The race for new PM heats up in Nepal

Nepal Congress(NC) has emerged as the largest party from the Nov 20 elections. CPN-UML, CPN (Maoist Center) and Rastriya Swatantra Party(RSP) are set to emerge as the second, third and fourth largest parties respectively. Likewise, pro-royalast Rastriya Prajatantra Party (RPP) has revived its position in the national parliament under the leadership of Rajendra Lingden. Janata Samajbadi Party and Loktantrik Samajbadi Party, two big Madhes-based parties, didn’t fare well. The Election Commission(EC) has not made the official announcement of the result but an intra- and inter-party race for the new prime minister has already begun. Inside NC, senior leader Ram Chandra Poudel and youth leader Gagan Kumar Thapa have staked their claim to the post. While incumbent Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba has not responded regarding their intention, his core supporters do not think there is a leader who could replace him inside the party. Once the EC makes election results out, the party will hold the election of its parliamentary party leader. The winner will be eligible to become the party’s prime ministerial candidate. The concrete discussion on power-sharing deals with other coalition partners begins only after the NC settles its intra-party issues, as youth leaders like Thapa are saying that they are not in favor of continuing the coalition just for the sake of it. Instead, they are calling for a new power-sharing deal guided by common policy. Unlike in the NC, UML Chairman KP Sharma Oli and Maoist Center Chairman Pushpa Kamal Dahal do not have any challenges from within. Still, the government formation process is likely to become a sticky affair, following the fragmented vote in the elections. Weakened positions of major parties and the emergence of the new party like the RSP mean there is no telling how the new government composition will be. While top leaders of the major current coalition have already started parleys to explore the possibility of continuation of the present coalition, the UML wants to break it. Some UML leaders are openly proposing the NC to seriously consider the possibility of a NC-UML coalition government. It is hard to predict how the power-sharing deal pans out. Parties may not be able to forge a consensus on government leadership even after the EC announces the final election results. On Nov 24, UML Chairman KP Sharma Oli rightly pointed out that formation of a new government is going to be difficult, and even more so ensuring its sustainability. The NC will naturally stake its claim to the leadership of the next government. This, even though Deuba and Dahal had reportedly reached an understanding that the latter will get to become the next prime minister. It was part of the deal brokered by the two leaders to forge an electoral alliance to defeat the UML. But, with the Maoists failing to win enough seats in parliament, Deuba may not honor that pact. The NC-led five-party electoral alliance will require at least 138 seats to form a government. But due to poor performance of its members, the current coalition will struggle to string together a majority. They will most likely have to reach out to the parties like the RSP, RPP, fringe Madhes-based parties and independent candidates. And while the strength of the Maoist party may have reduced, it could still become the kingmaker. Without Maoists’ support, there won’t be a majority—neither for Deuba, nor for Oli. While Deuba may agree to hand over the government leadership to Dahal to prevent the UML from coming to power, it will be a very difficult task to say the least. UML won parliamentary seats nearly on par with the NC. The party’s chair, Oli, is the undisputed candidate for PM. There are murmurs that there is a chance of the UML and the Maoists coming together to form a government. Oli has already called Dahal offering a power-sharing agreement, even though the two leaders have not been seeing eye- to-eye after the bitter breakup of the erstwhile Communist Party of Nepal (CPN) in 2021, which was formed as a result of the merger between UML and Maoists in 2018. But with both Oli and Dahal claimants to the post of prime minister from their respective parties and their already fractious relationship, it is hard to imagine if and how they will come together to form a government. The NC-UML coalition government cannot be ruled out either. Oli had hinted about its possibility before the elections as well. And if the two parties were to come together, the fringe parties could lose their bargaining power. It could also bring some semblance of government stability. However, the last time the NC and UML entered a coalition, it had ended disastrously. After the 2013 second Constituent Assembly polls, the two parties had come together to form a government under a gentleman’s understanding that the NC would hand over the government reins to the UML after the promulgation of constitution. But the NC reneged on the promise and the UML went on to ally with the Maoists. Even if the NC and UML were to join hands to form a new government, the billion-dollar question remains: who gets to become the prime minister? No matter how far-fetched it may seem, there is a chance that Deuba and Oli could agree to lead the government on a rotational basis, considering that the emergence of new parties is a common threat to them. And if all fails, formation of a minority government also cannot be fully ruled out. In this case, the new government will have to take a vote of confidence within a month. None of the above-mentioned alternatives can be ruled out, because coalitions are never formed on the basis of ideology. Similarly, the power-sharing deal in the seven provinces will also influence the makeup of the government at the center. The issue of which party gets president and speaker is likely to become equally prickly in the overall power-sharing process. At the same time, the role and influence of external power is another factor that could determine the power-sharing deal. The fragmented parliament provides spaces to external powers to influence the formation process. Make no mistake, New Delhi, Beijing and Washington have already started exerting their influence in the government formation process.

Split vote complicates government formation in Nepal

The government formation process is likely to become a sticky affair following the fragmented vote in the Nov 20 parliamentary elections. Weakened position of major parties — Nepali Congress, CPN-UML, and CPN (Maoist Center) — and the emergence of the new party like Rastriya Swatantra Party (RSP) mean there is no telling how the new government composition will be. Had the Maoists won around 40-50 seats, its leader Pushpa Kamal Dahal was expected to lead the new government as a continuation of the current five-party coalition. But as the vote counting in 165 constituencies under the first-past-the-post (FPTP) reaches final stage it appears that Dahal’s party will only win around 30 seats in federal parliament. The Congress and UML could secure in between 80-90 each. Similarly, the RSP could get around 20 seats and the Rastriya Prajatantra Party (RPP) around 10. It means the new parliament will be more fragmented than it was in 2017. In this context, it is hard to predict how power-sharing deal pans out. The coming period of government formation will likely to prove long and hard. Parties may not be able to forge a consensus on government leadership even after the Election Commission announces the final election results, possibly in another two weeks’ time. On Nov 24, UML Chairman KP Sharma Oli rightly pointed out that formation of a new government is going to be difficult, and even more so ensuring its sustainability. The NC will naturally stake its claim to the leadership of the next government. This, even though NC’s Deuba and Maoists’ Dahal had reportedly reached an understanding that the latter will get to become the next prime minister. It was part of the deal brokered by the two leaders to forge an electoral alliance to defeat the UML. With the Maoists failing to win enough seats in parliament, Deuba may not honor that pact. Many NC leaders do not want the Maoists to lead the government anyway. The NC-led five-party electoral alliance will require at least 138 seats to form government. But due to poor performance of its members, the current coalition will struggle to string together a majority. The will most likely have to reach out to the parties like the RSP, RPP and fringe Madhes-based parties. And while the strength of the Maoist party may have reduced, it could still become the kingmaker. Without Maoists’ support, there won’t be a majority—neither for Deuba, nor for Oli. While Deuba may agree to hand over the government leadership to Dahal to prevent the UML from coming to power, it will be a very difficult task to say the least. The NC is a divided house when it comes to the prime ministerial candidates. Party leaders like Gagan Kumar Thapa and Ram Chandra Poudel have been angling for the post of prime minister. Deuba’s rival Shekhar Koirala has not spoken anything about it. There is also a strong voice inside the NC that the party should lead the government. UML which has won election at par with NC is a natural claimant to lead the next government. Oli has already called Dahal for a possible power-sharing agreement, even though the two leaders have not been seeing eye- to-eye after the bitter breakup of the erstwhile Communist Party of Nepal (CPN) in 2021, which was formed as a result of the merger between UML and Maoists in 2018. With both Oli and Dahal claimants to the post of prime minister and their already fractious relationship, it is hard to imagine if and how they will come together to form a government. The NC-UML coalition government cannot be ruled out either. Oli had hinted about its possibility before the elections as well. And if the two parties were to come together, fringe parties could lose their bargaining power. It could also bring some semblance of government stability. However, the last time the NC and UML entered a coalition, it had ended disastrously. After the 2013 second Constituent Assembly polls, the two parties had come together to form a government under a gentleman’s understanding that the NC would hand over the government leadership to the UML after the promulgation of constitution. But the NC reneged on the promise and the UML went on to ally with the Maoists. But even if the NC and UML were to join hands to form a new government, the billion-dollar question remains: who gets to become the prime minister? No matter how fart-fetched it may seem, there is a chance that Deuba and Oli could agree to lead the government on a rotational basis, considering that the emergence of new parties is a common threat to them. And if all fails, formation of a minority government also cannot be fully ruled out. In this case, the new government will have to take a vote of confidence within a month. None of the above-mentioned alternatives can be ruled out, because coalitions are never formed on the basis of ideology. The result of provincial assembly will also shape the possible power-sharing in the center. At the same time, the role and influence of external power is another factor that could determine the power-sharing deal. The fragmented parliament provides spaces to external powers to influence the formation process. The race for the next prime minister has begun.

What are the new prime minister’s biggest challenges?

If parties do not prolong the power-sharing deal, Nepal will get a new government within a month. But the next dispensation is unlikely to enjoy a full five-year term as the election is all set to produce a hung parliament. Whosoever becomes the new prime minister faces multiple challenges, both at domestic and external fronts. The foremost challenge will be getting the faltering economy on track. Soaring interest rates, inflation, dwindling foreign exchange reserves, and effects of import ban have battered the economy. Fear of economic recession looms large. The first order of business for the new prime minister should be appointing a finance minister who can rescue the economy. He must get someone who is actually qualified for the job, not a party loyalist. The next step would be to revive people’s trust in key state institutions, such as parliament, judiciary, and constitutional bodies. The basic democratic tenet of check-and-balance has been shaken by overt politicization of state organs. The judiciary is without a full-fledged chief justice, as an impeachment motion is pending against the disgraced high office-holder, Cholendra SJB Rana. The damning exposé on Rana’s political ambition whilst leading the Supreme Court has eroded public trust in the judiciary. Rebuilding the court’s image and its legitimacy will take hard work and a long time. The new prime minister will also have to find a way to work with a hung parliament. Over the last five years, the parliament was not allowed to function independently. The leadership of the legislative body acted on the whims of political parties, and as a result, failed to endorse important bills. The neutral role of the speaker came into question in many instances. Like in the past, the new parliament should not act as a rubber stamp of certain political parties. Again, it will be incumbent on the executive to ensure this. All laws should be formulated by an elected legislative body, not through ordinances. Preventing corruption is another challenge for the new prime minister. To do so, the incoming government and its partners should allow the Commission for the Investigation of Abuse of Authority to function independently. The commission has consistently failed to deal with large-scale corruption cases, largely due to political pressure. It will be the job of the next government to allow the anti-graft body to do its work without any hindrances. On the external front, there are many challenges the new prime minister and his government must deal with to navigate the increasingly rough waters of geopolitics. In their election manifestos, all major political parties have pledged to adopt a balanced relationship with India, China, and the US. This is easier said than done. The new prime minister should be able to tell these major powers that there is a redline that they should not cross while dealing with Nepal. But before taking on the aforementioned tasks, the new prime minister should keep his party in order. Since 1990, all prime ministers have faced more hostility from within the party than the opposition party. A recent example was the downfall of the KP Sharma Oli-led government due to intra-party disputes. Managing the conflicting interests of coalition partners is key to yielding results for the next prime minister. It will take genuine effort—all the more so because the people’s belief in political parties and the system is declining. This time there is an additional challenge too—accommodating the voices and interests of new political forces—Rastriya Swatantra Party, some independent candidates and Janamat party-led by CK Raut. Many of them want to make changes to the 2015 constitution, which could divide the House. The new prime minister has a rocky road ahead.

Why did Nepal see low voter turnout this time?

Nepal’s Nov 20 parliamentary and provincial assembly elections registered a voter turnout of 61 percent, according to the Election Commission (EC). Speaking at a press conference, Chief Election Commissioner Dinesh Thapaliya said voter turnout fell below expectations. The highest turnout (78 percent) was recorded in the second Constituent Assembly (CA) elections in 2013, while the lowest was in the parliamentary elections of 1993 (61 percent) and the first CA election in 2008 (61percent), respectively. In the 2017 parliamentary and provincial assembly elections, the turnout of voters was decent at 68.67 percent. In the local-level elections held in May this year, voter turnout was 66.86 percent. Voter turnout this time, however, was much lower, even though there were no major security threats to the elections. In 2017, people were excited to vote because they had hoped the elections would lead the country toward political stability and prosperity. But that was not to be. Some analysts say the post-2017 political scene was the very reason why many voters did not cast their ballots this time. Chandra Dev Bhatta, a political analyst, says lower turnout was expected right from the very beginning when major political parties country began allocating tickets. The parties distributed election tickets to their near and dear ones, as they had been doing since the 1990s. Many candidates were familiar faces who even after winning the elections had delivered little, if nothing, to their constituencies over the last three decades. “The voters, irrespective of their age and political persuasion, this time wanted to see new candidates who could bring about real change,” says Bhatta. “But that didn’t happen when the parties announced their candidates.” Another reason for low voter turnout, says Bhatta, was the fact that the election this time was not conducted on any specific agendas, ones connected to the livelihood of the people. “Major parties tried to trump up the rumor that if they didn’t win the election this time, the country’s democracy, sovereignty, and the constitution itself would be endangered,” says Bhatta. “Of course, the discerning voters didn’t buy this bluff.” In fact, declining voter turnout is a global trend. According to a study carried out by IDEA International in 2016, despite the growth in the global voter population and the number of countries that hold elections, the global average voter turnout has decreased significantly since the early 1990s. Global voter turnout, says the report, was fairly stable between the 1940s and the 1980s, falling only slightly from 78 percent to 76 percent over the entire period. “It then fell sharply in the 1990s to 70 percent and continued its decline to reach 66 percent in the period of 2011–15.” This is most definitely not because the voters are not interested in politics. Analysts say it is perhaps because voters no longer identify with their politicians. Voter turnout in the previous elections 1991: 65.15 percent 1993: 61.86 percent 1999: 65.79 percent 2008: 61.7 percent (FPTP) and 63.3 percent (PR) 2013: 78.74 percent (FPTP), 79.82 percent (PR) 2017: 68.67 percent 2022: 61 percent

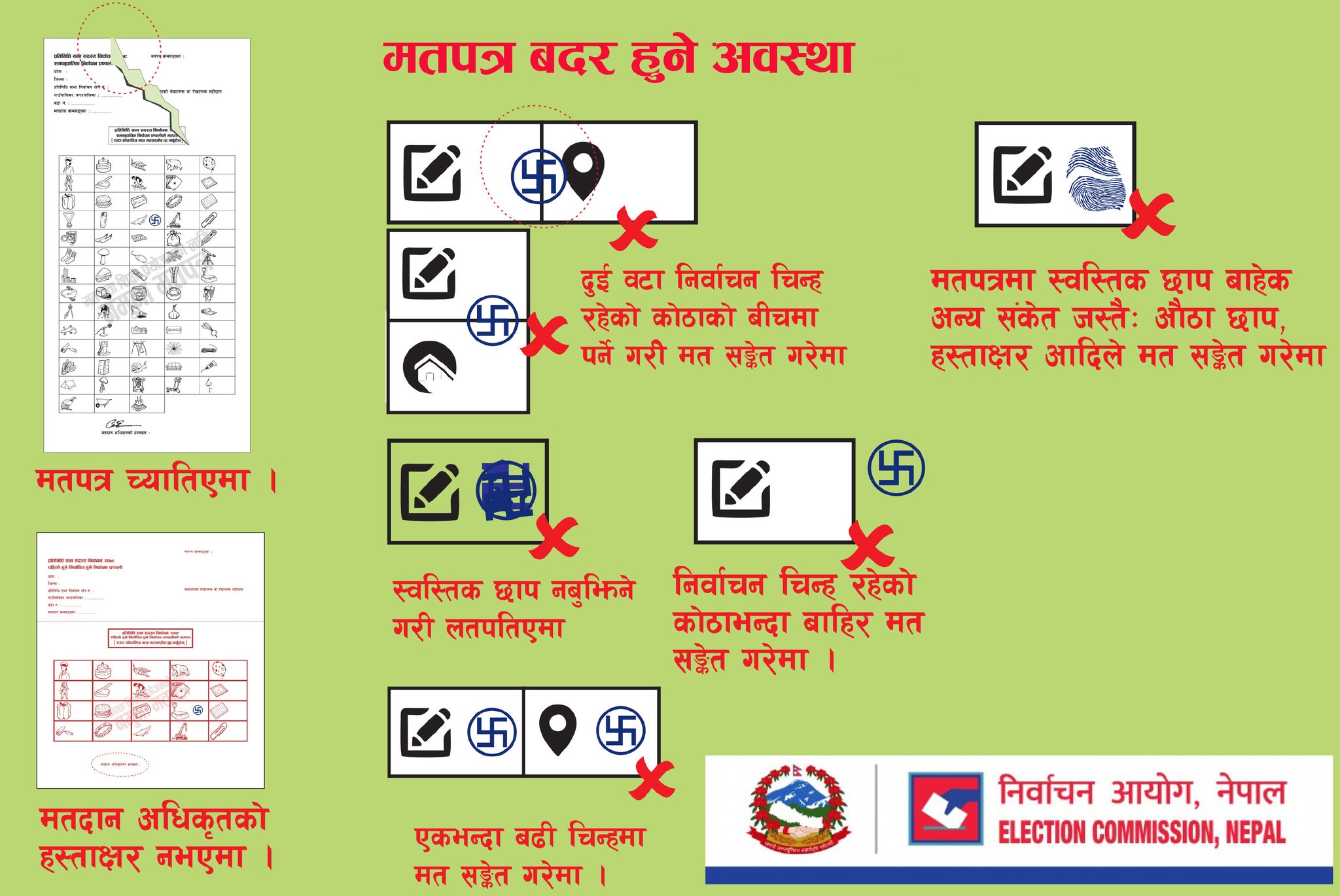

Increasing invalid votes cause for concern

Over the past three-decade, there has been a sharp increase in political awareness among Nepali citizens. This is largely due to rapid expansion of information technology. But there is a contradiction when it comes to the information related to elections. Despite the voter education campaign launched by the Election Commission (EC), the number of invalid votes has been increasing. In the 1991 parliamentary election, the first one after the restoration of democracy, the number of invalid votes was 2.75 percent of the total vote cast. In the 2017 national elections, there was a sharp rise in invalid votes at 14 percent (see chart). There is a concern that the number of void ballots could go up in the November 20 elections. Former election officers and political analysts attribute various factors behind the high number of votes getting disqualified. Invalid votes went up mainly after the 2017 local and parliamentary elections, first polls conducted under the federal set-up. One reason behind the high number of invalid votes in 2017 could be that voting for the federal parliament and provincial assemblies took place on the same day. The number of ballot papers increased, and, as a result, many voters were confused. And it was not just in rural areas where the invalid ballot numbers were high; many urban votes and those particularly those cast in the Madhes province failed to qualify for count. Similarly, in the local elections held in May this year, the ratio of invalid votes was higher in key metropolitan cities than in the hill and mountain region. For the upcoming polls, too, the EC has finalized four ballot papers and separate ballot boxes. Any small mistake while stamping the ballot or dropping the ballot could make it invalid. Another reason behind increasing invalid vote numbers could be electoral alliances among many parties. Dolakh Bahadur Gurung, former election commissioner, says while there is no one single reason behind the increasing number of invalid votes, poll alliances among multiple parties could be one. “Poll alliances have definitely left the voters in a quandary,” he says. Gurung suggests making the voter education campaign more effective and result-oriented to reduce the number of invalid votes. Billions of rupees are being spent in the name of voter education, but the results remain dismal. The election body hasn’t been able to reach out to all voters. When its officials reach the doorsteps of voters, in most cases, most family members are out in their jobs. And in the case of rural voters, they are working in their fields. Similarly, the Election Commission has also failed to clearly explain the voting process to voters. Meanwhile, political parties are also creating confusion among voters by focusing their voter education drive on how to vote for their candidates. Gurung says after 2017, there has also been an emergence of a new trend, where grassroots party cadres who are unhappy with the electoral alliance intentionally cast invalid votes instead of just abstaining from voting. The lack of electoral laws giving voters the option to reject all candidates if they do not like any of them is also contributing to invalid votes. Gurung says the NOTA (none of the above) option on ballot papers can fix this problem. NOTA enables voters to officially register a form of protest over the candidate-selection process. People who do not want to vote for any of the candidates are likely to intentionally cast invalidate votes. “The against-all voting option can resolve this problem,” says Gurung. It has been eight years since the Supreme Court’s order to implement the NOTA option, but major parties are reluctant to do so. Following the court’s order, the EC in 2016 had incorporated this provision in the drafts of the election-related laws. But the parties opted to remove it after parliamentary deliberations in 2017. If such provisions are made, the number of NOTA , which is a basic democratic right, may increase, but it will also reduce the invalid votes, says Pradip Pokhrel, an election expert. “Increasing invalid votes could be a reflection of people’s frustration that they do not want to vote for any candidates fielded by the political parties,” says Pokhrel. “The same old faces have been contesting the elections since 1990, and there is a growing resentment among the voters.” Another way to reduce invalid votes could be the introduction of an electronic voting machine (EVM). But again political parties are against it. In the previous elections, the EC had launched EVMs in some constituencies, but it was opposed by political parties, claiming that the machines could be rigged. Gurung disagrees with the parties. “The use of EVM will be cost- and time-efficient. It will also grant voting rights to those Nepali living abroad.” Invalid votes 1991: 4.42 percent 1993: 3.16 percent 1999: 3.16 percent 2008: 6 percent 2013: 4.96 percent 2017: 14 percent

Foreign policy challenges of new government

Issues related to foreign policy didn’t find much space during the election campaigns of major parties this time. Save the matter of map row with India, for which KP Sharma Oli of CPN-UML and Pushpa Kamal Dahal of CPN (Maoist Center) are competing to take credit for, all political parties are fundamentally on the same page when it comes to foreign policy. Only their priorities differ. This could be because the November 20 election is highly unlikely to produce a single-party majority government. Even big parties like Nepali Congress (NC) is contesting for only 91 seats under First-Past-the-Post (FPTP) category to create space for its four other electoral allies including Maoist Center. The main opposition, CPN-UML, which is fighting alone in most constituencies, is competing for over 140 seats. So, with a hung parliament the most likely scenario, parties are expected to cobble together a coalition government, led either by Sher Bahadur Deuba of Nepali Congress, Dahal of Maoist Center, or even Oli of UML. Who will become the next prime minister depends on how the power-sharing deal among the ruling five-party alliance pans out. With a coalition government in place, there is sure to be disagreement on Nepal’s foreign policy. If there is a government of NC and communist parties like Maoist Center, there will certainly be friction concerning ties with China. Congress, for one, stands against taking loans under China’s Belt and Road Initiatives (BRI) to finance infrastructure projects. In its party manifesto, Deuba’s party has also mentioned about the border dispute with China in the Humla district. A leftist party like Maoists, or UML for that matter— considered close to China—are unlikely to support NC in this regard. Both parties dismiss the alleged border dispute with China. So, it is going to be an uphill task for the coalition government to forge a consensus on how to deal with these issues. On issues related to India, NC and Maoists have different opinions. The Maoist party wants to push the agenda of the 1950 Peace and Friendship Treaty, though it has substantially eased its stance after joining the peace process in 2006. Still, the two parties have many other issues with India, where they do not see eye to eye, mainly due to their different ideological positioning. Similarly, while the Maoists and UML may have almost the same position on dealing with India on contentious bilateral issues, the former has a more anti-US posture. In their election manifestos, the two parties have repeated the same issues, such as maintaining a balanced ties with both India and China and sticking to non-aligned foreign policy. They however fall short of mentioning how they plan to deal with growing geopolitical tensions between China and the US. The next government will have a tough time maintaining blanched ties with China and the West. Chinese president XI Jinping, who has been elected for the third term, will likely adopt an even more aggressive posture in his neighborhood policy. Meanwhile, the US is set to expand its military and economic leg of its Indo-Pacific Strategy (IPS) in Nepal as a counterweight to growing Chinese influence in Nepal and much of South Asia. Of late, India, too, is growing wary of the American and Chinese influence in Nepal. Sources say New Delhi is desperate to revive its political influence in Kathmandu, which dwindled after 2018. Sanjay Upadhya, a US-based foreign affairs expert, says the challenge for the next government will be to manage relations within the increasingly unstable triangle of India, China and the US. NC has promised to engage with India and China diplomatically to address border-related disputes, while UML has injected greater rhetorical flourish in its intention to bring back Kalapani, Lipulek, Limpiyadhura and other territories. These are not easy issues, and the ruling and opposition parties will have the responsibility not to politicize the commitments based on domestic compulsions and conveniences, says Upadhya. Within this core challenge, he says Nepal will also have to focus on other issues, such as revitalizing the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) for genuine collective self-reliance. There is also the imperative of grasping Nepal’s convergences and divergences from the experiences of neighbors like Pakistan, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka. Upadhya says it would be helpful to learn from those countries’ experiences on how best to navigate through the waters of international relations that are likely to become choppier in the days ahead. Pursuing economic and cultural diplomacy are all challenges that depend on the political stability Nepal could generate after the elections. Binoj Basnyat, strategic affairs analyst, says one challenge that the next government could confront is to convince the donor of national strategic benefits. Insufficiently defined national foreign policy will swing the big powers interests to prevail through weak political postures as well as political parties to remain in power, he says. Basnyat is of the view that foreign policy approach will be different with the new administration in Nepal.

Elections will make politics more unstable

Nepal has conducted seven parliamentary elections since 1959. But the upcoming election will be a historic one, in that it is the first to be held after the completion of parliament’s term. But as far as historic significance goes, that’s about it. The first parliamentary election of 1959 paved the way for the formation of a bicameral legislature comprising upper and lower houses of parliament. That election, the Nepali Congress won the most seats (74) and its leader BP Koirala formed a government. The then Communist Party of Nepal came a distant fourth with just four seats behind the then Nepal Rastrabadi Gorkha Parishad and Samyukta Prajatantra Party. But the people’s elected government was short-lived, as the then king Mahendra wrested power from it and imposed the partyless Panchayat regime. After the restoration of democracy in 1990, the NC once again came to power through the 1991 general election. The main communist force, the CPN-UML, came a distant second. Since then, all elections have essentially been a two-horse race between the NC and communist parties. This is despite the emergence of new political forces, such as Maoist and Madhes-based parties, after 2006, and the start of alliance politics with the 2017 elections. The Nov 20 elections can be termed a direct contest between two sides because all major parties are contesting by forming two distinct alliances, one led by the Congress and another by the UML. The members in the NC-led electoral alliance or the so-called democratic left alliance are the CPN (Maoist Center), CPN (Unified Socialist), Janata Samajbadi Party Nepal and Rastriya Janamorcha. The UML, meanwhile, leads the second alliance, and its members are the Upendra Yadav-led Janata Samajbadi, the royalist Rastriya Prajatantra Party and other smaller parties. Bhojraj Pokharel, former chief election commissioner, says political parties are yet to get a full maturity, which means the capability to avoid provocation, develop more understanding and engage in logic-based decision-making. “Nepali political parties should first institutionalize themselves which means intra-party good governance, collective leadership, less factions and interest groups.” It was due to the lack of intra-party democracy that former prime minister and UML chair KP Sharma Oli dissolved parliament twice. Analysts say as long as intra-party democracy is lacking and several parties are running the government with their own set of interests and agendas, Nepal cannot achieve political stability. They reckon the November 20 elections too won’t deliver a stable government, as more than two parties are set to form the next government. An agreement between either NC and Maoist or UML and Maoist to lead the government on equal terms could sow the seeds of instability. Political analyst Bishnu Dahal says, as a single party getting the majority votes is slim, Nepal is on the course of yet another period of political instability. “In previous elections, political stability at least used to be one of the planks of parties. This time, they themselves have planted the seeds of instability,” says Dahal. 1959 election Total seats: 109 Nepali Congress: 74 Nepal Rastrabadi Gorkha Parishad: 19 Samyukta Prajatantra Party: 5 Communist Party of Nepal: 4 Nepal Praja Parishad(Mishra): 1 Nepal Praja Parishad(Acharya): 2 Independent:4 1991 elections Total seats: 205 Nepali Congress: 110 CPN-UML: 69 Sangyuta Jana Morcha: 9 Nepal Sadbhawana Party: 6 Rastriya Prajatantra Party(Chand):3 Nepal Majdoor Kishan Party: 2 Nepal Communist Party(Pragatishil): 2 Rastriya Prajatantra Party(Thapa): 1 Independent: 1 1993 elections Total seats: 205 CPN-UML: 88 Nepali Congress: 83 Rastriya Prajatantra Party: 20 Nepal Majodoor Kishna Party: 4 Nepal Sadbhawana Party: 3 Independent: 7 1999 elections Total seats: 205 Nepali Congress: 111 CPN-UML: 71 Rastriya Prajatantra Party: 11 Nepal Sadbhawna Party: 5 Sangyukta Jana Morcha: 5 Nepal Majdoor Kishan Party: 1 Independent: 0 2008: Constituent Assembly elections Total: 601 CPN (Maoist): 226 Nepali Congress: 110 CPN-UML: 103 Madhes Janadhikar Forum: 50 Tarai Madhes Loktantrik Party: 19 Sadbhawana Party: 9 (Note: The remaining seats were won by fringe parties; there were 24 political parties) 2013 Constituent Assembly Elections Total: 601 Nepali Congress: 197 CPN-UML: 174 Maoist: 79 Rastriya Prajatantra Party(Nepal): 24 Sanghaya Samajbadi Forum, Nepal: 15 Madhesi Janadhikar Forum(Loktantrik): 14 Rastriya Prajatantra Party: 13 Terai Madhes Loktantrik Party: 11 Sadbhawana Party: 6 CPN(ML): 5 Nepal Majdoor Kishan Party: 4 2017 Parliamentary Elections Total seats: 275 CPN-UML: 121 Nepali Congress: 63 CPN (Maoist Center): 53 Sanghya Samajbadi Forum: 16 Rastriya Janata Party Forum: 17 Rastriya Prajatantra Party: 1 Naya Shakti Nepal: 1

Satis Devkota: Unnatural coalition leads to political instability

Satis Devkota is an associate professor of economics and management at the University of Minnesota Morris. He holds a PhD in economics from Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan, US. He closely follows Nepal’s politics, economy and international politics. Devkota talks to Kamal Dev Bhattarai focusing on the Nov 20 elections. What is your take on Nepal’s growing culture of alliance politics? In a democratic society, people are free to create their political parties and contest in elections, which are free of coercion and fair to all contestants. However, forming a political alliance among a group of political parties with diverse political ideologies—political-economic philosophies—blunts the purity of our democracy. Such an alliance is unnatural, and a reflection of the incompetency or insecurity of political parties engaged in forming such an alliance. In general, a political alliance is a group of political parties that are formally united and working together if they have common aims. Looking at the past 30 years of political history in Nepal, you can find only a couple of political alliances that make perfect sense. Could you explain the culture of past alliances? First, the NC-Left front alliance that was formed in 1990 together fought against the autocratic Panchayat regime to establish the Westminster model of parliamentary democracy in Nepal. The shared objective was achieved, and the country’s multi-party democracy was reinstated after 30 years. Second, after King Gyanendra dissolved the parliament and seized power in Feb 2005, a seven-party alliance was formed that fought against the king’s direct rule with the intent to restore parliament and multiparty democracy. In the face of broad opposition, the king restored the previous parliament in April 2006. Again, the shared objective of forming the political alliance was met. Besides, let’s evaluate the provisions to form the government in the current constitution of Nepal. A coalition government could be an alternative if a single party cannot achieve the majority in parliament. So, forming a political alliance to form a coalition government is constitutional, and that might lead to political stability if our political parties are prudent and understand political ethics, and respect the values of politics. Unfortunately, our leaders and political parties are not on that boat. Forming a political alliance in the general election for the house of the representative and provincial election between the two major forces (socialist and capitalist) with the wider difference in ideology, political philosophy, and political-economic agendas is against the ethos of democracy and completely unnatural. It is entirely guided by a single objective: to size down the strength of CPN (UML) in parliament and the provincial positions and to stop KP Oli from being the prime minister again. Such an alliance is unacceptable in a flourishing democracy. The political leaders are guided by their egos rather than their social responsibilities. Will the Nov 20 elections ensure political stability? No. The recent public choice literature discusses various political features which crucially influence government behavior, and drive a wedge between what governments actually do and what they are advised to do by economists. Typically, when there is a coalition government led by a political alliance between the political parties with opposing ideologies, political power is dispersed, either across different wings of the government, or amongst political parties in a coalition, or across parties that alternate in power through the medium of elections. The desire to concentrate or hold on to power can result in political instability and inefficient economic policies. For instance, lobbying by various interest groups, together with the ruling party’s wish to remain in power, often results in policy distortions being exchanged for electoral support. Generally, politicians are interested solely in maximizing their probability of surviving in office, so the resulting character of government is pretty much unstable and very far away from the benevolence assumed by more traditional normative theories of government behavior. In addition, political parties are almost exclusively concerned with furthering the interests of their own support groups. Thus, the conclusions that follow from this discussion are very much different from the conclusion that can be reached if there is a stable government. During electioneering, all political parties commit to bringing the wave of development, but it is limited only to the slogan, what are the major hindrances to Nepal’s development? Political parties, their leaders, and policymakers lack a clear understanding of the determinants of growth and development in Nepal. Even though they know the common determinants, they may not internalize how each of those determinants affects growth and development, what strategies promote inclusive growth and sustainable development, and if that growth and development strategy leads to achieving the objective of a welfare state in the long run. Besides, political parties and policymakers do not have clear pictures of the intermediate and final outcomes of the long-run growth process. That creates confusion and policy dilemmas, which leads to misleading outcomes. Actually, policymakers have to look at the proximate and fundamental factors that affect the growth and development of a country. Capital accumulation and productivity growth are the proximate determinants of growth. In contrast, luck, geography, culture, and institutions are fundamental determinants of the growth and development of any country in the world, and Nepal is not exception. Understanding this fact and internalizing the channel through which each of those factors affect our growth and development is fundamental in the first place. That knowledge helps policymakers form evidence-based policies to achieve high growth, alleviate poverty, reduce inequalities, and promote all-faced development in the country. That says there is not just a single hindrance to growth and development in current Nepal. How does a coalition government affect good governance and service delivery? As I have mentioned earlier, a coalition government led by a political alliance of parties with opposing political views leads to political instability and forms an unstable government. That can be a cause of economic distortions. Unstable coalitions or governments that are not likely to remain in power for an extended period of time are liable to introduce policy distortions for at least two reasons. First, such governments obviously have very short time horizons that have important implications for economic policy in general and budgetary policy in particular. If political power alternates rapidly and randomly between competing political parties or groups of parties, then each government will follow myopic policies since it assigns a low probability of being relocated. Hard policy options whose benefits flow after a long gestation lag are unlikely to be adopted by such a government. Instead, it may spend indiscriminately in order to satisfy the short-term needs of its support groups. This will result in a legacy of high debt to its successor. Although this may constrain the actions of the next government, the current government does not care about the priorities of the next government. The second route through which the rapid turnover of governments may induce policy distortions is relevant in the case of coalition governments. The shorter the expected duration of such governments, the more difficult it will be for the ruling coalition members to agree on policies. Of course, the more heterogeneous the parties in the ruling coalition, the greater the lack of cooperation will be. Each party in the ruling coalition may then try to promote populist policies in order to exploit its own narrow interests. The most likely casualties of all this will be fiscal discipline, good governance, and service delivery.