Jessica Stern: Nepal a beacon of hope for South Asia’s LGBTIQA+ community

Appointed by President Joe Biden in June 2021, Jessica Stern is an US special envoy to advance the human rights of LGBTIQA+ persons. She specializes in gender, sexuality and human rights globally. Her role as a special envoy is to ensure that American diplomacy and foreign assistance promote and protect the human rights of the LGBTIQA+ community around the world. She recently visited Nepal and met several members of Queer community, government officials and other stakeholders. Kamal Dev Bhattarai of ApEx caught up with her. What is the purpose of your Nepal visit? One of my responsibilities is to identify the countries that have best practices on people belonging to this community. There is not a country on the planet that does not discriminate against this community. The question is: How can we accelerate the pace of change, what policies and programs should governments invest in so that members of this community enjoy citizenship rights? Nepal has been at the vanguard in terms of recognition of this community in the constitution and seminal Supreme Court decision. Actually, the US can learn a lot from Nepal when it comes to the legal arrangements. I came to know how this community is living here. During my stay in Kathmandu, I talked with more than 50 members of this community, government officials and representatives of institutions working on Queer issues. What major concerns did members of this community share with you? I heard that transgender people still experience high-level of discrimination and violence and it is very difficult for them to change the citizenship document. And without access to legal documents that reflect your gender marker, it is tough to get a job, housing and other facilities. People of this community want access to equal marriage, they want to be able to adopt children and they want to be recognized as parents. How do you see the legislative status of Nepal with regard to queer rights? When I spoke with members of this community here, I came to know that they want a broader rape law because any person of any gender and sexual orientation can be a victim of rape. They want an easier pathway to citizenship recognition. People want equal marriage. They want to be entitled to full protection that every citizen is provided. And women want to pass citizenship to their children. That is the priority for the people here, not only for the heterosexual people but all women. When women are not seen as full citizens in the eyes of law, it has spillover effects at the community level. How do you compare Nepal’s status on queer people to other South Asian countries? Nepal is a beacon of hope in this region. LGBTIQA+ communities in other countries often say: We want to be more like Nepal, Nepal has received recognition from the court, they get meetings with the government and they are not criminalized. I think these are the markers of success in the region. Nepal is a symbol of hope on queer rights. The country is a leader in this region on human rights of these people. If there is further progress on LGBTIQA+ issues, it will not only be good for Nepal but also for entire South Asia. LGBTIQA+ communit y still faces discrimination in Nepal and many members are not ready to come out. What are your suggestions? A lot of people are still afraid to come out because of practical reasons. When you come out, there is a risk of family rejection. Many communities cannot live with their family because they are not accepted. I met those people who were homeless because it is difficult for them to find a landlord. Many of them are unemployed or underemployed. We should think about how everybody can support them. It is very simple: respect all people, love your children no matter who they are, do not reject them. Governments in all countries, including here in Nepal, need to ensure the most vulnerable get additional support. They should certainly get more resources.

The ever-evolving Nepal-India relations

This year marks the 75th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic ties between Nepal and India. While the two countries formally started diplomatic relations on 17 June 1947—two months before India gained its independence from the British—it was the Peace and Friendship Treaty of 1950 that laid the foundation for future Nepal-India ties. The treaty formalized the open border between the two countries, facilitating people-to-people connections, which makes the Nepal-India relationship both unique and strong. Over the past seven and half decades, the two countries have seen many ups and downs in their relations. But India remains a key development partner of Nepal. Ranjit Rae, former Indian Ambassador to Nepal, says this relation is characterized by shared civilization: “[Nepali and Indian] societies have been nurtured and nourished by the same mountains and rivers.” Open borders, he says, has led to a seamless movement of people, goods and services, contributing to fraternal relationships between the two countries and their peoples. Despite fluctuating relations at the political level, the development partnership between the two countries is ever-expanding. The key areas of partnership between Nepal and India are connectivity, health, education, energy, education, defense and infrastructure projects. Nepal occupies a special place in India’s ‘neighborhood first’ policy. In his Independence Day message, Indian Ambassador to Nepal Naveen Srivastava spoke of how common cultural tradition remains the pillar of development partnership between India and Nepal. Lok Raj Baral, former Nepali ambassador to India, agrees that Nepal-India bond is special, one that cannot be disturbed by disagreements at the political level. There has been no substantive change in our bilateral relations in the past 75 years, he notes. “The substance and structure of our relationship remains the same,” he adds. CPN-UML leader Deepak Prakash Bhatta says it is the people-to-people connections that keep the ties between Nepal and India strong even in the face of disagreements between the two governments. For example, the 1950 Peace and Friendship Treaty has long been a bone of contention between them, for example and the issue of its amendment has cropped up time and again, to no avail. Making changes to the bilateral arrangements, which have been in place for the past 75 years was among the recommendations made by the Eminent Persons’ Group (EPG), a joint body of the two countries formed to update bilateral treaties. But India has yet to officially accept the report to take matters forward. Many doubt India will ever consider reviewing its treaties with Nepal. Bhatta says that in all negotiations with India since 1950, Nepal’s position has always been weak, which has led to unequal agreements. There are also boundary disputes in Kalapani, Lipulekh and Limpiyadhura areas. The issue is being discussed bilaterally, but without much progress. But former ambassador Rae believes issues between the two countries can be resolved through dialogue and negotiation “while keeping in mind the concerns and interests” of both the sides. India’s sustained influence over Nepal’s internal politics has also been a widely discussed and criticized subject. Yes, India had supported Nepali political parties during major political movements, but it is also true that New Delhi has sometimes tried to dictate Nepal’s internal politics. Rae says India has always backed the aspiration of the Nepali people for a multiparty democracy. He disagrees that India meddles in Nepal’s internal affairs. “India has been closely associated with each phase of Nepal’s political and economic transformation,” he says. From the Delhi pact of 1950 to the first Janandolan of 1989-90, Rae points out, “from the peace process that began in 2005 to an agreement between Nepal government and Madhes-based parties in 2007.” Nepal has always tried to decrease its dependence on India, mainly on trade, and thereby temper India’s clout. Baral, former Nepali ambassador to India, says Nepal adopted the policy of trade diversification but instead of boosting domestic productivity it led to further increase in imports. Nepal’s economy became weak as a result and dependence on India only increased. Nepal has also signed the Transit and Transport Treaty with China but, again, to no visible benefit for the Himalayan country. UML leader Bhatta partly blames India for the swelling trade imbalance. “As a close neighbor India has a certain responsibility to settle tariff and non-tariff barriers along with offering quotas for Nepali products—which it has not done.” A lot has changed in the past seven decades. India’s influence in South Asia has waned with the rise of China, another close neighbor of Nepal. China and India are the two major players in South Asia, as well as regional rivals, and each wants Nepal on its side. A senior Indian government official says New Delhi’s major concern is China’s growing influence in Nepal’s internal politics. The historical Nepal-India ties stand at a crossroads, particularly given the tense relations between India and China. Of late, the US has also increased its activities in Nepal in a bid to counter China. India is closely watching the growing US-China competition in Kathmandu. But Rae is optimistic “The future of Nepal-India relations,” Rae adds, “will certainly be better than what they were in the past.”

InDepth: Where is the synergy in Nepal’s energy policy?

Nepal has set the target of net-zero emissions by 2045. It’s an ambitious, but not an impossible, goal—if only the government had a good energy policy, say energy experts.

Multiple actors are attached to Nepal’s energy sector and they are all working with separate visions, policies and priorities. There is no umbrella policy and no apex institution to give them direction.

Madhusudhan Adhikari, executive director of Alternative Energy Promotion Center, says policy-makers are themselves misguided.

“They think energy means exclusively electricity when the contribution of electricity in our energy mix is under 10 percent,” he says. “When we discuss energy in Nepal, we are debating that small percentage.”

Nepal’s key sources of green energy are hydro, solar and wind. Until now they are independent of one another. Companies and institutions engaged in the production and distribution of energy are not working with a single purpose.

To achieve net-zero, policymakers should be thinking about phasing out fossil fuel and biomass, as well as increasing domestic consumption of clean energy and exporting surplus energy. There is a desperate need for better coordination among government agencies.

In 2017, the Asian Development Bank advised the Nepal government to formulate and implement a national energy security policy. The need for such a policy had become vital, particularly after the country adopted a three-tier government system.

Nepal’s current energy policy places hydropower at the top. This approach needs to be re-oriented as the country is not sufficiently utilizing modern and clean energy.

“We have the Energy Ministry but it largely functions as a hydroelectricity ministry,” says Adhikari. “This shows a lack of clarity in vision.”

The electricity sector isn’t faring well either. The Nepal Electricity Authority (NEA), the state power utility, hasn’t been able to provide enough electricity in rural areas. Electricity distribution through transmission lines in some topographically challenged mountain and hill areas is either impossible or highly expensive.

This is where alternative energy could have filled the gap.

The onus for formulating a comprehensive energy policy lies with the Ministry of Energy. But the task is almost impossible due to frequent government changes. Successive energy ministers are keener to announce populist agendas instead of working on a long-term policy.

The National Planning Commission and Water and the Energy Commission are also responsible for guiding the government. Yet these two bodies have done little to review Nepal’s energy policy in line with the changing needs.

“The priority is mostly hydro and then solar,” says Shailesh Mishra, chief executive officer of Independent Power Producers Association. “There hasn’t been much deliberation on an umbrella energy policy.”

During the Panchayat regime, Nepal had no energy policy. It was the NEA’s responsibility to manage the country’s hydropower. In 1992, the Hydropower Development Policy was formulated, with the prime objective of motivating the private sector to invest in hydropower development.

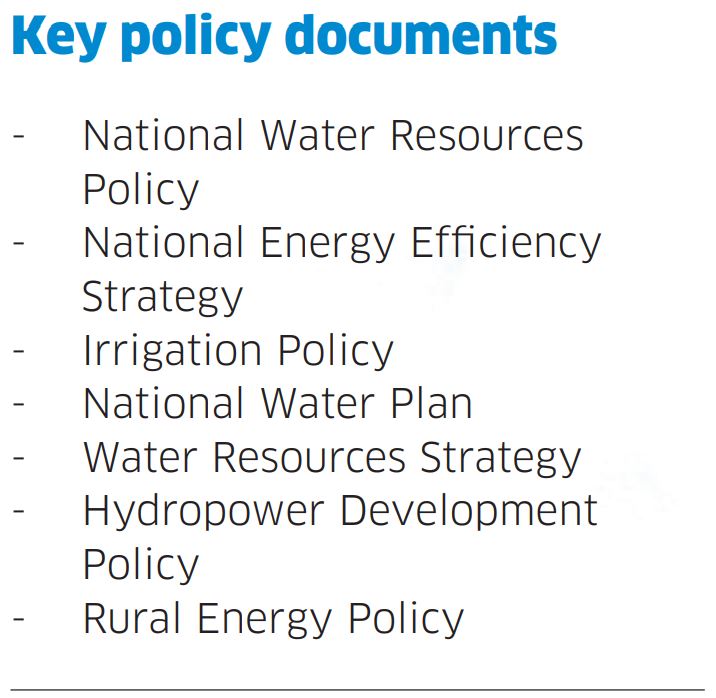

The hydropower policy more or less remains Nepal’s only energy policy. Some key policies that the government has introduced over the past three decades were also related to hydro, such as the National Water Resources Policy, the National Energy Efficiency Strategy, the Irrigation Policy, the Nepal Water Plan, and the Water Resources Strategy.

Talks about policies for other sectors began in earnest in the 2000s. In 2006, the Rural Energy Policy was promulgated to provide biomass technologies and off-grid micro-hydro systems for rural electrification. Later, there were initiatives to explore alternative energy sources in solar, wind biogas and micro-hydro.

It was only in 2013 that Nepal introduced its “energy vision” that talks about integrated policy to handle the energy sector.

“Discover, explore, develop and manage sustainably all the available potential energy resources in the country,” says the document. It also points to the need for a “high-powered umbrella organization” to implement a uniform energy policy, as well as a national energy regulatory commission to coordinate with all state agencies.

Maheshwor Dhakal, joint secretary at the Ministry of Forest and Environment, points to an urgent need for a comprehensive energy policy in order to phase out the use of fossil fuels and switch to clean energy.

The absence of such a policy, he says, signals an abject lack of coordination among key state institutions in the energy sector.

“Along with the policy, Nepal also needs a separate ministry to look after energy-related issues, particularly as we have already pledged to embrace green energy,” adds Dhakal.

Krishna Prasad Oli, a former National Planning Commission member, however, faults the lack of coordination rather than the energy policy per se.

He says before initiating any homework on an integrated energy policy, there should be a comprehensive study on possible areas of improvement.

“Let’s first identify the bottlenecks,” he says, cautioning against jumping to a conclusion that a single policy will resolve everything.

Oli strongly believes that the heart of the problem lies, again, in lack of coordination and regulation. “A letter from Nepal Electricity Authority takes a whole month to reach the Energy Ministry. Many such lapses have gone unaddressed.”

Oli also advises energy experts and policymakers to consider energy security that has been given very little thought.

Nepal relies heavily on imported fuels, but there is as yet no plan to prevent the kind of acute energy-insecurity seen post-2015 blockade.

External stakes in Nepal’s parliamentary elections

Nepal will vote on November 20 to elect new representatives to the federal parliament and provincial assemblies.

In a way, these elections will be more than a periodic democratic exercise. External forces, China and the US in particular, will be highly interested in knowing which party forms the government in Kathmandu for another five years.

It would be a folly to imagine otherwise in the current geopolitical climate, says foreign policy analyst Geja Sharma Wagle.

As the US and China compete for influence in South Asia, he says the two global powers are “keenly observing” Nepal’s political developments.

“The foreign policy priorities of the new government will directly impact them,” Wagle adds.

The effects of US-China tensions have already manifested in Nepal’s national politics, as the political parties are divided on issues where Beijing and the West do not see eye to eye.

Most recently, two former communist prime ministers Pushpa Kamal Dahal and Jhala Nath Khanal deplored US House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s Taiwan visit.

Earlier, communist forces, including those in the ruling coalition, had objected to the government’s position on the Russia-Ukraine war. They criticized the Nepali Congress-led government for deviating from Nepal’s non-alignment policy and taking the American side by condemning Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The maneuverings of the US and China in Nepal reached the level of open name-calling earlier this year over the America’s Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) Nepal compact.

It is no secret that both the US and China are trying to pull Nepal into their orbit and each wishes to see a favorable government in Kathmandu.

Nepali political parties have also left little to the imagination on whose side they stand on.

“Nepali leaders from across the political spectrum have this tendency of seeking outside blessings,” says political analyst Chandra Dev Bhatta. “Their sycophancy has created space for external forces to influence our internal politics.”

True, it is up to the Nepali voters to choose their government but you cannot overlook the influence of foreign powers over the electoral process. “The outside forces, for instance, can influence the formation of electoral alliances,” says Bhatta.

It is clear that China prefers the unification of Nepal’s communist forces as Beijing wants a powerful communist government in Nepal. It had played an instrumental role in uniting two of Nepal’s most prominent left parties, CPN-UML and CPN (Maoist Center), post 2017 polls.

The result of that union was the erstwhile Nepal Communist Party (NCP), the largest communist party in the country’s history, which commanded majority seats in Kathmandu and six of the seven provinces.

Although the party collapsed within a few years due to infighting, China has still not given up on its communist project in Nepal. If not the party merger, Beijing wants Nepal’s communist parties to forge an electoral alliance at the least.

During his Nepal visit in the first week of July, Liu Jianchao, head of the International Liaison Department of the Chinese Communist Party, met Nepal’s communist party leaders in a bid to encourage them to come together.

The US and its western allies, on the other hand, do not want a pro-Beijing communist government to lead Nepal.

“The democratic world wants to see a government led by a non-communist party,” says Wagle.

For the US and by extension the West, the main goal is to counter China’s growing influence in Nepal. They are willing to back the political parties that are committed to implementing the 2015 constitution.

India, which holds considerable sway over Nepal’s internal politics, is wary of China’s growing activism in Kathmandu—or of the Americans, for that matter.

Over the past few years, India has maintained a low-key approach to Nepal’s internal politics. The government of Narendra Modi in New Delhi is more focused on building party-to-party relations with Nepali forces: it does not want to support one party at the risk of antagonizing another.

India knows that Nepal’s communist parties can easily whip up anti-Indian sentiment among voters. So it is willing to work closely with whichever party comes to Baluwatar. New Delhi will be content so long as the next government in Kathmandu does not lean towards Beijing.

A New Delhi-based diplomatic source says India has urged Maoist chairman Pushpa Kamal Dahal not to break the current five-party ruling coalition. Dahal too has assured senior Indian officials that his priority is also the continuation of the coalition.

Bhatta says the extent of external influence in Nepali political parties will be further clarified during the formation of the post-election government.

“All the powers who have interests in Nepal will try to bring to power the political parties they feel comfortable with,” Bhatta says.

Zhiqun Zhu: Focus on development. Do not get involved in great power rivalry

US House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s recent Taiwan trip has greatly strained US-China relations. Beijing has called the visit “irresponsible and irrational” and suspended all engagements with Washington on military, climate change and other crucial issues. What’s next for these two competing powers and how will their future relations affect the world order? Kamal Dev Bhattarai of ApEx talks to Zhiqun Zhu, professor of political science and international relations as well as the inaugural director of the China Institute, at Bucknell University, US.

How did you see the US House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan?

It’s totally imprudent at a time US-China relations are in a terrible shape. She shrugged off repeated warnings from China and dismissed serious concerns from the Biden administration and many well-respected scholars and former government officials. She knew the risks associated with this trip, which is why she did not include Taiwan in her published itinerary and kept everyone guessing even after she had started the Asia trip. Despite the misgivings, she proceeded with the controversial visit. It was this irresponsible behavior that led to the current tensions in East Asia.

Has there of late been any shift in America’s ‘One China’ policy?

The core of America’s ‘One China’ policy concerns Taiwan’s status. It is based on the three PRC-US joint communiqués and the Taiwan Relations Act. The US acknowledges the Chinese position that Taiwan is part of China and only maintains unofficial relations with Taiwan. Recently, the US has added the Six Assurances—the Reagan administration’s principles on US-Taiwan relations—to its definition of ‘One China’.

Both the Trump and Biden administrations upgraded US-Taiwan relations, such as signing the Taiwan Travel Act into law and lifting restrictions on interactions between US and Taiwan officials. The US government has also publicly admitted to the presence of a few dozen US troops in Taiwan. One doubts whether Washington still strictly follows its ‘One China’ policy or has moved to ‘One China, One Taiwan’ policy.

How do you see the growing competition between the US and China in the Indo-Pacific region?

A rising tide lifts all boats. So a healthy competition is good. However, the US and China today are engaged in a zero-sum or even negative-sum competition in the Indo-Pacific.

China has become more assertive in foreign affairs as its power continues to grow. It is more willing to use hard power to deal with disputes with other nations. The US, meanwhile, has formed new or strengthened existing multilateral groups to counter China, such as AUKUS, QUAD, and Five Eyes.

The US is also promoting a free and open Indo-Pacific and has launched the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework, in which China is not included. This has raised concerns that the framework may be an anti-China group.

South Asian countries are feeling the heat of deepening US-China rivalry. What are your suggestions for smaller countries in the region?

When the two great powers are competing ruthlessly, there is not much small countries can do. The best strategy for small countries in South Asia and elsewhere is perhaps to focus on domestic development. Do not get involved in the great power rivalry.

And if some small countries prefer to be more vocal, perhaps they can learn from Singapore and tell the two great powers to not force them to choose sides, and resolve the differences peacefully.

What are the prospects of US-China relations?

The US will do its utmost to maintain global supremacy and will push back any challengers. China is marching towards realizing the ‘Chinese Dream’ of restoring its historical status as a wealthy and powerful nation. China may not be interested in replacing the US as the global power, but its rise is threatening America’s dominance. Given the structural conflicts, the prospects of US-China relations are not promising. The only way out of this dilemma is to face the reality, respect each other’s legitimate rights and focus on areas of common interests. The two great powers will have to learn to co-exist peacefully while working together to tackle global challenges such as climate change.

Focus on elections, not foreign trips

Heading into the single-phase federal and provincial elections on November 20, speculations about foreign meddling are rife. New Delhi would like to see the continuity of the current five-party coalition. This is also something that has been clearly conveyed to senior Nepali Congress and CPN (Maoist Center) leaders during their recent trips to BJP headquarters.

If PM Deuba’s relations with New Delhi are pally, he has even better ties with Washington DC. He spent considerable political capital in pushing the MCC compact through the parliament, and he was keen on the passage of the IPS-linked State Partnership Program (SPP)—perhaps he still is. It is unclear what the government has written in its letter to the US on the SPP: has Nepal given up on the program for good or it is only a temporary pullout? Things should get clearer during the PM’s (long-delayed) US trip.

Meanwhile, our foreign minister Narayan Khadka visited Beijing, in what many saw as a sign of a thaw in Nepal-China relations. There have been a spate of bilateral visits and the two countries’ dispute-resolution mechanisms have also been activated. But Beijing still doubts the overtures of the ‘anti-China’ government in Kathmandu. While Khadka was in Beijing, Wang Yi, China’s foreign minister, sought from him Nepal’s support for China’s position on Taiwan. In fact, China has been seeking similar support over Taiwan from countries the world over. The Chinese will not desist from some arm-twisting if that is what it takes.

In these times of pitched geopolitical battles, could big powers also try to somehow meddle in elections? “It is up to Nepali voters to choose their government,” says political analyst Chandra Dev Bhatta. But the outside forces can certainly try to influence elections, for instance “by helping with the formation of certain electoral alliances.” It is indeed strange that while elections should be the sole focus of the caretaker government, all kinds of foreign trips and adventures are being undertaken.

Are Nepal-China relations thawing?

The relations between Nepal and China started floundering following the formation of the Sher Bahadur Deuba government in July 2021.

For most of the past 13 months, the two sides showed little enthusiasm for mutual engagement. Beijing saw the Deuba-led government as pro-western. The government on its part also kept a safe distance from the northern neighbor and kept its foreign engagements more or less limited to India and Western powers.

The two sides resumed bilateral dealings only in recent months. After China’s two back-to-back high-level trips to Nepal—Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi visited in March and the Chinese Communist Party’s International Liaison Department head Liu Jianchao came in July—Foreign Minister Narayan Khadka this week made a reciprocal visit to Beijing.

“The visit aims to build an atmosphere of trust to further enhance our long-standing cordial relations,” says Arun Subedi, PM Deuba’s foreign affairs advisor.

The soured Nepal-China ties appear headed for a thaw. The resumption of the meetings of bilateral mechanisms, including one related to border management, is one indication of this.

Khadka held talks with his Chinese counterpart Yi on bilateral and regional issues. By inviting Khadka, China, meanwhile, wants to seek fresh assurance from Nepal on ‘One China policy.

This is particularly important for Beijing at a time its ties with Washington are at a historic low following US Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s Taiwan sojourn last week.

Prior to Khadka’s China trip, his ministry on August 5 had issued a statement essentially vowing Nepal’s steadfastness to ‘One China’. In his meeting with Khadka in Beijing on August 10, the Chinese foreign minister conveyed his country’s position on Taiwan and sought Nepal’s support.

According to China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Wang stressed on joining hands with other countries to “oppose US interference in China’s internal affairs”. In the meeting, Khadka reiterated Nepal's unwavering commitment to the One China Policy and assured that the Nepali territory will not be allowed to be used for any activity against China.

Beijing has reason to doubt Kathmandu’s commitment though, particularly after the parliament ratified the American Millennium Corporation Challenge (MCC) compact despite Beijing’s objection.

The formation of a government probe panel to study China’s alleged border encroachment and Nepal’s ‘pro-Western’ position on the Russia-Ukraine war have added to the suspicions of the northern neighbor.

Nepal has its own reasons to question China’s intent. Chinese overblown reaction to Nepal’s decision to ratify the compact was unbecoming of a good friend. Kathmandu is also displeased with Beijing for restricting the movement of goods across China-Nepal border points, citing Covid restrictions.

China’s claim that the West is fueling anti-China activities through Tibetan refugees in Kathmandu and its decision to engage only Nepal’s communist parties have also not gone down well with PM Deuba and his Congress party.

Upendra Gautam, general secretary of China Study Center Nepal, says the government lacks a clear vision and assertiveness to deal with China and other powers.

“The Deuba government seems to have realized that now,” he says. “Let’s hope Foreign Minister Khadka’s visit is not just a ritual.”

Gautam says big powers always want small countries like Nepal on their side. “The important thing is that we assert ourselves and clearly explain the fundamentals of our foreign policy.”

Besides clearing the air with Beijing, Khadka’s visit is also aimed at sending the message that Nepal is not taking sides and wishes for balanced relations with all powers.

China too has been trying to convince Nepali political parties, particularly the ruling Congress, that it is not partial towards communist forces.

During his Nepal trip, Liu Jianchao tried to convince Congress leaders that China’s Nepal policy is not guided by ideology.

Speaking on Khadka’s China visit, Chinese Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Hua Chunying on August 5 said: “China looks forward to strengthening strategic communication, cementing mutual support, and constantly promoting strategic partnership for development and prosperity.”

Subedi, the advisor to Deuba, says there could be progress on some bilateral projects after the visit. “We want to enhance economic cooperation with China,” he adds.

China is pushing for the implementation of some projects under the Belt and Road Initiative. Chinese officials are also concerned over the implementation of the pacts reached between the two countries during the 2019 Nepal visit of President Xi Jinping.

On August 10, Khadka and his Chinese counterpart Wang Yi held bilateral talks in Shandong, an eastern province of China.

According to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the two sides had cordial and fruitful meetings which took stock of all aspects of Nepal-China relations and agreed to promote cooperation in the areas of mutual interests.

In the meeting, both foreign ministers expressed their commitment to the timely implementation of the agreements signed and the understanding reached during high-level visits in the past. China announced that China will carry out the feasibility study of the Keyrung-Kathmandu railway under grant assistance.

We have raised all the issues related to China including the border, supply of goods, and other issues, said official requesting anonymity. During the meeting, according to the official, the Nepali side reiterated its position on One-China.

As the two neighbors appear to move towards a rapprochement, more high-level exchanges are on the cards, with CPN (Maoist Center) Pushpa Kamal Dahal likely to visit China next month.

Where will Nepal sell its excess energy?

Nepal will soon become a net energy exporting country in South Asia, behind only Bhutan.

Nepal already generates surplus electricity in the summer and the state power utility, the Nepal Electricity Authority, has been exporting 364 MW to India on a daily basis. With the 456 MW Upper Tamakoshi Hydropower Project likely to come online after two years and several other projects also in the pipeline, Nepal will soon become a round-the-year energy-surplus country.

For now, India is Nepal’s sole energy market but there are other several prospective markets in South and Southeast Asia. Energy-hungry Bangladesh is one. Many Bangladeshi companies are eager to invest in Nepal’s hydropower but are unable to do so due to a lack of legal framework.

This is where the Bilateral Investment Protection Agreement (BIPA) comes in, says Sunil KC, CEO of the Asian Institute of Diplomacy and International Affairs (AIDIA). “It will pave the way for Bangladeshi companies to invest in Nepal’s hydropower and take electricity to their country.”

Bangladesh has already proposed a draft agreement, with the proposal of importing 9,000 MW electricity from Nepal by 2040.

India, which was previously reluctant to allow Nepal to use Indian transmission infrastructure to export electricity to third countries, has also agreed to support Nepal’s energy trade.

India’s Central Electricity Authority still bars power trading from a Nepali company with Chinese investment.

But during Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba’s India visit in April this year, Nepal and India came up with a joint energy vision, agreeing to expand energy cooperation to include a third country under the framework of BBIN, a SAARC’s sub-regional grouping comprising Bangladesh, Bhutan, India and Nepal. They also pledged to develop cross-border transmission infrastructure and joint power generation projects, as well as to ensure two- way power trade —in what was a breakthrough in cross-border electricity trade.

Earlier last year, former Indian foreign secretary Harsh Vardhan Shringla had also said that India was taking the lead to promote a regional approach to energy cooperation.

But many doubt India will follow through on the agreement. They reckon India will not facilitate the sale of energy produced in Nepal in India or in Bangladesh for that matter.

Former Energy Minister Dipak Gyawali is not hopeful India will help Nepal sell electricity to Bangladesh.

“We must instead devise a policy of using the produced electricity within the country,” he says.

The former energy minister sees flaws in Nepal’s export-oriented approach to energy.

KC, of AIDIA, disagrees. There is no need to heed conspiracy theories that India will neither buy Nepal’s electricity nor allow its export to third countries.

The fact remains that Nepal alone will not be able to consume the electricity generated by its hydropower plants. “There is still going to be surplus energy to sell,” says KC.

Power export is also vital for Nepal to achieve the desired level of economic growth. Some energy experts say Nepal could in the long run devise a policy of utilizing electricity to fulfill its domestic needs. But for now there is no alternative to exporting energy to India and beyond.

Sushil Pokhrel, managing director of Hydro Village Pvt Ltd, sees China as another viable energy market. He says hydropower companies and government officials are currently doing homework to open a line for energy trade with China via the Rasuwagadhi border point.

For Nepal, ensuring an energy market in China is also important because India has made it clear that it will not purchase electricity produced by Chinese companies or from projects with Chinese components.

Government sources say Nepal has asked potential Chinese investors to explore the market for Nepali energy in their country.

Only a few weeks ago, Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba had also said that India would not buy electricity produced by Chinese companies. So before Chinese companies are given the right to build hydropower projects in Nepal, the government wants to ensure the viability of the Chinese market.

Regional bodies like the SAARC and the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC) have also taken initiatives for regional energy trade. Hence there is a prospect for regional energy trade beyond India and Bangladesh.

For instance, the SAARC Framework Agreement on Energy Cooperation (Electricity) was signed during the 18th SAARC Summit (Kandu, 26-27 November 2014) and later ratified by all SAARC countries..

But as the SAARC is in a dormant state over India-Pakistan disputes, energy cooperation among member states remains a distant dream.

There is hope from BIMSTEC though. In April 2020, a meeting of the energy ministers from its member countries approved the establishment of BIMSTEC Grid Interconnection Coordination Committee (BGICC). They also decided to seek Asian Development Bank’s help in preparing a master plan and directed the BIMSTEC Expert Group on Energy to develop a comprehensive plan on energy cooperation.

Energy Minister Pampha Bhusal says the BIMSTEC route could unlock the regional energy market for Nepal.

“It will benefit both Nepal and the region by reducing non-renewable energy generation and paving the way for an energy-sustainable future,” she says.

Nepal could potentially lose billions of dollars if it fails to export electricity to India and Bangladesh. But Bhusal is optimistic.

“India still relies a lot on energy from coal,” she says. “Electricity from Nepal can help it phase out dirty energy sources and switch to cleaner and greener ones.”