Photo Feature | An authentic Khukuri isn’t easily (or cheaply) made

Khukuri, every Nepali household probably has one. History is something that is constantly rewritten, and Nepal’s history is no different. Yet, to this day, khukuri remains an enduring symbol of the brave Gorkhas, of Nepali valor in battlefields. It adorns many of our national emblems and insignias of security forces.

This week I visited Khukuri House Handicraft Industry Nepal (KHHI) at Patan Industrial Estate to learn more about the art of making the iconic knife. It has been forging and selling khukuris since 1991.

The process starts with priming of the metal. Gopal Limbu, general manager of KHHI, says only two metal types can be used to make authentic Nepali khukuris: 52100 (a carbon alloy steel) and 5160 (high carbon chromium spring steel).

These metals are either imported from India or collected from scrap yards. “Suspension spring plates are ideal for making khukuris,” says Limbu.

The metals are hammered and forged, which entails beating them under heat to give them the distinct khukuri shape. The blades are then quenched, whereby they are heated in a furnace, dipped in water and beaten repeatedly.

Quenching essentially improves metal’s performance. “It ensures the blade’s strength and quality,” says Limbu. Once the blades are ready they are sharpened and polished.

The blade’s sharpness is tested on buffalo horn, wood and paper. Each strike and slice should make a clean cut, without denting the blade.

Khukuris stand out for its distinct recurve shape, but they are of many kinds, as different as the regions of their origin in Nepal.

The differences, says Limbu, are discernible to khukuri enthusiasts, collectors and makers.

KHHI forges up to 200 khukuris of different kinds and sizes in a week. “Most of our khukuris are exported to the US and Europe,” says Limbu. “We also do commission work.”

The most expensive khukuri the factory ever made went for Rs 200,000.

Photo Feature | Saturday morning leg-flexing at Shivapuri

Okay, with all the rain around, I accept that it’s not the perfect time for hiking. But what the heck, I thought? I could still do it.

So I headed towards Shivapuri National Park with a friend this past Saturday. It was a clear sunny morning (fingers crossed!), in what was near perfect conditions to go hiking in the hills surrounding Kathmandu Valley.

We set out for Bishnudwar, the origin of Bishnumati River and a popular hiking destination.

The hike begins in earnest from the main entrance of Shivapuri National Park at Budhanilkantha, and it can take up to four hours to get to the top. If you have a two-wheeler you can ride all the way up to the village of Dandagaun, from where you can reach Bishnudwar in about two-and-a-half hours.

Rain or shine, there are likely to be many hikers and cyclists along the trail, particularly on weekends, so you are unlikely to get lost.

The way to Danda Gaun from Budhanilkantha is particularly beautiful with its well-preserved path that passes through a forest.

There were many vehicles parked at Dandagaun. They had come bearing hikers and picnickers visiting Bishnudwar on this clear Saturday morning.

If you are coming here for a hike, don’t bother to carry snacks: there are many eateries and resorts at Dandagaun. That way, you will feel lighter on your foot too.

The trail to Bishnudwar from Dandagaun passes through more dense forest, and the path is decent enough for cycles and motorcycles.

Weather permitting, you can also catch stunning views of Kathmandu Valley from some spots.

The main draw of Bishnudwar are its forest stream and the waterfall. The place is generally crowded with selfie-takers and TikTokers during weekends.

You can climb further up towards the main waterfall, but the path can be slippery, so caution is advised.

Photo Feature | When Kathmandu heats up… you go ice-skating

‘Unpredictable’ would be the word to describe Kathmandu’s weather in the month of July. One moment the sun is smiling down on you and the next, the skies are pelting down, sending you scrambling for cover. It’s no fun being outside. So where would you go for fun? Well, Fun Land, for one.

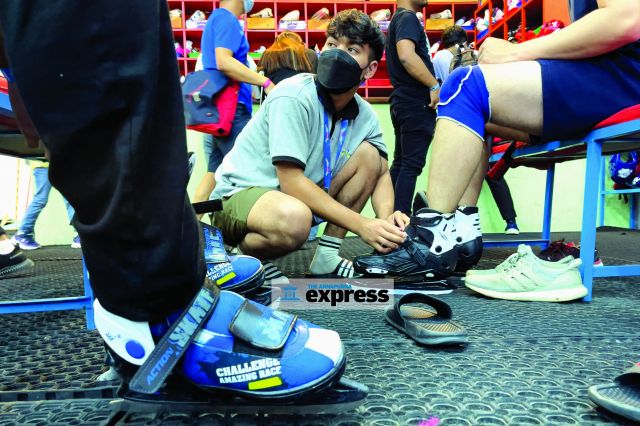

Situated on the Maitighar-Bhadrakali cut-through road, Nepal’s first ice-skating rink is housed in what looks like a large storage building. There, children and adults alike can enjoy a great day without having to worry about the turbulent weather outside.

I visited a recent afternoon, a weekday, expecting few people. But to my surprise the place was a hive of activities. Gaggles of children and teenagers screaming and laughing inside the rink. Most were using skating guides in the shape of dolphins for stability. Those brave enough were guideless—flailing about and falling, yet still getting up for a repeat.

The facility, which opened in April, has around 20 coolers to keep the ice rink cool and firm. The place also offers other fun activities like trampolines, rock-climbing and mechanical bull-riding, but ice-skating is easily the biggest draw.

I was tempted to give it a try but after seeing many people slip and fall, I decided to sit at the nearby food court and watch instead. “How hard could it really be?” I was asking myself after seeing even the adults using funny-looking dolphin guides that also doubled as sleds.

Bhim Bahadur Adhikari, the ice skating captain of Fun Land, satiated my curiosity: “You’ll need to practice sincerely for two to three days if you do not want the support dolphin.”

Fun Land also offers an ice-skating training package. In fact, the instructors, I found out, were trained right there.

Encouraged by Adhikari, I decided to give it a try. A staff member helped me wear the skating boots and I was ready… or so I thought. To my embarrassment, I discovered it was much more difficult than I had thought. I couldn’t maintain balance even with the support dolphin. I had to be held by the instructor just to find my balance, to learn how to stand correctly, before I could use the inanimate plastic dolphin.

Even though I was skating on an ice surface, there was a lot of sweating and panting. I sympathized with the people I was photographing earlier.

Photo feature | The bronze sculpture-maker of Patan

The Patan area of Lalitpur is known for its rich cultural heritage, which has been passed down generations. No wonder so many artisans reside here, plying the trade of their ancestors. Shailendra Maharjan is one of them. He specializes in the art of bronze sculptures of deities, something he learned from his father.

This week I visited Maharjan’s workshop at Patan’s Bholdhoka to find out more about the art.

There are several artisans at the workshop, each with a specific skill required to produce exquisite sculptures, but it is Maharjan who designs the masterpiece and sculpts the visage of the deity being made. He has worked in this field for over two decades in order to perfect this art.

For any sculpture, Maharjan explains, “you need the masterpiece”, a mold made with the mixture of clay and Benzoin resin by heating them together. Heat is mandatory to bring the mixture in shape. Without it, the mixture hardens in no time.

Once the masterpiece is prepared, it is now time to replicate that shape with the melted copper. To create a hollow space to pour the molten copper into, the masterpiece is covered with a mixture of mud and chaff and left to dry in the sun for a couple of days. When completely dry, it becomes rock-solid. It is then taken to the coal burner, where the clay-Benzoin resin mixture melts from the inside. The melted mixture is then removed, leaving just the outer layer with a hole inside.

Once the poured molten bronze has completely cooled down, the mold is broken using a hammer, revealing the sculpture. Sometimes the sculptures turn out to have some holes and patches, which are mended with the use of a hammer and welding. For large statues, Maharjan says, parts of the sculpture have to be made one at a time and attached later.

After that, it is all about final touch-ups. First, the sculptures are given some intricate carvings. They are then plated with a mixture of gold and mercury, giving them a silver color. The next process includes the heating of plated sculpture in fire, during which the mercury evaporates, leaving the sculpture golden. The gold used for the face of the sculpture is 24-carat, while the body uses gold of comparatively lower quality.

Now the only thing left to do is make the sculpture shiny. This process is called buffing.

Lastly, the face of the statue is painted with normal colors, after which the sculptures are ready for delivery.

“Some sculptures can be as large as 12ft and could cost anywhere between Rs 6m and Rs 10m.”

Photo Feature | The hidden powers of healing bowls

The ubiquitous singing bowls we see in curio shops at popular tourist destinations in Kathmandu valley are more than souvenirs. So says Hasina Shakya, who specializes in singing bowl therapy. “They are sacred and possess amazing healing powers,” she says.

Shakya is a therapist at Amoga Handicrafts and Healing Bowl Center, located inside the premises of the Golden Temple in Patan, Lalitpur. On this day she was administering therapy on her own husband, who cannot walk properly.

Shakya swears by the healing powers of the singing bowls. “He could not even leave his wheelchair before. But after two years of regular therapy he can walk a short distance with external support,” she says.

Singing bowls—or healing bowls, in therapy parlance—come in all shapes and sizes, and each has a specific purpose. The sounds and vibrations they emanate are said to promote not just mental and bodily relaxation but also to clear energy blockages that supposedly result in illnesses. This healing approach is generally associated with Buddhism, but Shakya says people of all faiths come for therapy.

Patients are usually made to lie supine or sit cross-legged for the therapy, which is sometimes accompanied by a guided meditation session. The bowls are used to produce ringing sound of various tones and lengths, either by a gentle strike of a wooden mallet or by the mallet’s swirling round the bowl’s rim.

Rajesh Shahi, who runs a small souvenir shop at Kathmandu’s Basantapur, says he has been selling singing bowls and working as a therapist for the past 40 years. Like Shakya, he too is a staunch believer of the healing bowl therapy. “It works wonders, particularly if you are stressed or feeling agitated,” he says.

Shanta Shakya, who practices Reiki, a Japanese form of energy healing, at Thamel’s Dynamic Healing Center, says the therapy is about “sharing positive energy with the clients”. “The therapist can share her own or someone else’s energy to heal her clients,” she adds.

Singing bowls indeed produce a calm, relaxing sound, no one can argue against that. But as for their healing powers, all reported benefits are anecdotal. Why don’t you give it a try one of these days and find out for yourself?

Photo Feature | A rainy-day pilgrimage to Swayambhu

It was raining heavily on the morning of June 29, Wednesday. I had to be at Swayambhunath, the famed fifth-century stupa. The plan was to capture the view of Kathmandu valley from up there but the monsoon downpour was relentless. As I was already up, I decided to take my chances. I grabbed my camera bag and took off on my bike.

Fortunately, the rainfall stopped as I reached the iconic Buddhist pilgrimage site. I was hoping to find the place relatively crowd-free as it had been pouring down all morning. But to my surprise, there were many visitors.

Huffing and puffing, I reached the top, with my camera pointed at the wonders of Swayambhu. Undoubtedly, my first impulse was to capture Kathmandu, with Dharahara soaring higher than any other building.

As I moved towards the temple, a group of monks chanting Buddhist hymns caught my attention. They were repeating the six-syllable Sanskrit mantra—‘Om Mani Padme Hum’—which was both peaceful and spiritual. Moving around, I came across several Buddhist devotees lighting butter lamps near the statue of Lord Buddha, one of the attractions of Swayambhu.

The devotees and casual visitors were scattered all around the place: some of them circumambulating the dome-shaped shrine and spinning the prayer wheels, others counting their sacred beads.

I was fortunate that the rain stopped and I got to capture the picture I had planned to, but I got so much more. Apparently, morning life at Swayambhu cannot be hindered–come rain or shine.

Photo Feature | The intricate world of thangka art

Thangka painting is a niche field of art that requires years of training and oodles of patience. The painting itself is exquisite, vivid and full of intricate details, often depicting the life of Buddha and aspects of Buddhism. Considered sacred by the Buddhist faithful, they are more than art-pieces. This week, I visited a thangka gallery at Kathmandu’s Boudha to see what goes into making these artworks. The gallery owner was kind enough to oblige me.

He works with a small cohort of master artists, who make thangkas of all shapes and sizes for him. The gallery walls are adorned by the works of these masters. One of the thangkas by artist Man Bahadur Lama was priced at Rs 10m.

“The price of a painting is determined based on the details, the time it takes to complete the piece, and the artist behind it,” says the gallery owner. The process of painting itself is a demanding task. Master artists are required to go through many ancient books and follow several specific steps to create the intricate thangka patterns.

The gallery also runs a store where thangkas paintings are sold. Here, the cheapest painting is priced at Rs 25,000. The person managing the store says most customers are foreigners, the majority of them Chinese Buddhists.

“Thangkas are generally expensive also because they require special canvas and highly durable colors,” the store manager says.

To make his point, he guides me to a corner of the store where hundreds of thangkas are kept, each one rolled up like a parchment.

I learned that a well-made surface (canvas) is all it takes for a thangka to last for centuries. The canvas is woven out of cotton thread on a wooden frame. Once the canvas is ready, a special concoction (jesso) is applied on the surface to retain the colors applied by the artist. The colors used in the thangka paintings are specially brought from the Himalayas, as they are believed to be indelible. Twenty-four karat gold dust is also used in thangka painting.

“The fact that thangkas can be rolled up make them convenient for transport and storage. The painting won’t be damaged unless you expose it to the elements for long or treat it roughly,” says the store manager.

Photo Feature | One rainbow, many colors

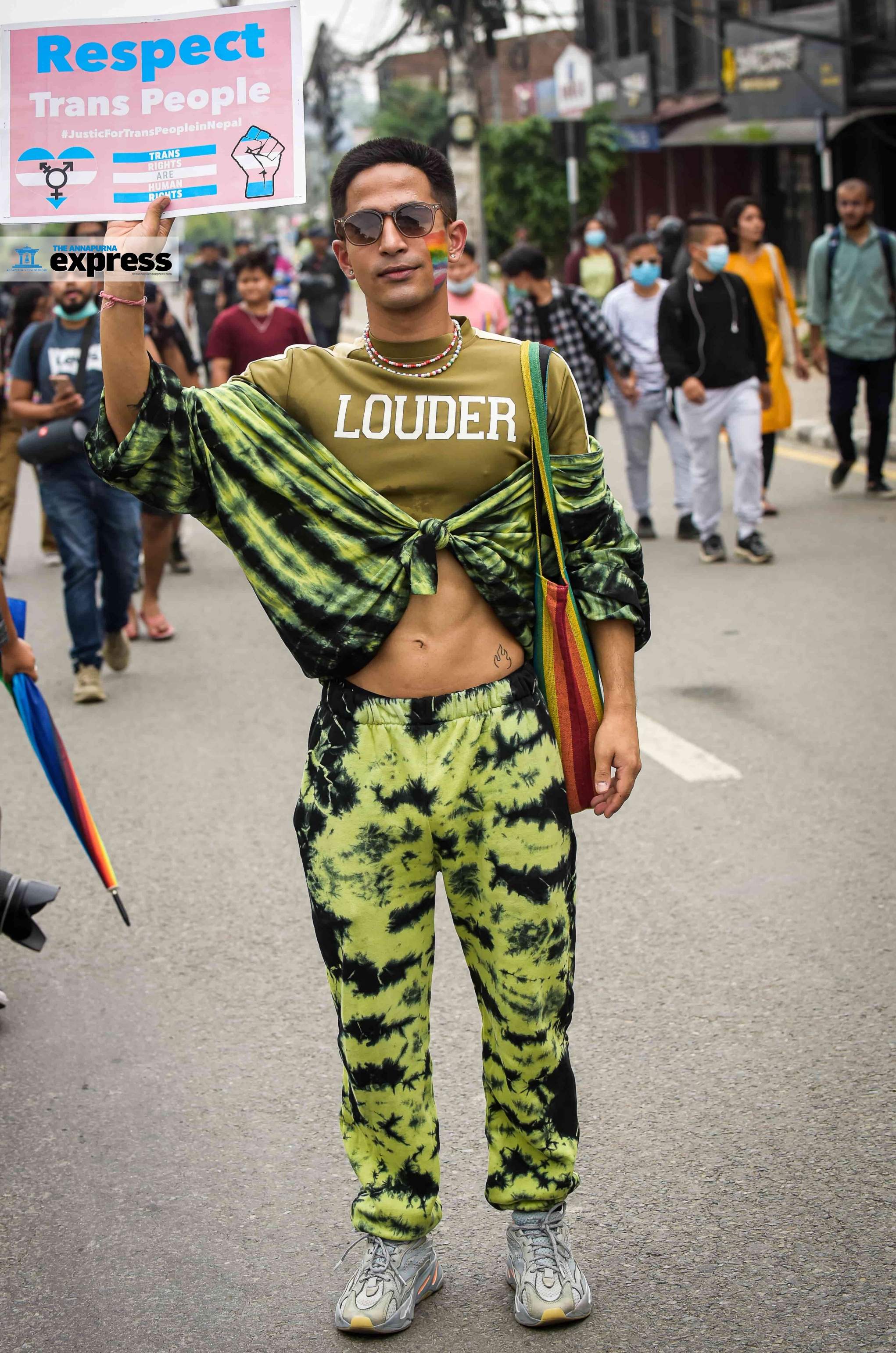

Under a 10-meter-long ‘Rainbow Pride Flag’ stood every single person who had come out or were still explorating their sexual orientation and identity. It was all about being proud of who you are and what you identify as. Blaring from the speakers was Lady Gaga’s ‘Born this way’—a perfect soundtrack for the occasion.

Rukshana Kapali, she/her, pansexual, transwoman

Rukshana Kapali, she/her, pansexual, transwoman

The mass was gathered at Kathmandu’s Maitighar on Saturday (June 11) to celebrate the Pride Parade, a celebration of queer people and their community. As the crowd moved towards New Baneshwor, I and photographer Pratik Rayamajhi followed this colorful procession, talking to many of the parade participants.

We talked to the individuals representing the many colors in the queer spectrum: gay, lesbian, non-binary, bisexual, pansexual, gender fluid, among many others.

Participants painting their faces before the parade

Participants painting their faces before the parade

Some had come wrapped-up with the flag representing their sexuality, some had their face painted with the color to announce their identity, while many sported rainbow-coloured socks.

Not everyone in the crowd belonged to the queer community though. Numerous participants were cis-gender people who had come to show their solidarity with the queer community.

SJ, she/her, non-binary

SJ, she/her, non-binary

The parade’s key takeaway was love and acceptance. There was no groupism, no discrimination. Everyone at the parade was a member of one big family. And like any family, each member had their own unique characteristic and was loved for it. There was acceptance, appreciation, and happiness, which after all is what the Pride Parade is all about.

Saddu (left), he/she/they, unlabeled and Apsara, she/her, pansexual

Saddu (left), he/she/they, unlabeled and Apsara, she/her, pansexual

We met many individuals, talked to them, and captured their proud and jubilant mood. ‘Happy Pride! Happy Pride!’ we chanted to exchange greetings to mark the day. The parade came to a halt at New Baneshwor and everyone sat down. It was time for celebrating the queer identity and for expressing love for one and all present. There were dance performances and recitals of prose and poetry. There were tears of sadness and tears of joy. There were moments of melancholy and moments of mirth.

Peachy Pie, she/her, drag queen

Peachy Pie, she/her, drag queen

Parakram Rana, he/him, gay

Parakram Rana, he/him, gay