What if… Kathmandu valley had a metro service?

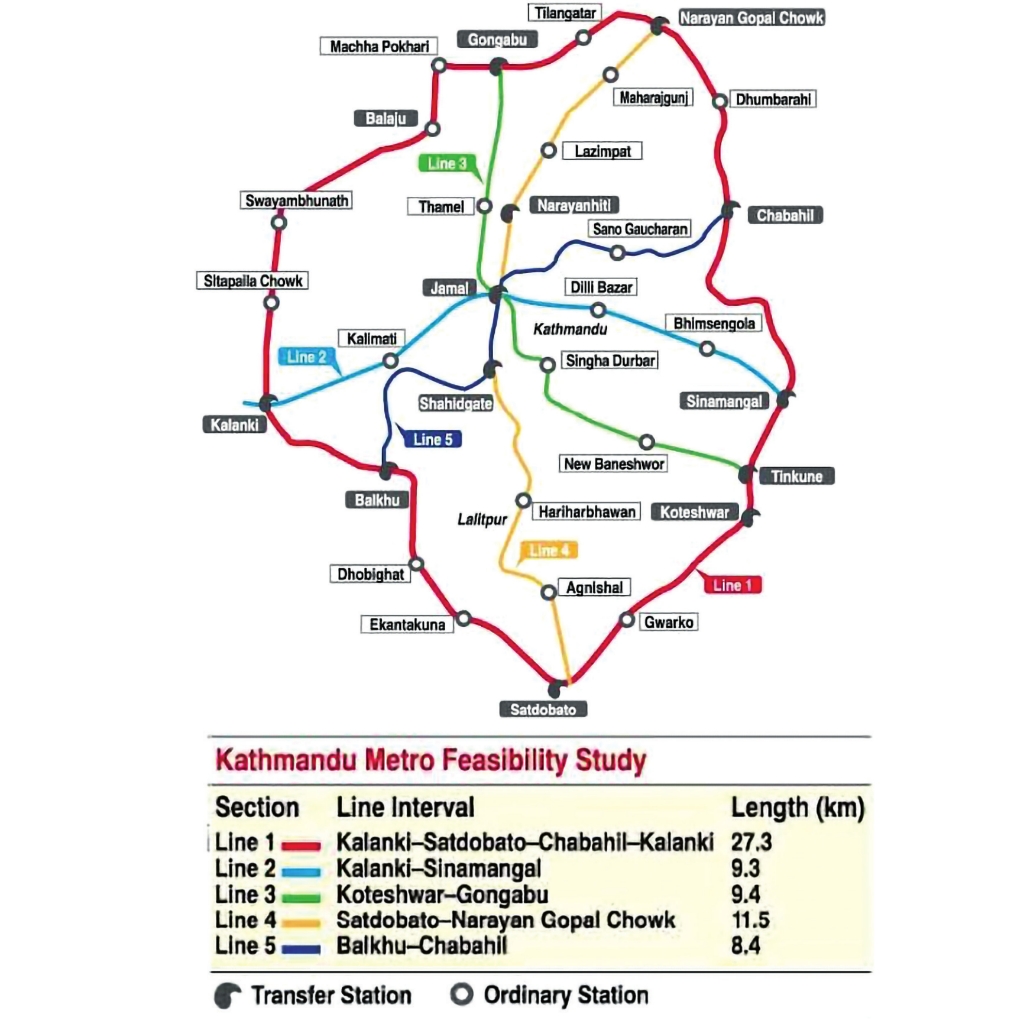

Back in 2011, the government had been looking into the possibility of a metro system in Kathmandu valley and carried out a feasibility study at five different places in core areas. Covering a distance of over 75km and including underground and elevated rail, the planned five lines, one of which was to run along the ring road, would connect most of the valley’s major nodes.

The government was even looking for possible donors and outside support. Fast-forward a decade and the development project is on the backburner. But experts insist increasing congestion in valley roads can be managed only by a mass transport system. Else, it will soon be impossible to commute in Kathmandu.

“If Kathmandu had a metro system, it would mean fewer vehicles on the roads and better connectivity. In places with high population density, the only way to increase mobility is through mass transport options,” says Padma Bahadur Shahi, president, Society of Transport Engineers Nepal. Shahi stresses the need for a Mass Rapid Transit, a mode of urban transport to carry large volumes of passengers quickly, for a thriving economy. He says more movement is vital for economic prosperity, for which fast travel is an imperative.

Kathmandu’s roads are choc-a-bloc with vehicles, garbage and construction materials. Road-expansion hasn’t done much to ease congestion. Without proper public transport, the number of private vehicles plying the roads keeps increasing each year. Nepal Motor Vehicles Sales recorded 21,805 sold units in 2019, way up from 1,400 in 2005. According to a report by the Metropolitan Traffic Police Division, if all vehicles in Kathmandu valley were to be lined up, at 7.2 million feet, it would be longer than the total length of the valley roads (4.5 million feet).

Poor public transport

Aman Chitrakar, senior divisional engineer and spokesperson at the Department of Railways under the Ministry of Physical Infrastructure and Transport, says Kathmandu valley urgently needs a railway system. The government had commissioned the detailed project report (DPR) for it but work has been on halt for some time. Chitrakar says Nepal is still dilly-dallying on the metro when it’s already too late. “Kathmandu’s floating population needs a metro service to ease congestion and provide people with an efficient mode of transport but we are still stuck in studies and preliminary activities,” he says.

Experts say every city needs good public transport—and it’s the government’s duty to ensure that. Nepal has failed to provide this essential service. It’s natural for major cities to face congestion but public transport should largely solve that. But there aren’t fitting government-run services to meet Kathmandu’s growing commuting needs.

The private buses aren’t reliable, as they don’t have fixed schedules and routes. Business-oriented as they are, their poor services (mainly unruly behaviors of drivers and conductors) and overcrowding have compelled many to save up and buy their own bikes or cars.

“With a metro service in the valley, people wouldn’t feel the need to buy vehicles. Kathmandu valley wouldn’t be so chaotic and polluted,” says Shahi, citing the examples of New York and Boston (in the US) and London, Manchester and Birmingham (in the UK) as cities with excellent public transport links. It’s not unusual for people there to ditch personal cars. Chitrakar says there is no alternative to a metro as nothing else can provide the same mass transport service: a standard metro can carry over 30,000 people an hour in a direction.

The many challenges

But there are many constraints to developing a railway service in the valley. The Lalitpur Metropolitan City office apparently opposed the railway plan as the city sees a lot of jatras and authorities weren’t in favor of rail lines running above holy chariots. In areas where underground metro construction isn’t possible, overhead lines will narrow roads. Similarly, heritage sites in Kathmandu valley might obstruct railway paths. Another major challenge will be the valley’s uneven terrains. And then there is also the matter of railways ruining city aesthetics.

Not that having a metro in Kathmandu is an impossible dream. But there must be enough studies and research before committing to such an ambitious and important project. Roshan Devkota, civil engineer, feels Nepal needs to understand its transport requirements and work out a practical and sustainable solution. So far, it hasn’t been able to run effective bus services. Metro, Devkota says, will pose an even bigger challenge.

It’s also not just about building a metro system. The operation phase too should be planned in advance. “Having a metro is not enough, you should also be able to run it effectively. The government should work on making the metro service-oriented rather than not profit-driven,” he says.

Spokesperson Chitrakar emphasizes the need for more investment in public transport. There is no other way out. Madan Bandhu Regmi, urban transport development expert, says the current state of public transport in Kathmandu valley is appalling. First, it is primarily run by private companies, and that shouldn’t be the case. Second, it’s not enough or cheap. Many low-income families still have to think twice before using the bus on a daily basis. According to Regmi, public transport should run on government subsidies and people shouldn’t have to pay much.

Exploring options

“Metro can help improve transport in Kathmandu valley. But it’s not the only option,” says Regmi, explaining that what is really needed is an integrated transport system. When they work in collaboration, various forms of public transport, like buses, tempos, and railways can brilliantly interlink people and places in Kathmandu valley where different areas have different infrastructures and requirements.

The focus should be on developing and using these modes of transport interchangeably. “The metro doesn’t need to connect all places in the valley. Where the metro can’t go, buses and tempos can fill the gaps. We need data and information to determine what is needed where. Then we need to work on developing a system accordingly,” he says.

Shahi says the government doesn’t have a framework of development. Its priority is ever-changing, prone to whims and fancies of those in power. Lack of foresight and unwillingness to conduct in-depth studies have always been the government’s weaknesses and the public ends up paying the price. There have been many studies on the valley’s public transport needs but the government has yet to endorse a single one, says Regmi. He says the way forward is to review all the studies till date to figure out how to create an interconnected multi-modal transport system.

That done, it can break the project down into sizable bits and get donor agencies and development partners involved. “The government takes so much development tax from us, year after year, but it isn’t able to spend. So, it actually has the financial means to build a metro in Nepal. It won’t even need outside help if it’s serious about it,” says Regmi.

Also, confusingly, there are different departments and ministries looking after urban transport in the valley. The Department of Railways, the Department of Roads, the Kathmandu Valley Development Authority and various metropolitan city offices are a few of the government bodies that deal with transport development. This, Regmi says, creates chaos and confusion and delays work.

Without coordination between these agencies, often there is no clarity on who is responsible for what. “We need a separate government department to deal with the various aspects of urban transport. It should be given all the authority required to create a system that works,” he says.

Second-hand shopping: More than just a bargain

Sukhawati Store in Samakhusi, Kathmandu, which sells second-hand stuff at nominal prices, has recycled 40,000 kg of clothes since its 2014 launch. These clothes would have otherwise ended up in the Sisdol landfill that is already inundated with the valley’s trash. There are quite a few other second-hand stores in the valley and many more online accounts, especially on Facebook and Instagram, selling all kinds of pre-owned items, from clothes and accessories to gadgets and furniture. Thrifting—once a social taboo of sorts—is now considered a sustainable, eco-friendly option for shopping.

Samita Rana, program officer at Sukhawati, says when they started their main objective was to make good clothes accessible to low-income families. People who didn’t fall in that category hesitated to enter the store as the items there were all second-hand. But there has been a shift in that mindset in the past couple of years. Now their customers aren’t only those who can’t afford to shell out thousands of rupees for a dress or a sweater. Many youngsters also shop second-hand because they know it has a low impact on the environment and it has become trendy, too. Rana says the new generation, those between the ages of 20 to 35, seem to be especially keen on thrifting.

“People have a lot of stuff that they are looking to get rid of in an eco-friendly way. Social media has made it easier to sell those things by just posting a few pictures online,” says Rana. Hiroshi Khanal, who is soon launching the Instagram store Thrift Capital Nepal, testifies to that. He says he and his sister want to sell things they don’t need anymore. The money from it, Khanal says, will be donated to an orphanage they support. “Thrifting is a great way to make cash from your trash. We have finished collecting things we want to sell. Now, we will do a quick photoshoot and start uploading them,” he adds.

Rana believes buying things second hand is the only way to reduce consumption and eventually decrease production, putting a cap on fast fashion’s devastating carbon footprint: the fashion industry contributes an estimated 10 percent of the world’s greenhouse-gas emissions. According to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, by 2030, emissions from textile manufacturing are projected to go up by 60 percent. Fast fashion is also labor- and resource-intensive. It takes 10,000 liters of water to produce a kilogram of cotton or approximately 3,000 liters of water for a single cotton shirt. There have also been numerous reports of forced and child labor in the fashion industry in Bangladesh, China, India, Philippines, Vietnam, and Brazil, among others—countries that make the clothes available in our market today.

In 2013, an eight-floor commercial building in Dhaka, Bangladesh named Rana Plaza collapsed, killing 1,134 workers and injuring more than 2,500. The building housed garment factories of American and European brands. A 2015 documentary, ‘The True Cost’, shows the events leading up to the incident. Apparently, right before the collapse of the Rana Plaza, the laborers had been forced into the factory despite a crack being seen in the walls. The documentary reveals more horrors of exploitation in what is a labor-dependent industry. According to director Andrew Morgan, employees are subjected to humiliation and live on low salaries besides working in toxic environments in unsafe buildings.

Buying previously-owned stuff keeps products in circulation for longer and that can eventually curb excess production and wastage. Manish Jung Thapa, founder of Antidote, says you extend an item’s life when you buy second-hand and with more and more people doing it, it can have a huge environmental and social impact. These days, in Nepal, it definitely isn’t just those without the financial means who are opting for second-hand items. Women who work in the development sector, well aware of the implications of their actions, seem to be more inclined to thrift. Then there are also those who want to save money. “When you can get something for Rs 500, nobody wants to spend four or five times that amount,” says Thapa, explaining the current allure of thrifting.

However, there needs to be strict quality control to ensure second-hand doesn’t literally mean rubbish. Else, people will quickly lose faith and hesitate to shop at thrift stores. Aavas Rajkarnikar, who deals in second-hand vintage electronics, says customers often ask many questions before making a purchase. This, he says, is because products don’t come with warranties. It’s not uncommon for thrift stores to have a no-return or exchange policy as well. Thapa of Antidote says they have a 100 percent money back guarantee if an item they sell isn’t as specified on their page. “This kind of approach to thrifting can make it risk-free and help popularize it even more,” he says.

Sunaina Shrestha, founder of Thriftmandu, says many thrift stores in Nepal sell quality stuff, including branded items and people really shouldn’t hesitate to make second-hand purchases. She thinks the problem is that many of these stores are limited to online platforms, and having physical outlets would make things easier. That way, she says, people can check an item before buying it and be assured of its good condition. Thapa, on the other hand, feels the media should talk more about thrifting and familiarize more people with the idea and its importance. Social media influencers and celebrities could also play a pivotal role in promoting this sustainable behavior, he says.

Thrifting has long been a popular culture in western countries with the likes of Oxfam, Goodwill, and Salvation Army running charity shops where people can buy a variety of things at affordable prices. In Nepal, books and furniture have always had good second-hand markets. Narayan Sapkota has been selling used books at Bhrikuti Mandap, Kathmandu, for over 30 years. There are more like him in the area. Used-furniture stores are a dime a dozen in the valley.

Yet people are still skeptical about pre-owned clothes and other personal items like shoes and accessories. But reusing clothes can contribute to a circular economy like no other: the fashion industry, according to The World Economic Forum, produces 150 billion garments a year globally, nearly three fifths of which end up in the landfill within a few years. “People are slowly starting to realize that reusing and recycling clothes is kinder on the planet and starting to donate or sell their clothes instead of tossing them in the trash. But there are still far too many who don’t care,” says Rana.

Disappearing act: Where are Kathmandu’s trees?

In the 14th century, Nepali King Jayasthithi Malla levied a fine of five rupees (a hefty sum at the time) on those who cut trees along the roadside. Additionally, they would be sent to prison. The king is believed to have instructed his officials to encourage people to plant trees. In the 1900s, Rana prime ministers like Chandra Shamsher and Juddha Shamsher had hundreds of trees planted along Kathmandu valley roadsides. After the 1934 earthquake, Juddha Shamsher included tree plantation in the restoration process. But as the urban population grew, trees were cut down to make space for buildings, road expansion, and for obstructing traffic. It didn’t help that modern urban planning that started around 1960-70 was haphazard and preserving plantation was the last thing on the authorities’ minds.

But trees are important to make a city livable. Not only do trees make any space aesthetically pleasing, they also help regulate urban heat and are great filters for pollutants. According to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization, one tree can absorb as much as 150 kg of carbon dioxide annually. It adds that when it comes to cooling urban areas, strategically planting trees can cool air by between two to eight degrees Celsius. Say the experts ApEx spoke to, one solution to air pollution could be increasing the number of trees and green spaces in urban areas.

Niranjan Shrestha, environmentalist, Environmental Services Nepal Pvt. Ltd., says a city shouldn’t just have concrete buildings and wide roads. It also needs elements of nature like birds and trees. But that isn’t the case in Kathmandu where the focus is only on road expansion and building construction. Big trees in the middle of roads and footpaths are being felled to facilitate movement. There are plantation drives being carried out but, Shrestha says, they are not thought through and thus have little to no impact on environment preservation.

Sanat Adhikari, chairperson of Youth Alliance for Environment, says lack of foresight is turning Kathmandu valley into a concrete jungle. The Nepal government, Adhikari laments, only focuses on concrete buildings and road expansions in its development projects. Worse, other cities are emulating Kathmandu’s plans and policies and slowly becoming as crowded and chaotic. The government has time and again tried to come up with plantation projects to offset the damage. In 2013, the Kathmandu Metropolitan City hatched the two-tree policy whereby every new house in Kathmandu would have to plant two trees if it wanted the blueprints to be passed by the authorities. But that wasn’t possible as many houses were built in tiny plots. Campaigns to plant trees either didn’t see the light of day or the saplings weren’t cared for after plantation.

The situation might be bleak but it’s still salvageable if the local authorities step up, says Adhikari. From creating special plantation zones so that every community has at least a few green patches, to buying small plots of land to build gardens and parks, the work must begin at the local level. It’s also imperative to factor in plantation in areas still undergoing expansion. In places like Pulchowk and Naya Baneshwor, there are various plants on road dividers. While these plants that are grown in small spaces might aid the area’s beautification, they don’t contribute much towards a thriving ecosystem.

“We need studies and planned policies to bring back greenery in Kathmandu valley. If urban development continues as it is, ours will soon be the most unlivable city in the world,” warns Shrestha. Development that comes at the cost of the environment isn’t sustainable and we will, sooner or later, have to pay the price. Apart from reducing carbon emission, trees can absorb water and decrease the risk of urban flooding. In the past few years, many places in Kathmandu valley had knee-high water as rainfall ran into the rivers during monsoon. Few trees and more concrete roads and buildings can potentially lead to drying up of groundwater as well. Its effects can already be seen: Kathmandu valley’s water-table has been steadily dwindling.

Activists have always protested the felling of trees for road expansion but the authorities’ stance is that development necessitates it and that there is no other way out. However, says Narayan Bhandari of Kathmandu Valley Development Authority, we must find ways to incorporate greenery in urban planning to balance runaway urbanization. The current plan, of leaving at least five percent open space while building a structure, hasn’t been enough to promote the kind of environment friendliness the valley requires. Bivuti Basnet, president, We for Change, a youth-led organization, says people, driven by economic gains, aren’t very environmentally conscious. The long-term effects of ignoring nature, and not living in harmony with it, can be devastating, she says, so what Nepal needs right now is an eco-sensitive development approach where the focus isn’t on cutting down trees but planting more.

But planting trees requires more than the commitment to do so. Experts say it’s important to study what can be planted where, with the soil quality, temperature and requirements of the space in mind. For instance, poplars and eucalyptus shouldn’t be planted near concrete structures such as pavements and buildings as their roots grow close to the soil-surface, cracking and damaging foundations. Bhandari of KVDA agrees that many trees were cut as they were unsuitable for the place they were planted. Either they were damaging the surrounding structures or their drooping branches were posing various dangers to those moving about.

“We need studies to determine which plants will thrive in which place in Kathmandu. Once that is determined, it falls on the local authorities to do the rest,” says Shrestha. However, that needs a team of experts—gardeners, botanists, environmentalists etc.— and the local authorities are strapped for manpower. That problem could be tackled by collaborating with concerned ministries, like the Ministry of Physical Infrastructure and Transport and the Ministry of Forest and Environment. And lastly, once planted, they need care and maintenance and someone has to be accountable for that.

Love in an unaccepting world

How is a man loving a man or a woman loving a woman different to a man loving a woman? It’s still the same butterflies in the tummy, the same need for companionship, and the same desire to have a family of one’s own. But our black and white notion of what’s ‘natural’ and the homophobia that mindset leads to have made it difficult for the LGBTIQA+ community to live like the rest of us. There is no social and legal recognition of queer relationships and that makes love a tough terrain to navigate.

“The LGBTIQA+ community is treated differently and that leads to many problems. Not allowing us to marry who we want leads to emotional trauma,” says Pinky Gurung, president of the Blue Diamond Society. Moreover, this violation of their basic human rights robs them of a dignified life. Gurung says she has seen many cases of fraud and even abuse because there are no laws governing gay, lesbian or transgender relationships. A year ago, Sunita Lama, LGBTIQA+ rights activist, was cheated out of her life savings. Her partner of 14 years emptied Lama’s bank accounts and took off. Lama filed a complaint but the authorities said there was nothing they could do as her partner had no legal obligation towards her.

“This kind of thing can happen to anyone but it happens all too often in the LGBTIQA+ community as without legal recognition of relationships, it’s easy to take in new or multiple partners. There’s no sanctity of relationships,” says Lama. What her partner did has left Lama bereft and unable to trust anyone. She has had a few romantic interests but each time she has taken a step back, told herself not to give into her emotions. She feels she’s setting herself up for hurt and disappointment by being romantically involved. “Unless our rights are secured and marriage in our community is protected by law, we will continue to suffer,” she says.

To love and be loved is a basic human need. It’s all the more important for people of the LGBTIQA+ community in Nepal as many of them are shunned by their own families. Their parents, siblings, relatives, and friends want nothing to do with them and so they crave acceptance. This reality, Gurung says, makes them vulnerable to exploitation. Someone only has to show them a little love and they are willing to do anything that person says to make sure s/he sticks around. But due to lack of societal acceptance and legal binding, these relationships soon fizzle out. Even those in serious relationships are sometimes unable to deal with family pressures and leave their partners.

“Many LGBTIQA+ youths have been forced to marry people their parents choose for them,” says Gurung. This ruins two lives. Often, it leads to domestic violence and even marital rape. Gurung says such members of the community suffer from depression and other mental conditions. There have been several cases of attempted suicide. “Our society doesn’t care about our happiness as it doesn’t value us. But we have the right to live life on our own terms. They shouldn’t get to decide what is right or wrong for us,” she says.

The constitution grants equal rights to marginalized communities and states that LGBTIQA+ people fall in that category. Their rights are guaranteed in Articles 12, 18, and 42 but the constitution doesn’t explicitly mention same-sex marriage. Marriage equality (a political status in which same-sex marriage and opposite-sex marriage are recognized as equal by the law), however, is an essential part of the constitution’s anti-discrimination provision. Yet biases run deep in the system and despite many attempts to legalize same-sex marriage, there has not been much progress.

The state’s reluctance to make laws for marriage equality and implement them creates uncertainty. That, in turn, breeds fear, not allowing the LGBTIQA+ community to live and love freely. Rubina Tamang, a trans-woman who has been in a relationship for four years, says she and her partner hesitate to plan for the future as they know they have no rights as a couple.

Tamang’s parents, time and again, try to ‘talk sense into her’. They want her to leave her partner and return home. Many things hinge on whether or not they will be able to marry and be granted the same rights as other married couples. Legalization of same-sex marriage or marriage within the queer community would address other issues like access to IVF for lesbian couples and the possibility of adoption. “It would give us some sense of stability and safety. We would be able to be a family,” says Tamang.

Neelam Poudel, make-up artist, model, and transgender rights activist, says relationships can be fickle for members of the LGBTIQA+ community and it’s best to be cautious when deciding its course. Poudel has been in tumultuous relationships in the past. The joys of acceptance, she says, were always limited to the confines of their private space. As a trans-woman, none of the men she has dated have had the courage to openly accept their relationship. “A man might claim to love you but he won’t hold your hand in public,” she says. “It’s disheartening and humiliating.”

But before blaming the government for failing its citizens, Poudel says the community should evaluate itself as well. She says there is a somewhat warped notion of love among the LGBTIQA+ people. Most of them are quick to fall in love because they are desperate for some semblance of normalcy. Many give expensive gifts to their partners with the hope that it will make them stay. Poudel says there are many people who want to ‘try out new things’ and experiment and for that get into relationships with transgenders. They quickly get bored and move on, oblivious to the fact that they have emotionally scarred another person.

“LGBTIQA+ relationships are fragile and people of the community are often mistreated as there are no rules to protect our rights,” says Bhumika Shrestha, vice-president of the Federation of Sexual and Gender Minorities, Nepal. Policy makers are concerned about LGBTIQA+ marriages contributing to a sharp decrease in population and ending lineages. There’s also the fact that society still doesn’t accept them despite quite a few years of pretending to do so. That, Shrestha says, is why their issues are always sidelined—nobody really cares. “We are humans and must be treated like everyone else. Only societal acceptance will allow us to live and love freely,” she says.

Reading in the time of corona

There was a time when coffee table books and guidebooks made the major chunk of annual book sales. Bookstores catered to tourists and the occasional local, making the book business a seasonal one. Even until the pandemic, the vast majority of Nepalis were only reading popular bestsellers (think Paulo Coelho and Chetan Bhagat) and those mandated by their curriculum or career. Reading for pleasure or self-improvement wasn’t the norm but the Covid-19 lockdowns changed that, say those in the book business. Now, Nepalis are reading more than ever and their reading tastes are varied. Book businesses have had to up their game to cater to the demand.

“We have more books coming in than ever before,” says Rishab Sharma of Pilgrims Book House. “Our selection is based on what’s popular internationally as well as publishers’ recommendations.” Fiction, he adds, seems to be an all-time favorite while self-help and business-related books are right up there. Manish Sharma Ghimire, founder of Book Corner Nepal, agrees with Sharma and says there are more people reading self-help these days because it helps them make sense of these turbulent times. “People are also recommending books to their friends as tools to cope. We have many people looking for certain books that they heard about from their friends. ‘Atomic Habits’ by James Clear is one book that became popular by word of mouth,” says Ghimire.

Social media, especially Instagram and Tiktok, seems to further fuel people’s interest and curiosity in books. The book/reading communities in these platforms have shone the spotlight on many authors and their works. Fantasy series by Cassandra Clare, Sarah J. Maas, and Leigh Bardugo are a few examples of books social media helped popularize. Dhan Bahadur Lamsal, proprietor of Fewa Book Shop in Lakeside, Pokhara, says in the recent years he has had to tweak his business module to include promotions on Instagram and other social media. His daughters handle this aspect of the business because without promoting reading and his bookstore on social media, he might as well as shut shop permanently. “A lot of youngsters come to our store asking for books they have heard about on Tiktok. We need to be abreast of what’s popular and trending,” he says.

According to bookstore owners, the readership is primarily in English. Books in Nepali don’t sell many copies though there is a niche crowd that reads literature in our native language. Fiction sells more than non-fiction and even in fiction, fantasy seems to be the preferred genre. At any point of time, there seems to be a crowd-favorite. Ghimire says books adapted into Netflix series are widely popular. People often read the book before watching the show or if the show was good, they pick up the book expecting it to be better. Uday Agarwal of Books Nepal says collectors’ editions of such series have a good market as people want to own a piece of their favorite fantasy world.

Madhab Maharjan, owner of Mandala Book Point in Jamal, Kathmandu, says people are finally getting into reading. Many teenagers and young adults started reading during the pandemic as they had all this extra time that they didn’t want to waste. They were looking to improve their skills and learn about new things. “Today, our education system is multidisciplinary and isn’t limited to textbooks. That, I feel, has made reading compulsory,” says Maharjan.

However, he laments that ours isn’t a conducive environment for reading. There aren’t good public libraries and not everyone can afford to buy every book they want to read. Sharma of Pilgrims Book House says books have become expensive internationally after the pandemic because of labor shortage. Books that earlier used to cost around Rs 600-700 are now priced at Rs 900-1,000.

On a brighter note, there are some establishments that let people borrow books for a nominal fee. Book Corner Nepal lets you borrow two a month for a monthly membership fee of Rs 500. Sanu ko Pustakalaya in Manbhawan, Lalitpur, a memorial library founded by Priyansha Silwal, is open from 11 am to 6 pm from Monday to Saturday. You can borrow two books at a time for an annual membership of Rs 1,000, excluding a refundable deposit of Rs 500. Silwal says people seem to prefer fiction more than non-fiction. Those who read non-fiction gravitate towards self-help, books on startups, and psychology, she says. The biggest challenge of running a library, she says, is definitely preserving the paperbacks. Apart from maintaining the books, Sanu ko Pustakalaya wants to work on its children’s section as a lot of parents come searching for books for their 10-to 14-year-olds.

This culture of parents choosing books for their children worries Maharjan. “Many parents still don’t bring children into bookstores. They will buy the books for them but letting children roam around books and choose for themselves will foster a love for books and reading,” he says. Children, he adds, should be encouraged to maintain a reading journal. It will help cultivate a writing habit as well as develop their analytical skills from early on. However, Maharjan admits the change he has seen in people’s perception of books and reading is a hopeful one. People want to discover new writers and voices, he says. He believes access to the internet has made it possible for people to know about upcoming authors and prize winners. Hearing authors talk about their books makes them more intriguing, he says.

The good thing is that while earlier Nepalis had to wait a long time to get their hands on new releases, that isn’t the case now. Sharma says books used to be first published in the US or the UK and then the Indian edition would come out months later. Since Nepal gets books mostly from Indian publishers, that set us back at least a year. But now books are being launched simultaneously in the US, the UK, and India and publishers also take pre-orders which makes them available on release day or soon thereafter.

Sujan Chaudhary of Books Mantra says Nepali publishing houses are also getting the rights for popular titles and printing the books here. There are currently over 25 books being reprinted in Nepal. “We definitely have to work on the paper quality but this system has made books cheaper and more readily available,” says Chaudhary. Maharjan, on the other hand, believes the media can play a crucial role in

further popularizing books and reading. “Book reviews and discussions can spark an interest in those who have yet to discover the fascinating world that is reading,” he says.

What if… Kathmandu had more open spaces?

The earthquakes of April and May 2015 had Kathmandu valley residents running towards open grounds. For the lucky ones, it was an empty plot in their locality or a friend’s house with a big garden, while for thousands of families, places like Tundikhel and Naryan Chaur became refuge. The importance of open spaces was evident. But as things started getting normal and people moved back into their homes, land encroachment continued, leaving the city with less usable open space than ever before. If Kathmandu doesn’t prioritize creating more open spaces, a future earthquake could leave a bigger calamity in its wake, say the experts ApEx spoke to. Moreover, without enough open spaces a city also loses its aesthetic value, impacting the mental health of its residents, they add.

Suman Meher Shrestha, senior urban planner, says a city needs to be breathable and open spaces are vital for that. But uncontrolled urbanization has made Kathmandu congested, and it’s going to get worse as the population density increases. In places like Thimi, Sankhu, and Bungmati, people have realized the importance of community spaces and the local authorities are renovating and restoring old open areas like temples and courtyards. That needs to be replicated in Kathmandu too, he says, to preserve open spaces and therefore create a livable city.

Ganesh Karmacharya, spokesperson of Department of Urban Development and Building Construction, says Kathmandu valley needs at least five percent open space while currently it’s only 0.48 percent of the total area. There is an urgent need to preserve what’s there and look into ways to create additional open areas.

“Kathmandu is an old city and urban planning is a relatively new concept which is why it’s in the state it is. We didn’t give enough attention to proper city mapping,” says Karmacharya. He cites Tundikhel as an example. “If you look at old photos, you will see it was much bigger than it is today. Encroachment and haphazard construction around it has shrunk it.”

Unfortunately, the same is true for any open space in Kathmandu valley, many of which are now being used for commercial purposes. The Kathmandu Metropolitan City is constructing a view tower at the Old Bus Park. The tower is supposed to have a recreation hall, a conference hall, a museum and a library in addition to financial institutions, robbing the nearby residents of an open space. Similarly, in Pulchowk and Satdobato, Lalitpur, a couple of schools have leased their lands to businesses and departmental stores and the students don’t have playgrounds anymore.

Narayan Bhandari, deputy development commissioner at Kathmandu Valley Development Authority, says open spaces and greenery are the alveoli of a city. The KVDA is working on a 20-year masterplan to ease congestion in the valley and make it more habitable. Currently, it has identified 83 open spaces and is studying an additional 900-plus areas that can potentially be used in disasters. (According to a 2020 IOM report, only half of these sites are usable in emergencies.) The KVDA has a site in Balkumari, Lalitpur, developed with the help of Japan International Cooperation Agency, that is used to store equipment needed in case of disasters. It can also be used to house people when required.

Also read: What if… (local) elections cannot be held on time?

But while disaster preparedness is a vital aspect of urban planning in Kathmandu, Bhandari says the focus needs to be on creating multipurpose open spaces like football grounds and parks that can be used all-year-round. “These areas can be used for recreational purposes and to host various national events while also providing shelter in case of an earthquake or other natural calamity,” he says.

Experts are of the unanimous opinion that a city needs space—for children to play, elders to go on a walk and catch up with friends, and for people to just laze around. Many people live in single rooms or cramped apartments that get very little natural light and thus public spaces are also necessary for outdoor exposure. The lack of parks and public hangout locations force the youths to spend on coffee shops, restaurants and other such establishments.

If Kathmandu were to have more open spaces where people could gather, it would also foster a better sense of community, says Shrestha. Also, a designated open space within a certain radius can make even the most cramped places feel airy and pleasant. But Kathmandu, he adds, has many constraints and we need an integrated approach and different modalities to develop more open and public areas.

But Kathmandu lacks open spaces, says Arjun Koirala, urban planner and former general secretary of Regional and Urban Planners Society of Nepal. It’s just that these potential public spaces are either neglected or misused. There are also lands that can be developed into parks and playgrounds but many of these haven’t been identified yet for various bureaucratic reasons. Currently, Koirala explains, plots of land are either illegally occupied or a space looks unused but it might be private property and there is no way of knowing which is which. There are also public-private partnerships through which plots of land that should have been public spaces have been leased out. “Kathmandu valley needs a better land management system and the government can start by formally identifying which land belongs to whom,” says Koirala.

The second step would be to determine the purpose of the open area, he adds. There are different kinds of open spaces, even the ones we conventionally don’t think of as an open space. For example, wide roads and pavements are a type of open space. The Bhadrakali-Singha Durbar stretch is an open space as there are wide footpaths. People can often be seen sitting and chatting on the benches along the path. Then, in crowded cities like Kathmandu, there’s also the matter of creating open space vertically. Balconies and rooftops, in that case, also function as open space. “To create more open space, we must first decide on its requirements and then plan accordingly,” he says.

Shrestha says taking land inventory must be the starting point of the long and ambitious project of restoring Kathmandu valley’s lost splendor. Only when we know what we have can we decide what purpose it should serve and how to design it. However, he says there is also a need for proper policies and monitoring of construction projects to prevent land encroachment. There are apparently a lot of illegal structures turning Kathmandu into a denser concrete jungle.

Even though there are rules and regulations, compliance is an issue. Shrestha says more often than not construction works don’t follow approved plans. That, he says, will in long run make the valley crowded and thus aesthetically unappealing as well as unsafe. “We must not forget the valley has a certain carrying capacity and uncontrolled development will have a ruinous impact. The only way we can negate some of it is by prioritizing open spaces,” he says.

A zero-waste life: Less is more

The more we have, the more we want. But while upgrading our lives by buying better products, we are also filling our homes with things we will never use. Our hoarding habit is damaging the environment not only because we are consuming more of earth’s finite resources, but also because we are increasing our waste production.

We have inundated the Sisdol landfill site in Kakani, Nuwakot, by throwing away pretty much everything from old books and clothes to broken utensils and electronic gadgets. According to the Solid Waste Management Association of Nepal, of the 1,200 tons of garbage collected daily from Kathmandu and its surrounding areas, 65 percent is organic waste, and 15-20 percent is recyclable, meaning even that which is compostable and/or salvageable ends up in the landfill where it will take years to decompose.

The concept of zero waste, which is now almost a global movement, can help ease the landfill load and save the environment. The idea is to send nothing to the landfill by reducing consumption, composting, reusing what we have, and recycling what we can’t reuse. People around the world have reduced the amount of trash they generate in a year to fit in a single mason jar. How they do it is up for everyone to see on YouTube and other social media platforms.

In Nepal too, some are now trying to do the same. A 65-year-old lady in Pokhara, Shashi Tulachan, hasn’t produced more than a bucket of trash a year for the past eight years. “It’s possible if you are conscious about what you use and throw and how,” says Anjana Malla of Deego Nepal, a sustainable business providing eco-friendly alternatives. “The problem is many of us are into a zero-waste lifestyle because it’s become a trend and we are doing it all wrong.”

When people want to lead a more sustainable life, the first thing they do is throw away anything made of plastic. Plastic, we all know, “harms the environment”. But throwing away a perfectly good plastic container that could have lasted several years and buying a sustainable alternative in its place is counterproductive when the goal is to reduce consumption. Malla says the only way to drastically reduce waste is by cutting on what we bring into our homes.

Also read: What if… we could drastically reduce our waste?

It takes a little effort but then it’s quite easy to cut down on your purchases once you start weighing your actions and their consequences. “Don’t buy things on a whim. First look at what you have at home and see if you can repurpose things to fit your needs,” she says. And when you eventually buy new things, opt for quality stuff that will last long as opposed to something cheap that you will have to toss out after a couple of uses.

Anweeta Pandit, founder of Eco Artes Pvt. Ltd., and a zero-waste enthusiast, says we must go back to our roots and live like our grandparents and their parents back in the days. By that, Pandit means we should work on conserving resources by reusing things and only replace them when they can’t be repaired. For instance, before fancy bottles and pots took over the market, we used biscuit tins, powdered milk cans and various other jars to store grains and other essentials. We didn’t go hunting for matching glass bottles and stackable containers like we do now.

Pandit laments how zero waste is more about aesthetics today, creating more waste as we throw out everything that doesn’t match the lifestyle. “We have to be aware that our trash is a burden on the earth. We might blame industries for producing a lot of things but they are only catering to consumer demand. If there is less demand, there will be less production and subsequently less waste,” she says.

The market is saturated with products to suit different needs and tastes. Whenever we give in to our tendency to buy a new cup or a notebook when we have two unused, good ones at home, we are creating more waste. Kritica Lacoul Shrestha, senior manager at Jamarko, a company established in 2001 for environmental conservation and to provide jobs to the underprivileged, especially women, says it is imperative to change our use-and-throw culture and make our daily habits more sustainable.

We tend to disregard the effects of small, individual actions when something as urgent as the environment is at stake, she says. Instead, we blame the government for its inefficiency in tackling the waste problem. But small things like taking your own shopping bag and saying no to polythene bags or saving water while showering can add up if you do them regularly.

Also read: Kathmandu: City of Garbage

“Government policies on recycling and conservation of resources are important. But pollution is such a pressing issue that we must all do our part in reducing consumption and building eco-friendly habits,” says Lacoul Shrestha. Jamarko has been working to minimize paper waste, the long-term impact of which, she adds, will be conservation of our natural resources and habitats. Manu Karki, proprietor of Eco Sathi Nepal, a company that sells eco-friendly products, says you can start by doing whatever you can, whether it is carrying a shopping bag, your own water bottle, or taking lunch from home instead of ordering takeaway at work. The key, she says, is not to have eco-anxiety. “I have seen people try to overhaul their lives overnight and switch to greener alternatives by throwing away much of what they have. That path to a sustainable life isn’t sustainable and leads to stress and negative emotions,” she says.

A common mistake is trying to lead a completely eco-friendly life where they aren’t using anything made of plastic or entirely avoiding disposable items. There is no room for error. “There will be times when you need a single-use item like a straw, cup or a bag and that is okay,” says Malla adding you can’t let a mistake pull you down and deter you. The trick is to do what you can when you can and build on it. It should be a slow and steady lifestyle change rather than a drastic switch. “You have to understand that a zero-waste lifestyle is a process and not something you can discipline yourself into. You can never be perfect at it but you can be persistent,” she says.

Also, a complete zero-waste lifestyle isn’t practical or possible. Even if you use only what you absolutely need, you will inevitably have to discard things because of wear and tear. A zero-waste approach, however, helps you prolong the life of any object you use and thus be frugal with resources, whether it is by donating books and clothes you don’t need instead of throwing them away, or repairing the broken speakers or microwave and not buying a new one immediately. There will be things you can’t avoid but aiming for zero-waste will make you a more conscious consumer which, in turn, will translate into a lighter footprint on the planet.

Ignore the science of vastu shastra at your peril

Remember the time when you entered that beautiful hotel room and something felt off from the start? You couldn’t pinpoint what exactly, but despite the gorgeous décor and lush sheets you didn’t want to be in the room for long. Manish Nasnani, vastu consultant, blames it on imbalanced energies in the room as a result of bad vastu. Before you brush it off as superstition, Nasnani invites you to understand the science behind this age-old practice. There was a time when he too didn’t believe in vastu shastra. Only when he started understanding how scientific it actually is did he begin to find it interesting.

“People wrongly associate vastu shastra with fate and dismiss it. If you too have been doing that, it’s time to give up those preconceived notions and begin afresh because vastu shastra is actually scientific,” says Nasnani. Vastu shastra deals with subtle energy and how the placement of objects affects this energy. To begin with, consider the earth as a big piece of magnet with two poles—the north and the south. With that, everything in it becomes smaller pieces of magnets.

Manish Nasnani, Vastu consultant

Manish Nasnani, Vastu consultant

Our bodies too are bio-magnets with their own magnetic poles and magnetic fields (which we also know as aura and whose presence studies have proven time and again.) In our bodies, the part above the naval functions as the north pole and the part below as the south pole. Basic laws of physics dictate that like poles of two magnets repel each other but opposite poles attract. This is the principle that guides the rules of vastu shastra.

For instance, we are often told not to lie down with our head in the north, the reason being that the north pole of our body and the north pole of the earth repel each other. Your body spends a lot of energy in this, resulting in disturbed sleep. This apparently is believed to lead to fluctuations in blood pressure and can even cause heart problems. The risk of getting a hemorrhage or stroke goes up as well.

Our blood also contains a lot of iron and when you sleep with your head in the north direction, the magnetic pull attracts the iron which then accumulates in the brain. This is one reason a person who sleeps with his head on the north often wakes up with headaches. “Vastu shastra is all about balancing the interaction between the bio-magnet which is our bodies and the geo-magnet which is the earth,” says Nasnani.

Astrologer and expert in vastu shastra Dr Basudev Krishna Shastri, says vastu shastra is about how you can live in harmony with nature by balancing the effects of the five key elements (panch tatva)—earth, water, fire, air, and sky—that makes up the universe and everything in it, including us. Vastu shastra translates to ‘the science of architecture’ and it is basically physics. “It feels like superstition because you don’t see this energy,” he says, “but its effects are very real. The right kind of energy can fuel and recharge you, while the wrong kind can do a lot of harm.”

Also read: What lies ahead for Nepal’s LGBTIQA+ community in 2022?

The focus on living in overall synchronization with nature and not resisting its powers is one of the key principles of vastu shastra. North and east are considered positive while south and west are negative. It’s not possible or even necessary to have zero negative energy. The idea is to make sure the retaining energy in any space is positive. Nature, Nasnani says, has everything in balance and we shouldn’t disrupt this balance in the name of design.

“Everything is made up of five key elements and different corners of your house represent different elements. The north-east corner represents water, the south-east stands for fire, the south-west for earth, and the north-west for air. The space at the center where these four corners intersect is space,” he explains. According to vastu shastra, compatibility of elements is important to balance out the energies which is why the kitchen (that represents fire or heat), for example, should be built in the south-east section of a house.

The disruptive forces of imbalanced energy and elements are immense. Apparently, a vastu dosha at the Maya Sabha in Indraprastha caused the epic Mahabharat between the Pandavas and the Kauravas. The dosha was a water trench at the center of the premises, an area of the element sky that should ideally have been kept open. Astrologer Anu Kumar Jha says there are some basic principles of vastu shastra that we need to abide by in order to create better energy in our surroundings. Though there are ways of reversing vastu doshas, it’s not as practical or effective as actual synchronization of elements or energies. “Vastu shastras’ basic message is that nature will help you thrive if you let it,” he says.

Also read: Covid-19 in 2021: A year of ‘learning’ for Nepal

Experts in the field say modern medical science too has evolved to incorporate natural elements for disease-prevention. The importance of cross ventilation was made evident during the Covid-19 pandemic. Our bodies produce Vitamin D as a result of sun exposure. The vitamin is essential for proper functioning of the immune system, brain and nervous system. Our circulatory system works the way it does because of the earth’s geo-magnetic energy.

Recent studies have confirmed that our brain is sensitive to orientation, position, and direction in space and that the brain physiology is different in different directions. And, much like medical science, vastu Shastra—a part of the Veda’s scriptures believed to be four to five thousand years old—is constantly evolving as practitioners discover new things. “So, to disregard a branch of science based on thousands of years of experiments and learnings can work to your disadvantage,” says Jha.

The reason why vastu shastra is sidelined or is considered quack science is because people don’t understand it, adds Dr Shastri. The goal of the vastu principles is to create a well-lit, properly ventilated, and aesthetically designed living space that can bring a sense of peace and calm. There are thus logical reasons for everything that vastu shastra mandates. For example, big trees at the main entrance of a house are considered bad vastu as they block sunlight and the roots can damage the foundation of the walls.

As energy is primarily thought to originate from the north-east corner, many rules are derived keeping this basic idea in mind. Nasnani says our lives are governed by multiple factors, many of which aren’t in our control. Rather than stressing about the things we can’t change, we can focus on the one thing we have complete control over to create a favorable environment for ourselves, and that is vastu shastra.