In a U-turn, Dahal ditches Deuba to form government with Oli

There are no permanent friends or foes in politics. True to this statement, the CPN-UML and CPN (Maoist Center) stand at the cusp of forming a coalition government while the Nepali Congress has been bumped to the opposition aisle. In a dramatic turn of events, the Maoist Center on Sunday decided to part ways from the five-party alliance led by the NC and join the UML to form a new government. The two parties have agreed to lead a rotational government for 2.5 years each. Maoists chair Pushpa Kamal Dahal will hold the post of prime minister for the first-half of the government’s term, followed by UML chief KP Sharma Oli. As per the agreement, Dahal was appointed the new prime minister by President Bidya Devi Bhandari late Sunday afternoon. The Maoist Center and UML have also agreed to share the post of parliament speaker on a rotational basis. The post of president will be held by the UML for a full five-year term. “Now that we have agreed to form an agenda-based government, the remaining issue of power-sharing will be settled after the government formation,” said UML General Secretary Ishwar Pokhrel. Rastriya Swatantra Party, Rastriya Prajatantra Party, Janata Samajbadi Party, Janamat Party and Nagarik Unmukti Party will also join the coalition. Together, they will have 170 seats in the 275-member parliament. The NC remains the largest party with 89 seats. The UML and Maoists have 78 and 32 seats respectively. Until Sunday morning, the coming together of UML and Maoist Center was unexpected, given the bad blood between Oli and Dahal. Since the Maoists contested the Nov 20 general elections by forming an electoral alliance with the NC and three other fringe parties, it was widely believed that the five-party coalition would prevail. But Dahal abruptly abandoned the coalition ship saying the NC tried to ditch him by taking an “unrealistic condition” of taking both prime ministerial and presidential posts. “Just a week earlier, Deuba had agreed to form a rotational government, where I would lead until mid-term. But he reneged on the agreement,” said Dahal. “He (Deuba) told me that he was under extreme pressure from his own party leaders, that he could not convince them.” The Maoists chairman also said that it was never his intention to break the five-party coalition. “There was a new situation after Deuba decided not to honor the agreement,” he added. Maoist leader Barsha Man Pun had been working behind the scenes to plan for a contingency, in case the NC decides to play spoilsport. He had been holding meetings with the UML to discuss the possibility of forming a coalition government. On Saturday, Pun had said his party would break the coalition if it didn’t get the leadership of the new government. Inside the NC, Deuba was hard-pressed not to hand over the prime ministerial post to the Maoists. Some leaders even advised abandoning the Maoist party and forming a coalition government by bringing together other fringe parties. Clearly, the NC didn’t anticipate the prospect of Dahal patching things up with Oli. The UML and Maoists are once again returning to power, just like they did after the 2017 elections. The two parties merged to form the Nepal Communist Party (NCP) in 2018, only to break up less than three years later after Oli didn’t honor his promise to hand over the prime ministerial post to Dahal after 2.5 years. The rivalry between Oli and Dahal deepened over the years, as the NCP breakup was particularly hard on the UML, whose senior leaders Madhav Kumar Nepal and Jhala Nath Khanal also soon left the party to form CPN (Unified Socialist). Oli, who was leading the government at the time, tried unsuccessfully twice to dissolve the parliament to hold on to power, but was eventually ousted at the order of the Supreme Court. Oli was replaced by Deuba, who would lead a five-coalition government with the Maoists, Unified Socialist, Janata Samajbadi and Rastriya Janamorcha. These same five parties forged an electoral alliance in the Nov 20 elections. Since the elections, the UML has been sitting on the fence regarding the government formation process. It was biding its time for the five-party alliance to finally crack. Soon after the elections, the UML had said that it was ready to support the NC in the government formation process. But, at the same time, it was also holding closed-door negotiations with the Maoists. Despite the strained relationship between Oli and Dahal, the second-rung leaders from the two parties were in continuous talks to revive a coalition government led by leftist parties. In a way, things have come full circle for Oli and his party. Disagreement inside the same coalition that expelled the UML from power back in 2021 has become the reason why the party is now returning to power.

US expanding economic leg of IPS in Nepal

The US has been expanding its economic footprint in the Indo-Pacific region. In May, it launched the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) bringing 12 countries (40 percent of the world’s GDP) on board. The IPEF focuses on four key pillars: trade, supply chains, clean energy, and fair economy. The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) is at the forefront of implementing this framework, which is said to be the economic leg of the Indo-Pacific Strategy (IPS). Across the region, the US development agency has been implementing trade and competitiveness (T&C) programs. A report prepared by the agency in 2021 states that it is a whole-of-government program designed to incentivize greater business engagement in the Indo-Pacific region by enhancing trade facilitation, improving market-based trade and competitiveness laws and policies, and increasing private sector participation. The overall goal of T&C is to increase inclusive and broad-based sustained free and fair trade as well as competitiveness in the Indo-Pacific region. In September this year, USAID launched a T & C project, the first of its kind, in Nepal. USAID and the Ministry of Industry, Commerce and Supplies jointly launched the project. The ministry, however, has said it will only play the role of an advisor to the program, while stressing that it is not an implementation partner. “We cannot become a part of it but can facilitate the implementation of the project,” a senior ministry official told ApEx. He was apparently unaware of the fact that the project fell under the broader framework of IPS. Foreign policy expert Rupak Sapkota said great powers are implementing the projects of their strategic importance in an opaque manner. “In order to avoid potential backlash, they are pushing such strategies in the guise of economic benefit, development and job creation,” he added. According to Don McLain Gill, a Manila-based expert on Indo-Pacific affairs, the US initiative is crucial at least in theory, as there is a large infrastructure development gap in the region and the notoriety of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). “China’s disregard for international macroeconomic stability by funding unsustainable projects for countries with low or non-existing credit ratings eventually burdens them by pulling these countries deeper into debt burdens,” he told ApEx. “The potential alternatives provided by the US and its allies are a welcoming development.” This is not the first time the US or the West has pushed for a “game changing” alternative to China’s BRI. Such projects didn’t take off due to domestic constraints, which led to the inability of the US and its allies to provide the needed funds. Ultimately, said Gill, the US and its allies must come up with a more comprehensive and practical strategy that leverages on their strengths and expertise for the benefit of the developing world. “Presenting new initiatives year after year that are not fully funded, well-implemented, and quickly replaced may further tarnish the legitimacy and credibility of the West to provide robust platforms for growth amid China’s growing global ambitions,” he added. Since the launch of IPEF, the US has been briefing other South Asian countries, but no formal discussion has been held with Nepal. Bangladesh’s Foreign Minister AK Abdul said on Thursday that his country is looking into the pros and cons of the framework in order to decide whether it is beneficial to the country. IPEF is regarded as a counterweight against Chinese influence in the region. Last week, trade and economic ministers of all members of IPEF met to discuss economic issues including the digital economy. Though Nepal is not an official IPEF partner, observers say economic activities under the IPS are already taking place.

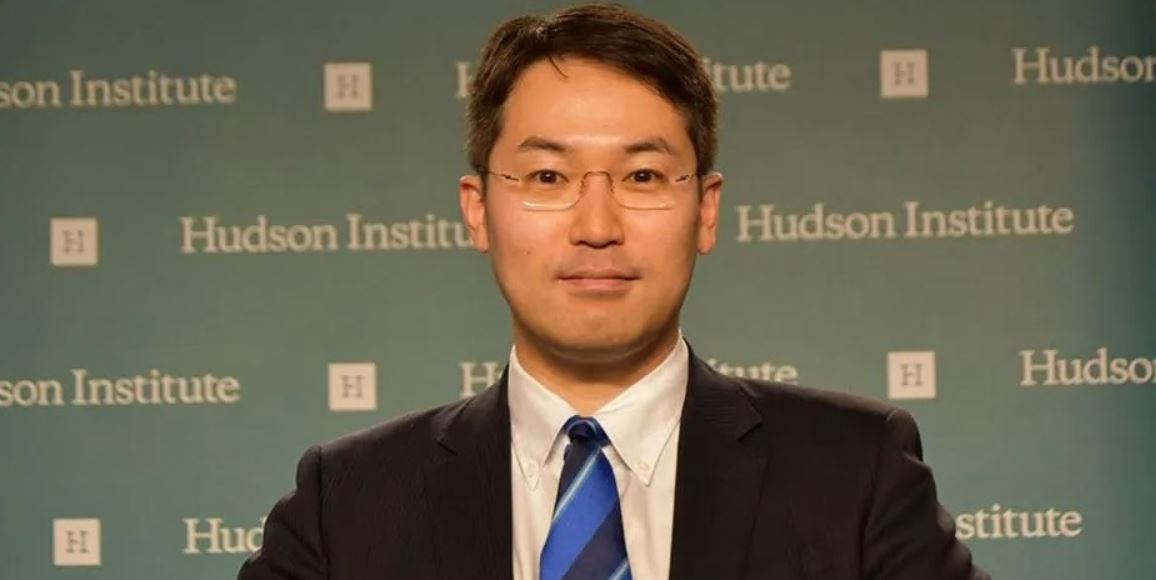

Satoru Nagao: Nepal should gradually distance itself from China

Satoru Nagao is a fellow (non-resident) at Hudson Institute, based in Tokyo, Japan. From Dec 2017 through Nov 2020, he was a visiting fellow at Hudson Institute, based in Washington, DC. Nagao’s primary research area is US-Japan-India security cooperation. He was awarded his PhD by Gakushuin University in 2011 for his thesis, ‘India’s Military Strategy,’ the first such research thesis on this topic in Japan. Gakushuin University is a premier institution from which members of the Japanese Imperial Family have also graduated. Kamal Dev Bhattarai talked to him about Japan’s new security policy, US-China contestation among others. Japan has come up with its new National Security Strategy, what could be its possible implications for the Indo-pacific region? This National Security Strategy changes Japan’s security strategy drastically, and its impact will spread to the Indo-Pacific region. There are three pillars in this strategy. Firstly, Japan clearly identifies China, North Korea, and Russia as threats to Japan in this document. Secondly, Japan will integrate strategies both military and non-military to deal with the threats. And thirdly, Japan will strengthen international cooperation to deal with China, which means like Australia and India, Japan will possess counter-strike capabilities. In some cases, Japan will commit an offensive-defense operation. The offense-defense combination with long-range strike capability is a more effective strategy than a defense-only strategy to counter China’s territorial expansion. Say, if Japan and India possess long-range strike capabilities, this combined capability makes China defend multiple fronts. Even if China decides to expand its territories along the India-China border, China still needs to expend a certain amount of its budget and military force to defend itself against Japan. This document clearly mentions that Japan will increase official development assistance (ODA) for a strategic purpose. For the purpose of deepening security cooperation with like-minded countries, apart from ODA for the economic and social development of developing countries and other purposes, a new cooperation framework for the benefit of armed forces and other related organizations will be established. It will affect the whole part of the Indo-Pacific. For a long time, a ‘hub and spoke’ system has maintained order in the Indo-Pacific. In this system, the hub is the US and the many spokes are the US allies such as Japan, Australia, Taiwan, the Philippines, Thailand, and South Korea in the Indo-Pacific. A feature of the current system is that it heavily depends on the US. For example, even though Japan and Australia are both US allies, there is no Japan-Australia alliance. However, China’s recent provocations indicate that the current system has not worked to dissuade its expansion. Between 2011 and 2020 China increased its military expenditure by 76 percent, and the US decreased its expenditure by 10 percent. Even if the US military expenditure were three times bigger than China’s, the current “hub and spoke” system would still not be enough As a result, a new network-based security system is emerging. The US allies and partners cooperate with each other and share security burdens with the US and among themselves. Many bilateral, trilateral, quadrilateral, or other multilateral cooperation arrangements—such as US-Japan-India, Japan-India-Australia, Australia-UK-US(AUKUS), India-Australia-Indonesia, India-Australia-France, and India-Israel-UAE-US(I2U2)—are creating a network of security cooperation and sharing the regional security burden. Japan’s latest security strategy is based on such an idea. Japan will share the security burden with the US by possessing strike capability and providing arms to countries in this region as one of the security providers of the US-led circle. Could you elaborate on Japan’s South Asia policy, its priorities, and its interest in this region? In the past, Japan did not have a strategy in South Asia. Japan supported many infrastructure projects in South Asia purely because Japan tried to contribute to the local society. However, since China expanded its influence in South Asia and provoked Japan in many places in the Indo-Pacific, Japan’s attitude has changed. Because China’s infrastructure projects are the ones with high-interest rate, it created huge debt and Sri Lanka needed to give China the right to control Hambantota port. This is one typical example of how dangerous China’s hegemonic ambition has become. This time, the National Security Strategy of Japan clearly wrote “Strategic Use of ODA.” Japan will continue many infrastructure projects in South Asia as pure assistance. But at the same time, Japan will increase the projects to save local countries and dissuade China’s hegemonic ambition. How do you see the growing rivalry between the US and China in the Indo-Pacific region? The most recent US National Security Strategy indicated that US-China competition will escalate. The document states: “The PRC is the only competitor with both the intent to reshape the international order and, increasingly, the economic, diplomatic, military, and technological power to do it. And three factors indicate that America is on the road to win the competition with China. First, the US is still stronger than China. A SIPRI database indicates that the US military expenditure in 2020 was three times bigger than China’s. In addition, the US has more allies. The number of political partners has been a decisive factor in geopolitical competition. For example, in WWI, the winning side comprised 32 countries, but the losing side was composed of just four countries. In WWII, the winning side had 54, but the losing side had only eight. In the case of the US-Soviet Cold War, the winning side had 54 countries, but the defeated side had 26. In the case of the current US-China competition, the US has 52 legal-based formal allies including NATO, the Central and South American countries, and Middle East and Asian allies like Japan. But China has only North Korea as a formal ally. The history of the US indicates that the US will win the competition with China. 246 years ago, the US was a single colony of the British Empire. But they transformed into the world’s only superpower now. During this time, all rivals of the US, including Germany, Japan, and the USSR, disappeared. This means that the US system is a successful system to be powerful and win the competition. And indeed, the US had a long-term plan to win the competition. For example, before WWII, the US had an “Orange Plan” to defeat Japan and implemented it. But when that plan was declassified in 1974, the world was surprised to learn that there were also other plans, including a “Red Plan” to defeat Britain and Canada. Both in WWI and WWII, the US supported the British. But because the world is changeable, it is understandable that the US was prepared for any type of contingency. If the US National Security Strategy states that “the PRC is the only competitor,” it is natural to conclude that the US has the plan to defeat China. US Republicans and Democrats share many similar goals toward China. The Trump administration’s so-called ‘high-tech war,’ which banned products from Huawei and ZTE, started when the Investigative Report on the U.S. National Security Issues Posed by Chinese Telecommunications Companies Huawei and ZTE was published in 2012, during the Obama administration. The current Biden administration also continued the policy. The US’s objectives in this competition have bipartisan support. Therefore, considering these situations, we should stand with the US because being on the winning side is beneficial. And three factors indicate that America is on the road to win the competition with China Where does India stand on the US-China rivalry? India and Japan share the same set of problems. For example, in the sea around the Senkaku Islands of Japan, China has employed its coast guards and increased its activities. In 2011, the number of Chinese vessels identified within the contiguous zone in the waters surrounding the Senkaku Islands in Japan was only 12. But the number increased to 428 in 2012, 819 in 2013, 729 in 2014, 707 in 2015, 752 in 2016, 696 in 2017, and 615 in 2018. By 2019, the number had reached 1097. A comparison between the number of Chinese vessels identified within the contiguous zone in the waters surrounding the Senkaku Islands in Japan and China’s incursions in the Sino-Indian border area are similar. In 2011, India recorded 213 incursions in the Sino-Indian border area, but in the following years, the numbers were larger: 426 in 2012, 411 in 2013, 460 in 2014, 428 in 2015, 296 in 2016, 473 in 2017, 404 in 2018, and 663 in 2019. These incursions are similar to China’s activities around the Senkaku Islands of Japan. Based on the number of Chinese incursions in the India-China border area and Chinese activities in the sea around the Senkaku Islands, it becomes apparent that China has increased its assertiveness in 2012 and 2019 in both regions. Therefore, India should cooperate with the US, Australia and Japan. However, cooperation also has a risk. In the QUAD, India could be the first target of China to make pressure. India shares a land border with China and the US, Australia and Japan do not. It is easier for China to provoke India by using ground and air forces. In addition, India is not a treaty-based formal ally with the US like Australia and Japan are. View from China is that India is the weakest link. If China wants to make pressure to disband QUAD, India could be the first target. Therefore, India wanted to be low profile in the QUAD military cooperation despite India promoting military cooperation with other QUAD members. However, China’s recent provocation against India on the India-China border changed India’s attitude. The more China escalates the situation, the more the QUAD should become institutionalized and cohesive. What are your suggestions to the countries like Nepal regarding the conduct of foreign policy in this turbulent geopolitical environment? The above mentioned answer indicated two things. Firstly, China’s infrastructure projects and economic support could be a ‘debt trap’. Japan’s one is workable and far better. Second, America is on the road to winning the competition with China. The winning side is always beneficial. But when Nepal shows a clear stance against China, China will provoke and try to punish Nepal. Therefore, Nepal should gradually distance itself from China. For Nepal to cooperate with the QUAD side more deeply and steadily is the best policy.

Thapa throws down the gauntlet in party’s premiership race

It’s official—Gagan Kumar Thapa has entered the prime minister’s race. The Nepali Congress general secretary will contest the parliamentary party leadership election against the incumbent, Sher Bahadur Deuba, on Wednesday.

Thapa, 46, is widely regarded as one of the most popular leaders both inside and outside his party. Many see him as the future of Nepal’s grand old party.

Inside the NC, winning the PP leader election is a prerequisite for becoming a prime ministerial candidate. Thapa’s candidacy was made possible after senior leader Shekhar Koirala, Deuba’s main rival in the party, decided not to run in the election.

Koirala will be supporting Thapa’s bid for PP leadership. Party leaders say Koirala agreed to pave the way for Thapa on the condition that the latter reciprocate the support when he runs for the party presidency in 2025.

Koirala and Thapa had worked together in the 14th general convention of the party held in 2021 when Koirala lost the leadership race to Deuba and Thapa was elected general secretary.

After the Nov 20 general elections, both Koirala and Thapa were planning to vie in the PP election to unseat Deuba, a record five-time prime minister who is now plotting for a sixth stint.

Youth NC leader Pradeep Poudel and General Secretary Bishwa Prakash Sharma have also supported Thapa’s bid. Meanwhile, senior leader Ram Chandra Poudel has backed Deuba.

A one-time rival of Deuba, it is said Poudel agreed to help the incumbent after he was offered the party’s candidate for the next president of the country.

In terms of numerical strength, Deuba, 76, holds a considerable sway in the party. Party leaders say it won’t be easy for Thapa.

Out of 89 lawmakers elected from the party this past election, nearly 60 belong to the Deuba camp.

The party statute states that a PP leader candidate should muster the support of 50 percent lawmakers. Political analyst Bishnu Dahal says this is a big opportunity for Thapa to emerge as a serious contender for the party leadership, though the chances of him winning the PP election appears slim. He adds that Thapa will have to garner a sizable vote numbers in order to strengthen his position in the NC.

Senior journalist Harihar Birahi, who closely follows Congress politics, has termed Thapa’s PP leadership bid as “bold and courageous”.

He says Thapa has galvanized the party’s rank and file who have long desired for a change.

Birahi adds Koirala’s move to back Thapa is also meaningful in that he has shown that unlike Deuba, he is willing to give young leaders a chance to lead.

Deuba’s political journey

Born in 1946 in a socially and economically backward far-western region, Deuba began his political career as a student leader. He became the chairman of the party’s far-western students’ committee from 1965 to 1968. In 1994, he was elected as PP leader for the first time, which paved the way for him to become prime minister. Deuba went on to cement his position in the party, and in the 10th general convention of the NC held in 2001, he contested for party presidency. In 2002, he broke away from the party due to the differences with the then party president, Girija Prasad Koirala. In the process, around 40 percent of leaders and cadres joined the Deuba-led Nepali Congress (Democratic). The incident showed Deuba’s influence in the party. Deuba returned to NC in 2006, taking 40 percent share in all party organizations. His ambition to become the party president materialized in 2016. After Deuba failed to garner 51 percent votes to win the presidency outright in the 13th general convention, a second round of vote was conducted. And this time, he received 58 percent of the vote with the support of the Krishna Prasad Sitaula faction.

Deuba’s marriage with Arzoo Rana also helped him strengthen his position in national politics as well as in the party. It was Arzoo who helped Deuba connect with the monarchy. In the late 1990s, when the monarchy had a powerful influence in politics, Deuba became prime minister for two terms in 2004-2005, and 2001-2002.

Thapa’s political journey

A former student leader, Thapa has risen through the party ranks in an incredible fashion. Born in Kathmandu in 1976, Thapa was elected as a member of Free Student Union of Trichandra College in 1993 and later went on to become the president of the campus committee. He became the general secretary of the union in 2001. As a student leader, Thapa shot to fame for organizing protests against monarchy. He was elected as the general secretary of NC in 2021 and has previously served as a health minister. He is among the few well-read politicians of Nepal, who holds a master’s degree. He became a Congress lawmaker for the first time as a member of the first Constituent Assembly (CA) in 2008. From then on, he has continued to win elections from Kathmandu-4.

He was appointed the health minister in 2017. Thapa is popular among the party cadres, but when it comes to the Central Working Committee or PP, he has few supporters. The NC leadership structure is largely dominated by old faces, and for a young leader like Thapa to get to the top is difficult.

Deuba’s political journey

Born in 1946 in a socially and economically backward far-western region, Deuba began his political career as a student leader. He became the chairman of the party’s far-western students’ committee from 1965 to 1968. In 1994, he was elected as PP leader for the first time, which paved the way for him to become prime minister. Deuba went on to cement his position in the party, and in the 10th general convention of the NC held in 2001, he contested for party presidency. In 2002, he broke away from the party due to the differences with the then party president, Girija Prasad Koirala. In the process, around 40 percent of leaders and cadres joined the Deuba-led Nepali Congress (Democratic). The incident showed Deuba’s influence in the party. Deuba returned to NC in 2006, taking 40 percent share in all party organizations. His ambition to become the party president materialized in 2016. After Deuba failed to garner 51 percent votes to win the presidency outright in the 13th general convention, a second round of vote was conducted. And this time, he received 58 percent of the vote with the support of the Krishna Prasad Sitaula faction.

Deuba’s marriage with Arzoo Rana also helped him strengthen his position in national politics as well as in the party. It was Arzoo who helped Deuba connect with the monarchy. In the late 1990s, when the monarchy had a powerful influence in politics, Deuba became prime minister for two terms in 2004-2005, and 2001-2002.

Thapa’s political journey

A former student leader, Thapa has risen through the party ranks in an incredible fashion. Born in Kathmandu in 1976, Thapa was elected as a member of Free Student Union of Trichandra College in 1993 and later went on to become the president of the campus committee. He became the general secretary of the union in 2001. As a student leader, Thapa shot to fame for organizing protests against monarchy. He was elected as the general secretary of NC in 2021 and has previously served as a health minister. He is among the few well-read politicians of Nepal, who holds a master’s degree. He became a Congress lawmaker for the first time as a member of the first Constituent Assembly (CA) in 2008. From then on, he has continued to win elections from Kathmandu-4.

He was appointed the health minister in 2017. Thapa is popular among the party cadres, but when it comes to the Central Working Committee or PP, he has few supporters. The NC leadership structure is largely dominated by old faces, and for a young leader like Thapa to get to the top is difficult.

Race for Sheetal Niwas

It’s the curse of coalition politics. Nepal’s major political parties are caught in a whirlwind of negotiation and bargaining to form a new government. At stake are the key positions of prime minister, speaker and president. Talks have begun between the Nepali Congress and CPN (Maoist Center) on sharing prime minister, Speaker and president, while the CPN-UML is also approaching other parties to explore the possibilities of government formation. UML Chairman KP Sharma Oli on Saturday said he was closely following the power-sharing talks inside the incumbent five-party ruling coalition.. Some UML leaders say a split in the current five-party coalition, led by the Congress, will pave the way for UML-Maoist possible partnership for government formation, and they are already in talks with the Maoists. But with all three major parties making a beeline for the next premiership, the attraction of the post has somewhat become a secondary prize. No matter who becomes the next prime minister, it is almost certain he will not get to enjoy the full five-year term. So, the power-sharing negotiations seem to have pivoted towards the posts of president and speaker. The experience of the last five years has clearly shown that even the president and speaker, despite being ceremonial posts, could wield significant influence and power over the executive. The president and speaker can work in the interests of their respective parties, even though it goes against the hallowed tenet of separation of power. The NC leaders are publicly saying the party should not make unnecessary compromises on the presidential candidate. On Saturday, NC General Secretary Bishawa Prakash Sharma said at an event that a full-term presidency was more important to the party than a half-term premiership in a coalition government. The five-party coalition is far from reaching a consensus with its member parties. The coalition leader, NC, wants to retain its position of the executive head as well as install its presidential candidate at Sheetal Niwas. The Maoist Center and other coalition partners, on the other hand, are saying that the Congress cannot have both ways. They are insisting that the NC pick one of the two posts. Other leaders in the ruling coalition have also shown their interest to become the next president. Prior to the Nov 20 elections, Jhala Nath Khanal, a senior leader of CPN (Unified Socialist), had proposed divvying up the posts of president and speaker. Some coalition leaders, including Pushpa Kamal Dahal of the Maoist Center, want Unified Socialist chair Madhav Kumar Nepal to become the next president. But sources say Nepal has been telling leaders that he would rather become a prime minister. From the NC, the potential presidential candidates are Ram Chandra Poudel, Krishna Sitaula and KB Gurung. If UML gets the position of president in its power sharing talks with either the NC or the Maoist, Subas Nembang is its preferred candidate. A former speaker, Nembang was a UML presidential candidate in 2017 as well, but incumbent President Bidya Devi Bhandari, also from the UML, was elected for the second term. Incumbent Vice President Nanda Bahadur Pun and former speaker Agni Prasad Sapkota, are among the presidential aspirants from the Maoist Center. If the Maoist Center gets the position, the party is likely to tap Sapkota for the job. According to a Maoist leader, chairman Dahal has already given his green signal to Sapkota, who did not contest the parliamentary election this time. Other leaders in the party also see Amik Sherchan as the likely candidate for the next president. Sherchan is currently the Province Chief of Lumbini Province.

Opening a Pandora's box

The government’s decision to put forward an ordinance to amend sub-section 116 of the National Criminal Procedures Act, 2017 has drawn widespread criticism. If the ordinance gets the President’s approval, it will allow the government to withdraw political cases pending in any court of law. President Bidya Devi Bhandari is likely to authenticate the ordinance. The ruling political parties maintain that there is a cross-party agreement to withdraw cases of “political nature”. As per existing law, the government can withdraw only those cases pending in district courts. Political experts say the ordinance is meant to secure the incumbent five-party coalition a comfortable majority in parliament to form a new government. Previous governments had signed agreements with various political outfits pledging to withdraw criminal cases against their leaders and cadres. Those cases range from the Maoist insurgency to the deal that KP Sharma Oli-led government signed with the Netra Bikram Chand-led Communist Party of Nepal. Major parties are demonstrating double standards vis-a-vis these cases. If it serves their immediate interests like government formation, they have no qualms in calling these cases “political”. Human rights activists say that withdrawal of such cases amounts to a grave violation of human rights—it will tarnish the country’s image and promote impunity. The ordinance aims to provide blanket amnesty to all kinds of serious crimes committed under any political guise. It impinges on the jursidiction of the judiciary. The ordinance also directly contravenes the stipulations of international conventions and treaties that Nepal is a party to. It will, in all likelihood, complicate Nepal's attempt to garner support of democratic world in concluding its transitional justice process. The National Human Rights Commission, civil society groups and conflict victims have demanded that the government withdraw the controversial ordinance. Constitutional expert Bipin Adhikari says: “Even if some cases are withdrawn by amending the laws, it will unleash a never-ending series of withdrawing criminal cases through political means. It will contribute to the culture of impunity.” Securing the release of Resham Lal Chaudhary, the founding chair of Nagarik Unmukti Party, appears to be the immediate objective of this ordinance. Chaudhary stands convicted of masterminding the 2015 Tikapur incident, in which eight people, including a senior Nepal Police officer and a toddler, lost their lives. At that time, political parties were divided on how to take this massacre — some saw it as a political issue, while others termed it as a criminal one. Chaudhary’s supporters claim that the investigation report of the incident, prepared by Justice Girsh Chandra Lal, does not implicate Chaudhary. Many feel that Chaudhary has been unjustly jailed. Lal’s report has not yet been made public. A large section of the Tharu community seems to feel that Chaudhary has suffered injustice. This grievance has been manifested this past election. Nagarik Unmukti Party, registered under the leadership of Chaudhary’s wife Ranjeeta Shrestha, won three House of Representatives seats under the First-Past-The-Post (FPTP) electoral system. The same party’s Lalbir Chaudhary won as an independent candidate from Bardiya-2. Chaudhary’s party has won 12 seats in provincial assemblies and secured almost 300,000 Proportional Representation votes as well. This shows the sympathy of the Tharu community towards Chaudhary. With 136 seats in the federal parliament, the current ruling coalition is just two seats short of the majority it needs to form a government. Securing Chaudhary’s release at this time could be key to the government formation process. Defending the ordinance, Gyanendra Bahadur Karki, minister for information and communication, says it aims to enhance national unity by bringing all political forces on board. Another senior government minister claims that the ordinance has nothing to do with government formation, saying there is an all-party consensus on the ordinance. The ordinance, the minister adds, is in line with agreements signed between the previous government and different political parties and outfits. CPN-UML has opposed the ordinance, even though it has been brought to implement the agreements signed between the then Oli-led government and different political outfits. Former home minister Ram Bahadur Thapa had signed an agreement with the Chand-led Nepal Communist Party on March 4, 2021. He had also signed an 11-point deal with CK Raut of Independent Madhesh Alliance on March 8, 2018. Similarly, Lilanath Shrestha, law minister in the Oli government, had signed a similar agreement with Rukmini Chaudhary of Tharuhat Joint Struggle Committee on June 1, 2021. Cross-party leaders say the spirit of these agreements is paving the legal way for withdrawal of pending cases against leaders and cadres of these groups that have joined mainstream politics. They say it is similar to the withdrawal of cases against Maoist chair Pushpa Kamal Dahal, senior leader Baburam Bhattarai and other leaders after the signing of Comprehensive Peace Accord (CPA) in 2006. Former prime ministers Dahal, Bhattarai and Madhav Kumar Nepal recently met Chaudhary in Dillibazaar Prison after Nagrik Unmukti Party’s spectacular performance in the elections. What the ruling parties do not seem to realize is that this ordinance, if passed, will open too big a can of worms. They seem least bothered that it will make way for the government to withdraw criminal cases, some of them of serious nature, against leaders and cadres of the political parties including former Maoist combatants. They could walk out in the name of political prisoners, cleared of all charges and convictions. The CK Raut-led Janamat Party has already set the precondition of withdrawal of cases against its leaders and cadres to join the government in the making. Naturally, the ordinance has drawn criticism from all quarters and pressure is mounting on President Bidya Devi Bhandari not to approve it. “It’s an absolutely wrong move. I wonder who gives suggestions like this to the government. This is unacceptable,” says political analyst Puranjan Acharya of the ordinance. “The present government, which is essentially a caretaker one after the elections, has no authority to bring such an ordinance. The new government can introduce laws through the parliament if it really needs to.” Some influential leaders of the Nepali Congress have also stood against the ordinance. They are putting pressure on the party leadership to withdraw it. Leaders like Shekhar Koirala, Gagan Kumar Thapa, Bishwa Prakash Sharma and Pradip Poudel have taken to social media to voice their opposition to the legal instrument. Sharma has said the ordinance was brought without any discussion in the party, while Thapa has called for immediate withdrawal of the ordinance ‘brought for the release of criminals’. The anti-establishment leader in the NC, Koirala has said the decision to release individuals convicted by the court through an ordinance is a mockery of the rule of law, parliamentary system and the spirit of politics and democracy. Poudel, meanwhile, has said the solution to all the problems has to be sought from the new parliament, not through ordinances. Bypassing the legislature is not a new phenomenon. Instead of facing the parliament, governments prefer to make laws through ordinances. This is not the first time a ruling party leader has relied on an ordinance on controversial topics. In August last year, the coalition government led by Sher Bahadur Deuba had brought an ordinance to amend some provisions of the Political Parties Act, 2017. The amendments were aimed at easing the procedure for political parties to split. The CPN-UML and Janata Samajbadi Party broke up on the back of the same ordinance. Prior to that, the former government of UML under KP Sharma Oli had also tried to push forth a similar ordinance. It was aimed at saving his government. Former Supreme Court justice Balaram KC says the government cannot withdraw cases in which the judiciary has already delivered its verdict, as such cases can no longer be considered cases of political nature. “It is a gross misuse of ordinance brought to serve political interests,” says KC. “If the government thinks there has been a miscarriage of justice, it can recommend the President to grant pardon in specific cases, but mass withdrawal of cases is against the rule of law.” Constitutional expert Adhikari says if the government thinks that certain cases should be withdrawn, it should prepare a document and discuss it in parliament, rather than introducing an ordinance. “Certain provisions made for a fixed period of the peace process cannot be extended for an indefinite period because the peace process has already concluded,” says Adhikari. Experts fear that the government move could open a Pandora’s Box of similar cases in the future, where people with political reach could easily get amnesty for their crimes.

Dahal’s power grab ploy

The Election Commission (EC) has announced the final results of the November 20 elections. With this, the race for the new prime minister is expected to gather momentum. Preliminary talks among parties on possible power-sharing modalities have already begun. The top leaders of the current five-party coalition have come up with a public statement pledging to keep their collaboration intact. The core of the power-sharing deal obviously is the post of prime minister. Within the coalition, there are two contenders—Sher Bahadur Deuba and Pushpa Kamal Dahal. In his meetings with the Nepali Congress (NC) leaders, Dahal has been claiming his stake to the post of prime minister. But his bargaining power has certainly reduced, given the poor electoral performance of his party. Dahal’s CPN (Maoist Center) has won just 32 seats out of 275-member House of Representatives (HoR). Before the elections, he had expected to emerge as a decisive power with at least 50 seats that could make or break a government. But the election results show otherwise. Desperate, Dahal is now attempting to consolidate his strength in parliament by trying to convince the CPN (Unified Socialist), Janamat Party, Janata Samajbadi Party, Nagarik Unmukti Party, and other fringe parties. He needs to corral support of other parties so that he could bargain for the premier’s post with the NC. Speaking at a public function on December 12 in Kathmandu, Dahal said his party still holds the key. “I can get the support of 60 lawmakers in the House because parties such as Unified Socialist, Janata Samajbadi and other fringe parties would support our party,” he said. On the face of it, Madhav Kumar Nepal of the Unified Socialist, Upendra Yadav’s Janata Samajbadi and leaders of some other fringe parties are likely to back Dahal’s premiership bid. Reports are that Dahal has agreed to fulfill the demands of these parties. There are even talks about possible merger of some of these parties with the Maoists. But even with the backing from the fringe parties, Dahal would still need the nod from either the NC or the CPN-UML to lead the next government. NC leader Deuba has maintained silence regarding Dahal’s prime ministerial ambition so far. While Dahal expects Deuba to hand over the leadership reins of the next government as per their gentleman’s agreement reached before the elections, the latter wants to become the prime minister for the sixth time. The NC leaders are of the view that the party should hand over the government leadership to Dahal after 2.5 years. NC Central Working Committee member Nain Singh Mahar says there could be an agreement with the Maoists on leading the government on a rotational basis. Meanwhile, Deuba also faces pressure within his own party to step down and make way for the new generation leaders. The external influence, mainly of India and the US, also equally matters in the government formation process. Indian Ambassador to Nepal Naveen Srivastava has already intensified talks with major political parties on the government formation process. During his visit to India in July this year, Dahal had reportedly told Indian leaders and officials that the five-party coalition would remain intact. China has not spoken anything about the government formation process, though it is clear that it prefers Dahal to lead the new government. If the current coalition fails to strike a deal on power sharing, there is a high chance Dahal may try to convince the UML. Although Dahal and UML leader KP Sharma Oli do not see eye to eye since the bitter break-up of the erstwhile Communist Party of Nepal (CPN), the leaders of the two parties are currently in talks about forming a left alliance. On December 14, Maoist General Secretary Dev Gurung called on Oli at the latter's Balkot residence to discuss a power-sharing deal between the two parties. Similarly, UML politburo leader Mahesh Basnet, Oli’s confidant, had met Dahal last week. A UML leader tells ApEx that second-rung leaders of the UML and the Maoist are trying to establish rapprochement between Oli and Dahal. “The two leaders are ready to forget their enmity and work together,” says the leader. “We are trying to set up a meeting between them.” But due to Maoist Center’s reduced size in parliament, the UML may not agree to offer premiership to Dahal. The party could, however, agree on a rotational power sharing, just like the one proposed by the NC.

Kishore Bahadur Singh obituary: Fine specimen of an accomplished sportsman

Kishore Bahadur Singh, who served as a member-secretary of the Nepal Sports Council (NSC) from 2002 to 2006, has died. He was 73. According to family members, his cause of death was sudden cardiac arrest. Singh was one of the few people who came from a sporting background and reached the leadership position at the NSC. His life can be broadly divided into two parts—first as a professional athlete and second as an effective bureaucrat. Singh was appointed the 14th member-secretary of the national sports governing body after the restoration of democracy in 1990. Prior to that there was a practice of assigning the job based on his political affiliation. When Singh took on the job, he was someone who actually came from a sporting background, and a decorated one at that. Between 1972 and 1977, he was the reigning national badminton champion. He also represented Nepal at the 1970 Asian Games held in Thailand. Singh was part of the golden age of Nepali badminton. Singh was also exceptionally good outside the badminton court. As a member-secretary of NSC, he made a reputation for being an effective leader. Sports journalist Himesh Ratna Bajracharya says as a member secretary of the sports council, Singh maintained a clean image. He ran his office in a transparent manner and took a series of measures to control corruption. Singh had made it a mission of his to make Nepali sporting field a corruption-free area. He also took many important steps to help the resource-strapped sporting sector of Nepal during his time at the sports council. “I am a player after all. I know how to handle pressure and challenge,” Singh used to tell his colleagues. While he was serving as the member-secretary of NSC, Singh was also associated with Nepal Olympic Committee. But unlike his career in the sports council, his time at the committee was not so smooth. At one point his public image took a hit as a result of a bitter confrontation between the NSC and the committee. The conflict led to the uncertainty about Nepal’s participation in the 2004 South Asian Games held in Pakistan, says Bajracharya. Singh courted criticism from the sporting fraternity when he refused to accept the election results for the leadership of the committee. He would go on to feud with Rukma Shumsher Rana, former member-secretary of the NSC and the honorary president of the Olympic Committee, for a long time.