Abusing the constitution

In his December 15 royal proclamation, King Mahendra made a number of serious allegations against the BP Koirala government, namely that it was embroiled in partisan politics, encouraged corruption, emboldened anti-national elements, undermined national unity and created a foul political climate based on hollow principles. He said, “Under the shield of democracy, the government used its authority to fulfil partisan interests at the cost of the nation and the people. Instead of honoring the law, this cabinet tried to render the country’s administrative mechanism dysfunctional in the name of making it swift, sharp and able.”

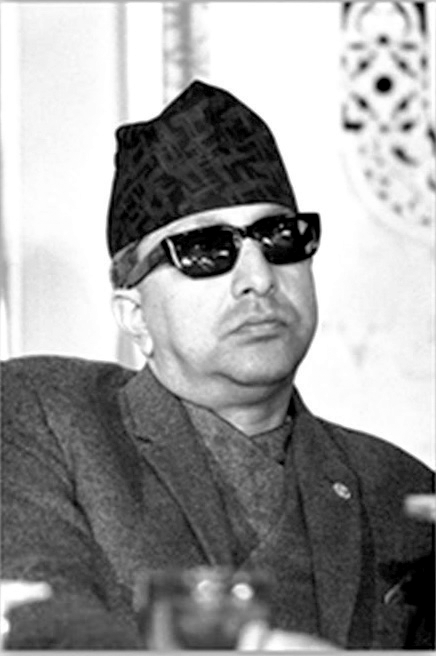

King Mahendra

The king had used just one article in the constitution to bring about the political upheaval. He had abused the ‘emergency powers’ granted to the king in Article 55. Taking a leaf out of Mahendra’s book, King Gyanendra on 1 February 2005 invoked Article 127 of the 1990 Constitution, which gave him the powers to ‘remove difficulties’, in order to seize the reins of government. While Mahendra imposed a ban on political parties, Gyanendra restricted not only political parties but also civil liberties.

The 1959 Constitution was issued under the palace’s guidance and its provisions were favorable to the king. Just one article was enough to render the constitution void. Article 55 had a provision allowing the king to exercise ‘emergency powers’ in case the country faced a serious crisis, an external attack or internal mayhem. Except for some disturbance created by people under the palace’s protection, such conditions did not exist in the country. But the constitution gave the king sole discretionary powers to assess whether the country faced an emergency situation; the government or the parliament had no say on the matter. By abusing the power vested in him by the constitution, King Mahendra staged a coup against the two-third government.

The statute even had a provision allowing the king to take over the authority enjoyed by the parliament and the government. The emergency rule could be extended for up to a year. In fact, it could be continued as long as the king was not satisfied with the state of affairs in the country. Article 56 had a provision whereby the parliament could be suspended if constitutional mechanisms failed, but it could not be dissolved.

A month after the parliament’s dissolution, King Mahendra awarded medals to a number of army and police officers for their help in the coup. Usually medals were given on special occasions, like the monarch’s birthday. But no special occasion was required to honor the aiders and abettors of the coup. Altogether 85 high-level army officials were awarded medals.

In contrast, only 26 police officers were honored, which suggests that the palace did not trust the police force as much as it trusted the army. Five other high-level officers from Singha Durbar and Narayanhiti Palace were given medals for their contribution to the royal conspiracy.

Only after 12 days of usurping the reins of power did Mahendra announce the formation of a new cabinet under his own chairmanship, where he inducted opportunist Congress leaders like Tulsi Giri and Bishwa Bandhu Thapa. Not only were Giri and Thapa the General Secretaries of the Congress, they were believed to be extremely close to BP Koirala. Giri and Thapa were also, respectively, the foreign minister in the Koirala cabinet and the chief whip of the Congress O

Next week’s ‘Vault of history’ column will discuss how the Panchayat system got its name

Death-knell of democracy

Kathmandu was not densely populated in those days. Singha Durbar was surrounded by fields where one could hear jackals howl at night. It was not easy to go to and come back from Singha Durbar in the middle of the night. There were no taxis and lawmakers had no private vehicles. Except for a few elites, almost everybody commuted on foot. “Once all the members of the House of Representatives assembled on the midnight of 30 June 1959, the Secretary read out the following letter received from the Chief Secretary of the King. To begin House proceedings, we have nominated Giri Prasad Budathoki as the executive chairperson,” states a parliamentary record.

King Mahendra had felt a sense of alarm after the Congress won a two-third majority in the country’s first parliamentary election. From the very beginning, he was into expanding the circle of people critical of the Congress. The first example of that was the nomination of the party’s loudest critics to the upper house of parliament. On the nomination list was Dil Bahadur Shrestha, who had lost in the election. Others like Surya Bahadur Thapa, Nagendra Prasad Rijal, Mukti Nath Sharma, Chandra Man Thakali, Pashupati Ghosh, and Tsering Tenzin Lama, all of whom had been defeated in the polls, ended up becoming members of the upper house. Well-known Congress denouncers like Bharat Mani Sharma, Bal Chandra Sharma and Laxman Jung Bahadur Singh were among those chosen by the king. Differences between Mahendra and BP had arisen ever since the time of the upper house nomination.

King Mahendra adopted a policy of promoting whoever reviled BP the most. Bishwa Bandhu Thapa, the then Congress whip had once told me, “King Mahendra wanted to belittle BP at any cost. But instead of doing that himself, he used others. The palace has a habit of finding people to malign those it does not approve of, while managing to maintain a veneer of respectability for itself.”

Mahendra was afraid of being a ruler in name only as long as BP was prime minister. His primary interest was to rule the country directly. To that end, Mahendra was keen on using his loyalists to discredit the prime minister and the parliamentary system.

When BP was appointed prime minister, the palace started conspiring against the Congress from within the party itself. It brought into its fold Dr Tulsi Giri and Bishwa Bandhu Thapa, who were close to BP. It started inviting lawmakers for lunch and rousing them to go against the government. King Mahendra was eager to use anyone he could find—from hermits to spies—in order make the government a failure.

On 30 January 1960, he went on a tour of western Nepal, where he said in a speech: “I also want to tell you that I have certain duties, such as protecting the sovereignty, nationality and other interests of the country. Never ever will I quit doing whatever it takes to clear any hurdle in safeguarding such interests—for which I want every Nepali’s support.”

A series of such speeches had prompted speculation that Mahendra would dissolve the government. The number of people unwilling to pay taxes and registering complaints with the palace against the government was on the rise.

Prime Minister Koirala had also suspected a conspiracy against him. Deputy Prime Minister and Finance Minister Subarna Shumsher, who was on a visit to Calcutta, had told BP that the king was planning a coup, but because the date of the British queen’s visit to Nepal had already been set, he probably would not mount it before that. Before leaving for Calcutta, Subarna Shumsher had told BP that he would discuss the king’s plan with him in detail once he returns to Kathmandu. The British queen was scheduled to visit Nepal on 26 February 1961. The Congress had guessed that a coup against a democratic government would not take place on the eve of the visit of a country’s queen where the parliamentary system was born. The prediction turned out to be stupendously wrong O

Next week’s ‘Vault of history’ column will discuss the immediate aftermath of the royal coup

Maiden meeting at midnight

After directly ruling the country for seven months, King Mahendra formed a government under Congress leader Subarna Shumsher on 15 May 1958. That cabinet consisted of Bhupal Man Singh Karki, a loyalist of Mahendra, as well as members of Gorkha Parishad, National Congress and Praja Parishad. Following the handover of power to Subarna Shumsher, Mahendra embarked on a two-month trip to Europe and Africa.

After coming back, he went on a nation-wide tour to assess the strength of the political parties. Based on all reliable sources, Mahendra came to believe that no political party was in a position to win a majority. Minister Karki even assured him that no party could win more than 40 seats in the 109-seat assembly. When the Congress ended up getting a two-third majority, Mahendra

dismissed him from his post.

King Mahendra believed the palace’s power would wane if a single party won a majority. He had been put under the impression that the Congress could garner anywhere between 30 to 40 seats. Only then had he allowed the election to go ahead. If he had assessed that the Congress could win a majority, he would once again have found some pretext to put off the polls.

The parliamentary election took place on the set date. Its result, however, turned out to be very different than what Mahendra had expected. The Congress won 74 seats in the House of Representatives. Such an impressive victory proved to be a headache for Mahendra and he dilly-dallied to announce a prime minister. BP then met him and said, “What is this, your majesty? It’s been so many days since the election took place. You don’t want me to be the prime minister. I will elect whoever you want as the party leader. If you like Subarna Shumsher, then it’ll be him.” (Bishweshwar Prasad Koiralako atmabritanta).

But Mahendra replied that since he liked “dynamic” people, he wanted to work with BP. Such a response excited the Congress leader. A party meeting was called, which unanimously elected him as its parliamentary leader. As the head of the party winning a majority, BP was constitutionally declared prime minister on 27 May 1959.

The constitution had a provision that the king would call the first meeting of the parliament. It did not specify a date though, only that the king would call it ‘as soon as possible’.

Curiously, Mahendra called the meeting in the middle of the night. The first meeting of the first directly elected parliament since the overthrow of the totalitarian Rana regime should have taken place in an exuberant mood in the middle of the day. But 11 days prior to the meeting, the palace issued a statement: “The first assembly of the House of Representatives has been called at 11:45pm on Tuesday, 30 June 1959, at the Gallery Hall

in Kathmandu.”

It was exactly midnight when the meeting commenced. Some speculated that the king chose a particularly inauspicious day and moment because of his dislike for the parliamentary system. The palace had a tradition of picking auspicious moments for itself and inauspicious ones for others. Others surmised the timing was meant to signal that it was the palace, not the parliament, which called all the shots.

Summoning the meeting at midnight was considered part of the palace’s machinations. At the time, the lawmakers did not really question the timing; they meekly went to the venue and took the oath of office. The first parliamentary meeting ended at 2:10 am.

Next week’s ‘Vault of history’ column will discuss how King Mahendra set the stage for a coup against the elected government

Mahendra’s machinations

To project himself as a progressive ruler, King Mahendra on 2 Sept 1955 announced a land policy, with a number of provisions that were deemed very popular during an era when peasants were in dire straits. It was also during Mahendra’s direct rule that Nepal established diplomatic ties with China (on 1 August 1955). Two months later, he embarked on a 14-day tour of India, handing over the reins of power to his brother Himalaya while he was away. Before leaving Nepal, he had also intensified consultations with political parties and had conveyed a message that he was committed to ‘letting democracy flourish’.

During his 11-month-long direct rule, Mahendra repeatedly spoke of the formation of a democratic government ‘suitable for the country.’ He relieved the royal advisors of their duties on 27 January 1955 and reiterated the statement: “Our faith in a democratic system remains steadfast.”

But instead of handing over power to the Congress, he appointed Tanka Prasad Acharya as the prime minister. Acharya had fought against the Ranas and was considered a ‘living martyr’. This king’s move partly fulfilled the political parties’ demands, one of which was the formation of a single-party government. But the Acharya government was mostly packed with royal loyalists. In other words, King Mahendra made sure that the government was dominated by ‘reactionaries’. Still, the parties considered it a positive step in that it had brought the king’s direct rule to an end.

Soon after the formation of the new government, Mahendra embarked on several tours across the country so as to feel the country’s pulse. Kings were confined within the four walls of the palace throughout the Rana rule; common citizens had never seem them and believed they were Lord Vishnu’s incarnation. But King Tribhuwan had not toured the country after he was released from the Ranas’ ‘cage’. The primary goal of Mahendra’s visits was to introduce himself to the citizens and to size up political parties.

Nepal’s foreign relations expanded during Tanka Prasad Acharya’s term. It became a member of the United Nations and entered into diplomatic relations with Russia and China, in addition to India, the UK and the US.

King Mahendra was a past master at using people to further his interests. Soon, he not only unseated Acharya, but also branded him as ‘the prime minister who was unable to conduct elections’. Acharya had expressed his inability to hold polls. Mahendra cited that failure and the Acharya government’s lackluster performance as the reason for dissolving it on 14 July 1957. The monarch once again used the occasion to reprimand political parties for their differences and mutual resentment.

After unseating Acharya, Mahendra had asked BP to be prime minister. But BP, citing that he had to work on party organization, recommended Subarna Shumsher for the post. That was the theoretical agreement, but the palace appointed KI Singh as the prime minister instead.

Singh’s government was formed 15 days after the dissolution of Acharya’s government. But it was also dissolved within three months, on which occasion Mahendra said: “Although I did not want to run the government, I have been compelled to.” He never failed to convey that he was tired of having to dissolve governments repeatedly.

The democratic coalition under the Congress announced a civil-disobedience movement starting 7 Dec 1957. In the political conference organized a day before in the palace in order to derail the movement, King Mahendra said, “I’m more worried than you about delaying elections.”

A week after the conference, he announced that parliamentary polls would take place after 14 months, on 18 February 1959. Breaking his father Tribhuwan’s promise for an election to a constituent assembly, Mahendra successfully oriented the country toward parliamentary elections. He formed a five-member committee on 16 March 1958 to come up with a draft constitution. Sir Ivor Jennings, a legal expert from Britain, who had written the constitution of Sri Lanka, was drafted to help the committee. He made two drafts and submitted them to the palace but, frustratingly for him, Mahendra rejected both. Only the third draft was accepted. Nepal’s first parliamentary election was held under the aegis of that constitution.

Next week’s ‘Vault of history’ column will discuss how BP Koirala came to be Nepal’s first elected prime minister

Undemocratic inclinations

The rift between the Nepali Congress and King Mahendra widened following the latter’s imposition of the ‘royal advisory rule’. The Congress called it a big blunder and a mechanism created to harass democrats. Congress leader BP Koirala said it was “a political attack by the king on the advice of those who had grown up under unitary rule.”

Thus King Mahendra made it increasingly clear that he was not willing to work with leaders who were popular among commoners and had fought for democracy. His early actions reflect his desire to be a heroic, authoritarian individual—to which end he came up with strategies to belittle political parties and their leaders.

In the face of strong criticism of the advisory rule, King Mahendra organized a political conference on 8 May 1955 at the Narayanhiti palace. But several political parties, including the Congress, National Congress and Praja Prarisad, boycotted the conference. Mahendra said that he regretted the parties’ decision and that he would not repeat past mistakes—meaning he would not accept a multi-party system. The conference assessed the previous four years of governance. King Mahendra gave a speech in which he criticized the parties’ tendency to quarrel frequently and topple governments just a few months after their formation.

The speech rankled the parties further. They said it was merely a way to denigrate them. Mahendra kept moving in the direction of tiring out and coaxing the parties. “I don’t want to lose democracy. With your consensus and recommendation, I want to place this important burden on able shoulders,” he said at the conference, which was filled with his near and dear ones. But even they advised the monarch against direct rule. They also suggested him to hold elections and establish a democratic system—to which Mahendra replied by saying, “They are not trivial matters, but it would not be wise to make rash decisions either.”

Because of the absence of major political parties, the conference was deemed a failure. Political leaders viewed Mahendra’s activities with suspicion. That the monarch could kill democracy at any moment was their preliminary conclusion.

King Mahendra defended direct rule every time on the grounds that circumstances demanded it. He was in a situation where he could not trust any political party. At the palace conference, he had said, “Undesirable elements are likely to win if there is an election now, so we should only conduct an election two or three years later, after we can instill civilian sentiments in the people.” (Shree Panch Maharajadhiraj Mahendra Bir Bikram Shah Dev baata bakseka ghosana, bhasan ra sandeshharu (2022), Panchayat Mantralaya

As the Congress was a strong political force, Mahendra’s plan was to break it before holding elections. From the very beginning, he started plotting against the party. Gradually he got his loyalists to infiltrate political outfits and appointed his supporters to the country’s governing bodies.

Elections had not been held in the country in accordance with democratic principles. The Congress had been demanding an election and a one-party government. Meanwhile, on 8 August 1955, Mahendra announced that polls would be conducted after two years. He claimed that although he wanted to hold them sooner, ‘circumstances’ made it possible only in October 1957. The unusually long deferral made the Congress suspect

something was fishy.

The Congress, National Congress and Praja Parishad formed a loose coalition that launched a movement to advocate forming a government led by a party rather than an individual in order to improve the country’s situation and establish a democratic system. They demanded that one among the three parties head the government. They also insisted that Gorkha Parishad and reactionary elements be left out of the government.

Next week’s ‘Vault of history’ column will discuss the tumultuous run-up to the country’s first parliamentary election and its aftermath

Enter Mahendra

“Democracy is the legacy of my father,” said King Mahendra upon ascending the throne. “Let’s vow to promote and nourish democracy.”

Mahendra’s actions and policies, however, were never in favor of preserving his father’s legacy. He was always drawn to direct rule. He had become king four years after the dawn of democracy in the country. Democrats kept accusing him of being ‘the murderer of democracy’ after Mahendra jailed those who had fought for democracy and moved steadily in the direction of authoritarian rule.

His father King Tribhuvan, a heart patient, had gone for treatment to Switzerland, where, after six months, he breathed his last on 13 March 1955. Mahendra’s coronation took place the following day. In fact, by dissolving Matrika Prasad Koirala’s cabinet while Tribhuvan was still alive in Switzerland, Mahendra had already shown an inclination for direct rule. This meant when the ‘father of democracy’ passed away, the country did not even have a civilian prime minister.

Mahendra’s relationship with Tribhuvan was strained, particularly after he married his sister-in-law Ratna against his father’s wishes. Tribhuvan did not even attend

the wedding.

Mahendra’s 17-year-long reign helped shape his mixed character. On the one hand, he was an enemy of democracy and a plural, parliamentary system. On the other, he strengthened nationalism and helped Nepal find a place on the international stage. At the time he became king, Indians wielded strong influence in Nepal’s ruling circles; they interfered openly in the decisions of the palace and the cabinet. Mahendra reduced the degree of interference and even created a situation where the Indians had to employ spies to find out about cabinet decisions.

Mahendra disliked politicians and the parties they represented. A month after his coronation, he addressed the nation on the occasion of the Nepali new year, saying, “We have to tread carefully in order to strengthen democracy and prevent it from being tarnished.” But he also said that he would assume control until a “popular cabinet can be put in place.” He formed a ‘Civilized Royal Commission’ and sent its members on a nation-wide tour “in order to understand and solve the problems facing the people.”

But it was never made public who were part of the commission. Rumors started circulating that the monarch had sent a motley crew of mendicants and security personnel across the nation for spying purposes.

Having repeatedly heard Mahendra extol the virtues of democracy, many believed he would stand in favor of a multi-party system. But by setting up a five-member royal team, he veered toward ‘advisory rule’, and set the stage for ‘direct rule’. The members of the royal advisory team were not common citizens. Nor had they fought for democracy. They were mostly courtiers, priests, industrialists and palace loyalists.

In fact, they were close to the Ranas in one way or another. The team was headed by Sardar Gunjaman Singh, who was considered a successful businessman and an able administrator during the Rana rule. His deputy was Lieutenant General Ananda Shumsher Jung Bahadur Rana, whose aim was to win the support of the Ranas with clout in the army.

Next week’s ‘Vault of history’ column will discuss the wrangling between King Mahendra and political parties

Matrika’s fall from grace

The biggest blot on Matrika Prasad Koirala’s political career was the Koshi agreement. He constantly faced accusations of being “the Koshi seller”. Since 1954, Koshi daan (‘Offering Koshi’) to India has been a persistent political slogan in Nepal. The Nepali Congress is also associated with the Koshi agreement, although no one from the party was in the government when it was signed. In fact, when the agreement was signed on 24 April 1954, the Congress was barely on speaking terms with the Matrika-led government.

The agreement—signed by Mahabir Shumsher Rana, Nepal’s project development minister, and Gulzarilal Nanda, India’s planning minister—was about the construction of a dam to control the flow of the Koshi River. Preliminary study on the project had already begun during the Rana rule. The agreement became contentious as it was signed at a time when the Indians held strong sway over Nepal’s ruling circles, and particularly after Nepal failed to derive ‘significant benefits’ out of it. Matrika was very close to Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. He used to consult with Nehru on even minor issues and made decisions accordingly.

During monsoon, the Koshi River used to inundate the Indian state of Bihar, so India desperately wanted to build a dam. (The river is still known as ‘the sorrow of Bihar’.)

Matrika reasoned that if Nepal did not allow the construction of a dam in its territory, India would build one a bit lower down at Tedhibazaar and inundate Nepal. He was therefore eager to sign the agreement. But because Nepal could not offer an alternative to the engineering model suggested by India, the Indian proposal prevailed.

It seems the Indians badly misled their Nepali counterparts. Laxman Prasad Rimal, a secretary at the then canal and power ministry, has written: “The day before the signing of the agreement, we had clearly concluded that Nepal would hand over the Koshi barrage to India on a 99-year lease. Although the Indian side wanted it to be 199 years, we had agreed on 99. But later we found out that the formal agreement stated 199 years. I turned completely pale.”

According to Himalaya Shumsher Rana, the then finance secretary, “The Indians had made many demands regarding the execution of the Koshi barrage project. There was a provision that would completely hand over the dam’s maintenance to the Indians. We had maintained that such provisions would be unacceptable, but our ministers overrode our objections and signed the agreement.”

The technical aspects of the project were not thoroughly discussed. Many believed that the deal was signed hurriedly and unscrupulously. As a result of the Koshi agreement, Matrika could not establish himself firmly in the hearts of Nepalis.

King Tribhuvan had been to Switzerland for medical treatment, and his son Mahendra was in charge of governing the country. Mahendra was not happy with Matrika. Rumors about Matrika’s imminent ouster were circulating.

Matrika received assurances from Mahendra that he would not be ousted. And he believed it. But on 2 March 1955, as a cabinet meeting was taking place, a letter from the palace suddenly arrived. After reading it, Matrika remarked, “I’m no longer the prime minister and you’re no longer ministers.” Matrika was thus kicked out ignominiously.

Mahendra took over the country’s governance, arguing that “putting in place a competent cabinet that works in the country’s interest would require some time”. And when King Tribhuvan passed away in Switzerland a few days later, the reins of power fell completely into Mahendra’s hands.

Matrika never got an attractive position after that. With King Mahendra’s good graces, he did become a member of the Upper House a few years later. But he never stopped aspiring to the prime minister’s post. He kept spurring the monarch to impose direct rule on the grounds that the BP Koirala government (elected in 1959) was corrupt.

On 15 December 1960, King Mahendra did stage a coup against the two-third majority BP Koirala government. The Koirala family was scattered. Following the advent of the Panchayat regime, some Koiralas were in jail while others were living in exile. The palace kept using Matrika; he was appointed ambassador to the US. This was a curious turn of events as Matrika had already been a prime minister.

Subsequently, he was appointed a National Panchayat member on 11 June 1978—which was the only politically profitable position he got during the Panchayat era. But throughout that era, Matrika was considered a potential prime ministerial candidate. In 1985, he contested an election to the National Panchayat from Morang but was badly defeated. After that, he was no longer a part of the ruling circle.

Following the fall of the Rana regime, Matrika had become the county’s first civilian prime minister with great dignity. Subsequently though, he failed to maintain the same level of dignity as a leader. He died on 11 Sept, 1997.

Next week’s ‘Vault of history’ column will discuss King Mahendra and his lack of commitment to the democratic process

Revolutionary turned royalist

Matrika and BP were half-brothers. While Matrika was the son of Krishna Prasad Koirala’s first wife, BP, Tarini, Keshav and Girija were the sons of his second wife. Three members of this family ended up becoming prime

ministers.

The quarrel between Matrika and BP made the country unstable. In a sense, Nepal was locked in a political transition. In May 1952, a special convention was held in Janakpur, which turned into a battlefield of sorts because of the brothers’ jostle for party presidency.

A number of Congress leaders left not just the convention, but the party itself. Then Prime Minister Matrika realized that BP exercised total control over the Congress, so he did not dare file a nomination for party presidency. As a result, BP was elected to the post without difficulty. Still, Matrika imposed a condition that the party would not interfere with government functioning.

After the convention, two factions—led by Matrika and BP—were firmly established within the Congress, and the party came out strongly against the government. It demanded that the government be “solid, bold and substantive.” It even sought a cabinet reshuffle and sent its list of candidates. It applied pressure on the government to rid the cabinet of independent ministers and fill it entirely with Congress members. But the prime minister did not heed the party’s instruction.

The Congress did not take Matrika’s defiance lightly. Upon its instruction, a number of ministers—Subarna Shumsher Rana, Surya Prasad Upadhyaya, and Ganesh Man Singh—resigned. At the same time, Matrika Prasad Koirala, Mahabir Shumsher Rana and Mahendra Bikram Shah resigned from the party’s central committee—but not from the government. The Congress then issued a second instruction, enjoining its ministers to quit the government within 48 hours. But Matrika maintained that the party did not have the right to issue instructions without considering their “context, legitimacy and utility.”

Matrika did finally resign from the prime minister’s post on 10 August 1952. And he was no longer a general member of the Congress. His resignation meant that the prime minister’s post became vacant. Following this King Tribhuwan formed an ad-hoc government under his own chairmanship, excluding the Congress. For 11 months, the country was without a prime minister and was ruled directly by the monarch.

Matrika formed a separate party—the Rastriya Praja Party—after he left the government and the Congress. The health of King Tribhuvan, a heart patient, was deteriorating and he was having trouble governing the country directly. He wanted to bring the prime ministerial system back. But BP was not in his good books. The king openly expressed his desire to pick someone from a small party. He made indirect accusations against the Congress and its leaders that they were mired in personal and partisan issues and had failed to formulate a national vision.

He argued that the number of votes did not determine a party’s strength and announced the formation of a government led by the Rastriya Praja Party. As a result, Matrika became prime minister for the second time on 15 June 1953. Eight months later, the cabinet was reshuffled and it included Keshar Shumsher Rana, Dilli Raman Regmi, Tanka Prasad Acharya and Bhadrakali Mishra, among others.

Unlike in his first term, Matrika did not enjoy strong political support, only the king’s good graces. He started blindly accepting every instruction of King Tribhuvan and his Indian advisor Govind Narain. It was natural for the Congress to dislike his cabinet, but even other parties did not approve of it.

To keep Matrika happy, the palace also bestowed upon him the title of an honorary general of the Nepal Army on 9 July 1954. Matrika was over the moon. The post of an army general was still confined within the Rana family. Although Matrika’s post was honorary, he appeared in military attire in Tundikhel to take the salute—something that drew flak from political quarters.

To please the palace, Matrika coined a term—‘Maushuf’. On 7 August 1953, less than two months after being appointed prime minister for the second time, he issued an instruction to use ‘Maushuf’ to refer to Shree Panch Maharajadhiraj and the royal family. Soon the usage became legally binding. Earlier, the Nepali term of respect—‘Wahaan’—was used to address royal members. Now that the monarchy has been abolished, the term ‘Maushuf’ has been consigned to the womb of history.

Next week’s ‘Vault of history’ column will discuss the Koshi agreement and the subsequent downfall of Matrika Prasad Koirala