China’s deputy speaker confirmed as chief guest of Sagarmatha Sambaad

Preparations for the first-ever Sagarmatha Sambaad, set to take place in Kathmandu from May 16–18, are in their final stages.

The organizers have confirmed that all logistical and technical arrangements meet international standards to ensure the event’s success. Hosted by the Government of Nepal at the Soaltee Hotel, the dialogue will focus on the theme “Climate Change, Mountains, and the Future of Humanity.”

The high-level forum aims to address urgent global environmental challenges, particularly climate change and its disproportionate impact on mountain ecosystems and vulnerable communities. The event, which will be held biennially from now on, will convene 140 foreign delegates from 40 countries, including ministers, senior government officials, diplomats, donor agency representatives, climate experts, environmentalists, and development leaders. Together, they will seek regional and international cooperation for a unified response to the climate crisis.

According to Sambaad Secretariat Deputy Speaker of China Xiao Jie is confirmed as a chief guest of the program.

He is vice chairman of the standing committee of the 14th National People’s Congress. Other high-level guests of the programs are Bhupender Yadav, Minister of Environment, Forest and Climate Change of India, and Mukhtar Babayev, COP29 Presidency, Minister of Ecology and Natural Resources of Azerbaijan.

Lumbini: A lovely and living cultural heritage

Lumbini is a serene and sacred land in Nepal where Buddha, the Light of Asia, was born. Also known as the Enlightened One, Buddha was formerly Prince Siddhartha Gautam of the Shakya clan. He later became known as Shakyamuni and ultimately, the Buddha. Born approximately 2,700 years ago, Siddhartha Gautam’s birthplace has since been revered as a holy site for Buddhists across the world.

Located in the Rupandehi district of southern Nepal’s Tarai plains, Lumbini is a vital Buddhist pilgrimage site. According to tradition, Queen Mayadevi gave birth to Siddhartha Gautam here in 563 BCE.

Rishikesh Shah writes: “To the east of Kosala, there was in ancient times a republic of the Sakyas known as Kapilvastu. The republic was situated between the Gandaki and Rapti rivers. The Sakyas were Kshatriyas of the Ikshvaku clan, who had established their own republic after severing ties with the kingdom of Kosala. Their land extended northwards to the Himalayan ranges and southwards to a grove of sal trees called Lumbini. It was in this grove that Buddha, the founder of the Buddhist religion, was born. Lumbini is now called Rupandehi.”

Born into royalty, Siddhartha Gautam was the son of King Suddhodhan and Queen Mayadevi. He enjoyed a life of luxury and comfort. However, upon venturing beyond the palace walls, he was deeply moved by sights of suffering—a beggar, a cripple, a corpse, and a holy man. This encounter awakened in him a desire to discover the root cause of human suffering and find a path to liberation. Renouncing his royal life, he left behind his wife, Yashodhara, and son, Rahul, shedding all royal attachments to live as a wandering ascetic.

Through intense meditation and austerity, Siddhartha ultimately attained enlightenment under a Bodhi tree in Bodh Gaya on a full moon night. He experienced direct realization of Nirvana at the age of 35 and dedicated the rest of his life to preaching love, compassion, and the path to liberation until his death at 84.

The teachings of Buddha are centered on the Four Noble Truths. First, life is inherently filled with suffering. Second, the root cause of this suffering is ignorance. Third, it is possible to eliminate ignorance, and therefore suffering. Finally, the way to eliminate ignorance is through the Noble Eightfold Path. This path consists of Right Understanding, Right Aspiration, Right Speech, Right Conduct, Right Livelihood, Right Effort, Right Mindfulness, and Right Concentration. Additionally, Buddha organized his teachings under three core principles: Prajna (intellectual wisdom), Shila (moral discipline), and Samadhi (spiritual practice). These three correspond closely to the Hindu concepts of Jnana (knowledge), Karma (action), and Bhakti (devotion).

Historical and cultural significance

Emperor Ashoka of India became a devoted follower of Buddha after the devastating Kalinga war. In 250 BCE, he visited Lumbini and erected a commemorative pillar bearing inscriptions about Buddha’s birth. The inscription reads:

“King Priyadarshi, beloved of the gods, having been anointed twenty years, came in person and worshipped here, saying, ‘Here the Blessed One was born.’ King Priyadarshi exempted the village of Lumbini from taxes and bestowed wealth upon it.”

Ashoka also sent missionaries, including his son Mahendra and daughter Sanghamitra, to spread Buddhism to regions such as Sri Lanka. The site includes a sacred pond, Puskarni, where Queen Mayadevi is said to have bathed before giving birth and also washed the newborn Buddha.

Lumbini is now recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site and is being developed under the Master Plan by the Lumbini Development Trust. The area includes monasteries, stupas, meditation centers, and temples built by countries like Japan, China, Thailand, Myanmar, Vietnam, Sri Lanka, France, and Germany. Even Muslim-majority Bangladesh has announced plans to build a guesthouse for pilgrims, as noted by Ambassador Mashfee Binte Shams.

Revival and rediscovery

Lumbini had fallen into obscurity until its rediscovery in 1895 by General Khadga Samsher JB Rana and German archaeologist Alois Anton Fuhrer. Perceval Landon writes: “On 1 Dec 1895, close to the General’s camp, the great Ashokan monolith was discovered in a thicket above the surrounding fields. The site was known by the name Rummindee—a local adaptation of Lumbini.”

Chinese pilgrim records had previously described the site, including the shrine, pond, and pillar. Despite early restrictions on access, Fuhrer glimpsed a sculpture of Mayadevi inside the shrine. The art of sculpture thrived here long before the Gupta period, as evidenced by stone and terracotta statues found during excavations.

Modern-day Lumbini and its challenges

Lumbini has received increased global attention since UN Secretary-General U Thant’s visit in 1970. However, as noted by British scholar David Seddon during his 2014 visit, the site remains in a neglected state. He observed that the Ashokan pillar is submerged in an overgrown pond surrounded by broken railings and rubbish, calling for “loving care” to preserve the heritage.

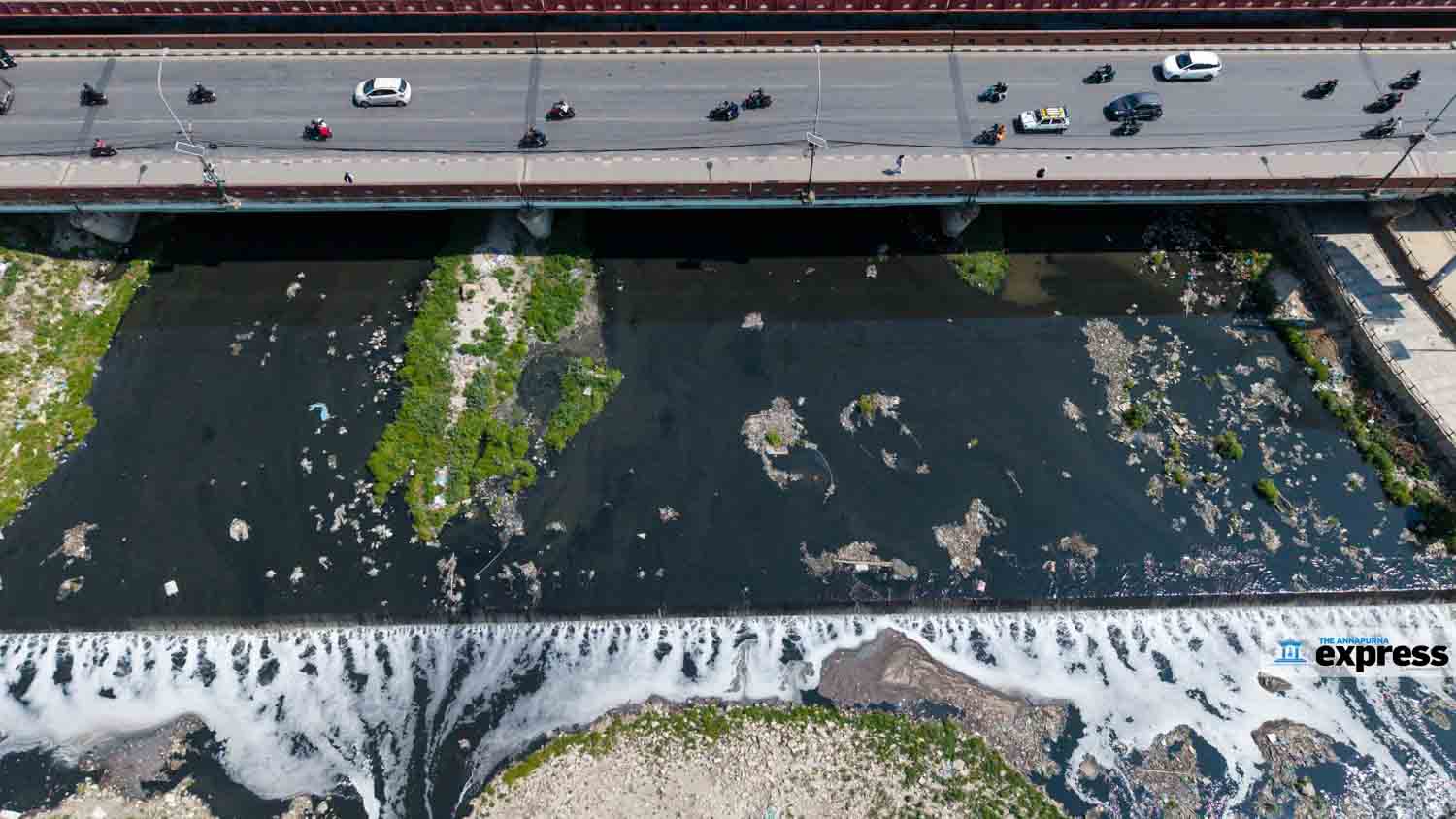

Environmental degradation is another serious concern. According to Ram Charitra Sah, Director of the Center for Public Health and Environmental Development, the proliferation of factories in the region is threatening the ecological sanctity of this sacred land.

Veteran journalist Kanak Mani Dixit has highlighted how despite Lumbini’s prominence, other archaeological treasures like Simraungadh have been neglected. He remarks that while Lumbini has become a central site in the Tarai, Buddhism remains somewhat distant from the region’s current cultural landscape.

Modern scholarship has yet to satisfactorily determine the exact date of the Buddha's Nirvana (death). Nevertheless, India and the world recently celebrated the 2,500th Nirvana Day of the Buddha based on the widely accepted timeline: his birth in 624 BC, enlightenment (Sambodhi) in 589 BC, and Parinirvana in 544 BC.

A survey conducted by Giovanni Verardi identified 136 archaeological sites of varying sizes in Kapilvastu district, with approximately another hundred sites in Rupandehi. Together, these form an extensive landscape that still requires detailed archaeological study. This abundance of sites highlights the need to shift our approach from conserving individual locations to understanding Greater Lumbini as a vast cultural landscape. Planning for Greater Lumbini must be grounded in the establishment of management frameworks that address cultural heritage, environmental sustainability, and socio-economic development.

A declaration made during the 20th General Conference of the World Fellowship of Buddhists in Sydney, Australia, endorsed Nepal’s proposal to recognize, declare, and develop Lumbini as the fountain of world peace and the holiest pilgrimage site for Buddhists. The declaration further urged that the three historical sites—Kapilvastu, Ramagrama, and Devadaha—be similarly developed and studied, alongside continued excavation, conservation, and research efforts. It also emphasized the need for a feasibility study on establishing an International Buddhist University in Lumbini and recommended identifying a suitable institution to serve as an associate center of the World Buddhist University in Thailand.

Delegates also called on the Government of Nepal to make the Lumbini Development Trust (LDT) a permanent and autonomous body and urged the United Nations to review the UN Lumbini Development Committee.

Tourism expert Kai Weise has stressed that tourism management in the region must consider the impact of the new airport, the rising number of visitors (both local and international), and the infrastructure and services needed to support them. He also emphasized the importance of protecting the environmental context of Greater Lumbini, including flood management, pollution control (from industry and other sources), and the preservation of significant landscapes through land use regulations. Opportunities for regional development, he noted, should focus on tourism as well as local livelihoods based on agriculture, handicrafts, and other sustainable services, including appropriate housing.

As the great scientist Albert Einstein once said, “If there is any religion that would cope with modern scientific needs, it would be Buddhism.” Similarly, notable figures such as Hollywood actor Richard Gere, Burmese political leader Aung San Suu Kyi, and world-renowned golfer Tiger Woods have all expressed admiration for the principles of Buddhism.

Useful skills to learn

Learning shouldn’t be limited to classrooms. We all know that but as the daily grind takes over, learning often takes a backseat. Many people ApEx spoke to confessed that without classes to attend and the threat of exams looming over their heads, they weren’t very likely to try and learn something new by themselves. While that is understandable, there are some skills that can possibly give your career a boost as well as help you feel confident about yourself. The best part is that you don’t even have to spend a lot of time every day to learn these essential skills. Just a few minutes of daily practice are enough. We recommend five handy skills that can help you become better at what you do and force you to be a little creative too, which is always a good thing.

A new language

Studies have shown that learning a new language, activates different parts of your brain and slows down age related changes. Nowadays, it’s not difficult to learn a new language from the comfort of your home. There are many apps that take you through the basics of any language you want to learn in just a few minutes a day. Learning a new language might also help you be considered for promotions especially if you work for multinational companies or open up new job opportunities. You might also be able to look into cultural exchange programs, things who previously had no access to. Additionally, learning a new language is also fun and engaging.

Basic photography skills

All of us take pictures on our phones, but how many of us can actually say that the photos we take are pleasing to look at? Learn the basics of photography through tutorials on YouTube or you can even ask a professional photographer if they would let you tag along during their assignments. Most photographers will let you assist them in their projects. There are many workshops and courses, both physical and virtual, that you can join to pick up a few tips and tricks. You don’t need fancy equipment to take good photos. Just your phone will do.

Graphic design

Graphic design is used in a wide range of fields from marketing and publishing to product design. It’s a great tool of visual communication and thus more important today than ever before. No matter which profession you are in, it helps to have some knowledge of graphic design. Are you interested in print or web design or is it motion graphics that holds a special appeal? Figure out which path you wanna take and get on board with some courses. Learning graphic design is a mentally stimulating activity.

Sewing and stitching

Many people don’t know how to mend a popped button and it’s unfortunate because you end up spending a lot of time and money fixing small things. We believe sewing and stitching are skills everyone should possess. And it’s not hard to learn either. But if you can work with a needle and thread, why not take things a step further by learning how to sew and stitch some basic items. This is something you can do as a family activity as well. Think about it, won’t it be fun to wear clothes that you made yourself? And if things turn out well, you can even start thinking of running a small clothes business in the future.

Public speaking

Everyone, irrespective of who you are and what you do, can benefit from a public speaking course. It will make you more confident and better able to express yourself. These days, many organizations and corporate houses have realized the importance of public speaking and hold workshops and training for their staff. You can also learn public speaking by listening to experts in the field and picking up pointers on how to be a more effective communicator. This is a soft skill that has huge benefits.

Sustainability in daily life

Do all the things you throw away on a regular basis—plastic bags, straws, paper, wrapping paper, cotton buds etc.—make you feel guilty? Does your trash can overflow with stuff between pick-ups? Do you find yourself wishing you could cut back on unnecessary waste but don’t know where to start? If yes, then this helpful guide is for you. Some of the things in this guide might be stuff you are familiar with but still unable to put to practice. We will help you build habits that can make sustainability a part of your daily routine without you having to put too much effort into it.

The trick to using cloth bags

We are sure everyone knows the importance of using cloth bags instead of plastic bags. Most of us have at least a few cloth bags stuffed in random drawers in our homes. But what happens is that we forget to carry these when we go out shopping and we end up either using a plastic bag or buying another cloth bag which will eventually end up in the same random drawers. The trick to make sure you don’t use plastic bags is to always have a reusable bag with you. When you put away your groceries, don’t just toss your reusable bag in a drawer. Fold it away and put it in your bag, in the dashboard of your car, or next to where you keep your keys in your entryway. This way you’ll always have a reusable bag with you on hand. You can also hang a few on a hook in the kitchen so that when you have to make impromptu grocery runs, you can quickly grab one. Make sure your cloth bags are lightweight and strong.

Reusing whatever you can

Before you throw anything away, take a look at it with fresh eyes. Most of the time, we tend to throw things that can be reused in various ways. Whether it be empty cans or jars or wrapping papers and gift bags, everything can be repurposed and used for different things around the house. You can use empty cans and jars to store spices and grains. You can repurpose them to hold pens or remote controls. The reason most of these jars and cans end up in the trash bin is because they’re hard to clean. To get pesky labels off, immerse empty jars in a bowl of water overnight and then you can simply scrub them off with a steel wool the next day. Did you know that you can repurpose gift bags to make pretty boxes that you can use to store documents and little trinkets around the house? You can find many tutorials on Instagram and Pinterest. Wine and liquor bottles can be used to store oil, as water bottles, and even as flower vases. A great way to ensure that you reuse things and don’t toss them away is to make a list of all the ways you can do just that. It helps to have a reminder on hand.

Small actions

There are many little things you can do to live an eco-friendly life, from carrying your own water bottle and metal straws to mending your clothes.

You just have to put a little thought into it but that is often easier said than done. Don’t try to make drastic changes overnight. Start with one thing at a time. For instance, in the month of May vow to not buy mineral water when you’re out. For this, you’ll have to carry your own water bottle. Invest in a steel or a glass bottle and carry water with you everywhere. Once you’ve gotten into the habit of doing this, pick up another action. Instead of carrying tissues, tuck a small handkerchief in your bag. Wherever possible, choose reusable options. Switching to a menstrual cup instead of tampons or pads can significantly lower your trash volume during your periods. The key here is not to start doing everything at once. Choose one action at a time and once you’ve mastered that move onto the next.

Buy what you need

Most of us buy things without a second thought, and it’s not unusual for us to have multiples of everything, from notebooks and stationery to cookware and bags. Impulse shopping is something that we all succumb to every once in a while. One of the main things you have to do if you want to live a sustainable life is to look into your consumption patterns. Are you buying things because you need them or because you want them? Remember that things start to lose their appeal once you’ve bought them. The thrill only lies in the purchase. When you go out shopping, make a list of things you need and only buy what’s on it. Mend your clothes so that a simple tear or a popped button does not have you running to the store to replace the item. Try using what you have at home before you buy more things. This goes for items like bags, shoes, and clothes, as well as staples like pasta and grains among others. Don’t fall into marketing traps. Understand your needs and only buy things that you know you will use.