SAARC: The past, present and future

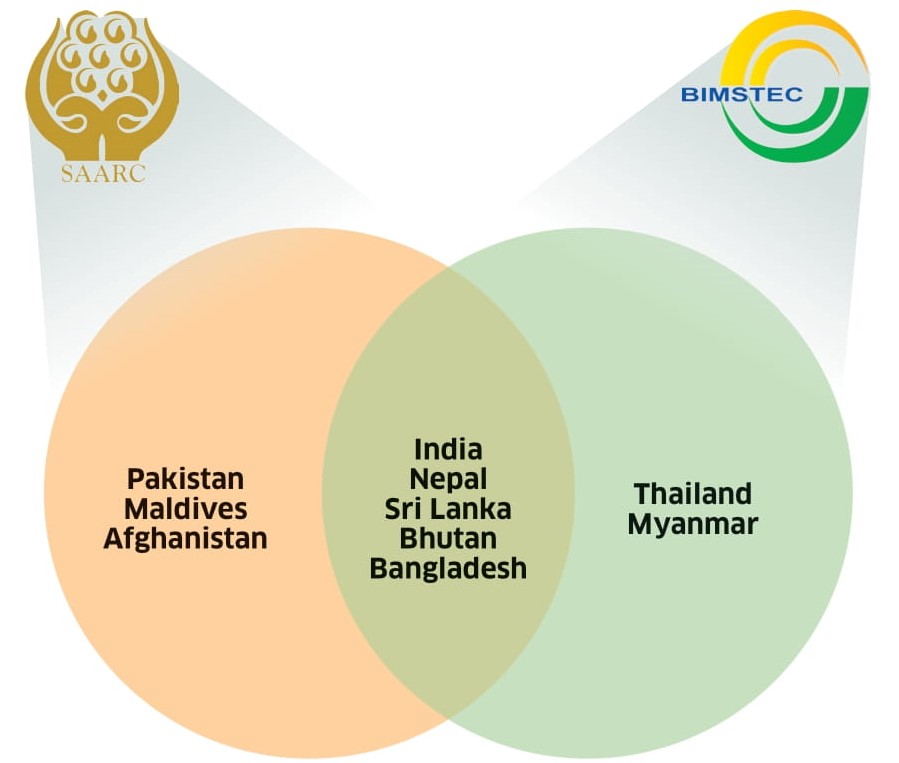

Many reckon the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) is dead and there is no point in flogging a dead horse. Perhaps. As India, by far the biggest South Asian power, is more interested in alternative forums like the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral and Technical Cooperation (BIMSTEC) and the Bangladesh-Bhutan-India-Nepal (BBIN) initiative—both without Pakistan—it may be wise to go along with the regional behemoth. BIMSTEC just came up with its charter. Granted. Yet it is not without reason that smaller South Asian countries like Nepal and Bangladesh that played a vital role in SAARC’s formation want to retain and revitalize the regional body.

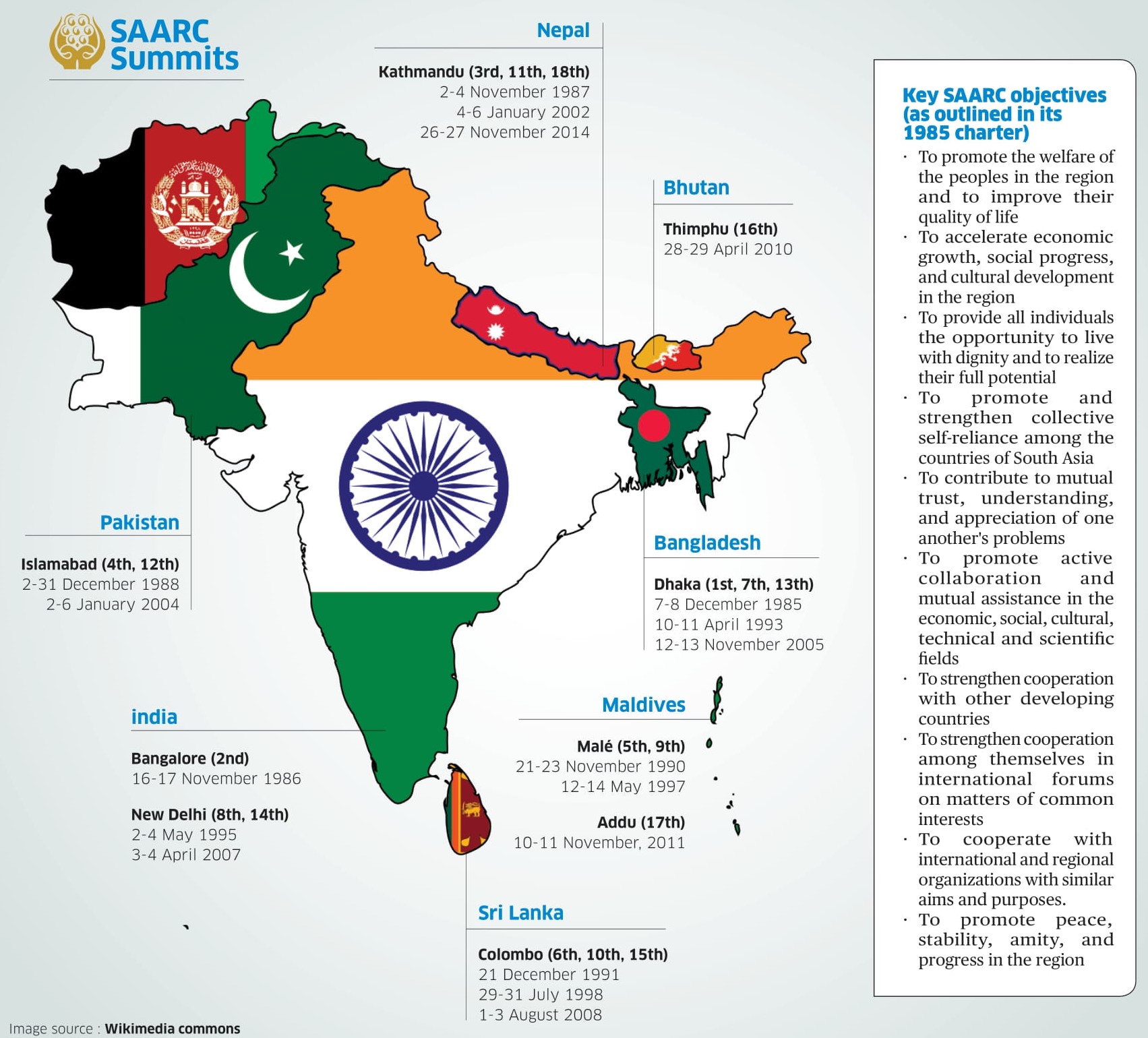

SAARC came into existence in 1985 at the initiative of Bangladeshi President Ziaur Rahman, with unstinted backing and lobbying of Nepali King Birendra. In the Cold War-era, it was common for the US and the USSR, competing superpowers at the time, to try to create blocs of influence. SAARC came into being partly because of the American desire to keep South Asia out of the Soviet grasp—even as India-USSR relations were warming. But SAARC would not have materialized had the smaller South Asian countries not felt the need to collectively bargain for their socio-economic development with the richer world.

SAARC is dear to the likes of Nepal, Bangladesh, Bhutan and Sri Lanka because their leaders have over the years identified with its rationale even as India and Pakistan, the two feuding big powers in South Asia, have not always looked at SAARC kindly.

According to Lailufar Hasmin of the University of Dhaka, “Bangladesh felt that a stable and powerful South Asia was required to ensure its own development. The idea was later crystalized in the organization of SAARC.” Perhaps the same words could be repeated in Nepal’s case.

The idea was that if the region was not consolidated, she adds, its countries could never achieve their potential. This was true in 1985 and it is true today.

Full story here.

SAARC: The original sin or salve?

The South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) was formed to overcome common regional challenges like pervasive poverty, under-development, and lack of jobs.

Since its inception in 1985, geopolitics in the region and the world at large has drastically changed. But SAARC has made little progress in this time as its key objectives remain unfulfilled.

The 19th SAARC summit, scheduled for Pakistan in 2016, was cancelled after India accused Pakistan of a “terrorist attack” on its soil. The regional body has since been moribund.

Cold War impetus

The Cold War was instrumental in SAARC’s formation. Many regional organizations came into existence at the behest of the Western world at the time, including the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). The formation of this Southeast Asian body in 1967 added to the impetus for a similar regional body in South Asia.

In his book ‘Regional Cooperation in South Asia Emerging Dimension and Issues’, Prof BC Upreti of India says that during the Cold War both the US and the USSR encouraged countries across the world to build regional organizations to increase their influence.

Backed by Western countries, many regional organizations such as the Rio Pact, the Organization of American States in Latin America, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), and the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization came into being at the time. Their main objective was to protect their politico-strategic interests and to contain the Soviet influence, Upreti writes in his book.

The Soviets also supported the formation of regional bodies of its allies like the Warsaw Pact in Eastern Europe. The two sides in the Cold War wanted to increase their influence through these regional organizations. And the US in particular was keen on getting the countries in South Asia to form a regional organization.

Foreign policy expert Dev Raj Dahal says the talk of regional bodies gained momentum in South Asia in the 1970s.

“The US urged the countries of this region to form a regional body. It first helped form SAARC and later to bring in Afghanistan as its member,” Dahal says.

But it was only in 2007 that the US formally joined SAARC as an observer country. Since then, the US has been continuously expressing its readiness to work on regional integration and connectivity.

China became a SAARC observer country in 2005. It too had of late shown an interest in the regional body, perhaps to expand its sphere of influence in the region.

The other SAARC observers are Japan, South Korea, Myanmar, Mauritius, Iran, Australia, and the European Union.

Regional necessity

The formation of SAARC, however, wasn’t just predicated on Cold War-era politics of regionalism. Its existence was also necessitated by the fact that small South Asian countries needed recognition on the global stage in order to tackle their socio-economic problems. Formation of a community of nations with common interests, they reckoned, would strengthen their voice on the international arena. Together, they could fight poverty and underdevelopment.

Initially, it was Nepal and Bangladesh that strongly pushed for an inter-governmental regional organization at various regional and international platforms, says Dahal.

Addressing the 26th Colombo Plan Consultative Committee Meeting in Kathmandu in 1977, then King Birendra had proposed a regional body to utilize Nepal’s untapped hydropower potential.

At that time, King Birendra had also talked about incorporating China into such a regional body.

But it was then Bangladeshi President Ziaur Rahman who first took the initiative to form SAARC.

Lailufar Yasmin , professor at University of Dhaka, says as a newly independent country, Bangladesh espied the vulnerability of the regional architecture as India and Pakistan were looking beyond the region to ensure their security.

“Bangladesh felt that a stable and powerful South Asia was required to ensure its own development. The idea was later crystalized in the organization of SAARC,” she says.

The idea, she adds, was driven by the concept of regional co-development: if the region is not consolidated, went the idea, its countries could never achieve their potential.

Rehman floated the first concrete proposal before other countries in the region on 2 May 1980. Before that, he had proposed the idea to the then Indian Prime Minister Morarji Desai in 1977. He had also shared it with the leaders of Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka during his visits to these countries.

Moonis Ahmar, a Pakistan-based expert on international relations, says formal negotiations among countries to form SAARC began in early 1980s.

“The first meeting of foreign secretaries of South Asia was held in 1981 and the first meeting of foreign ministers in 1983, leading to the first summit of the regional body,” says Ahmar.

At first, both India and Pakistan were skeptical. India was suspicious that smaller countries in the region could use the regional body to gang up against it. Pakistan, on the other hand, saw SAARC as part of an Indian conspiracy to spread its influence in the region.

At the time, King Birendra had played a pivotal lobbying role. After Bangladesh floated the proposal, he dispatched foreign secretary Bishwa Pradhan to the countries in the region to lobby for the formation of SAARC.

In 1980, the foreign ministers of all seven countries met on the sidelines of the United Nations General Assembly and agreed to prepare a concept note for SAARC.

While preparing the note, the concerns of India and Pakistan were assuaged by picking non-political and non-controversial areas for regional cooperation.

After that, there were a series of meetings to hash out the nitty-gritty.

According to former foreign minister Bhek Bahadur Thapa, King Birendra took the leadership for the formation of the regional grouping.

“Initially, India was reluctant to form such a regional body. It was concerned that smaller neighboring countries could use SAARC to exert collective pressure on it on select issues,” says Thapa.

But King Birendra was dead against unequal treatment of small countries by big ones, says Thapa: “He wanted a regional body to overcome such unequal treatments.”

The collective spirit of small countries was amply reflected in the declaration of the first SAARC summit in Dhaka on 7 and 8 December 1985. It says: “They considered it to be a tangible manifestation of their determination to cooperate regionally, to work together towards finding solutions towards their common problems in a spirit of friendship, trust, and mutual understanding and to the creation of an order based on mutual respect, equity and shared benefits.”

Thanks to King Birendra’s active lobbying, member states also agreed to set up the SAARC Secretariat in Kathmandu.

Since its establishment, Nepal has been trying to make it a result-oriented organization. The country has also been serving as the chair of the regional body since 2014.

With the 19th SAARC summit indefinitely postponed over India-Pakistan tensions, Nepal has been urging the two countries to create a suitable climate for the summit. But nothing has come of it.

Pakistan has accused India of obstructing the SAARC process. India, meanwhile, doesn’t seem interested in taking SAARC forward. It has instead prioritized the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC), of which Pakistan is not a part.

Already, many Indian international relations experts and leaders see BIMSTEC, an international organization of seven South Asian and Southeast Asian countries, as an alternative to SAARC.

The risks and benefits of electoral alliances

In principle, the five ruling parties have agreed to forge an electoral alliance for the May 13 local elections. In recent weeks, top leaders of these parties have been meeting almost daily to agree on the alliance’s modus operandi. But nothing has come of it so far.

The intra- and inter-party dynamics are constraining top leaders’ wishes to cement the alliance. The rival Nepali Congress faction led by Shekhar Koirala is dead against any kind of electoral partnership with the left forces, putting the party leadership in a fix.

Similarly, there are strong sentiments in the Congress rank and file against such an alliance. They reckon that allying with the left forces could weaken the party’s base in the long-run.

Already, party members have warned leadership against a poll alliance with left forces in Chitwan.

In the 2017 elections, the NC had supported Maoist candidate Renu Dahal (daughter of Maoist Chairman Pushpa Kamal Dahal) for the post of mayor of Bharatpur Metropolitan City, Chitwan, much to the chagrin of party cadres.

The Maoist party again wants to ally with the Congress in Bharatpur, but the party’s Chitwan district chapter has decided to field its own candidate. They say they will this time not be forced into supporting a candidate from other parties.

It remains to be seen how the Congress leadership will assuage its cadres in Bharatpur and other local units across the country.

Congress President and Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba knows forging an alliance with the left parties is going to be complicated, but he wants to do it anyway.

If the ruling coalition partners are not offered an olive branch, he fears, they could band together with the main opposition, CPN-UML, which could reduce Congress votes in the national elections.

At this point, Ram Chandra Poudel, former rival of Deuba for party president, is the only top Congress leader who whole-heartedly supports the idea of poll alliance.

The potential alliance has also been hindered by the fact that the CPN (Maoist Center) and CPN (Unified Socialist) are finding it hard to gauge their local-level strength to bargain for seats with the main ruling party.

In the 2017 local elections, of 753 local units, the Maoist party had won in 106 through alliances with different parties.

At the time, there was no discussion of a national-level electoral alliance, unlike this time.

Meanwhile, the Unified Socialist is a new party formed after a split in the UML. Around 10 percent of the UML elected representatives have joined the Unified Socialist and its local strength remains a mystery.

A senior Maoist leader says despite marathon talks at the top level, there has been no progress on the modality of poll alliance, nor has there been any agreement on seat-allocation. “I am not hopeful of a formal alliance,” says the leader, who didn’t wish to be named.

He speaks of the difficulty of working with the Congress at the local level as the ideology, orientation and thinking of the two parties are polar opposite.

“We are not sure the Congress supporter will vote for Maoists candidates, or vice-versa,” he says.

Maoist leader Dev Gurung says second-rung leaders will work on the modality of alliance when top leaders reach an agreement.

One option ruling parties are discussing is forging an alliance based on the 2017 poll results. The Maoists and Unified Socialist are of the view that in the case of six metropolitan cities and 11 sub-metropolitan cities, the decision on alliance should be taken from the central level. In other municipalities, they suggest, local leadership can decide.

To facilitate the electoral partnership, the five-party alliance on April 5 formed a cross-party panel, led by senior Congress leader Poudel. To manage resistance at the local level, the Congress is encouraging its leaders in provinces and districts to explore the possibility of alliance through consultations with other parties.

The five parties have decided to forge an alliance in more than two-dozen districts. As they are still talking, the Congress has instructed its local level leadership to delay the process of finalization of candidates.

In 2017, the central leadership had not fixed such alliances, even though there were some partnerships at the local level. The Maoist party had allied with the UML, NC, and Madhes-based parties.

Of 753 local units, the UML had won in 292, the Congress in 263, and the Maoists in 106.

After the 2017 local poll results were publicized, UML forged an alliance with the Maoists in the parliamentary elections to beat the NC. The two left forces then went on to merge to form the Nepal Communist Party (NCP). The party broke down a little after a year, which not only revived the erstwhile UML and Maoist Center but also gave birth to a third offshoot, Unified Socialist, led by Madhav Kumar Nepal.

Political analyst Krishna Khanal says the Maoists and Unified Socialist are seeking electoral alliance because they feel insecure about their electoral prospects. “The two parties are facing an existential crisis and are desperate to forge an electoral alliance,” he says.

Despite its alliance in the previous elections, the Maoist party didn’t fare well, and the Unified Socialist is facing elections for the first time.

It is not just the Maoists and Unified Socialist who are desperate for an electoral alliance though. In truth, the NC also needs these parties’ support to beat its main rival UML.

If the communist forces were to come together, it would be difficult for Congress to even replicate the results of 2017; there was no left alliance at the time of the last local elections.

Deuba is trying to cajole his party leaders and cadres into a poll alliance, reminding them of the defeat Congress faced in the 2017 parliamentary elections due to the left alliance.

But some observers say it is better for the parties’ long-term prospects to fight elections separately.

“An electoral alliance may benefit some parties in the short-term, but it would be detrimental to the long-term party-building process,” says Puranjan Acharya, a political analyst.

Political experts reckon a high number of political parties is encouraging the culture of electoral alliances. They say each political force views elections through its own narrow prism.

“We have more parties than we can sustain. We have to bring down their number, which in turn will be a departure point for political stability,” says Bhojraj Pokharel, former chief election commissioner.

Nepal’s electoral alliances are not based on similarities in ideology, conviction and belief, he says.

“Rather, they are purely driven by the intent of getting good electoral outcomes. Forging such electoral alliances does not guarantee their longevity,” Pokharel says. “Alliance among like-minded political parties is natural but among opposite forces is not.”

What if… the left electoral alliance is revived?

A neck-and-neck competition is expected between Nepali Congress and CPN-UML, the two major parties, at the upcoming local, provincial as well as national elections. To best the other, each party will need the support of a third party, preferably the CPN (Maoist Center) or the CPN (Unified Socialist).

This is exactly what UML Chairman KP Oli did in 2017 to ensure the drubbing of Congress. To forge a left alliance, Oli had offered 40 percent seats to the Maoists under the first-past-the-post (FPTP) electoral system. It was a master-stroke: the alliance secured nearly two-thirds seats in national parliament and went on to form governments in six of the seven provinces.

Later, in order to prevent Maoist Center Chairman Pushpa Kamal Dahal from allying with the Congress, Oli merged his party with the Maoists to form the Nepal Communist Party (NCP)—in what was the largest and most powerful leftist party in Nepal’s political history.

But the unity didn’t last. The party split in 2021 due to power-tussles in the top leadership and the former constituent parties, UML and Maoist Center, were revived. Moreover, the Madhav Kumar Nepal faction of the UML also parted ways with Oli and formed the Unified Socialist.

With another election season approaching, the current political dynamics resemble that of 2017. Oli wants to return to power by securing majority votes, both in local and parliamentary elections. Second-rung UML leaders like Ghanashyam Bhusal and Raghuji Pant are advising Oli that the party can secure electoral victory only through an alliance with like-minded parties.

Oli, meanwhile, has ruled out such unification. “There is no chance of left unity, but there could still be an electoral alliance,” Oli told the party’s central committee on March 23.

Some UML leaders say Oli has rather adopted a strategy of stealing leaders and cadres from the Maoists and the Unified Socialist to weaken the two parties.

A UML leader, who spoke on condition of anonymity, told ApEx that while Oli is not in favor of striking a deal with Maoist party like he did in 2017, he does realize the importance of a poll alliance.

“He knows that if the current ruling coalition remains intact in the elections, the UML won’t be able to return to power,” says the leader.

Oli appears more flexible on forging an alliance with the Maoists than with Nepal’s Unified Socialist: he hasn’t forgiven Nepal for his role in splitting the UML.

Oli’s strategy, therefore, is centered on an electoral alliance and a coalition government—not in merging with another party, something which in the past invited many complexities.

Senior journalist Sitaram Baral says snubbing the possibility of a left alliance or unity will be a strategic blunder for UML—and Oli is aware of this. But he also needs to tread carefully to bring the UML back to power.

“Oli has of late been using harsh words against Dahal, which will only push Dahal closer to Congress,” says Baral, who has closely followed Nepal’s left politics for over two decades.

The UML as well as the Maoist Center have become weak after the party split. The UML got weaker still after its senior leaders Nepal and Jhala Nath Khanal walked out to form the Unified Socialist. The Maoist Center, on the other hand, has lost influential leaders like Ram Bahadur Thapa and Top Bahadur Rayamajhi who chose to remain in the UML when the NCP split.

The disharmony among communist parties has served the Congress well. The threat it sensed from its main rival, UML, has largely been tempered.

To prevent the Congress from becoming the first party again, second-rung leaders of both UML and Maoist Center are trying to convince their respective leaderships to unite for elections.

Maoist leader Haribol Gajurel says there is pressure on Dahal to revive the left unity.

Inside the Maoist party, the likes of Barsha Man Pun, Dev Gurung, Krishna Bahadur Mahara and Narayan Kaji Shrestha have been pressing their leadership on a leftist electoral alliance.

Even in the run-up to the 2017 elections, such second-rung leaders of the two parties had played a pivotal role to build an electoral alliance. Multiple sources confirmed to ApEx that these leaders have been frequently meeting Oli and Dahal to convince them to contest upcoming elections as a team.

Even China wants to see the left forces in Nepal reunite. When a fissure emerged in the NCP after the then PM Oli dissolved the House of Representatives in December 2021, China had sent its Vice-Minister of the International Department of the Communist Party of China (CPC) Guo Yezhou to prevent the party-split.

China wants in Kathmandu a stable government led by communist parties, which will not tilt toward India or western powers. The northern neighbor has been encouraging Nepal’s communist parties to unite since the 2008 abolition of monarchy.

There has also been frequent exchange of visits between CPC officials and Nepal’s communist leaders over the years.

Most recently, UML Vice-chairman Bishnu Poudel led a team to China to meet their communist counterparts. Maoist leader Dev Gurung also flew to China on March 25 along with other party leaders. Observers see these visits as China’s way of wooing Nepal’s communist parties and trying to reunite them.

China views the Congress as a pro-Western party that doesn’t want to cooperate with Beijing.

Congress Party President Sher Bahadur Deuba wants to forestall a left reunion at any cost. To this end, he has been assuring the left coalition partners on a possible electoral alliance.

If the NC does not offer an olive branch to Dahal and Nepal, Deuba suspects, the communist parties will forget an alliance, to the detriment of Congress in upcoming elections .

Deuba told the party’s Central Working Committee meeting on March 25 that an alliance with the left parties would ensure Congress victory.

However, senior Congress leaders like Shekhar Koirala and Dhan Raj Gurung are against an electoral alliance with left forces. They are of the view that the Congress can win elections on its own. They say, alliance or not, traditionally communist voters will always be reluctant to vote for Congress.

Nain Singh Mahar, a CWC member of Congress who is close to Deuba, says the party leadership is cautiously weighing the issue of electoral alliance.

“We should have an understanding at the local level in order to forge an alliance and we are working towards that end,” he says. The Maoist Center and Unified Socialist leaders are open to overtures from the UML if the NC is not keen on retaining the ruling alliance.

Dahal has publicly said that if the Congress “pushes them into a corner,” his party will have no qualms allying with the UML. But the priority, he said, would be to retain the alliance with the Congress.

Top leaders from the Congress, the Maoist Center and the Unified Socialist have been working on a modality of alliance at the local level, but there hasn’t been much progress.

Political analyst Bishnu Dahal says having an electoral alliance among left forces won’t be easy—what with emerging geopolitical dimensions.

He says if communist parties try to come together, external forces may encourage Prime Minister Deuba to dissolve the Parliament and scuttle scheduled elections.

“India, the US and other western powers don’t want to see a united communist force in Nepal,” he says.

He also foresees another scenario: “If Deuba rejects electoral alliance, Dahal and Nepal may withdraw their support to the government in order to postpone elections.”

Even if an alliance for local elections does not materialize, say political analysts, one is likely during parliamentary elections.

Political analyst Puranjan Acharya says local election outcomes may prompt parties to rethink alliances for national elections.

The Congress will profit if the left parties fight elections separately. But if they unite, Acharya says, the ruling party could again see a repeat of 2017.

“In the previous elections, around 60 percent of voters cast their votes for communist parties. The Congress got 31-32 percent votes, which has not increased,” he says.

Journalist Baral also says in case of a left electoral alliance, they could still get an overwhelming majority and form a government, again sidelining the Congress.

“The NC is likely to slightly increase its popular-vote percentage,” he says. “A left alliance, on the other hand, may not be as effective as it was in 2017, but it will still emerge as a potent force.”

In 2017, under the FPTP category, of 165 seats, the UML won 121 (33.25 percent), the NC 63 (32.78 percent), and the CPN (Maoist Center) 53 (13.66 percent).

In terms of percentage, the UML and NC have near equal strength, making them main competitors. With the ever-present prospect of left unity, there are already discussions of a two-party system.

One of its proponents is Shankhar Pokhrel, the UML general secretary.

Speaking at a function on Feb 27, he had said that the country should opt for a two-party system (left and democrat).

“More parties mean more political instability,” he said.

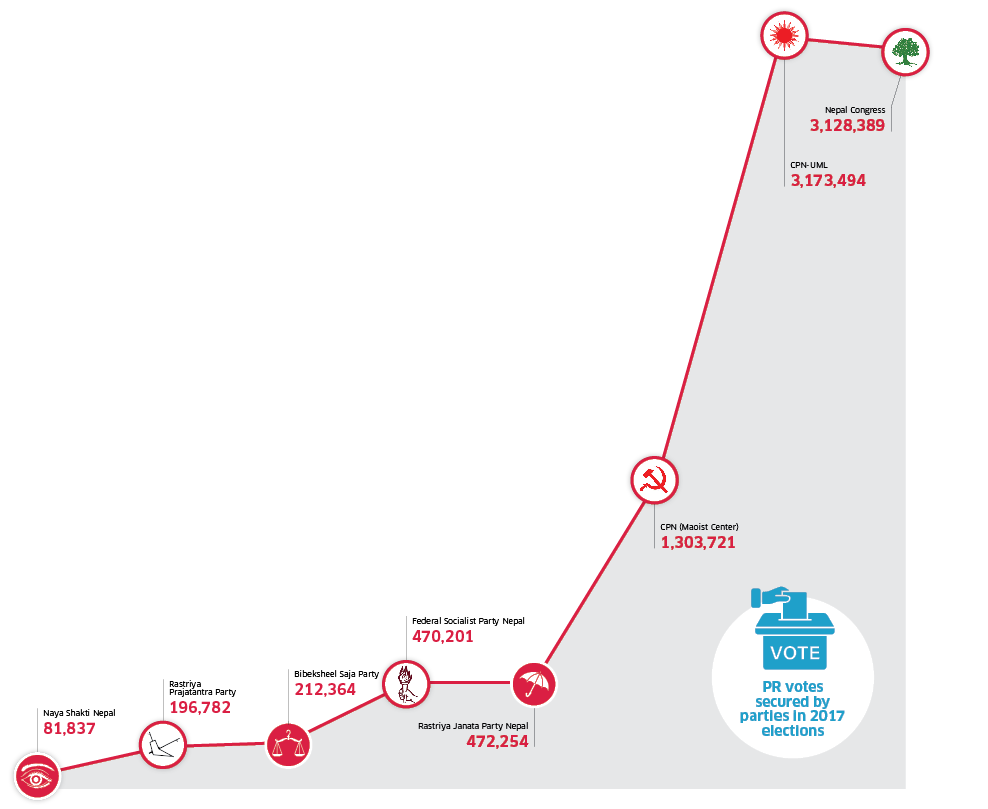

Infographic

PR votes secured by parties in 2017 elections

Nepal Congress: 3,128,389

CPN-UML: 3,173,494

CPN (Maoist Center) : 1,303,721

Rastriya Janata Party Nepal: 472,254

Federal Socialist Party Nepal: 470,201

Bibeksheel Saja Party: 212,364

Rastriya Prajatantra Party: 196,782

Naya Shakti Nepal: 81,837

Source: Election Commission

Deuba’s India visit: Symbolism over substance

Right or wrong, it is routine business for a Nepali prime minister to make New Delhi his first foreign port of call. And so on cue Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba is visiting India from April 1-3. Covid lockdowns notwithstanding, when Deuba became PM last July, there was no enthusiasm in New Delhi to roll out a red carpet for the septuagenarian Nepali leader. Things have not changed much.

Deuba is thus unlikely to sign any important agreement. Foreign policy analyst Geja Sharma Wagle says it is more a goodwill visit to strengthen relations at the top political level (see Editorial).

The visit coincides with some vital domestic, regional, and international developments. Deuba is visiting India ahead of local polls which will soon be followed by national elections.

As India is concerned over the shape of the post-election government, say Nepali Congress leaders, the issue could figure in bilateral talks. Of late, India has adopted a hands-off approach in Nepal but it has also subtly let its distaste for a broad (Panda-hugging) left alliance be known.

With India also closely monitoring the growing US-China competition in the Himalayas, the Indian side could convey to PM Deuba some message in this regard.

Says India-Nepal relations expert and ApEx columnist Nihar R. Nayak, India is uncomfortable with the growing strategic competition between two major world powers in the Himalayas. India expects these powers to respect India’s security concerns, he says, adding that this issue could crop up during Deuba’s Delhi trip. “India is worried that some Chinese projects in Nepal may undercut its strategic and security interests in the Himalayas. It does not want any disturbance on its northern frontier,” Nayak says.

The Russia-Ukraine crisis could also come up during discussions.

On the bilateral front, government officials say that even with low expectations, all outstanding issues will be discussed. Supply of fertilizers, connectivity projects mainly railways, Pancheshwar multipurpose development project are all on the agenda. Nepal is also preparing to raise the map dispute.

The aftereffects of Wang Yi’s Nepal visit

Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s three-day Nepal visit (March 25-27) was focused more on safeguarding China’s larger geopolitical interests than on bilateral cooperation. The readouts issued by the Chinese side during his stay as well as subsequent Chinese media reports suggest the same.

Securing the support of the South Asian countries on China’s position on the Russia-Ukraine crisis, countering America’s influence in the Himalayan region and creating a favorable political environment in Kathmandu were his key agendas. In his meetings with Nepali leaders, Wang pushed for Nepal’s ‘independent foreign policy’ and urged the country to stay away from geopolitical games—thereby becoming ‘a shining example’ of China-South Asia cooperation.

Speaking with Chinese media outlets in Beijing on March 28, the senior Chinese diplomat said there has been a general consensus among relevant countries that Russia-Ukraine disputes should be settled peacefully through dialogue, and neither war nor sanctions are the solution.

The US too is seeking the support of South Asian countries for its Russia-targeted sanctions. In Beijing, Wang said his trip to South Asia came at a time when the spillover of the Ukraine crisis is spreading, and world peace and development are facing new challenges. “Asia refuses to become a chessboard in the game between major powers, and Asian countries are by no means pawns in the confrontation between major powers,” Wang said.

Beijing is urging small South Asian countries not to be influenced by America on Ukraine.

Says Amish Raj Mulmi, the author of All Roads Lead North: Nepal's Turn to China, after the onset of the Ukraine crisis, China has been trying to build a new pro-Beijing consensus in South Asia.

China, through various channels, has already conveyed its reservations over Nepal’s decision to vote against the Russian invasion at the United Nations.

Even though there is no direct mention of America in Chinese official statements, growing American influence in Nepal figured high in talks at various levels between Wang and Nepali leaders.

In his meeting with CPN (Maoist Center) Chairman Pushpa Kamal Dahal, Wang said: “We should be vigilant against the resurgence of the Cold War mentality and chaos in the region and jointly safeguard the good situation of regional peace, stability and development.”

“It is necessary to maintain the hard-won peace, stability and development in the region, resist the temptation to introduce bloc confrontation and create turbulence and tension in Asia,” he added.

According to Maoist leaders, Wang also reminded Dahal of American attempts to encircle China through its Indo-Pacific Strategy (IPS) and that Nepal risked becoming a pawn in a great-power confrontation.

Chinese experts have also tried to explain Wang’s message to South Asian countries.

In his March 27 Global Times article, Zhao Gancheng, director of the Center for Asia-Pacific Studies at the Shanghai Institute for International Studies, says the US has somewhat achieved its goal of turning some of China’s neighbors against it without investing too many resources.

“This has encouraged Washington, making it believe it can contend with Beijing. Therefore, the US will mobilize more resources and be more active in an attempt to infiltrate what it sees as China's ‘sphere of influence’,” the article says.

In Kathmandu, Wang focused his message on mitigating growing American influence after the parliamentary endorsement of the MCC Nepal compact. Additionally, he sought strong commitment from the Nepali side on the “One China” policy.

All top politicians, including Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba and President Bidya Devi Bhandari, tried to assure Wang that Nepal is committed to One-China, and will not allow anti-Chinese activities on its soil.

US-based foreign policy expert Sanjaya Upadhayay says Wang sought to impress upon Nepali leaders “the imperative of creating the necessary domestic conditions” that would discourage Nepal from becoming a geopolitical playground against China.

He believes Wang was interested primarily in gauging Nepal’s continued commitment to its traditional foreign policy tenets amid shifting global geostrategic contours.

“In particular, Beijing sought to determine whether Kathmandu was adjusting its outlook and—if so—whether it was doing so under unwarranted influence of third countries,” Upadhayay says. As the Nepali side stated its case, he adds, Beijing must have sought fresh assurances from Kathmandu on One-China and other specific issues of Chinese concern.

To achieve those objectives, Beijing wants a favorable internal political situation in Kathmandu. Over the past few months, the relationship between Nepali Congress-led government and Beijing has deteriorated considerably.

Beijing thinks Congress is pro-India and by extension pro-US. The ruling party, meanwhile, is suspicious of Beijing’s “proactive measures” to bring left forces together.

In his meetings with Nepali leaders, Wang conveyed that China was ready to work with all parties, irrespective of their agendas and persuasions. Unlike in the past, the Chinese side did not explicitly raise the issue of left alliance this time.

Binoj Basnyat, strategic affairs analyst, suspects that with Nepal headed into elections, the Chinese are also concerned about the type of government that will be formed at the center and whether that government would favor them. “The political message of Wang’s visit is that unity among communist forces would be beneficial to Beijing. If that doesn’t happen, Beijing at least wants to create a favorable environment for it here.”

Basnyat is of the view that China wants to limit the activities of international forces in Asia.

Mulmi says Wang’s Nepal visit can be seen both as China attempting to build on its influence in smaller South Asian countries, as well as to negate its setback after the MCC compact ratification.

The visit clearly showed that Kathmandu risks becoming an epicenter of US-China rivalry in South Asia.In this fluid situation, Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba is traveling to India and senior American officials are soon visiting Kathmandu. Expect more turbulence in Nepal’s geopolitical weather-system.

Local level functioning: Glass half full

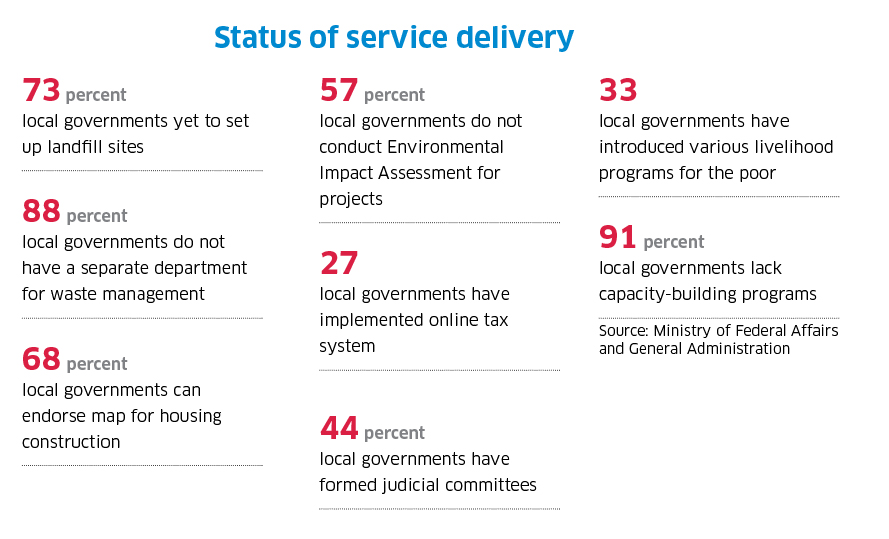

The 2015 constitution envisions local governments providing a range of affordable and timely public services. Responsibilities previously under the ambit of district administration offices or central agencies in Kathmandu are now handled by local units.

But as the sub-national bodies under the new federal setup complete their first five-year term, their performance has been mixed: some have done well while others are struggling.

According to a recent survey by the Commission for the Investigation of Abuse of Authority (CIAA), 67.3 percent of the respondents were satisfied with the services provided by their local governments. Only 11.2 percent expressed their dissatisfaction while 21.5 percent were neither satisfied nor dissatisfied.

The survey also suggests municipalities are performing better than rural municipalities, as the former are considerably better equipped both in terms of manpower and resources.

Federal affairs experts say as the first elected local governments under the new constitution, their five years were largely spent in infrastructure-building and capacity-enhancement. Their works, experts add, have laid a good foundation for the future.

Despite challenges, some subnational bodies still managed to do well.

The Municipal Association of Nepal ranked Waling and Putalibazar municipalities of Syangja district as the top performing local units in terms of service delivery and fiscal governance. Nilkantha Municipality of Dhading, Ilam Municipality of Ilam, Harion Municipality of Sarlahi, Tilottama Municipality of Rupandehi and Rapti Municipality of Chitwan were also on the association’s top municipality list.

Waling was recognized for its outstanding performance in service delivery through digital governance.

“In our municipality, people can access and pay for all services online,” says Mayor Dilip Pratap Khand.

Waling is also the first municipality in the country to pass laws and regulations required to implement the 22 exclusive rights the constitution provides to local governments.

To maintain transparency, the municipality discloses information about its services, activities, as well as incomes and expenditures. It has also developed a system to collect feedback on service delivery.

“We remove lapses in service delivery on the basis of the feedback we get from cross-party committees,” says Khand.

Some local governments like Bhaktapur Municipality proved their mettle during the pandemic. The municipal government, led by the mayor from Nepal Majdoor Kisan Party, provided door-to-door health services including PRC tests and built well-equipped quarantine centers in response to the pandemic.

In the past five years, judicial committees, led by deputy heads of local units, have also been instrumental in providing quasi-judicial services to the people. They are authorized to settle disputes in 13 specific areas, including those related to property boundary, canals, dams, road encroachment, wages, and lost and found cattle.

Most disputes settled by judicial committees have not been challenged in court—and that says a lot about their effectiveness.

But not all local governments have formed judicial committees owing to a lack of manpower trained in legal issues. Only 40 percent of local units have such committees.

Education is one vital area where progress in the past five years has been poor. Experts attribute this to the federal government’s reluctance to decentralize education as well as lack of local education laws, teachers and budget.

Still, some local bodies have set sterling examples by offering free school education.

Pyuthan Municipality of Pyuthan district provides free education up to the tenth grade. Its mayor, Arjun Kumar Kakshapati, says no children should be denied this basic right.

“Now all the children in the municipality go to school. We want the federal government to help us sustain our education campaign,” says Kakshapati.

Bhaktapur Municipality has also taken some notable steps in education, such as providing education loans and research funds.

Pyuthan and Bhaktapur are the outlier municipalities in education. Most local units are struggling due to inadequate resources and poor support from the central government.

According to the Ministry of Federal Affairs and General Administration, 87 percent of the local governments don’t have enough teachers.

Federal affairs expert Khim Lal Devkota says despite many challenges, there have been some positive changes in the state of education at the local level.

“Take the dropout rate,” he says. “The rate has come down thanks to initiatives like scholarships for children from marginalized communities.”

Besides education, local governments have also not made desired progress in health. Most of them still lack decent health facilities.

In the past five years, just 11 percent of local units built 15-bed hospitals, as required by the constitution. Government data shows that about 54 percent local governments are in the process of constructing such hospitals.

But even when hospitals have been built, they have lacked many basic health services. Lab services are generally poor and qualified and specialized doctors are in severe shortage.

Overall, some experts say while there is still a long way to go for the federal system to work smoothly, local governments have achieved significant progress in their first term.

Khemraj Nepal, a former government secretary, says local governments were concerned about the rights and plights of the marginalized groups, an issue that the central government largely ignored.

“Some local units in the Tarai have launched campaigns focused on the education of girls and children from marginalized groups,” says Nepal. “For instance these children are given bicycles to motivate them to go to school. These local bodies have also done a lot for senior citizens,” Nepal says.

His major gripe with local governments is with their manifest failure in stopping skilled manpower from migrating abroad.

Most local governments say inadequate infrastructure and resources mar their performance. They are short of human resources, including chief administrative officers, badly affecting service delivery. Dearth of staff means people are deprived of even basic services such as registration of life events, social security benefits, and recommendations for passports and citizenships.

Political disputes have also contributed to poor service delivery and dysfunction.

Over the past five years, dozens of local governments failed—some repeatedly—to bring their budget on time due to chronic disputes between municipal chiefs and their deputies. As many as 13 municipalities are yet to pass their budget for the current fiscal year.

According to a new study commissioned by the Ministry of General Administration and Federal Affairs, of the 753 local units, more than 200 have been operating under acting chief administrative officers. Works of these local units could be severely affected if these officers are transferred.

While local governments have taken the initiative to provide services, they have failed to make service delivery effective, says the study.

The ministry has recommended that the local governments invest in capacity-building and human resources.

Experts on federal affairs are optimistic that the performance of local bodies will improve.

“I’m happy with the overall performance of local governments in the past five years. Now we must focus on addressing the lapses in service delivery,” says Devkota.

What kind of financial help are we getting from China?

Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi arrives in Kathmandu on March 25 on a three-day visit, with project-selection under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) among his top agendas.

But with the Nepali side unprepared, the visit, however, is unlikely to be fruitful on the BRI front. Discussions are underway to forge an understanding for its implementation. But even such an understanding does not guarantee selection and implementation of specific projects.

A senior foreign ministry official requesting anonymity told ApEx that the ball is in Nepal’s court.

“First, we have to identify the projects. Then we have to conduct feasibility studies and prepare detailed project reports (DPRs) before proposing them to China. If the Chinese side agrees to our proposals, negotiations on investment modality can begin,” says the official who is also involved in bilateral negotiations.

On each of the nine projects Nepal has shortlisted under the BRI, it has to negotiate loans with Chinese banks—not the Chinese government. (But the Chinese government can instruct those banks to offer loans on lower interests or even, in rare cases, interest-free.)

“There is a misconception here, even among our top politicians, that once we make a list of projects, the Chinese will do the rest. That is not so,” says the official.

According to him, the BRI is a broad program, but in Nepal, it is often—and wrongly—thought of as synonymous with specific development projects.

In the past five years since the signing of the BRI framework, negotiations between the two sides have focused on preparing legal documents. The only other achievement in this period was the inclusion of Nepal-China Trans-Himalayan Multi-Dimensional Connectivity Network, including a cross-border railway, in the joint communique of the second BRI conference in 2019.

“So far, we have focused on the blueprint and legal documents. We are yet to enter real negotiations on specific projects,” says the official.

The BRI is basically about taking loans from Chinese banks to build infrastructure. But Nepali leaders who are in conversation with Chinese leaders have been emphasizing grants for the BRI projects. For instance, in 2018, the KP Sharma Oli-led government negotiated with the Chinese on the Keyrung-Kathmandu railway. The Oli government reportedly told the Chinese side to provide a grant for the railway project.

“China is not ready to build such a big project on grant-basis as it entails a big financial commitment,” says the government official.

Prakash Saran Mahat, former foreign minister who signed the BRI framework, says Nepal plans to mainly improve road connectivity with the Chinese money.

“We cannot afford projects under commercial loans. We should thus emphasize grants and soft loans,” he says.

There was no discussion on investment modality when the framework agreement was signed. However, global trends suggest grants under the BRI projects are hard to come by.

“You have to keep in mind that the BRI projects in Africa, Latin America and Southeast Asia were built with loans from the Exim Bank of China, the China Development Bank, and other Chinese banks,” says the government official.

According to a report prepared by AidData, an international research and innovation lab, China Eximbank and China Development Bank led a major expansion in overseas lending in the pre-BRI era.

“However, the country’s state-owned commercial banks—including Bank of China, the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, and China Construction Bank—have played an increasingly important role during the BRI era. Their overseas lending activities increased five-fold during the first five years of BRI implementation,” says the report.

The specifics of such deals are hard to find in the public domain. But government officials say loans under the BRI should not be frowned upon as we need all the money we can get to build big infrastructures and spur economic growth. In any case, they say, Nepal is already taking loans from other international financial institutions.

“In the past, many multinational financial institutions snubbed our request for infrastructure loans. So we can use Chinese loans to build desired projects if we get the right rate,” says the official.

For instance, Nepal has built Pokhara International Airport with a Chinese loan at two percent interest.

Officials say multinational financial institutions like the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank work in ways that are distinct from how the Chinese operate. These institutions themselves conduct feasibility studies and prepare DPR for a proposed project, and they offer loans only if they find the project feasible. On BRI projects, however, all these tasks are undertaken by the loan-recipient countries.

Over the past decade, China’s policy on loans has undergone a sea-change. Initially, they provided loans without considering the pay-back capacities of recipient countries. As a result, many countries could not pay back, resulting in what has often been portrayed in Western media as ‘debt-trap’.

Government officials say China has learned its lesson and is now more cautious while providing loans under the BRI projects.

“Unlike in the past, the Chinese are not pressing poor countries like Nepal to take loans for development projects. They are also asking us to consider our pay-back capacity and come up with feasible projects,” says the government official.

Chinese loans constitute only three percent of Nepal’s total foreign loan portfolio. The Ministry of Finance seems reluctant to take out a loan under the BRI, owing to its high interest rates. This is one reason for the BRI’s slow progress in Nepal.

To move ahead, it is vital that political leadership offer policy-guidance to the bureaucracy.

China is already providing large grants to Nepal. Officials say it is obvious to expect more grants from China, but it is better to ask for bilateral grants instead of grants under the BRI.

Suresh Chalise, a former Nepali ambassador to the US, says it is illogical to ask for a BRI grant just because we have gotten a grant under the Millennium Challenge Corporation compact. “China is already giving us other grants,” he says.

But Kalyan Raj Sharma, a China expert, does not rule out the possibility of BRI grants. “There are many ways the two countries can cooperate financially under the BRI,” he says.

China offers three categories of assistance to other countries—grants, interest-free loans, and concessional loans. It has also canceled debts of some hard-pressed countries.

According to a 2019 World Bank report, most Chinese loans are concessional, but with terms that may not be favorable for low income developing countries (LIDCs). Most Chinese loans to LIDCs have fixed interest rates, with a median rate of two percent, a grace period of six years, and a maturity of 20 years, according to the report.

Da Hsuan Feng of the Center for Asian Studies at the University of Texas at Dallas, says China wants prosperity for its neighbors, even the poor ones, through the BRI vehicle.

He says the 10 ASEAN nations, especially poorer ones like Cambodia and Laos, are showing signs of economic vitality thanks to the BRI.

“Under the BRI, China and Laos collaborated in constructing 1,000km high-speed rail from China’s Kunming to Laos’ Vientiane,” he says. “Clearly, by itself, Laos could not and would not have the financial and technological means to build this vital rail-line.”

The new railway could transform the future of this landlocked country, he says.

He says leveraging the BRI to collaborate with Nepal must be a high priority for China, just like collaborating with Laos is a high priority. “A prosperous Nepal will be a tremendous plus for China in the same way that a prosperous Laos is a plus for it,” he says.