nations. It annulled the Sugauli and all previous treaties and allowed Nepal to conduct its foreign policy independently.

More importantly, Nepal used this treaty as a vital document while applying for UN membership in 1949, a year before it signed a peace treaty with independent India. In the application, it was stated that ‘Nepal has for centuries been an independent sovereign state and it has never been conquered, no foreign power has ever occupied the country nor intervened in its internal and external affairs’.

While applying for UN membership, Nepal also presented details of its diplomatic relations with Tibet, France, the US, India, and Burma.

Nepal informed the UN that the 1923 treaty explicitly ‘restated’ the country’s independence and sovereignty. But the application also maintained that, ‘the Government of Nepal has never considered that either the Treaty of Sugauli or any other treaties, agreements or engagements impaired its independence and sovereignty.’

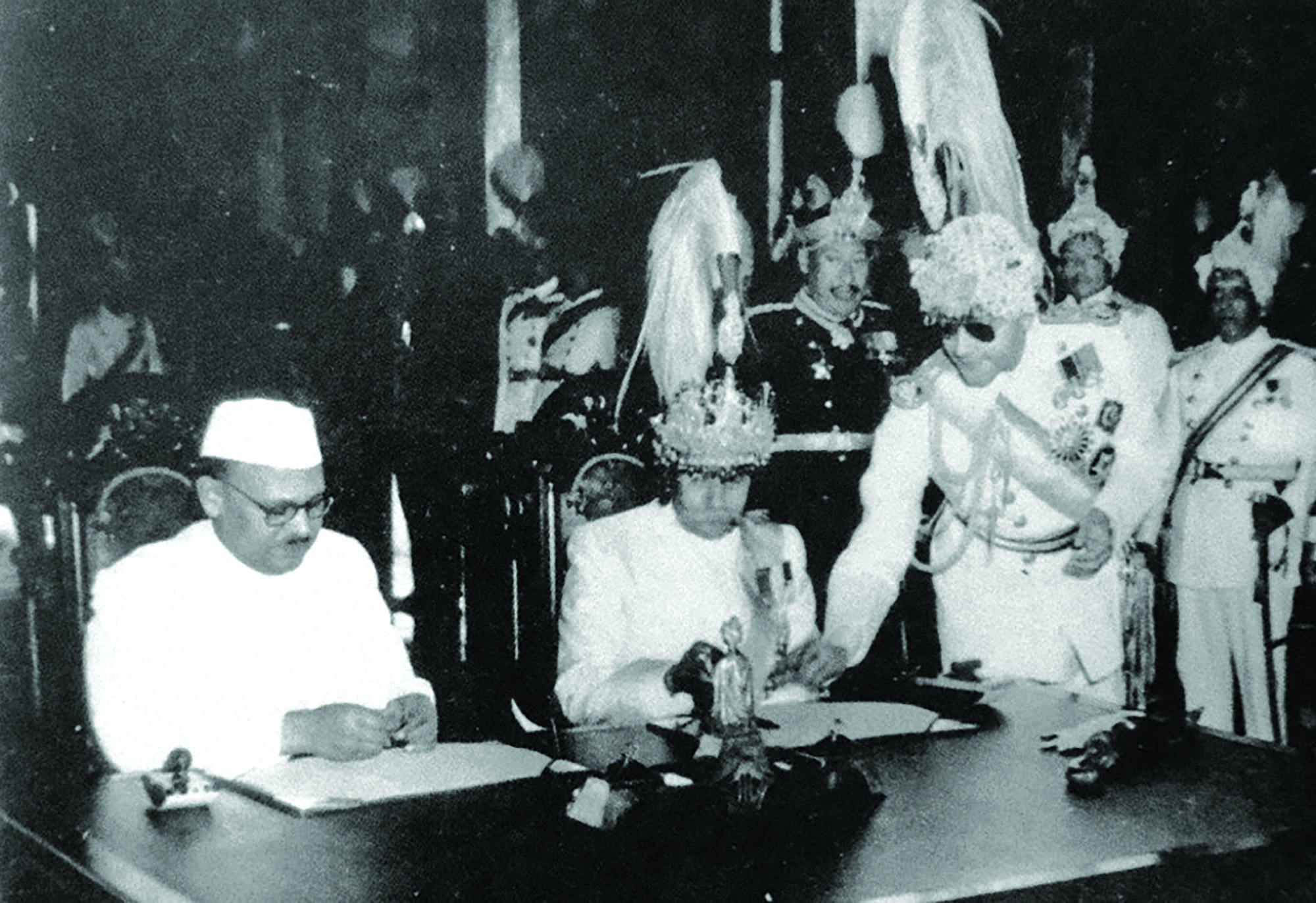

The signing of the India-Nepal Treaty of Peace and Friendship in 1950 by Prime Minister Mohan Shumsher Jung Bahadur Rana and Indian Ambassador Chandreshwar Prasad Narayan Singh.

The signing of the India-Nepal Treaty of Peace and Friendship in 1950 by Prime Minister Mohan Shumsher Jung Bahadur Rana and Indian Ambassador Chandreshwar Prasad Narayan Singh.

The treaty upgraded Nepal’s diplomatic status. With its signing, the status of the British representative in Kathmandu was upgraded to the level of Ambassador, which helped lift Nepal’s profile in the international arena.

Professor Rajkumar Pokhrel, head of Department of History, Tribhuvan University, says had the 1923 treaty not been signed, the tripartite agreement between India, Nepal, and the UK in 1947 may not have been possible. Similarly, there would have been no 1950 treaty between Nepal and independent India.

Nepal certainly has many reservations about the 1950 treaty and has been pushing for its amendment. But it was 1923 that laid the foundation for the 1950 treaty. The provisions of the two treaties are almost identical.

Historian Sagar SJB Rana says the similar provisions of the two treaties surprised him. Except for a provision which mentions equal treatment of each others’ citizens, other points are the same. So the basis of the 1950 treaty is clearly the 1923 treaty, Rana says.

According to historians, then Prime Minister Chandra Shumsher worked hard to get the British government to sign the treaty. Within a few days of becoming prime minister in 1901, Chandra Shumsher had dispatched a letter to British India seeking closer ties, giving a clear message that Nepal and Britain India are two sovereign nations and should be treated accordingly, says historian Rana. After becoming prime minister, Chandra Shumsher started to assert his position as the head of the government of an independent country while dealing with British India.

Chandra Shumsher JBR, Prime Minister (1901-1929).

In a recently published book titled Gaida’s Dance with Tiger and Dragon, political analyst Achyut Wagle writes of how the British government in 1920 accorded Chandra Shumsher with the honor of ‘His Highness’, which was “an implicit recognition of him as a prime minister of sovereign Nepal.”

Historian Rana says a Nepali ruler had never before gained such respect, and this translated into respect for his country’s status. Chandra Shumsher was later decorated with different British titles and honors. Soon after the treaty, the UK started addressing Nepal’s King as ‘His Majesty’, a title comparable to the one accorded to the British monarch. After that, other countries also started treating and respecting Nepal as an independent country.

At the same time, the British were thinking of rewarding Nepal for its contribution to the First World War. Nepal had contributed hundreds of thousands of troops and resources for the British war efforts, and the subservience to the British Empire helped Nepal be recognized as an independent state.

As a mark of gratitude for the Rana regime’s war-support, writes Wagle in the book, the British government in India, in March 1920, announced a support package of a million Indian rupees grant an annum and a one-time purse of Rs 2.1 million for Nepal.

All these developments show that the British government was gradually starting to recognize Nepal as an independent and sovereign country. As Chandra Shumsher was determined to sign a new treaty, preparations were taking place at the government level. When the Prince of Wales visited Kathmandu in 1921, Chandra Shumsher renewed his proposal for a new treaty. In his book, ‘Nepal Strategy for Survival’, Leo E. Rose writes of how the proposal met with a sympathetic response, and negotiations began in Kathmandu shortly thereafter.

Also read: What if… there was a referendum on Hindu state?

“Nevertheless, it took nearly two years of leisurely negotiations to produce a draft agreement for, as the British envoy noted, ‘there were… certain points both of principle and detail involved which required very careful consideration, and the weighing of literally every single word,’” Rose writes.

The treaty was finalized in 1923 after much consideration and signed in Singha Durbar the same year, ensuring that ‘Nepal and Britain will forever maintain peace and mutual friendship and respect each other's internal and external independence,’ among other provisions.

Following its signing, peace and tranquility prevailed at the border, says Dr Pokhrel, the historian, as the British were honest about its implementation.

Yet the 1923 treaty has its critics too. Writes Retd Major General of Nepal Army Purna Chandra Silwal Silwal in his book Nepal’s Instability Conundrum, “Although the treaty recognized Nepal’s independence for the first time in its history, the sovereign rights to import arms and ammunition from other countries were not fully respected. If the British government so desired, the provision would have been revoked. Hence, the British intention was to make Nepal submit.”

Historians say whatever the motivations for the 1923 treaty, on either side, Nepal probably would not be an independent state today without it. And Chandra Shumsher will forever get the credit for it.

Tika Dhakal

The 1923 treaty gave Nepal a unique identity

Named the “Treaty between the United Kingdom and Nepal”, its significance remains in its unequivocal recognition of Nepal’s external and internal sovereignty and independence by the United Kingdom, the world’s greatest power of the time. This treaty may be called foundational in that it gave Nepal the ability and basis to conduct independent foreign policy and bilateral relations with other countries. It was the only treaty of Nepal to be recorded in the League of Nations.

In the academic discourse predominantly focusing on the Treaty of Sugauli (1816) and the Nepal-India Treaty of Peace and Friendship (1950), it is worth remembering that several aspects of the 1923 treaty retain their importance. Today, the legacy of this treaty has been carried forward by the two treaties Nepal signed in 1950, with India and the United Kingdom respectively.

The substance of this treaty may be further interpreted in terms of the evolution of the concept of state in Nepal, which in the pre-treaty political context used to be associated with land being under the ruler’s possession. This notion of ownership based on Hindu traditions provided the ruler with inherent powers to collect taxes, exercise control and maintain order within the land possessed. The duality and interplay between the ruler and the people living in the land formed the essence of the concept of state, not only in Nepal but in the entirety of South Asia. This was so until the Westphalian concept of sovereignty arrived via imperial Britain.

Now enshrined in the UN Charter and universally accepted principle of the value-based international system, the idea of Westphalian state has transformed into the principle of equal sovereignty of states irrespective of the size of their geography, population and military. The modern state is therefore the reflection of human individuality. In addition to population, geography and legitimate government in internal contexts, sovereignty of a modern state is established externally on the basis of recognition it gets from the community of states. Although in veiled terminologies, literature on statecraft had formulated this element of sovereignty several centuries ago, as noted in Kautilya’s Arthashastra, which says that a state for its own protection would need friends, and friends may be gained or abandoned through treaties.

The 1923 treaty has also been criticized for perpetuating Nepal’s dependence and is termed unequal as the signatory on the Nepali side was Prime Minister Chandra Shumsher while signing it on the behalf of the UK was ambassador Willian Travers O’connor. But we have to see the larger picture leaving aside our ‘presentist’ biases. The treaty is certainly an important historical event that gave Nepal a unique identity as a modern state.

Dhakal is information and communication expert advising President Bidya Devi Bhandari and a PhD candidate in political science at TU

National Politics | Will Deuba ditch the coalition for MCC?

“I am in frequent talks with Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba. He is fully committed to keeping the current coalition intact. He has assured me that the coalition will stay alive till elections,” divulged CPN (Maoist Center) Chairman Pushpa Kamal Dahal at a public function on Dec 20. Although Dahal seems upbeat about the continuation of the five-party ruling coalition, challenges galore, say party leaders and observers.

Dahal’s statement itself indicates all is not well. The present government was not formed after an agreement on the Common Minimum Program (CMP) among its members. Instead, it was assembled as a political instrument to fight Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli, and so there are divergent views. When the CMP was finalized on August 8, a month after government formation, contentious issues such as the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) compact were skipped.

Baburam Bhattarai, former prime minister and leader of Janata Samajbadi Party, a coalition partner, speaking on Dec 20, minced no words in revealing that attempts are being made to undo the alliance. He pointedly said that if coalition partners fail to forge a common position on the compact, the current coalition could run into trouble.

In the coalition are Nepali Congress, CPN (Maoist Center), CPN (Unified Socialist), Janata Samajbadi Party, and Rastriya Jana Morcha. Among the five, there are no disputes over the compact inside the NC; the Maoists and CPN (Unified Socialist) want some amendments before endorsement; Janata Samajbadi’s federal council chair Bhattarai is in favor of endorsing it, while its chairman Upendra Yadav has some reservations. Meanwhile, the Jana Morcha is vehemently against the compact, but with a single seat in parliament, its position is largely irrelevant.

The coalition’s future largely depends on PM Deuba. Is he committed to keeping it intact? The PM does not give a straightforward answer to this, says a senior NC leader close to Deuba requesting anonymity. “PM Deuba is in favor of continuation of this coalition. But what happens if key national agendas such as the MCC compact do not move ahead and the government is embroiled in indecision and inaction?”

Also read: Does Deuba’s victory mean early elections?

To save the coalition, says the leader, Deuba has not pressed coalition partners to vote in favor of the compact, he just wants it tabled in parliament. NC senior leader Gopal Man Shrestha, who is also close to Deuba, says despite differences the coalition will remain intact “till the elections and differences over MCC will soon be sorted out.”

Coalition partners, however, fear that two issues—MCC and early elections—may bring Deuba and KP Sharma Oli closer, which obviously means the ruling coalition’s breakdown. Oli has hinted of his readiness of supporting the compact if coalition partners do not.

Says analyst Geja Sharma Wagle, PM Deuba is determined to get the compact endorsed by the parliament at any cost. PM Deuba’s first priority is consensus within the coalition, says Wagle. If that does not materialize, he might seek the opposition’s support.

Giving utmost priority to the coalition, PM Deuba has not directly reached out to Oli on the MCC or on parliament disruption. In fact, since the formation of his government, Deuba has not held a single one-on-one with Oli on national issues.

Many in NC believe the coalition must be kept intact in light of upcoming elections. If it fragments, leaders say, there are chances of communist parties coming together to defeat NC, as they did in 2017.

Due to the impending Nepali Congress General Convention, Deuba had been vacillating on vital decisions, including the MCC compact.

Now that he has secured party presidency for the next five years, coalition partners CPN (Maoist Center) and CPN (Unified Socialist) want an electoral alliance with the NC.

Ruling out cracks in the coalition, newly elected NC joint general secretary Jiwan Pariyar says the party will discuss all issues once the Central Working Committee gets a full shape.

Also read: Tracing the sources of Sher Bahadur Deuba’s power

Meanwhile, Dahal is buying time. On his proposal, a committee of Narayan Kaji Shrestha, Jalanath Khanal, and Minister for Communication and Technology Gyanendra Bahadur Karki has been formed to give advice on the compact.

A senior leader close to Deuba says, “Shrestha and Khanal have a distinctly anti-MCC position, so the committee’s formation is just a delaying tactic.” Similarly, Dahal has told Deuba not to push the MCC till the party’s national convention next week. However, there are strong voices inside the Maoist party that the MCC should not be endorsed, now or at any time in the future. Considering the Maoist party’s jamboree next week, the parliament has also been adjourned till January 2.

Some coalition leaders say that MCC should be touched only after national elections. However, the Americans have time and again conveyed that they will not wait so long. The board meeting of MCC on December 14 decided to wait for the time being as the Nepal government has committed to soon endorse it. In the first week of November, Deuba revealed that he and Dahal had written to the MCC, committing to early endorsement.

A later press statement from the MCC said, “MCC’s Board of Directors received an update and discussed the progress to date of the $500 million MCC-Nepal Compact”. The board made note of the commitment by the Government of Nepal. For a long time, parties have been discussing a resolution motion certifying that the MCC is not a part of the Indo-Pacific Strategy, to be tabled alongside the compact.

Speaker Agni Sapkota’s position on the compact is also creating distance between Congress and the Maoist party. According to sources close to him, the speaker has conveyed a message to Law Minister Dilendra Badu that he would not table the compact without an all-party consensus. On Dec 20, Badu met Sapkota to ask him to table the MCC bill in parliament. But there could be no agreement.

‘ApEx for climate’ Series | How does Nepal get help in tackling climate change?

As we reported two weeks ago, the effects of climate change are real and already visible in various sectors. Some mitigation and adaptation programs have been initiated but there is an urgent need to ramp them up.

As Nepal alone can’t fight the effects of climate change with its limited resources and knowledge, it needs to secure international support and cooperation. There is a need to build a wide international network through robust diplomacy, which in turn must focus on securing resources to gain access to the latest available technology, all in order to deal with climate-induced disasters.

So, the issue of climate change should be an integral part of the country’s engagement at bilateral, regional, and multilateral levels. However, except for participating in international platforms, Nepali diplomats don’t prominently raise the issue—the Ministry of Foreign Affairs doesn’t even have a mechanism dedicated to climate diplomacy.

In addition, seldom do the Ministry of Forest and Environment, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and the Ministry of Finance cooperate on climate change issues.

But politicians and bureaucrats are gradually starting to realize that climate should be a focal component of foreign policy.

Prabhu Budathoki, former member of the National Planning Commission (NPC) and a student of climate change, says there is a need for a nodal agency to deal with climate-related issues, both in and outside the country. “When I was an NPC member in 2017, I had lobbied for the creation of such an entity within the NPC to coordinate with all government agencies,” says Budhathoki. “Given the urgency of the matter, big countries have already started to appoint climate envoys, but we don’t even have a focal agency.”

Also read: ‘ApEx for climate’ Series | Nepal makes its case. But to what effect?

For the first time, Nepal’s foreign policy unveiled in 2020 incorporated a separate section on climate diplomacy. The policy envisioned Nepal’s proactive role in the policy formulation process of the United Nations and other international platforms for the acquisition of resources and technology for mitigation and adaptation plans. It also says Nepal shall lead mountainous countries to implement the principle of ‘polluters-pay’.

But, a key challenge, like always, is implementation. First, the Deuba government has not owned the policy introduced by the erstwhile KP Sharma Oli administration. New Foreign Minister Narayan Khadka publicly says he has initiated consultations to draft a new foreign policy.

To highlight Nepal’s issues and build an international network, the erstwhile government had initiated the Sagarmatha Sambad, a flagship annual international program to highlight Nepal’s agenda, including climate change. The event was planned for 2020 and a separate mechanism was set up for the same purpose—before it was postponed due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

After the easing of international travel, the Oli-led government had organized a conference just before the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change COP-26 to highlight Nepal’s agenda. But then the government changed.

Bimala Rai Paudyal, member of the National Assembly, who closely worked in the preparations of Sagarmatha Sambaad, says the current government has not owned up the initiatives of the previous government. Paudyal says the key purpose of such a dialogue was to invite world leaders to discuss pressing global issues and identity Nepal’s stand. “We had planned to hold the first dialogue on climate change to highlight the global climate issues as well as their effects on Nepal,” she says. The Nepal government had already invested millions in preparations and some invitations were also sent.

At COP-26, Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba committed to holding the summit, too, but to no avail.

Also read: ‘ApEx for climate’ Series | Nepal in the middle of a climate crisis

But Nepal should step up its diplomatic efforts, most vitally in carbon trade. Nepal’s forests store over 500 million tonnes of carbon and it is eligible to sell carbon credits to developed countries that want to offset their emissions.

The ‘mountain agenda’ is also not getting due attention in climate-related international negotiations. Though Nepal repeatedly urges the world to recognize specific climate vulnerabilities of high mountains, it has not been given priority in international policy frameworks.

Nepal has committed to achieving net-zero emission by 2045—a move estimated to cost $25 billion. Most targets set by Nepal are conditional: it can achieve them only with international support. But as Nepal graduates from the list of Least Developed Countries bloc, it will face additional hurdles in getting international support for its mitigation programs.

It is not only about finance. Nepal also needs to secure technological means and knowledge on capacity-building. The Green Climate Fund, Global Environment Facility, and Adaptation Fund are the potential fund sources . Similarly, there are bilateral/multilateral agencies and development partners before whom Nepal will have to display its capability to secure funds.

Issues related to loss and damage remain a key concern for Nepal. Addressing the COP26 Summit, Prime Minister Deuba said, “Loss and damage have become a key concern due to increased phenomena of climate-induced disasters. This subject must find a place under article 4.8 of the Convention. We call upon the Parties to agree on making Loss and Damage a stand-alone agenda for negotiations and support the framework of additional financing for it.”

Also read: Nepal’s COP26 commitments

Now, Nepal is raising this issue through the Least Developed Countries (LDC) group on climate change. The Least Developed Countries are 46 nations that are especially vulnerable to climate change but have contributed the least to the phenomena.

Similarly, Nepal is a member of the G-77 group on climate change issues. Activist Arjun Dhakal says Nepal’s climate diplomacy through the LDC group and G-77 is not yielding results. Instead of only relying on these platforms, says Dhakal, Nepal should start leading the climate change dialogue.

“For instance, we can lead the mountain agenda by bringing all mountainous countries, including India and China, on board,” says Dhakal. Dhakal also advocates for the formation of a separate entity to deal with climate diplomacy.

“We can create a separate mechanism under the Prime Minister’s Office by incorporating climate change experts and other technical manpower,” he says. Nepal needs to deal with major powers like the United States, United Kingdom, China, and other countries to secure their support.

Regional organizations such as SAARC and BIMSTEC could also play an instrumental role in highlighting Nepal’s agenda both regionally and globally. The problem is that the two organizations are now largely dysfunctional.

During the 18th SAARC summit in Kathmandu in 2014, member countries had discussed climate change. The declaration document says, “They [top executives of member countries] directed the relevant bodies/mechanisms for effective implementation of SAARC Agreement on Rapid Response to Natural Disasters, SAARC Convention on Cooperation on Environment and Thimphu Statement on Climate Change, including taking into account the existential threats posed by climate change to some SAARC member states.”

Yet again, the problem was in the implementation of the agreed goals.

Sagarmatha Sambaad: What and when?

The then foreign minister Pradip Gyawali inaugurating the office of Sagarmatha Sambaad on 22 November 2019 | Photo: Sagarmathasambaad.org

Sagarmatha Sambaad is a multi-stakeholder dialogue forum envisioned by the erstwhile KP Oli government to discuss issues of global, regional, and national significance. As a platform, it aims to bring together people from across the globe to shave and drive the discourses for positive change.

The Oli government had planned to organize this flagship program every two years by inviting heads of state/government, parliamentarians, policymakers, and local government representatives, as well as leaders from intergovernmental organizations, private sector, civil society, think tanks, academia, women, youths, and media to discuss ways of cooperation, exchange of ideas and sharing of experiences on prominent global issues.

The first edition of the program, scheduled for 2-4 April 2020 on the theme of ‘Climate Change, Mountains and the Future of Humanity’, was indefinitely postponed due to the Covid-19 pandemic. After the easing of Covid-19 restrictions, the erstwhile Oli government had made preparations to organize a ‘hybrid program’ (part-online, part-live). But the government fell and the dialogue was not a priority of the new Deuba government. According to sources at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, new Foreign Minister Narayan Khadka has been mum on the event.

Says Bimala Rai Paudyal, a member of the federal upper house who had worked in the preparations of the Sambaad, invitations were sent to dozens of heads of government and leaders. “As the new government did not follow through on our initiative, our resources have gone to waste and our international standing has been compromised,” she says.

Does Deuba’s victory mean early elections?

“If I lose party presidency, attempts will be made to remove me from the prime minister’s post.” So said Sher Bahadur Deuba ahead of the party’s election to elect its new leader. Prime Minister Deuba has been re-elected as Congress president, potentially helping him remain in power till the next elections. But what does Deuba’s victory mean for national politics?

According to Keshav Dahal, a political analyst who is also a leader of the Janata Samajbadi Party, the implications should be evaluated from two broad perspectives. First, is Nepali politics getting something new and transformative from Deuba’s election: creating new dimensions, charting a new political culture and agenda? “Surely not,” says Dahal.

Deuba’s re-election as party president clearly indicates a continuation of the status quo, says Dahal. “The same-old faces have been elected at the helm of major parties. So, the agenda of change and transformation has been sidelined.” KP Oli has been elected head of CPN-UML, and Pushpa Kamal Dahal ‘Prachanda’ is almost guaranteed to emerge as the undisputed leader of CPN (Maoist Center) again.

In the second perspective, we should evaluate the impact of Deuba’s reelection on current power politics, adds Dahal. Though things won’t drastically change on this front as well, say observers, Deuba’s handling of some key national issues could reshape power politics.

Inside the party, Deuba has emerged as a more powerful leader than before, which makes it easier for him to decide on key national issues at the party’s Central Working Committee. His traditional faction remains intact and now the party’s senior leaders Prakash Man Singh, Bimalendra Nidhi, and Krishna Prasad Sitaula are with Deuba as well. Long-time rival Ram Chandra Poudel, who did not fight for party presidency, is also likely to go soft on Deuba.

Also read: Tracing the sources of Sher Bahadur Deuba’s power

Deuba will have to deal with some national issues as party president and prime minister in the near future. America’s $ 500 million grant under Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) awaits parliamentary ratification. Deuba had long wanted to push this forward but waited till the party’s convention, as being pro-MCC could have affected his electoral prospects.

Deuba believes the parliament should be allowed to settle the MCC compact. Deuba may not face any opposition within the party to push the compact but it is not an easy task for him as prime minister. Two ruling coalition partners—CPN-UML and CPN (Unified Socialist)—are not in favor of endorsing the compact without amendment. A mishandling of the issue could well lead to a split in the coalition. However, Deuba has a history of taking bold and unpleasant decisions. If there is no consensus within the coalition, Deuba and the main opposition CPN-UML may come together to pass the compact.

“As the MCC compact is a major bone of contention among coalition partners,” says political analyst Puranjan Acharya, “it is going to become a defining challenge for Deuba”.

Deuba is believed to have won the party election after striking secret power-sharing deals with senior leaders like Krishna Prasad Sitaula, Prakash Man Singh, and Bimalendra Nidhi. Says political analyst Bishnu Dahal, as Deuba cannot accommodate all those leaders in power-sharing so he may opt for early parliamentary elections. But then his coalition partners are not in the favor of early elections.

Also read: General Conventions: Old parties, old faces

However, Deuba may also announce elections by dissolving the parliament if the main opposition CPN-UML continues to obstruct the parliament. UML has been obstructing the House, alleging the government and the parliament of illegally validating the earlier UML split.

Analyst Bishnu Dahal predicts a dissolution of parliament and announcement of new elections if the obstruction continues. Main opposition leader KP Sharma Oli has also been batting for early polls to justify his parliament dissolution.

Political Analyst Keshav Dahal agrees with Bishnu Dahal. “After being re-elected party chair, Deuba may also come to believe that instead of managing the complex coalition, early elections would be a more comfortable option,” he says. If Deuba dissolves parliament, UML is likely to support him.

Coalition partners CPN (Maoist Center) and CPN (Unified Socialist) are seeking an electoral alliance with Nepali Congress for parliamentary elections. However, big segments in the NC are against it, including such heavyweights as Shekhar Koirala and Gagan Thapa. However, the Maoist Center still wants to ensure an electoral alliance with Deuba, something Pushpa Kamal Dahal hinted at while addressing the inaugural session of NC’s 14th General Convention, saying that parties in coalition should stand together.

Deuba is in favor of an alliance with coalition partners, at least in some electoral constituencies. A senior leader close to Deuba also says that the party should be ready for some sort of electoral alliance with the Dahal- and Nepal-led parties to forestall the kind of broad leftist alliance last seen in 2017.

“As our politics is devoid of norms and values, it is hard to predict the kind of coalitions and alliances that could yet be formed,” says analyst Keshav Dahal.

What if… there was a referendum on Hindu state?

During the constitution drafting process, all major parties had agreed to adopt secularism, and mentioned the same in the first draft of the constitution taken to the public to solicit their views.

As the Constituent Assembly (CA) initiated voting on every article of the draft constitution, the pro-monarchist Rastriya Prajatantra Party (RPP) led by Kamal Thapa registered an amendment proposal, urging the House to vote in favor of Hindu state.

But the CA overwhelmingly voted down the proposal and reaffirmed Nepal’s secular status. Of the 601 CA members, only 21 voted in the proposal’s favor. This was a rare occasion when a Nepali parliament had voted on a religious issue.

At that time, RPP was the only political force that was vocally opposed to secularism. But almost seven years on, Thapa and his party are not alone in their bid to restore Nepal’s Hindu state. Some new political forces and sections of major parties are also doing so.

What if this issue is put to a vote? Though unlikely, the call for the restoration of the Hindu state seems to have gained momentum over the past few years. Although the constitution allows a referendum on a matter of national importance, the road to one is not easy; two-thirds of members of Parliament need to back the proposal.

Article 275, which envisages referendums, says, “If a decision is made by a two-thirds majority of the total number of the members of the federal Parliament that it is necessary to hold a referendum concerning any matter of national importance, the decision on that matter may be taken by way of referendum. Matters relating to the referendum and other relevant matters shall be as provided for in the federal law.”

If the Parliament decides to conduct a referendum, the Election Commission shall organize one, according to this constitution and the prevailing federal laws.

Former Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli performs a special puja at Pashupatinath Temple on 25 January 2021 | RSS

Former Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli performs a special puja at Pashupatinath Temple on 25 January 2021 | RSS

Hindu sentiments are prevalent in major political parties as well. The Nepali Congress as a party remains committed to secularism but there are demands within it for the restoration of the Hindu state. During the 2018 meeting of the Mahasamiti, the party’s second-most powerful decision-making body, over 40 percent of the delegates petitioned party leadership to amend Congress charter to address the issue.

Advocates of the cause within the party argue that people were not consulted on religion during the writing of the constitution. However, that issue never faded. Of the 1,600 party delegates assembled in Kathmandu for the meet, around 700 (over 43 percent) supported a signature campaign to press party leadership to re-establish Hindu state.

Shankar Bhandari, a central working committee member of the party who is leading its Hindu state campaign, says this agenda would be raised prominently during the close-door session of the party’s general convention set to start this week.

Bhandari says almost half of the representatives at the party’s Mahasamiti meeting in 2018 had backed a petition asking the leadership to make restoration of Hindu state an official party position. “We are fully convinced that the party will stand in favor of this proposal during the convention,” says Bhandari.

He says there’s no need to conduct a referendum, but even if one were to be held, people would overwhelmingly vote for a Hindu state.

Also read: What if… the domestic help industry were regulated?

Strong Hindu sentiments have also been observed inside the main opposition CPN-UML. As prime minister, from 2018 to 2021, UML chair KP Sharma Oli took a series of measures to placate Hindu sentiments, including installing a golden ‘jalhari’ at Pashupatinath temple. However, UML leaders and cadres are mostly mum on the matter. The political document endorsed by the party’s Statute Convention held in October fully backs secularism.

Says UML Chief Whip Bishal Bhattarai, even though some party leaders may raise the issue of Hindu state to seek votes, that is a non-starter. “If a referendum is held, the proposal for Hindu state will be easily shot down. Who will vote in its favor? As all parties seem committed to secularism, no amount of force can overturn this,” he says.

Inside the CPN (Maoist Center) led by Pushpa Kamal Dahal such voices are rarer still. There is limited discussion on the issue. Says former Constituent Assembly member and Maoist leader Lucky Sherpa, “some political parties are trying to use religion as a political tool. Yet they are mistaken if they think they can get votes with this agenda.”

The Maoist leader from a marginalized community says that there is no need for a referendum as the constitution has already cemented secularism and religious harmony. “Why should we hold a referendum on an issue that’s already done and dusted with?” she pointedly asks.

On July 26, Rabindra Mishra, a veteran journalist who now leads the Bibeksheel Sajha Party, had proposed dismantling Nepal’s federal structure and holding a referendum on secularism. His proposal attracted fierce criticism from advocates of secularism, both in and outside the party.

The then Sajha Party had, through its national convention held in Lumbini in 2020, unanimously passed a resolution demanding a referendum to decide the fate of secularism. In his political document titled ‘Changing Course: Nation above Notion’ Mishra had argued that in a country with 80 percent Hindus, the result of a referendum is a foregone conclusion in favor of the Hindu state.

“Many surveys have confirmed this. Secondly, if public opinion is not honored in matters like these, there will be a silent fire of dissension ever-present in the minds of the overwhelming majority, which can explode at some point in the form of extremism or ultra-nationalism,” he says.

The RPP, which concluded its general convention recently, has been raising the issue of the Hindu state for over a decade, if without enough public support.

Now that Rajendra Lingden has been elected RPP chair, there are reports that he has strong backing of King Gyanendra. Under Lingden’s leadership, according to party leaders, the Hindu state revival campaign will gain momentum.

Kamal Thapa, who was defeated by Lingden, has publicly accused Nirmal Niwas (King Gyanendra) of orchestrating his defeat.

Speaking after his victory, Lingden said: “There is a huge Nepali mass that wants to revive Hindu state and monarchy. I will connect them to my party. The revival of the monarchy and the Hindu state is my key priority.” There is widespread speculation that Gyanendra wants to revive the RPP to launch the Hindu state campaign.

Also read: Referendum on secularism? 10 public intellectuals weigh in

Then there is the external factor pushing for the revival of the Hindu state in Nepal. Over the past few years, India’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has been reportedly suggesting Nepal’s political parties to take measures to protect the Hindu religion. As BJP enhances relations with Nepali parties, the Indian Hindu nationalists have been increasingly critical of Nepal’s loss of its Hindu status.

In a meeting with some NC leaders in the first week of October, Yogi Adityanath, chief minister of Uttar Pradesh, reportedly urged the party to strengthen ‘cultural nationalism’. BJP Spokesperson Vijay Sonkar Shastri, who was in Nepal in November, predicted that Nepal would sooner or later become a Hindu state.

Speaking to media persons in Pokhara, he said Nepal was a Hindu nation and it will remain so. “BJP leaders are cautioning their Nepali counterparts to take measures to curtail religious conversions seen under the new secular dispensation,” an NC leader says on the condition of anonymity.

Various Hindu organizations are also pitching for the Hindu state’s revival. Last year, just before the KP Sharma Oli dissolved the Parliament, a series of protests erupted across the country demanding the revival of the monarchy and Hindu state.

Asmita Bhandari, general secretary at World Hindu Federation, is obviously in favor of the Hindu state. However, she has a different take on the referendum. Says Bhandari, Nepal was converted into a secular state through a political decision, so the same method should be applied to revive the Hindu state.

Also read: What if… the 2015 constitution had been delayed?

“When the Constituent Assembly endorsed the first draft of the constitution, more than 85 percent people were in favor of a Hindu state. But a report saying so was hidden,” she says.

Even if a referendum were held, says Bhandari, an overwhelming majority will stand for the Hindu state. “There is no doubt, 80 percent of people are in favor of a Hindu state,” says Bhandari.

In a public opinion poll conducted earlier this year by Sharecast Initiative Nepal, a NGO, 51.7 percent respondents—slightly down from a 15-year average of 60 percent—said Nepal should be declared a Hindu state, 40.3 percent said they are okay with secularism, while 8.1 percent respondents withheld their views. According to the survey, the support for Hindu state, at around 70 percent, is the highest in province no. 2.

As Pitambar Bhandari, Assistant Professor at the Department of Conflict, Peace and Development Studies of Tribhuvan University, sees it, the Hindu sentiment has risen somewhat in the past few years.

According to him, the biggest reason is political parties’ failure to properly manage the political system established by the new constitution.

Additionally, for many people, “advocating for a Hindu state has become a medium of expressing their dissatisfaction, which is precisely why some political leaders want to milk the agenda,” says Bhandari.