Jessica Stern: Nepal a beacon of hope for South Asia’s LGBTIQA+ community

Appointed by President Joe Biden in June 2021, Jessica Stern is an US special envoy to advance the human rights of LGBTIQA+ persons. She specializes in gender, sexuality and human rights globally. Her role as a special envoy is to ensure that American diplomacy and foreign assistance promote and protect the human rights of the LGBTIQA+ community around the world. She recently visited Nepal and met several members of Queer community, government officials and other stakeholders. Kamal Dev Bhattarai of ApEx caught up with her. What is the purpose of your Nepal visit? One of my responsibilities is to identify the countries that have best practices on people belonging to this community. There is not a country on the planet that does not discriminate against this community. The question is: How can we accelerate the pace of change, what policies and programs should governments invest in so that members of this community enjoy citizenship rights? Nepal has been at the vanguard in terms of recognition of this community in the constitution and seminal Supreme Court decision. Actually, the US can learn a lot from Nepal when it comes to the legal arrangements. I came to know how this community is living here. During my stay in Kathmandu, I talked with more than 50 members of this community, government officials and representatives of institutions working on Queer issues. What major concerns did members of this community share with you? I heard that transgender people still experience high-level of discrimination and violence and it is very difficult for them to change the citizenship document. And without access to legal documents that reflect your gender marker, it is tough to get a job, housing and other facilities. People of this community want access to equal marriage, they want to be able to adopt children and they want to be recognized as parents. How do you see the legislative status of Nepal with regard to queer rights? When I spoke with members of this community here, I came to know that they want a broader rape law because any person of any gender and sexual orientation can be a victim of rape. They want an easier pathway to citizenship recognition. People want equal marriage. They want to be entitled to full protection that every citizen is provided. And women want to pass citizenship to their children. That is the priority for the people here, not only for the heterosexual people but all women. When women are not seen as full citizens in the eyes of law, it has spillover effects at the community level. How do you compare Nepal’s status on queer people to other South Asian countries? Nepal is a beacon of hope in this region. LGBTIQA+ communities in other countries often say: We want to be more like Nepal, Nepal has received recognition from the court, they get meetings with the government and they are not criminalized. I think these are the markers of success in the region. Nepal is a symbol of hope on queer rights. The country is a leader in this region on human rights of these people. If there is further progress on LGBTIQA+ issues, it will not only be good for Nepal but also for entire South Asia. LGBTIQA+ communit y still faces discrimination in Nepal and many members are not ready to come out. What are your suggestions? A lot of people are still afraid to come out because of practical reasons. When you come out, there is a risk of family rejection. Many communities cannot live with their family because they are not accepted. I met those people who were homeless because it is difficult for them to find a landlord. Many of them are unemployed or underemployed. We should think about how everybody can support them. It is very simple: respect all people, love your children no matter who they are, do not reject them. Governments in all countries, including here in Nepal, need to ensure the most vulnerable get additional support. They should certainly get more resources.

Aditya Raj Budhiya: We deal in efficiency and experience

Rukmani Group has been importing luxury bathroom products in Nepal for the past 30 years. Most of its customers are upscale hotels and a handful of private individuals willing to spend on having a ritzy living experience at their homes. Anushka Nepal of ApEx talks to Aditya Raj Budhiya, the group’s executive director, to find out what sets apart Rukmani’s products from the rest and what is the company’s future. What are the luxury products that Rukmani Group imports? Rukmani Group mainly imports high-end bathroom products from tiles to fixtures. For example, we import tiles from Spain and Italy and bathroom items and accessories from internationally acclaimed brands like Armani and Axon. The reason why we associate our products with luxury is because they don’t just serve their basic purpose. The showerheads that we find in most homes and hotels in Kathmandu only serve one primary objective. But the ones we import, though expensive, have multiple functions. They have different water flow, bluetooth for the ones who love to shower with something playing in the background and light settings. We deal in efficiency and experience. What is the goal of your company? Our main focus has always been customer satisfaction. For the past 30 years, I can proudly say that we have dedicated ourselves to giving our customers what they need, rather than what we want them to buy from us. My father started this business as a way to introduce Nepal to many efficient household necessities. Three decades ago, Nepal had no access to such products. So one of our goals is to make these items available for anyone interested in having a luxurious experience at their homes, offices and businesses. How is the business faring after the Covid-19 pandemic? Covid hit our business like many others, but I think we have bounced back. We always have an emergency fund, which came in handy to cushion the blow dealt by the pandemic. Plus, we never let our loans cross a certain limit. These things helped us a lot to keep our finances stable even during the lockdowns that forced many businesses to close down. After the Covid restrictions were lifted, we did receive a lot of customers willing to spend money on luxury bathroom products. Perhaps, after spending months cooped up in their homes, they wanted to make their home living more comfortable. The resumption of international travel might also have helped because some customers wanted the products they saw in foreign countries installed at their homes. Who are the customers of Rukmani Group? Most of our customers are currently in the hospitality sector. We supply our products to hotels in Kathmandu that want their customers to have a comfortable experience during their stay. The hotels that demand these products fall slightly on the expensive side. We also have clients who buy our products for their homes, but their numbers are few. We don’t pretend that our products are affordable. It is understandable that most people would rather have a Rs 3,000 showerhead at their homes than a high-end Rs 300,000 one. Nevertheless, the number of people interested in our products for their homes is increasing, especially after Covid-19. What is your future plan for the company? Our main goal at Rukmani Group is to become a one-stop solution for those who are looking to invest in efficient interiors in their houses. From bathroom to kitchen to their bedrooms, we want to provide them with everything they want and need. Currently, we only deal in bathroom tiles, fixtures and accessories, but we are planning to expand towards home automation. We want our customers to have a highly efficient and secure living experience. We are talking about smart homes, where you can control everything with your smartphone, from wherever you are.

Zhiqun Zhu: Focus on development. Do not get involved in great power rivalry

US House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s recent Taiwan trip has greatly strained US-China relations. Beijing has called the visit “irresponsible and irrational” and suspended all engagements with Washington on military, climate change and other crucial issues. What’s next for these two competing powers and how will their future relations affect the world order? Kamal Dev Bhattarai of ApEx talks to Zhiqun Zhu, professor of political science and international relations as well as the inaugural director of the China Institute, at Bucknell University, US.

How did you see the US House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan?

It’s totally imprudent at a time US-China relations are in a terrible shape. She shrugged off repeated warnings from China and dismissed serious concerns from the Biden administration and many well-respected scholars and former government officials. She knew the risks associated with this trip, which is why she did not include Taiwan in her published itinerary and kept everyone guessing even after she had started the Asia trip. Despite the misgivings, she proceeded with the controversial visit. It was this irresponsible behavior that led to the current tensions in East Asia.

Has there of late been any shift in America’s ‘One China’ policy?

The core of America’s ‘One China’ policy concerns Taiwan’s status. It is based on the three PRC-US joint communiqués and the Taiwan Relations Act. The US acknowledges the Chinese position that Taiwan is part of China and only maintains unofficial relations with Taiwan. Recently, the US has added the Six Assurances—the Reagan administration’s principles on US-Taiwan relations—to its definition of ‘One China’.

Both the Trump and Biden administrations upgraded US-Taiwan relations, such as signing the Taiwan Travel Act into law and lifting restrictions on interactions between US and Taiwan officials. The US government has also publicly admitted to the presence of a few dozen US troops in Taiwan. One doubts whether Washington still strictly follows its ‘One China’ policy or has moved to ‘One China, One Taiwan’ policy.

How do you see the growing competition between the US and China in the Indo-Pacific region?

A rising tide lifts all boats. So a healthy competition is good. However, the US and China today are engaged in a zero-sum or even negative-sum competition in the Indo-Pacific.

China has become more assertive in foreign affairs as its power continues to grow. It is more willing to use hard power to deal with disputes with other nations. The US, meanwhile, has formed new or strengthened existing multilateral groups to counter China, such as AUKUS, QUAD, and Five Eyes.

The US is also promoting a free and open Indo-Pacific and has launched the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework, in which China is not included. This has raised concerns that the framework may be an anti-China group.

South Asian countries are feeling the heat of deepening US-China rivalry. What are your suggestions for smaller countries in the region?

When the two great powers are competing ruthlessly, there is not much small countries can do. The best strategy for small countries in South Asia and elsewhere is perhaps to focus on domestic development. Do not get involved in the great power rivalry.

And if some small countries prefer to be more vocal, perhaps they can learn from Singapore and tell the two great powers to not force them to choose sides, and resolve the differences peacefully.

What are the prospects of US-China relations?

The US will do its utmost to maintain global supremacy and will push back any challengers. China is marching towards realizing the ‘Chinese Dream’ of restoring its historical status as a wealthy and powerful nation. China may not be interested in replacing the US as the global power, but its rise is threatening America’s dominance. Given the structural conflicts, the prospects of US-China relations are not promising. The only way out of this dilemma is to face the reality, respect each other’s legitimate rights and focus on areas of common interests. The two great powers will have to learn to co-exist peacefully while working together to tackle global challenges such as climate change.

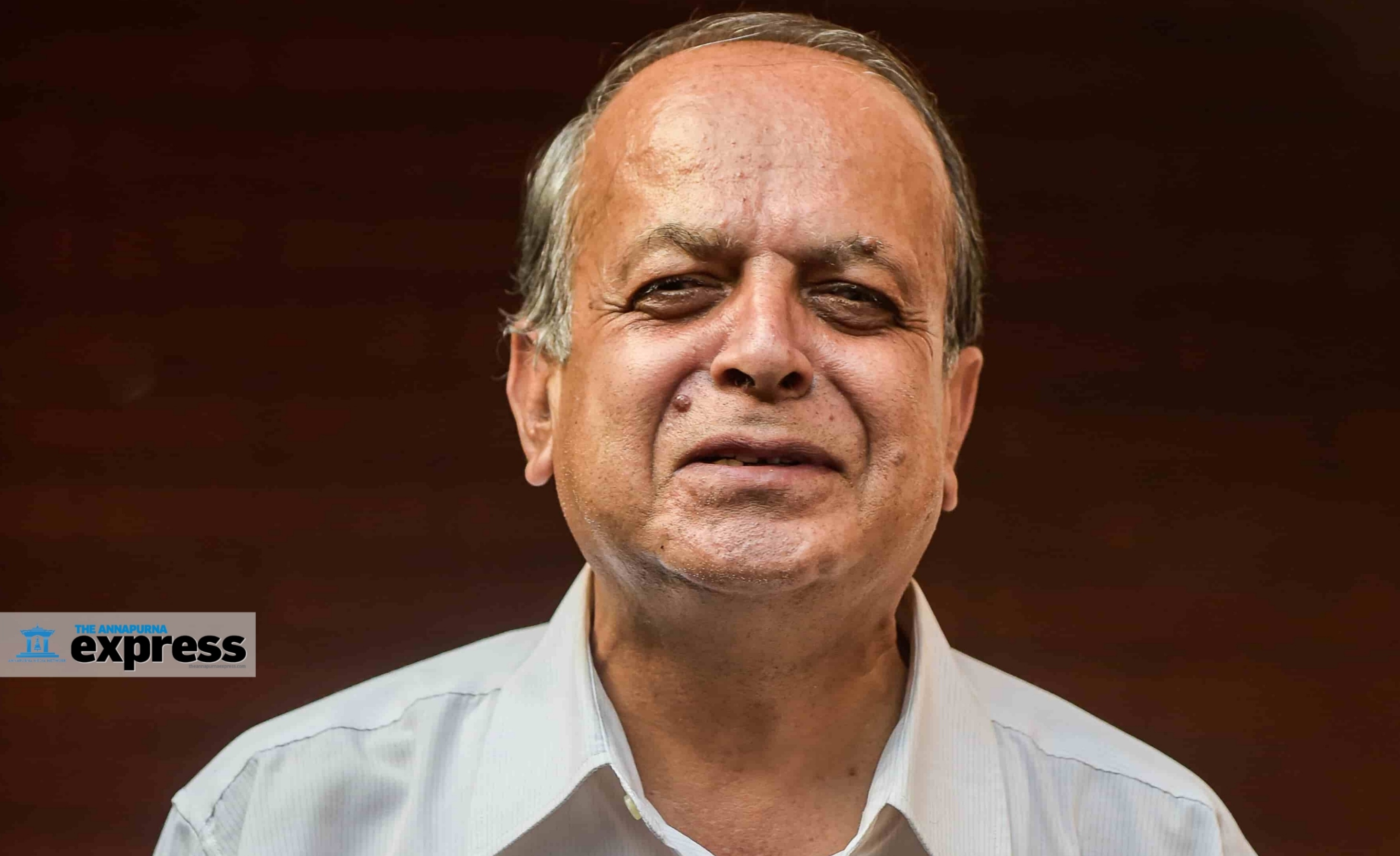

Mahendra P Lama: South Asia’s state institutions under China’s sway

Nepal-India relations hit an all-time low over a map row in 2019. Three years later, the two countries’ ties seem to be on the mend. Of late, India’s engagement with Nepal has been largely focused on development, economic and connectivity and it has uncharacteristically maintained a low-key approach. In this connection, Kamal Dev Bhattarai of ApEx talks to Mahendra P. Lama, an expert on India’s neighborhood policy and a member of the Indian half of the Nepal-India Eminent Persons Group (EPG).

How would you evaluate the current state of Nepal-India relations?

After a few years of stalemate, Nepal-India ties are looking up again. It had to at some point because the two countries have strong people-to-people relations. No matter what happens between Kathmandu and New Delhi at the political level, Nepali and Indian people living in border areas will continue to maintain their age-old relations.

Do you think Nepal-India connectivity is improving?

Connectivity remains one of India’s priorities, not just with Nepal but also with all its neighbors and beyond. For instance, there is India’s India-Myanmar-Thailand Trilateral Highway, which will be extended to Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam. So, India clearly prioritizes infrastructure.

As Nepal is already practicing federalism, the federal units should assert themselves on connectivity. It should not be Kathmandu’s issue alone. Province 1, for example, should think about how it wants to link up with Bangladesh. The provincial government should talk with the government of India about opening a corridor. Nepal’s provincial governments should also take the initiative to find out what India thinks about the connectivity projects.

There was an enduring perception that India interfered in Nepal’s internal politics. But India of late seems to have changed its approach. Do you agree?

I think more than India, it is Nepal that should change. If there is strong Nepal with strong leadership, India and its leaders will not interfere in Nepal’s affairs. Just look at India’s relations with Bangladesh and Sri Lanka. Where is the scope of interference? I think this issue can be resolved with strong Nepali leadership, institutions and policies. Every powerful country likes to manage and control a weak country. This is not just the case between India and Nepal. It is happening with China and its neighbors as well.

The report of the Eminent Persons Group (EPG) that you helped draft has not been submitted to the respective governments. Why?

I do not know why the report’s submission has been delayed. Apparently, Prime Minister Narendra Modi has not accepted it. And unless he does, the hands of Nepal’s prime minister are tied as well. The report offers new direction and vision for Nepal-India relations. If the governments of the two countries were to study it, they would see its benefits. It encompasses many issues on the future of Nepal-India relations.

How do you see China’s growing influence in South Asia including in Nepal?

China is not a new player in South Asia. It has been competing against India for regional ascendance since the 1970s. In that decade, China built many highways in Nepal as well. But development projects are nothing new. What is new, however, is China capturing the state institutions of South Asian countries. To a large extent, China is influencing the people who manage these institutions. Now people suddenly understand what is happening. Just look at Sri Lanka. The country’s parties and institutions came under Beijing’s sway and the consequences are there for everyone to see.