How South Asian states are managing Chinese influence

A day after the devastating earthquake in Nepal in April 2015, China dispatched a 68-member search-and-rescue team to aid its southern neighbor. Within months, it had pledged over $650 million to help Nepal. The event also acted as a springboard for several long-term Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief initiatives, such as an MoU on risk reduction and emergency response signed during President Xi Jinping’s visit to the country in 2019.

Nepal is not alone. Over the past one decade, moves like these have indicated a deepening engagement between China and countries in South Asia such as Bangladesh, Maldives, and Sri Lanka. In fact, China’s economic and political footprint has expanded so quickly that many countries, even those with relatively strong state and civil society institutions, have struggled to grapple with the implications. This reflects in China involving itself in domestic political developments in these countries, actively pursuing people-to-people relations, and even influencing how it is portrayed in the media in these countries.Our project, “China’s Impact on Strategic Regions,” is aimed at understanding the effect of such engagement and is based on a sharing of experiences across national boundaries by dozens of influencers with deep local knowledge. The study found that Chinese engagement leaves a deep impact on the institutions, civil societies, and elites of partner countries. The effect is higher in aspects of state and society that are already under duress.

A critical understanding of the drivers of this engagement, the various forms it has taken, and its impact on South Asian countries has been largely missing from the discourse, which is punctuated by broad-based assumptions such as allegations of debt-trap diplomacy. In reality, however, in a multidimensional region like South Asia, each of these relationships—in Bangladesh, Maldives, Nepal, and Sri Lanka—are unique. In Nepal, while centuries-old ties of trade, culture, and family were the initial drivers, in recent years China has had other avenues to expand its influence. At present, development assistance and Nepal’s keenness to explore an alternate route for trade and transit have taken the center-stage in the relationship with China.

Also read: US engagement in Nepal to grow, with or without MCC

However, this has also meant that for every instance of successful partnership, as in the case of the Pokhara International Airport, there is an instance of shrinking space for Tibetan issues in Nepal’s newspapers; or for every instance of a fiber-optic cable link with China ending Nepal’s dependence on internet through India, there is an instance of Nepal’s state-owned airline finding aircraft purchased from China unprofitable and unviable.

Significantly, we found that contrary to popular discourse, partner countries such as Nepal wield considerable agency, learning from their experiences and that of others in the region. This is reflected in the rigor to evaluate all available options before accepting Chinese proposals, and, if need be, reject them, as in the case of the Budhi Gandaki Hydropower Project, which was found irregular and non-transparent by a parliamentary committee in 2017.

For all their uniqueness, as developing states, the common and overwhelming motivation for the countries under study is the quest to partner with countries that can help develop their economy, improve their infrastructure, and help their citizens meet their ambitions of a higher standard of living. These countries will engage the United States, China, or anyone else that can best assist them in realizing these goals.

In this scenario, the challenge for the US and its partners is to develop a policy that consistently and productively engages South Asian countries on their developmental needs. It follows that such engagement should be based on its own merits, delinked from how the countries choose to engage with China.

The decision at the Quad summit in March 2021 to focus on vaccines, emerging technologies, and climate is a productive step in this direction, as is the Build Back Better World initiative, announced at the June 2021 meeting of G7 leaders. Together with the Blue Dot Network, it has the potential to offer the kind of engagement these states seek.

As countries in South Asia graduate to lower middle-income status, they are likely to require assistance in dealing with a new reality where they are ineligible for much of concessional financing. The United States could use its influence in Western multilateral organizations to ease the transition and help these states develop the capacity to access alternative avenues for assistance.

Beyond state institutions, there is scope for partnership with other organizations. Media outlets and civil society organizations in all four countries have been focusing on questions of good governance—from their regimes’ human rights records to opacity in Chinese contracting practices. Building their capacity, over time, will lead more stakeholders in these countries to see the dangers of opaque deals and ignoring environmental and other concerns.

This new report has been translated in Nepali, Bangla, and Sinhala with the hope that it helps generate reasoned discussion in these places beyond just the elites—considering Chinese engagement is increasingly a whole-society phenomenon.

Pal is a visiting fellow in the Asia Program at Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. He tweets @DeepPal_. Chadha is a research assistant and project coordinator in the Asia Program at Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. He tweets @SahebSChadha

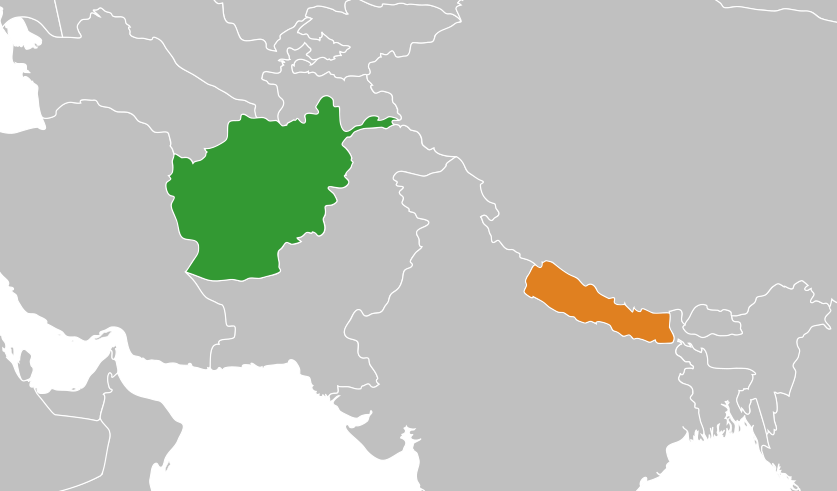

Opinion | Dealing with new Afghanistan, a Nepali perspective

Sooner or later Nepal has to come to a working relationship with the Taliban-led Afghanistan. There are more factors linking these two countries than those dividing them. Both are landlocked. Both are members of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), the UN, and the IMF. Both have joined the China-led Belt and Road Initiatives, and are observer members of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. Both nations are trying to come out of messy conflicts, discard the ‘least developed’ label and achieve ‘developing’ status.

Politically, Nepal has embraced a socialism-oriented, secular multiparty democracy. As a signatory to a series of human rights treaties, and as a UN member, Nepal is bound to promote universal respect for and observance of, human rights and fundamental freedoms of all without distinction as to the race, sex, language or religion.

The new Taliban regime of Afghanistan has said the country will be ruled under the Islamic sharia law. Nepal maintains a friendly relation with Afghanistan, and is unlikely to bother with its internal affairs. We should indeed respect the religious, political and economic choices of Afghan people.

In the broader spectrum, Nepal is itself a country sandwiched between two giants with different political and economic systems. It needs to use its limited strength and influence prudently. Protecting national sovereignty, safeguarding interests of Nepali nationals, providing reasonable support to Nepali blood, languages, cultures, identity and history, both inside and outside the current political borders, are our primary duties. Afghan people and big powers among them will solve the issues of human rights, counter-terrorism, and other conflicts associated with values there.

In terms of political maps, sometimes united and sometimes divided, Nepal has remained an independent, sovereign country. Even if outsiders have settled in Nepal and ruled it, they have ultimately been assimilated to the Nepali soil, their off-springs becoming dhartiputra or the children of the land. A key to our success was articulated by our founding father Prithvi Narayan Shah who suggested Nepal maintain good relations with China and India.

The land of present-day Afghanistan has been invaded and ruled by different forces in history. It was conquered by Darius I of Babylonia circa 500 BC, Alexander the Great of Macedonia in 329 BC, Mahmud of Ghazni in the 11th century, and Genghis Khan in the 13th century. Even after Afghanistan was created as a nation in 1747 by Ahmad Shah Durrani, through a series of wars in the 19th century, it was forced to cede much of its territory and autonomy to Britain. Afghanistan gained full independence from British influence only in 1919.

Following the British withdrawal from India in 1947, Afghanistan had to handle a largely uncontrollable border with the newly-formed Pakistan. Afghanistan and the Soviet Union became close allies in 1956, followed by Afghan reforms the next year, allowing women to attend university and join the workforce.

Conflicts and internal fights led to the 1979 Soviet invasion and the 1989 withdrawal; the 2001 US invasion and the 2021 withdrawal. Located at the strategic crossroads of Central Asia, South Asia and West Asia, Afghanistan has been a battleground of different political, religious, cultural and economic powers throughout history. So far all attempts to occupy Afghanistan have ultimately failed.

The effects of the American counter-terrorism campaign since 9/11 have not been uniform. In countries such as Saudi Arabia, UAE and Qatar where the US did not seek regime change, the US efforts have been a success. In countries such as Syria, Iran, Afghanistan and Iraq where the US focused on regime changes, the US efforts have failed to contain.

The terrorists have succeeded in identifying themselves as the forces fighting the US and other anti-Islam countries and forces, and thus winning Muslim sympathy worldwide. Besides, the hidden American geopolitical interests helped blur the differences between moderate Muslims and hardliners, many a time tagging moderates as hardliners, which ultimately led to the spread of terrorism.

Also read: China-South Asia cooperation: Sky’s the limit

Americans first tried to use the Islam element to counter the Soviets. After the downfall of the Soviet Union, this trained militia turned on the US, their former mentors. As such, it is not a confrontation between two civilizations; it is not a West-versus-Muslims clash. It is a confrontation between two interest groups to dominate the world, the resources. The US being the stronger one adopted the role of the ‘world police’. The Muslim outfits being the weaker side tried to present themselves as ‘Muslim fighters’ to challenge the US, in the form of modern guerrilla attacks.

Following the US withdrawal, the world is divided on tackling Afghanistan. The US and its allies have refused to formally recognize the Taliban-led government. But China, Russia, Pakistan and some others have maintained relations with the new regime, some hoping the Taliban will help counter cross-border terrorism, contain radical Islamist ISIS group and respect the rights of women and minorities.

What should Nepal do?

Nepali people and media seem divided on the Afghan issue. Some have expressed worries that extremists have come to power; others are happy that the US occupation has ended. This scribe would rather recommend a careful, weighted response.

Nepal has an open border with India. Unlike China and the US, we are unable to control the border effectively. Not far back, Rohingya refugees from Burma, some Afghan refugees, and even Congolese refugees, have successfully made their way to Kathmandu. So tightening of the land border, especially in cooperation with India, should be our top priority. Similarly, we should beef up scrutiny against suspicious international arrivals by air.

As to maintaining our relation with the Afghan regime, we should raise issues of our interest. It was the Taliban that demolished the two monumental fifth century Buddha statues in Afghanistan's Bamiyan Valley in 2001. The fanatics did not pay any heed to the worldwide condemnation of their cultural crime. Buddha is a part of our history, our identity and Nepal is the mother of Hinduism, Buddhism and related language and culture. We should talk about these issues openly. Our foreign policy should reflect our interests in a broader sense.

Opinion | Nepal’s COP26 commitments

Greta Thunberg, the student activist who galvanized a global movement that is challenging world leaders to do more on climate change, summarized the UN climate conference held in Glasgow over the first weeks of November as “blah blah blah.”

But if any country could have made her proud, it would have been Nepal.

In a statement at the conference, Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba, who also led Nepal’s delegation to the summit, made three bold commitments.

First, he noted that “Nepal aims to reach a net zero emissions by 2045.” This would mean that by 2045, Nepal would not emit more greenhouse gas than it saved (i.e., net zero). Second, he committed that 15 percent of our total energy demand would be supplied from clean energy sources. Third, he committed to “maintain 45 percent of our country under forest cover by 2030.”

Some of these commitments are, however, conditional on Nepal securing adequate climate financing.

The prime minister’s commitments went beyond what Nepal had previously outlined in its second submission of National Determined Contributions to the UN last December.

His commitments got a mixed reaction. Donors and development partners welcomed it as pathbreaking. Nepali professionals who work in the sector welcomed it cautiously, pointing out that the true test would be in implementation. For the broader Nepali public, there were other things to worry about—the state of the judiciary, for example.

The commitments were surprising. Maybe not to those who helped write the PM’s speech. But for many, it was a stunning announcement—one that defied expectations and invited cynicism.

The surprising—though bold—announcement raises an important question of how much ownership the country really has of its plan. Over the past few years, there has been an effort to broaden Nepal’s climate discourse to a wider range of stakeholders. But it hasn’t gone far enough.

Plans and bold announcements—the prime minister’s commitments being a recent good example—often represent the narrow views shared only by those who write the speeches. The reason that implementation of the plans then fail isn’t always because Nepal lacks the capacity or the finance. Rather it is because those tasked with implementing the plan have never even heard of it.

Whether PM Deuba’s climate commitments were backed by consensus and planning at home or represented two minutes of glory on the international stage, is perhaps irrelevant.

Nepal needs big, bold, and immediate action on climate. As the prime minister noted in his speech, “around 80 percent of Nepal’s population is at risk from natural and climate-induced hazards. During the last 40 years, natural disasters have caused close to US$ 6 billion physical and economic damages in my country alone.”

And that estimate is probably a gross under-count. With a fragile geology, vulnerable population, and an economy highly dependent on weather, Nepal is at the frontlines of climate change with much to lose.

Also read: Opinion | Nepal’s electric addiction

For Nepal, investments on climate mitigation and adaptation are ideal to build the basis of economic growth, reduce poverty and enhance resilience. Nepal’s recent submission on nationally determined contributions and the prime minister’s speech at Glasgow both highlighted its intent on instituting approaches that leave no one behind.

Nepal’s policies must align with that goal and its commitments. Many of its current policies disproportionately favor the rich and exacerbate climate vulnerabilities of the poor.

On energy, for example, Nepal has committed to ensuring that 5-10 percent of its power generation capacity comes from mini- and micro-hydro power, solar, wind and bio-energy renewable energy plants (where renewable energy is defined as less than 1 MW). However, Nepal’s energy policies are marginalizing such plants. Hundreds of small such plants are decaying and being left to die as supply from large hydro-plants grows.

On transport, which is another important source of fossil fuel use and energy imports, the government has announced ambitious plans to promote electric vehicle use. But a wrong mix of tax incentives is enabling the rich to adopt electric vehicles while distracting from the need to invest in electric public transport and accessible individual transport for the poor (such as electric bicycles).

The prime minister’s COP26 commitments on climate should be welcomed. But Nepal must also ensure that its policies and investments equally serve the poor and offers a base for stronger, inclusive and resilient economic growth.

Opinion | Dangerous morning walks

I am a seasonal fitness freak. Most of my exercise regime starts after the grand celebrations of Dashain and Tihar. The endless marathon of eating and drinking is a nightmare for anyone who lives in this part of the world of dress size. I do make a conscious effort to control the intake but as this time is heaven for foodies like me, a little of this and a little of that is enough to put on some extra pounds after these festivals.

So this year my elder sister and I decided to start early on our fitness agenda. We still believe that the pandemic is not over yet and sharing a covered gym hall with strangers coming from different environments can be catastrophic to our family’s health. So, the option that we agreed on was to go for walks. Since we don’t have precise working hours, we opted to wake up an hour early.

I am a grumpy cat when I work out. I don’t prefer to talk much or interact. Well, you got to understand, speaking itself is an exercise and that also you do on top of walking—it is double exercise and I don't like to exhaust myself. So I observe people; I observe attitudes; I observe stories.

On and off, I have been walking for years. But the kind of people I see hasn’t changed much. For all apparent reasons, it is mostly those who are fluffy (I hate to call them fat or obese). I hardly see any “fit” people running or walking in the mornings. Fit in an athletic and Body Mass Index (BMI) sense. I guess that population is to be found in fitness centers and clubs. A lot of times I hear people say they want to lose some weight and only then move to a gym. The gym environment is extremely competitive and people who are starting or have weight issues feel inferior and out of place. It definitely takes a lot of dedication and endurance for fluffy people to last in the gyms.

Anyway, when I talk about people I meet during the walks, one important group is those who are in dire need of weight-loss. Mostly, women in their mid-30s to 50s and clusters of two or three walk the same route because a big vegetable market happens to fall on their route back home; or maybe they made their route convenient according to the vegetable/milk market.

The second category is men in the age group of 40-60 in 5-7 member clusters. Mostly living in the same colony or from the same tole, these people walk longer hours and their walks end in a park or a tea stall where the politics of Nepal is dissected every day.

Also read: Opinion | The world ain’t Squid Game

The final group consists of what I wish to call “The uncle gang”: men who are my dad’s age (70-80), nicely dressed in branded tracks and sneakers, most likely retired jolly good fellas. As they are retired and spend the whole day at home, coming out in the morning is probably a treat for them. There is one such group we meet almost every day, composed of three-four uncles who are extremely energetic and full of laughter. We often saw them going to a bhatti. One day we decided to observe them and were startled by their early-morning smoking, shots of local aila, followed by milk tea with sugar.

It might seem normal at first, but to think of it, this is pure naughty of these aged men. I am sure they all are barred from these activities and morning walk is a perfect excuse for them to earn some freedom. The whole time I was watching them, scared if they had a medical condition, that they are restricted from certain habits and lifestyle—how wrong I had been! I wonder if their families know. I understand 15-16-year-olds misbehaving for adrenaline but at 70 it seems pure negligence and stupidity.

Living on the edge doesn’t mean abusing life. It will be a heart-break if something bad happens to one of them and their family blame it on exercise or a disciplined lifestyle.

That day, I got home and asked my dad if he had done something similar while he was a morning-walk enthusiast. The times! Now we need to maintain surveillance on our parents, what they are eating and doing. Now we need to take up their responsibility.