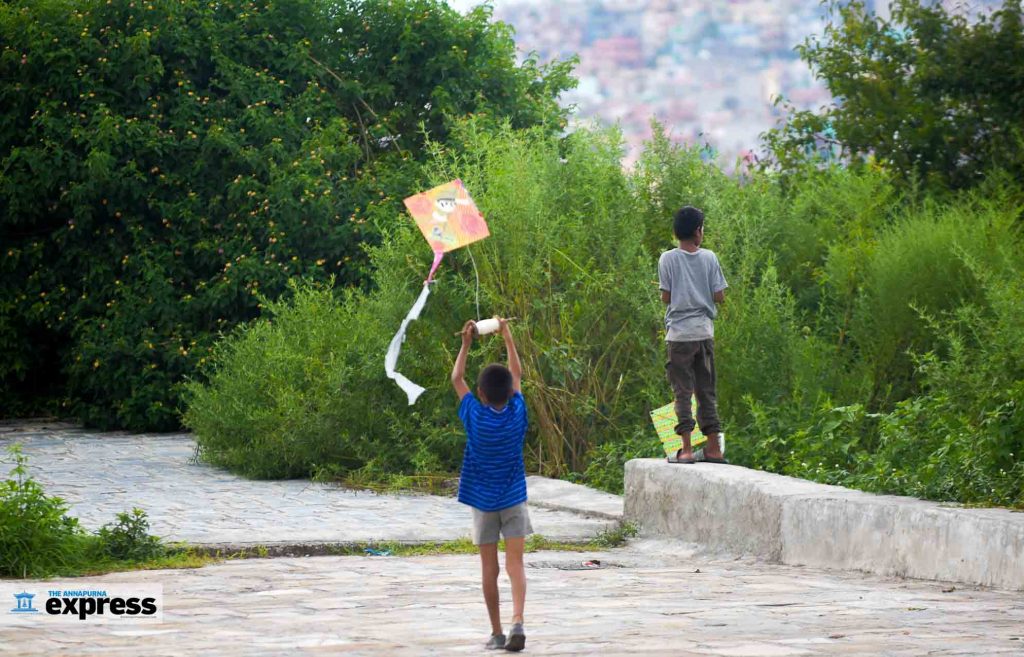

Photo Feature | Dashain is in the air

Dashain is here. You can feel it. Mornings are pleasantly warm and everything suddenly looks sharply focused. More tellingly, shopping areas are crowded, there are more vehicles on the roads and kites in the sky.  Bus ticket counters are packed with people trying to get hold of tickets so that they could travel home in time for the big festival, while in the outskirts of Kathmandu Valley, traditional swings are being erected.

Bus ticket counters are packed with people trying to get hold of tickets so that they could travel home in time for the big festival, while in the outskirts of Kathmandu Valley, traditional swings are being erected.  This week, I turned my lens to all things that represent the greatest festival of Nepali Hindus.

This week, I turned my lens to all things that represent the greatest festival of Nepali Hindus.  The 10-day festival kicked off with Ghatasthapana (Sept 26). The day is observed by planting of barley seeds, whose sprouts are used as a blessing of goddess Durga on the day of Bijaya Dashami.

The 10-day festival kicked off with Ghatasthapana (Sept 26). The day is observed by planting of barley seeds, whose sprouts are used as a blessing of goddess Durga on the day of Bijaya Dashami.  Dashain is a festival celebrating the victory of good over evil. According to the Hindu mythology, goddess Durga had slayed demon Mahishasura in a battle that lasted for 10 days. The first nine days symbolizes the battle which took place between the different manifestations of Durga and Mahishasura. The tenth day is the demon was killed.

Dashain is a festival celebrating the victory of good over evil. According to the Hindu mythology, goddess Durga had slayed demon Mahishasura in a battle that lasted for 10 days. The first nine days symbolizes the battle which took place between the different manifestations of Durga and Mahishasura. The tenth day is the demon was killed.  But for most Nepalis, Dashain is more than just its religious symbolism. It is also about family reunion. People living in city areas for job or study head to their hometowns to be with their loved ones.

But for most Nepalis, Dashain is more than just its religious symbolism. It is also about family reunion. People living in city areas for job or study head to their hometowns to be with their loved ones.

Photo Feature | A taste of honey

Sarita Bhattarai Shrestha got into bee farming 10 years ago. Over the years, she has become a successful entrepreneur. This week, I visited her farm to find out what it takes to become a bee farmer.

Mountain Bee Concern Pvt Ltd is based in Dhapakhel, Lalitpur. The place serves as an apiary, honey processing and packaging factory, and a training center. Besides overseeing the farm and factory works, Shrestha also conducts beekeeping training here.

Mountain Bee Concern Pvt Ltd is based in Dhapakhel, Lalitpur. The place serves as an apiary, honey processing and packaging factory, and a training center. Besides overseeing the farm and factory works, Shrestha also conducts beekeeping training here.

A training session was underway on the day I reached the place. A small group of people wearing net hats were standing among rows of brood boxes, while a trainer explained to them how to spot the queen bee.

A training session was underway on the day I reached the place. A small group of people wearing net hats were standing among rows of brood boxes, while a trainer explained to them how to spot the queen bee.

Shrestha has a small team of trainers who run theory and practical classes three times a day. The training program aims to encourage youth entrepreneurship, says Shrestha. “Nepali youths are spending hundreds of thousands of rupees to go abroad when they can earn so much here,” she says.

Shrestha has a small team of trainers who run theory and practical classes three times a day. The training program aims to encourage youth entrepreneurship, says Shrestha. “Nepali youths are spending hundreds of thousands of rupees to go abroad when they can earn so much here,” she says.

Mountain Bee Concern currently has over 1,800 brood boxes where honey bees are reared for honey. These boxes are moved to Chitwan during dry season when there aren’t many flowers around for bees to feed on.

Mountain Bee Concern currently has over 1,800 brood boxes where honey bees are reared for honey. These boxes are moved to Chitwan during dry season when there aren’t many flowers around for bees to feed on.

Shrestha’s annual turnover just from honey sales is over Rs 10m and she employs around 40 people. “All it takes is small investment and the willingness to put in some effort to become a successful bee farmer,” says Shrestha. “I tell this to all my trainees.”

Shrestha’s annual turnover just from honey sales is over Rs 10m and she employs around 40 people. “All it takes is small investment and the willingness to put in some effort to become a successful bee farmer,” says Shrestha. “I tell this to all my trainees.”

Photo Feature | Dengue stalks Kathmandu Valley

Cases of dengue infection have reached an alarming level in Kathmandu and other parts of the country. The first case in Kathmandu was reported in May, and the caseload has crossed well over 1,000 in little over four months. Countrywide, the infection numbers have surpassed 8,000 and there have been at least a dozen fatalities.

Epidemiologists and public health experts say the relevant government health agencies should take immediate steps to contain the infection before the situation takes a turn for the worse.

Epidemiologists and public health experts say the relevant government health agencies should take immediate steps to contain the infection before the situation takes a turn for the worse.

Hospitals and health facilities across the country have been reporting a rise in daily dengue cases. At Kathmandu’s Sukraraj Tropical and Infectious Disease Hospital, most hospital visits and admittance are concerning dengue these days.

Hospitals and health facilities across the country have been reporting a rise in daily dengue cases. At Kathmandu’s Sukraraj Tropical and Infectious Disease Hospital, most hospital visits and admittance are concerning dengue these days.

Dr Manisha Rawal, the hospital director, says nearly 2,800 people have tested positive for dengue since mid-July and 240 people needed to be admitted. “We are receiving 150 to 200 patients daily,” says Rawal. “Ten or so cases are serious and the patients need hospital stay.”

Dr Manisha Rawal, the hospital director, says nearly 2,800 people have tested positive for dengue since mid-July and 240 people needed to be admitted. “We are receiving 150 to 200 patients daily,” says Rawal. “Ten or so cases are serious and the patients need hospital stay.”

She says since dengue has no cure or standard treatment, it should be considered a dangerous disease. She says dengue patients present a wide range of symptoms from mild to severe. The only thing hospitals and health facilities can do for severely ill patients is administer them medicines to relieve their symptoms.

She says since dengue has no cure or standard treatment, it should be considered a dangerous disease. She says dengue patients present a wide range of symptoms from mild to severe. The only thing hospitals and health facilities can do for severely ill patients is administer them medicines to relieve their symptoms.

The first case of dengue in Nepal was reported in 2004. The infection has been reported regularly since. In 2010, over 900 dengue cases and five deaths were reported, in what was Nepal’s first dengue epidemic. Dengue was classified as an epidemic in 2016, 2017, 2018 and 2019 as well, with the disease stalking more than 60 districts.

The first case of dengue in Nepal was reported in 2004. The infection has been reported regularly since. In 2010, over 900 dengue cases and five deaths were reported, in what was Nepal’s first dengue epidemic. Dengue was classified as an epidemic in 2016, 2017, 2018 and 2019 as well, with the disease stalking more than 60 districts.

A disease historically endemic to the region with hot climate, dengue is now being reported in hill areas, including Kathmandu. Dr Baburam Marasini, former director at Epidemiology and Disease Control Division, told ApEx in a recent interview that climate change had contributed to the spread of the mosquito-borne diseases like malaria and dengue in the hill and mountain regions of Nepal.

A disease historically endemic to the region with hot climate, dengue is now being reported in hill areas, including Kathmandu. Dr Baburam Marasini, former director at Epidemiology and Disease Control Division, told ApEx in a recent interview that climate change had contributed to the spread of the mosquito-borne diseases like malaria and dengue in the hill and mountain regions of Nepal.

Dr Rawal suggests as dengue cases are rising, the members of public should take necessary precaution, like wearing full-sleeves, using mosquito nets and repellents at home and covering the areas containing stagnant water, where dengue-carrying mosquitoes (Aedes aegypti) are known to breed.

Dr Rawal suggests as dengue cases are rising, the members of public should take necessary precaution, like wearing full-sleeves, using mosquito nets and repellents at home and covering the areas containing stagnant water, where dengue-carrying mosquitoes (Aedes aegypti) are known to breed.

Photo Feature | Gearing up for Indra Jatra

Indra Jatra, the biggest religious street festival in Kathmandu, kicks off on Friday, Sept 9. The week-long celebrations have two events: Indra Jatra and Kumari Jatra.  The festival starts with the erecting of Linga, a pole from which the banner of Indra is unfurled, at the Kathmandu Durbar Square. It’s then followed by days of elaborate chariot procession of three deities—Ganesh, Bhairav and Kumari, masked dance of deities and demons, and feasts in Newar households.

The festival starts with the erecting of Linga, a pole from which the banner of Indra is unfurled, at the Kathmandu Durbar Square. It’s then followed by days of elaborate chariot procession of three deities—Ganesh, Bhairav and Kumari, masked dance of deities and demons, and feasts in Newar households.  Days ahead of the festival on Wednesday, volunteers and Nepal Army (NA) personnel were busy preparing for the big day.

Days ahead of the festival on Wednesday, volunteers and Nepal Army (NA) personnel were busy preparing for the big day.  Statues, idols, and temples around the square were being spruced up. The temple of Swet Bhairav, which is closed throughout the year, was opened.

Statues, idols, and temples around the square were being spruced up. The temple of Swet Bhairav, which is closed throughout the year, was opened.  The NA personnel, meanwhile, were pulling the tree trunk, which was to be made into the Linga. The tree is brought from the forest near Nala, a small town 29 km east of Kathmandu.

The NA personnel, meanwhile, were pulling the tree trunk, which was to be made into the Linga. The tree is brought from the forest near Nala, a small town 29 km east of Kathmandu.  Not far away from the palace square, a group of masked dancers were performing their ritual dance, while the members of Guruji Paltan of the Nepal Army were practicing the gun salute.

Not far away from the palace square, a group of masked dancers were performing their ritual dance, while the members of Guruji Paltan of the Nepal Army were practicing the gun salute.  Indra Jatra was started by King Gunakamadeva to commemorate the founding of Kathmandu city in the 10th century. Kumari Jatra began in the mid-18th century. The celebrations are held according to the lunar calendar, so this is a moveable feast.

Indra Jatra was started by King Gunakamadeva to commemorate the founding of Kathmandu city in the 10th century. Kumari Jatra began in the mid-18th century. The celebrations are held according to the lunar calendar, so this is a moveable feast.

Photo Feature | Sublime storytelling

A small group of female dancers are busy warming up and getting ready for their class as I enter the Aesthetics Dance Studio housed in the ground floor of a building in Anamnagar, Kathmandu.

They are all dressed in lime-green kurta salwar; the only thing setting one apart from the other are their shawls, tied sideways from their shoulders.

The studio is immaculate: neat parqueted floor, white walls and white curtains, and a large floor-to-ceiling mirror.

They are all dressed in lime-green kurta salwar; the only thing setting one apart from the other are their shawls, tied sideways from their shoulders.

The studio is immaculate: neat parqueted floor, white walls and white curtains, and a large floor-to-ceiling mirror.

The young women are here to learn the classical Indian dance form of Kathak.

Their teacher, Namrata KC, is a graceful woman dressed in a red-and-white sari with a floral pattern and a red blouse.

She is a Kathak veteran who studied the dance-form in Uttar Pradesh, India. She’s been running the studio for the past six years.

The young women are here to learn the classical Indian dance form of Kathak.

Their teacher, Namrata KC, is a graceful woman dressed in a red-and-white sari with a floral pattern and a red blouse.

She is a Kathak veteran who studied the dance-form in Uttar Pradesh, India. She’s been running the studio for the past six years.

“Kathak is one of the eight classical dance forms believed to have originated in Uttar Pradesh,” KC tells me. “The word ‘Kathak’ comes from the Sanskrit word ‘Katha’ or story. So this is a storytelling dance-form.”

Most dance numbers are based on the stories of Hindu gods and goddesses.

“Dancers emote the stories through various hand movements called ‘mudras’, complex footwork as well as facial expressions.”

“Kathak is one of the eight classical dance forms believed to have originated in Uttar Pradesh,” KC tells me. “The word ‘Kathak’ comes from the Sanskrit word ‘Katha’ or story. So this is a storytelling dance-form.”

Most dance numbers are based on the stories of Hindu gods and goddesses.

“Dancers emote the stories through various hand movements called ‘mudras’, complex footwork as well as facial expressions.”

Dancers also tie ghungroos (musical anklets) to their feet to set the sound and rhythm of their dance movements, which are equally meaningful in storytelling.

Aesthetics Dance Studio is among the few dance conservatories in Nepal that teach Kathak. KC is glad that many young people are showing interest in the dance.

Dancers also tie ghungroos (musical anklets) to their feet to set the sound and rhythm of their dance movements, which are equally meaningful in storytelling.

Aesthetics Dance Studio is among the few dance conservatories in Nepal that teach Kathak. KC is glad that many young people are showing interest in the dance.

Most of her students are in the 22-35 age group. Every now and then, KC and her students also participate in cultural shows and festivals to showcase their skills.

“My students come from various professional backgrounds,” says KC. “They are here to learn Kathak out of passion, which is what you need the most to master this dance-form.”

Most of her students are in the 22-35 age group. Every now and then, KC and her students also participate in cultural shows and festivals to showcase their skills.

“My students come from various professional backgrounds,” says KC. “They are here to learn Kathak out of passion, which is what you need the most to master this dance-form.”

Photo Feature: Off to the mystic Mohini Waterfall

The village of Markhu in Makwanpur is a popular destination for many folks in Kathmandu looking for a weekend getaway. The village overlooking the Kulekhani reservoir is nearly halfway between Kathmandu and Hetauda.

One can easily find hotels and resorts here and there are plenty of things to do for visitors. Boating in the reservoir and hiking to Bheda Farm, a scenic pastureland, are two of the most popular activities. But many of them miss out Markhu’s hidden gem: Mohini Waterfall.

One can easily find hotels and resorts here and there are plenty of things to do for visitors. Boating in the reservoir and hiking to Bheda Farm, a scenic pastureland, are two of the most popular activities. But many of them miss out Markhu’s hidden gem: Mohini Waterfall.

This week, I visited the famed waterfall with a friend of mine. It was a journey fraught with misadventures—bad weather, lost ways and jungle-walk after dark. But then we came across the majestic waterfall, which made our trip more than worthwhile.

This week, I visited the famed waterfall with a friend of mine. It was a journey fraught with misadventures—bad weather, lost ways and jungle-walk after dark. But then we came across the majestic waterfall, which made our trip more than worthwhile.

We set out from Kathmandu on a scooter fairly late at around 12:30 pm, as it had been raining since early morning on the day of our journey. We reached Markhu at around 3pm via the Chandragiri route. (One can also take the alternative route from Pharping.)

We set out from Kathmandu on a scooter fairly late at around 12:30 pm, as it had been raining since early morning on the day of our journey. We reached Markhu at around 3pm via the Chandragiri route. (One can also take the alternative route from Pharping.)

Weather was not the only thing that turned on us that afternoon. Our old two-wheeler betrayed us in several segments of the Kathmandu-Markhu ride. It could not pull our weight on inclines.

Weather was not the only thing that turned on us that afternoon. Our old two-wheeler betrayed us in several segments of the Kathmandu-Markhu ride. It could not pull our weight on inclines.

In ideal conditions, Mohini Waterfall is about two-hour hike from Markhu. There is also the option for a 45-minute short hiking route. For this, one must take a motorboat across the reservoir and ascend a steep stone stairway.

In ideal conditions, Mohini Waterfall is about two-hour hike from Markhu. There is also the option for a 45-minute short hiking route. For this, one must take a motorboat across the reservoir and ascend a steep stone stairway.

This was the route I and my friend took.

There is also a route for motorcycles, all the way up to the waterfall. One must cross the headwaters of the reservoir, usually impassable during the monsoon, to catch this route. But the two hiking trails are accessible around the year.

This was the route I and my friend took.

There is also a route for motorcycles, all the way up to the waterfall. One must cross the headwaters of the reservoir, usually impassable during the monsoon, to catch this route. But the two hiking trails are accessible around the year.

We reached Mohini Waterfall late in the afternoon. The place was fairly packed despite not-so-promising weather. Visitors were soaking in the view, taking photos, swimming in the plunge pool and pitching tents for an overnight stay.

We reached Mohini Waterfall late in the afternoon. The place was fairly packed despite not-so-promising weather. Visitors were soaking in the view, taking photos, swimming in the plunge pool and pitching tents for an overnight stay.

On our return trip, it began to rain heavily and we decided to take shelter at a nearby tea shop. It was already dark and the rain would not stop. We also missed the boat ride back to Markhu because it was already gloomy. So we took a long hiking trail through the forest with light from our mobile phone showing us the way. Soaking wet, we reached Markhu at 9:30 pm and rode our scooter back to Kathmandu.

On our return trip, it began to rain heavily and we decided to take shelter at a nearby tea shop. It was already dark and the rain would not stop. We also missed the boat ride back to Markhu because it was already gloomy. So we took a long hiking trail through the forest with light from our mobile phone showing us the way. Soaking wet, we reached Markhu at 9:30 pm and rode our scooter back to Kathmandu.

Photo Feature | Remembering the dead, celebrating their lives

The Newar community of Kathmandu valley observed Gai Jatra on Aug 12. It is a festival held every year in the Nepali month of Bhadra to honor (and in memory of) the loved ones who passed away in the past year.

On this day, families of the deceased send cows or family members dressed as cows to take part in a procession around town. The procession is accompanied by Newari traditional music, and locals offer milk, fruits, curd, beaten rice and money to the participants. By doing so, it is believed, the dead will find a passage to heaven.

On this day, families of the deceased send cows or family members dressed as cows to take part in a procession around town. The procession is accompanied by Newari traditional music, and locals offer milk, fruits, curd, beaten rice and money to the participants. By doing so, it is believed, the dead will find a passage to heaven.

This week, I visited Basantapur Durbar Square and Bhaktapur Durbar Square to capture the ‘festival of the dead’. Gai Jatra celebrations in the two cities are starkly different.

This week, I visited Basantapur Durbar Square and Bhaktapur Durbar Square to capture the ‘festival of the dead’. Gai Jatra celebrations in the two cities are starkly different.

In Kathmandu, where the festival is said to have been started by King Pratap Malla to console his queen following their son’s death, the participants of the procession largely comprised of children, many of them dressed up, their faces painted and donning a headgear symbolizing a Gai (cow), a sacred animal for Hindus. Some of the participants were dressed as Lord Krishna, who grew up as a cow herder in the Hindu mythology, while others were carrying the pictures of their loved ones.

In Kathmandu, where the festival is said to have been started by King Pratap Malla to console his queen following their son’s death, the participants of the procession largely comprised of children, many of them dressed up, their faces painted and donning a headgear symbolizing a Gai (cow), a sacred animal for Hindus. Some of the participants were dressed as Lord Krishna, who grew up as a cow herder in the Hindu mythology, while others were carrying the pictures of their loved ones.

In Bhaktapur, though, there were no children dressed as cows. Here, the festival participants were dragging bamboo chariots (Taha-macha) around the town with the pictures of their loved ones. The chariot procession ended after encircling the Bhairav temple. But the celebrations continued with music, dance and costume parades.

In Bhaktapur, though, there were no children dressed as cows. Here, the festival participants were dragging bamboo chariots (Taha-macha) around the town with the pictures of their loved ones. The chariot procession ended after encircling the Bhairav temple. But the celebrations continued with music, dance and costume parades.

All the pomp and ceremony for the departed ones, not to mourn their death but to celebrate the rich life they lived.

All the pomp and ceremony for the departed ones, not to mourn their death but to celebrate the rich life they lived.

Photo Feature | Self-managing waste is no rocket science

Garbage bags are stacking up in our homes, neighborhoods and streets, and Kathmandu’s waste collectors have gone AWOL. Rapper-turned-mayor Balen Shah is not getting any kudos from his voters, that’s for sure. After all, solving the city’s perennial solid waste problem was one of his top election agendas. Whatever happened to segregating household waste?

But wait, we can’t wash our hands of this mess just yet.

Apparently, there is one solid way to manage solid waste. It’s called vermi-composting or worm-composting, a fairly simple and inexpensive way of turning biodegradable waste into organic manure that you can use on your vegetable patch or garden.

Kanchha Maharjan has been doing just this. At his Swayambhu house, he has set up a small vermi-composting space that provides all the nutrients for his rooftop vegetable garden and house plants and flowers.

Maharjan, who started this pursuit to keep himself busy post-retirement, has become something of an expert in vermi-composting. “You don’t need any expertise for this,” he says. “All it takes is a small space to grow earthworms [vermiculture].”

He explains that vermicomposting is natural decomposition of organic wastes but in a controlled environment. And all it requires is soil, cow-dung, earthworms, water and organic waste. Most of the work is done by the worms—and mother nature.

Thanks to Maharjan’s pursuit, his family does not have the problem of garbage bags piling up at their home. In fact, he has turned vermicomposting into a business. He sells the organic fertilizer for Rs 50 a kg and the earthworms and their eggs for Rs 3,000 per kg.

Some way to turn waste into money! Besides vermicomposting, he also practices rainwater harvesting to water the vegetables, plants and flowers. He has set up a large copper tank to collect rainwater that he filters using bleaching powder and other traditional methods. Maharjan and his family have a sustainable household—something we should all aspire to.