Our growing obsession with jewelry

Thirty-five-year-old Shreya Rana doesn’t wear much jewelry. It’s not something she is particularly fond of. Even at family functions and other events, all she usually has on are the things she wears on a daily basis: Two silver rings (‘lucky charms’ she has had since college) and her simple ruby-and-diamond engagement ring. If she’s in the mood for it, she might add a pair of small earrings. She doesn’t feel the need to be all decked up in millions-of-rupees worth of gold and diamonds but that, in a family where people buy new jewelry to match every outfit and occasion, makes her a misfit. She says she can feel the contempt when her relatives pointedly look at her neck and ears. “Jewelry, I feel, has always been a representation of our economic status. It’s taken as a measure of success, which probably explains our obsession with it,” she says.

Nepal imported Rs 11.12 billion worth of gold in the first quarter of the current fiscal. Manik Ratna Shakya, president of the Federation of Nepal Gold and Silver Dealers Association, says even at approximately Rs 93,000 a tola, Nepalis’ interest in gold hasn’t wavered. Gold and diamond jewelry are safe investments and our culture, he says, also promotes the popularity of gold. There are many rituals and occasions that mandate the use of the precious metal as it’s considered auspicious, he says. Different cultures also require special types of jewelry for various purposes so people buy them without hesitation. It’s also a case of people wanting to upgrade their lifestyles. In the hierarchy of needs, luxury items like gold and diamonds occupy the top of the pyramid, he says, and when people have money, it’s natural for them to want more than the basics.

When ApEx questioned some people who were shopping for jewelry in New Road, Kathmandu, most were found to be either looking for something new because they had some money saved up or they were there to exchange old items for trendier ones. Rabi Krishna Shrestha, one of the directors of Asri Jewelers Pvt. Ltd., says swapping pieces one had bought earlier for newer designs or bigger items is common. Most customers they get fall into that category. “I think that’s the appeal of jewelry. You will always get your money’s worth,” he says. Rashmi Tuladhar, 48, says she buys jewelry for herself now and then as she wants to have a sizable collection by the time her son and daughter are of marriageable age. “If I ever need a substantial amount of cash, I can always sell my jewelry,” she says. Tuladhar wanted to buy a gold choker, similar to what Deepika Padukone apparently wore during one of her wedding functions.

Rosy Shakya, proprietor of Lidhansa Lun Jyasa in Pulchowk, Lalitpur, says people’s preference for jewelry has always been largely driven by trends and what their family and friends wear. There was a time when everyone had to have a diamond broach. Now, layered neckpieces are all the rage, and the bigger they are, the better. “Earlier, bridal wear could be made with two to three tolas of gold. Now people are opting for a minimum of five tolas for a single set. We have also been commissioned to use 10 tolas of gold. If people have money, there seems to be no limit on how much they are willing to spend on jewelry,” says Rosy.

Karna Shakya, owner of Taremam Jyasa, near Rosy’s jewelry store, says he sees a lot of competition among families over who is spending how much on gold and diamonds. It isn’t unusual for people to want to outdo one another and wear the bigger or better necklace or earrings. That, he feels, is one of the driving forces behind people’s growing interest in jewelry. Though business surges during Teej, Dashain, and the wedding season, there is always a steady trickle of customers throughout the year, he says. People also bring in small gold items like rings, studs, and chains that they have lying around at home to the shop to extract gold from it and make a single statement piece. The focus, jewelers in the valley agree, is on large, stylish pieces and rarely ever on old, traditional designs. Jewelers ApEx spoke to say people are more likely to come searching for an item they saw someone wear at a wedding or on TV or social media like TikTok. Personal preferences are cast aside in favor of trends.

Thirty-eight-year-old Samrakshya Karki loves wearing jewelry. A sizable chunk of her salary, she says, goes in buying diamond neckpieces, colored stone earrings or gold ornaments every Dashain or Tihar. At other times too, she makes little purchases—a diamond ring here, a gold chain and pendant there. She says she gets her love of ‘gahana’ from her mother, whose accessories always had to perfectly match her sarees. Rana remembers her parents buying new ones for weddings and other elaborate social functions and now she finds herself following in their footsteps. “The best thing is you get to wear these beautiful accessories and you aren’t wasting your money either,” she says. Karki, however, has a lot of friends who don’t wear jewelry. They choose to invest in land, shares, and bonds. “Just because they don’t buy and wear jewelry doesn’t mean they don’t have the financial means to do so,” she says. “But our culture has become so warped that if you aren’t wearing big baubles, you are automatically placed in the lower rungs of the society.”

Also read: Are dietary supplements necessary?

Unfortunately, many people don’t pay enough attention to proper styling of these baubles and that takes away from their charm, says Rosy. She often sees people wearing accessories that don’t go with their clothes. Wearing too much—a heavy necklace, dangly earrings, and fancy bangles—can make individual pieces lose their allure. Young people are also wearing a lot of gold and diamond accessories these days, perhaps cajoled into it by their parents, she adds, and that can be off-putting.

“Jewelry seems to have no age bar but that shouldn’t be the case. We have become so embroiled in an economically competitive culture that we are disregarding aesthetics and what’s proper,” she says. Rana adds that she has seen children with heavy gold bracelets, chains, and even pendants pinned to their shirts. It horrifies her, she says, to think that parents have extended their insecurities onto their children. “I believe the purpose of jewelry is to make the wearer look and feel good. It’s supposed to have a physical and emotional allure. But today it seems to be a way to flaunt your wealth and make the gap between the haves and the have-nots more vivid,” she says.

Are dietary supplements necessary?

Nepalis have always had a thing for trends. Our wardrobes mimic the styles of celebrities like Deepika Padukone and Katrina Kaif. We host gender reveal parties and plan elaborate baby showers for our friends, just like in the US. The trends we follow are usually harmless, albeit ridiculous sometimes. Health and fitness trends, however, are another matter altogether. They often have far-reaching consequences. Today, more Nepalis are buying and consuming different kinds of nutritional supplements than ever before. Many take multivitamins, omega-3s, biotin, or consume protein shakes on the reg. Experts ApEx spoke to say the trend might be unnecessary, and also a bit risky.

Anushree Acharya, dietician and MD, The Nutrition Cure Nepal, says people are popping vitamins like chocolates these days and it worries her. She says the Covid-19 pandemic made everyone conscious about health and fitness and while that’s a good thing, many have taken things too far. People buy huge bottles of fancy vitamin and mineral supplements with no understanding of when and how to take them.

Anushree Acharya, Dietician/MD, The Nutrition Cure Nepal

“What we need to understand is that a healthy person can get all the required nutrients from a proper, well-balanced diet,” she says. It’s only when you have some pre-existing conditions or a specific requirement to fulfill that you need additional nutrients in the form of pills, she adds.

Dietician Deependra Bhatta says supplements aren’t a replacement for a good diet. Many people don’t pay attention to what they eat and take health supplements like omega-3s and various vitamins to make sure their body’s requirements are being met. It’s become the easy way out, he says. Rather than basking in the sun, which we all know is the best possible source of Vitamin D, we choose to pop a pill. But food-based nutrition is better than relying on chemical formulations. It isn’t difficult to get the required nutrients from food either, says Bhatta. “For example, it’s not necessary to take iron supplements. Just add spinach to your diet. Iron needs Vitamin C for absorption and for that, you can squeeze some lemon on your food,” he says. Similarly, instead of having fish oil for omega-3s, you can include fish, cabbage, beans, walnuts, cashews, chia seeds, flax seeds, and berries among other food items in your daily diet.

Suraj Rawal, proprietor of The Protein Shop, says we have become so trend-driven that if someone we know is taking a dietary supplement, we too buy it without knowing whether it will suit us. Nikhil Tuladhar, marketing officer at E-pharmacy, says they often have to ask people buying multivitamin gummies whether the person they are buying it for has diabetes. It’s shocking how many people are unaware that there’s sugar in gummies, he says. Tuladhar has also had to deal with some parents who want to give multivitamins to their children from a young age. Despite the label in the kid’s multivitamin bottle clearly stating that it’s meant for children over two, there have been some customers who have insisted on buying it for their one-year-old. “It’s just vitamins, what harm can it do?” seems to be the general mindset, he adds.

Also read: Nepal: A country drowning in alcohol

Experts say it’s not possible to stay healthy by consuming supplements alone. That awareness is lacking in most people today who want a quick fix or to balance out their bad eating habits. A bad diet and then a handful of vitamins don’t cancel out each other, as much as you wish to believe they do. “Good health is a combination of four elements,” says Rawal. “It’s the result of proper diet, exercise, rest and supplements.” People should be attuned to how they are feeling and understand that their body is unique—meaning what works for their friend might not work for them.

But that isn’t the case, as is evident by the burgeoning online businesses selling all kinds of nutritional supplements. Pharmacies too have started stocking up on supplements because of their high demand. Multiple pharmacies in Lalitpur claim they have as many people coming in to buy supplements as prescribed medications. Tuladhar says people are mostly aware of the benefits but hardly ever of the contraindications. From what they have heard of and read on YouTube and other social media platforms, most seem to have come to the conclusion that supplements are necessary if they want to stay fit and prevent diseases.

However, Acharya says taking supplements without determining whether you need them can do more harm than good. It’s a waste of money too because the imported brands of supplements aren’t cheap. The best thing to do, she suggests, is to get a medical evaluation to figure out what nutrient you are lacking in and tweak your diet. You only need supplements when your daily intake of nutrients through food is inadequate and the inadequacy manifests in some form.

Tasnina Karki, Dietician

It’s also important to note that supplements come with a fair share of possible side effects. Dietician Tasnina Karki says there is a limit to how much vitamins and minerals you can take and consuming too much, for a long time, can lead to health issues. Excess of vitamins, especially fat-soluble vitamins like A, D, E, and K, and certain minerals can be toxic. For instance, overconsumption of Vitamin A and E leads to raised intracranial pressure that can mimic symptoms of stroke.

Consumption of large doses of Vitamin A can cause liver damage. If a pregnant woman consumes higher doses of Vitamin A than required, it can lead to birth defects in the fetus. Bhatta adds that supplements can cause annoying side-effects like dizziness and nausea in some people while in others it might lead to increased blood pressure. “Having supplements for a long time also weakens your digestive system,” he says.

Before supplements get a bad rap, Aarem Karkee, dietician at Patan Hospital in Lalitpur, clarifies that our diet today definitely lacks certain nutrients because the way food is grown and produced has changed. The soil quality today isn’t as it once used to be, so plants grown in that soil won’t have as many nutrients as it’s supposed to. We construct artificial ponds to keep fish and our cooking techniques, like steaming for too long or deep frying, ensures loss of nutrients.

Aarem Karkee, Dietician, Patan Hospital

So, in a way, supplements have become necessary. But it’s important to consult an expert to figure out what supplements you need and not randomly take anything and everything available in the market. “Dieticians can work with you to fix your lifestyle and prescribe the supplements you need. That way you will get all benefits while having to deal with none of the risks,” he says.

Chaos on city roads

Kathmandu’s roads have always been used as dumping grounds or storage spaces for construction materials. Bricks, mortar, cement, and rods line many main streets and inner alleys alike, making driving or even walking on those roads difficult, if not impossible. Often, you can’t take your bike or car out of the house because the road is blocked off by construction happening in the area. If that weren’t enough, there are always electrical poles, water and sewage pipes and piles of telephone or internet wires taking up permanent space on almost every other road. That’s just how it is, we tell ourselves, and find alternate, albeit longer or inconvenient, routes for our daily commutes.

But nothing that obstructs the road or causes inconvenience to the public is allowed, says Shiva Prasad Nepal, spokesperson at the Department of Roads (DoR) under the Ministry of Physical Infrastructure and Transport. Problems arise when everybody is doing their own thing with blatant disregard for what’s allowed and what’s not, he says. At any point, the roads, even inner streets, should be clear for easy movement and passage of vehicles. Unfortunately, that’s not the case in Kathmandu. There have been instances of ambulances not being able to reach people’s homes because their streets were obstructed by multiple mounds of gravel and sand.

“In many places, wide roads have narrowed while narrow roads have gotten narrower,” says Nepal. “People are using roads as extensions of their homes, where they park their cars, dump garbage and store construction materials for long stretches of time.” Then there’s also the issue of the Nepal Electricity Authority not removing old poles and wires, and the Kathmandu Upatyaka Khanepani Limited (KUKL) not blacktopping roads after digging it up to fix pipelines. This, Nepal says, obstructs and damages our city roads. He says the DoR has MoUs with various authorities like the NEA and KUKL allowing them to potentially use roads for their works. The deal is that whoever digs up or carries out maintenance work on roads has to restore them to their original state.

However, that’s not been the case, says Nepal, and that the DoR receives quite a few complaints about roads being dug up and left in muddy heaps, or electrical poles left in the middle of the street. DoR, he says, writes a letter to the concerned department requesting them to attend it but that is the extent of what they can do. “We can only hope they will keep their word, cooperate and fix the roads they have worked on,” says Nepal. Out of the 1,600 km of roads in the valley, only 440 km is under the DoR and they are only responsible for expansion and repair of these roads. The rest, the spokesperson says, falls under the jurisdiction of different municipalities and development boards.

Sunil Kumar Das, undersecretary at the Ministry of Water Supply and Sanitation, says it is KUKL’s responsibility to make the roads ready to be blacktopped after digging up. They don’t have the expertise to rebuild the roads. Conflicting statements from the concerned authorities suggest there is a lack of coordination and thus no clear-cut course of action, causing further disarray when there are inevitable constructions or renovations. But SP Sanjib Sharma Das, spokesperson of the Metropolitan Traffic Police Department, says nobody can use the road in a way that troubles others. You can’t block roads for weddings or construction. It’s not unusual for people to put up with road blockages because everybody knows Kathmandu is congested and there isn’t much space. How are you to build a house if you can’t bring and store the materials required for it on the road?

But Das says the law doesn’t allow that, and that there is a solution. Construction work can be carried out at night, from 8 pm to 6 am. That way, the bricks, sand and other stuff can be used up before it’s time for vehicles to move about. SP Das says that is what’s happening in his locality near HAMS Hospital in Mandikhatar, Kathmandu. After the superintendent’s repeated requests not to block the road with construction materials thus hampering vehicular movement, work now happens during off-hours and the road is clear during the day.

Also read: Nepal: A country drowning in alcohol

“If you have trouble moving about because of construction in their area, you can dial 100 or 103 and the police will come and get it cleared,” says Das. The police, however, don't resort to action or punishment in this case. They will only explain to the workers and owners of the property that they shouldn’t be troubling others. And in most cases, it works, says Das. “You don’t have to suffer the consequences of somebody else’s actions. Just be proactive and alert the authorities,” he says.

The problem of road obstruction apparently only arises when property owners opt for a labor contract instead of approaching construction companies that also manage other aspects of construction—environmental, social, traffic, health and safety. Kashin Dotel, senior project manager at Tundi Construction Pvt. Ltd., says a labor contract is mostly focused on cost minimization and profit maximization and that leads to many problems. “Since you pay per trip to bring in bricks and cement, you usually bring more than what is needed and dump it on the roads,” says Dotel. This doesn’t happen when a construction company is involved in a project. “We only bring as much as we need for a single job or go for ready-mix concrete that can be delivered to the site when needed or which takes very less preparation time. It ensures nothing is left lying around in public spaces,” he says.

Dotel’s colleague Asmit Pokhrel adds that there are many challenges that need to be taken care of before starting a construction project. A proper plan and company-client agreement are needed to ensure construction is carried out in a professional manner, with little to no harmful or troublesome impact on workers and public alike. “Construction companies plan everything before starting a project, finding additional space to store materials. That helps mitigate issues like traffic obstruction,” says Pokhrel. And when that’s not the case and issues do arise, DoR spokesperson Nepal says people can lodge a complaint at the DoR or with the police and, rest assured, it will be sorted.

Nepal: A country drowning in alcohol

Those who enjoy a drink will always find a reason to grab a bottle on their way back home from work, or make a quick detour to indulge in a peg or two at their favorite bar. Maybe there is something to celebrate—a raise or a praise, or you’ve had a hard day at work. Life is too short to wait for the weekend, isn’t it? With alcohol available anywhere and everywhere—from that innocuous tea shop to your local grocery store, drinking has become normalized. So much so that non-drinkers often find themselves explaining why they don’t drink.

Spokesperson of the Nepal Police, Basanta Bahadur Kunwar, sees the need for urgent regulation of alcohol sales in Nepal. The rampant selling and buying that is the norm today is harmful, leading to many social ills and perpetuating crimes, he says. There are many cases of domestic violence stemming from alcohol abuse, and that’s true in urban areas as well where people are educated and aware. “Something has to be done to limit alcohol consumption. We could start by allowing alcohol to be sold only in special pocket areas,” he says.

Our society has plenty of underlying stressors. Though it would be wrong to pin the blame on alcohol, often, as something that gives you a false sense of control or dampens your senses, it aggravates problems. Pinky Gurung, president of Blue Diamond Society, says many people of her community have attempted suicide after drinking. Just four months ago, a transgender died after drinking alcohol for two weeks straight when her partner left her. Alcohol consumption, Gurung adds, has worsened many people’s physical and mental health.

“It’s no secret that alcohol affects your senses and you are more likely to make rash decisions while drunk. Many times, that has fatal consequences,” says Gurung. Regulations and monitoring of alcohol sales and consumption could potentially save lives and create a safer society. One reason for the government’s failure to make proper rules regarding this is because liquor sales account for 11.8 percent of its direct revenue, says Arun Sigdel, owner of The Sanepa Madira Store, a liquor shop, in Lalitpur. The figure goes up to 34 percent when indirect revenues are added. Nepalis, he says, buy 11,000 liters of alcohol a day (and that is not counting unlicensed sellers and local ‘raksi’).

Also read: Are we losing interest in Nepali books?

“The impression our suppliers abroad have is that Nepalis drink a lot. The folks at Johnny Walker are surprised that we consume so much scotch,” he says. The reason for this, he says, is definitely easy availability. The more you drink, the more you want to drink and when there is a store selling liquor right next to your home you will be tempted. Mishlin Gurung, cashier at Green Line Center, another alcohol store, in Kantipath, Kathmandu, says drinking is also trendy among the youth. It’s a fad that doesn’t seem to go out of style. She sees a lot of people in their 20s buying liquor and there is a pattern to it, she says. “They usually drink what everyone else is drinking. The general mindset is that you have to drink to be cool,” she says.

Pooja Thapa, owner of Binayak Liquor Shop in Ekantakuna, Lalitpur, says Nepalis are drinking more than ever before and that the liquor business is a highly profitable one. Though she didn’t disclose how much liquor is sold on a daily basis, she said it was definitely on the higher side. One could say the store has a customer or two at all times. No wonder why new liquor stores have popped up all over Kathmandu. In Ratopul, what used to be a clothes retail shop and a place selling mobile accessories are now fancy liquor stores. Shisir Thapa, founder of Cripa Nepal, an alcohol rehabilitation center, says there was a tea shop near the center that wasn’t doing well but business boomed after it started selling alcohol.

Thapa says Nepalis are at a high risk of alcohol abuse as it is available everywhere and anyone can access it. There is no oversight on who is selling alcohol and who is buying it. This has been creating many problems in our society but the government remains oblivious. “Imagine how bleak the situation is when there are alcohol suppliers right next to a rehabilitation center where people are struggling to overcome alcohol addiction,” he says.

The government had solid plans to curtail alcohol sales and consumption—from maintaining distance between two liquor shops to selling only at fixed hours—but like much else, they have been limited to paper. The only action ever taken was a ban on alcohol advertisement, promotion and sponsorship when the government passed a National Policy on Regulation and Control of Alcohol in 2017.

“Even that one rule hasn’t been followed. You can still see open advertisements of alcohol in the guise of event promotions and such. The government has been negligent in this regard,” says Thapa. Plans to regulate alcohol sales in Nepal never come to fruition because “alcohol in itself is politics,” says Bishnu Sharma, CEO of Recovery Nepal, the umbrella organization of rehabilitation centers in Nepal. Sharma says their repeated lobbying for policies to regulate alcohol sales in Nepal have failed—and how. Manufacturers of liquor have lobbied harder and used their higher-up contacts to foil their efforts. The government, citing high revenue from liquor and tobacco industries, has refused to do anything to curb sales.

Minesh Rajbhandari, co-founder of Cheers, an online liquor store, says there needs to be a proper system to control and monitor alcohol sales. The government shouldn’t be giving out any more licenses and should monitor the ones who are in the business to ensure they aren’t selling to minors or evading taxes. “We could learn a thing or two from how India is managing its liquor industry,” he says.

Our culture promotes drinking and that makes it worse, adds Sharma. He cites a study from Rasuwa district that found that the main cause of abject poverty was alcohol. Every ritual demanded alcohol and people took out hefty loans to provide the same to families and friends. Sharma says his organization ran some programs to change this situation and the results have been positive. What Nepal needs is many more of such interventions. “Our effort in Rasuwa is just a symbolic gesture. The government has to come forward to tackle the social ills brought about by alcohol consumption,” he says.

The state, he believes, is being hypocritical. First it allows people to drink but when there are inevitable brawls and fights and people pass out on the road, they are taken to the station and locked up. Stricter laws and proper enforcement of those laws are what’s needed. “You can’t allow something to thrive like the way it has allowed the liquor industry to and then tell people to be responsible adults,” says Sharma.

Sharma, much like every other person ApEx spoke to, isn’t calling for a blanket ban on alcohol sales and consumption. Everyone thought there were many cultural and religious sentiments to take into consideration but they agreed that we must also think of the cost addiction puts on a nation and its economy. “Alcohol is a part of many cultures and religious festivals but that doesn’t mean there shouldn’t be rules to control its use,” says Sharma. “The key here lies in proper regulation and policies to tackle the effects of alcohol abuse.”

What if… the domestic help industry were regulated?

Domestic helpers are becoming an integral part of urban Nepali households. Without them, a huge chunk of our lives would be consumed by menial chores, leaving little time for work, date-nights, books and Netflix. In Kathmandu, families, young couples and even single working professionals rely on maids for smooth running of their homes. Despite providing such essential service, domestic helpers are paid very little, are often abused verbally and/or physically, and worse, the work can sometimes be humiliating, with their employers asking them to clean dog poop or fix a clogged washroom drain.

This wouldn’t be the case if there were a system that regulated domestic workers, says Prakash Basnet, founder of Help2Shine, a service that connects domestic helpers to households. The challenges that domestic workers face right now are mostly related to lack of rules or laws to standardize their pay-scale, work-hours, and job description. The general attitude is that maids need to do everything they are asked to because housework entails many different things. According to Nepal’s labor force survey 2017/18, there are over three million women in the labor market. A report titled ‘Domestic Workers, Risk and Social Protection in Nepal’—by Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing, a global research-policy network—estimates there are 250,000 domestic workers in Nepal.

“It’s a booming informal sector and it has to be regulated. But that won’t happen unless the government steps in and makes provisions to systemize it,” says Basnet. The Labor Act of 2017 specifies that the government can set a separate minimum wage for domestic workers but nothing has been done so far. Help2Shine is trying to change how domestic helpers are hired and put to work by making both parties sign a contract stating time and work requirements and negotiating a salary based accordingly. But private companies can only do so much when the government isn’t involved. The contracts, after all, have no legal standing. It’s more of a moral obligation—and that, Basnet says, is easy to disregard.

Also read: What if… the MCC compact is not endorsed?

Thirty-three-year-old Shobha Budathoki who has been working as a domestic help in Kathmandu for eight years says theirs is a thankless job and employers don’t value them. What upsets her the most are the empty promises and assurances people dish out while hiring them. She says it’s common to be told their work will be evaluated and they will be given a raise accordingly in six-months’ time. But Budathoki has worked at the same place for several years without even the mention of an increment. It’s unfair but that’s how things are and there is nothing we can do, she says.

“If the government were to make rules that determined how domestic helpers should be employed, that would make things easy for both the employer and the employee,” says Basnet, because contrary to popular belief, it’s not just domestic helpers who are facing problems at the moment. There are instances where employers are blackmailed and manipulated by their house help as they feel they are indispensable. If the government set up a system to hold both the employers and employees accountable, like in any other professional setting, it could foster a mutually beneficial environment.

Over at City Maids Services Pvt. Ltd. founder Kishori Raut says bringing this informal sector under its wing would be a good source of revenue for the government as well. There’s a lot of untapped potential here, says Raut. That aside, people would become liable for their actions and there would thus be fewer issues. “Problems arise as there is no professionalism at either end. A government body regulating the sector would take care of that. People would have to behave a certain way,” says Raut. Budathoki adds that new regulation could also guarantee job security such that employers wouldn’t be able to fire them over a trivial argument.

Apart from the fact that a lot of issues would either disappear or there would be sensible ways to fix them, the government’s involvement would also make domestic workers feel validated and valued. Raut says the domestic workers registered at his company often refuse to have their pictures taken or request anonymity as they don’t want their close ones to know they are in this line of work. “There is a certain stigma associated with domestic work and the government making rules for it would be the first step to normalizing it,” says Raut.

Also read: What if… sanitary pads were made free?

The government stepping in and paying attention can help bridge the gap between the employers and domestic help—make both parties aware of their rights and responsibilities. It will also establish a professional setting where there is dignity of labor. The problem today is that people often want their domestic help to be subservient. With no rules on what they can and can’t do, many suffer from the ‘master-complex’, getting away with pretty much anything.

Rajan Joshi, company representative, Wipe Maids and Cleaning Services, says lack of a system leads to exploitation. It’s not unusual for his clients to want to pay as little as possible. The company he says is trying to fix a baseline salary of Rs 10,000 a month for a four-hour job-day but that hasn’t been well received. Joshi says the resistance is understandable given that people have been hiring maids for as low as Rs 2,500 to Rs 3,000 a month for years now.

“It’s inhumane to expect them to work for that price today because they won’t be able to even feed their families,” he says. By setting rules and regulations and determining the minimum wage the government could improve their situation. “Domestic workers deserve to be paid decently, if not handsomely, but that isn’t the case right now. The government has to pay attention to them. It would help tackle the issue of poverty besides giving both parties involved a place where their complaints are heard and addressed as and when they arise,” he concludes.

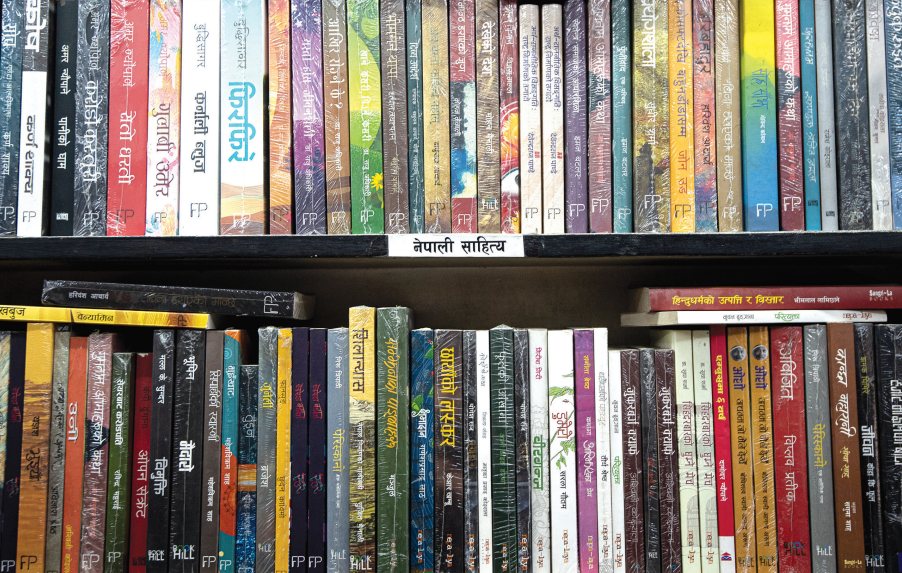

Are we losing interest in Nepali books?

Hom Nath Bhattarai, spokesperson of Sajha Publications, the oldest publishing house in Nepal, is of the view that Nepali literature isn’t as deep and meaningful as it used to be during the time of Laxmi Prasad Devkota or Parijat. This, he says, could be because readers today prefer entertainment over introspection and publishing houses have had to cater to that. However, the strategy hasn’t really worked in the Nepali market—there still aren’t many people reading Nepali books, at least not enough to make publishing a viable business or for Nepal’s literature scene to flourish.

“There was a time when books had social messages. They were lesson- and value-oriented. The audience was mostly academics and those who believed reading was crucial for intellectual growth,” says Bhattarai. Generally, youths in Nepal weren’t reading much back then. Bhattarai believes Narayan Wagle’s ‘Palpasa Café’, a story about an artist during the civil war in Nepal, published in 2005, changed that. It was what got Nepali youths interested in Nepali novels. Palpasa Café had a simple, moving premise and characters youths could relate to. After that, the publishing industry saw a surge of authors telling relatable stories, trying to pull in that crowd.

Chandra Siwakoti of Pairavi Book House agrees that there was a phase when youth-centric and love stories by Buddhi Sagar, Amar Neupane, and Subin Bhattarai, to name a few, made youngsters gravitate to reading. But social media soon took over and that trend quickly died. The Nepali publishing industry is struggling today as the market is small and there are, he says, far too many writers. “During the Covid-19 lockdowns, everyone was writing something or the other because suddenly they had all that free time,” says Siwakoti. “We got so many submissions in the months that followed.”

However, Bhattarai and Siwakoti both believe quality writing is hard to come by, and that publishing houses today have had to compromise on quality to survive. Bhattarai also laments the new trend of self-publishing. He doesn’t think these self-published books will add value to our literary scene because without proper editors and publishers working on multiple drafts of a book, a writer can only bring so much nuance into the work. “As a writer you can’t be critical of your work. That’s why self-published titles are often rough drafts of what could have been good books,” he says.

Also read: Fixing Kathmandu’s chaotic roads

Bringing out a good book requires the expertise and effort of many people, says Bhattarai. So, it helps if new and even experienced writers have the backing of a publishing house. Bhattarai says the publishing house FinePrint has been trying to promote—and to an extent succeeded in promoting—new writers and Nepali literature. He says it seems to have new ideas on how publishing can become a profitable business. From introducing lightweight paper to publishing a wide range of books, FinePrint has been at the forefront of the publishing industry—trying out new tricks of the trade to sustain the book business.

Ajit Baral, co-founder of FinePrint, says their focus is on good editing, design, and layout. He, along with Niraj Bhari, started FinePrint because he was passionate about reading and writing. They didn’t think of it as a business. It was what earned them a good name and trust among readers and writers alike. That, in a way, has also helped them persevere when things have been rough like during the Covid-19 pandemic when work came to an absolute halt. Baral says they are still trying to recover from the setback. “It’s only a matter of time, I hope,” he says.

Not just FinePrint. Things are far from easy for everyone involved in the publishing business. Chiran Ghimire, manager at Himal Books, says it sometimes takes a year to sell even 1,000 copies of a really good work. This he attributes, in part, to people reading more on digital platforms as opposed to buying physical copies of books, which can be expensive. But the main reason is that people’s aptitude for reading has been on a decline for quite a while. Siwakoti of Pairavi Book House says it has been steadily dwindling in the past seven years. Pairavi has been sustaining itself by focusing more on publishing legal books which, being compulsory reading for many, has a solid market. “We haven’t been publishing a lot of literary works as Nepalis aren’t reading all that much,” says Siwakoti.

When a new Nepali book comes out, there is generally a lot of buzz on social media. But that doesn’t necessarily lead to a spike in sales, say those in the industry. Kalpana Dhakal, CEO of Kitab Publishers, says there was a time when reading and publishing were at their peak. When Sudhir Sharma’s ‘Prayogshala’ and Hari Bansa Acharya’s ‘China Harayeko Manchhe’ were published in 2013, they were well received and did good business as the market was booming. That, she says, isn’t the case anymore.

Also read: Misogyny in Nepal: Little acts, big consequences

In the course of doing market surveys before the launch of her company Dhakal spoke to various booksellers who confessed they didn’t sell as many copies of Nepali books as they did before. Even the classics, for instance books by BP Koirala and Parijat, aren’t in much demand. Books written in English on the other hand, they said, did relatively better. “I’m new in this business so I try to find out how others are doing. Everyone in the publishing industry seems to be on the same boat. We are all barely sustaining ourselves,” says Dhakal. She feels unemployment (hence no compulsion to read and learn) and a variety of entertainment options are the main reasons why reading isn’t a culture in Nepal and that doesn’t give her the confidence to publish more than two to three books a year. It just isn’t a wise business move. But Dhakal is hopeful of a brighter future because societies need to grow and for that reading and writing are essential.

Bibash Shrestha, sales officer at Kathalaya, says there is a need to explore different ways to make reading an inescapable part of people’s lives if the publishing industry is to thrive. With that in mind, Kathalaya did workshops and community-level literature festivals in the past. They also translated different language books into Nepali to expose people to a wide array of authors and works. Publishing houses, he says, should do a lot more than publish books to make theirs a viable business.

Writer and historian Sujit Mainali adds that the only goal shouldn’t be to come out with bestsellers. It’s important for authors to write on topics they are well versed in. Bhattarai says some books, despite not having mass appeal, are important to document the culture and history of a community or a place, and these books need to be published even if they aren’t commercially viable.

Baral, on the other hand, sees the need to tap into the e-book market. The problem, he says, is that individual publishing houses don’t have the resources to invest in something that won’t give immediate returns. Those in the business agree that collaborative efforts could also be a way forward. Siwakoti says publishers could start by having more discourses to figure out what kind of writing they should promote and how to do that. “We are responsible for creating and maintaining the quality of Nepali literature and it’s time we took that seriously,” he says.

Fixing Kathmandu’s chaotic roads

Kathmandu traffic is the stuff of nightmares. Besides not reaching your destination on time, you are also likely to get into a squabble with someone on the road. There might be a rash motorbike rider who will squeeze through from the wrong side bumping onto your side mirror, or a pedestrian that you luckily miss by an inch when he suddenly jumps on the road from the sidewalk. On good days when none of that happens, there will be a traffic police who is infuriated you didn’t stop when he signaled you to. You will tell him his partner on the traffic island was gesturing wildly for you to speed up but he will either verbally abuse you or write you a ticket. Either way, you suffer.

Kathmandu residents claim commuting here is frustrating, to say the least. It always leaves you in a bad mood, they say. Sometimes you feel walking might be a quicker, a comparatively hassle-free alternative as opposed to taking a bus or a private vehicle. At the most, all you will have to navigate are the potholes and weirdly jutting out bricks and broken pieces of mortar. It’s the lesser of the two evils. But it’s not a feasible solution.

SP Sushil Singh Rathore says the problem of congestion in Kathmandu can’t be attributed to one particular reason. SP Rathore cites people’s unwillingness to follow traffic rules and laws as one of the major causes of chaos on the roads. Apart from that, there are other infrastructural issues that need to be addressed for better vehicular movement and management.

“Many things slow traffic movement. Vehicles stop and park randomly on the roadside, there are street vendors on the footpath that force pedestrians to walk on the road, and there aren’t proper signs and lane dividers—what you call road furniture,” says SP Rathore. Then there are construction materials and garbage piled high here and there on the main roads as well. The public, he adds, is quick to blame the police. But the approximately 5,000 police personnel deployed to manage the valley’s traffic are doing the best they can, he assures. Manually managing traffic isn’t ideal but there’s really no other option at the moment.

Rathore says the city needs more flyovers and subways to accommodate the increasing number of vehicles. He cites the example of the 800-meter underpass in Kalanki between Khasi Bazaar and Bafal Chowk and how that has significantly lessened traffic hassles in the area. Another issue is lack of parking spaces. Road expansion, in many areas, didn’t ease traffic congestion because vehicles are parked on both sides of the now-bigger roads.

This past week, the Bhat-Bhateni Supermarket launched its fully automated vertical parking at its outlet in Tangal, Kathmandu. The first-of-its-kind 11-storey parking system in the country can accommodate 44 four-wheelers. Rathore says Kathmandu city in particular needs more parking lots or smart parking systems that make use of vertical space. Only these kinds of long-term solutions will help better regulate the valley’s traffic.

However, DSP Santosh Rokka, Metropolitan Traffic Police Department, says they are looking into ways in which traffic niggles can be fixed. There are currently 39 traffic lights up and running and there are plans to install 11 more. Rokka believes this will significantly ease road congestion in places where nobody stops for others and vehicles end up colliding or getting stuck at junctions. Then there’s the question of broken traffic lights that haven’t been fixed, like the one at the Kupondole-Thapathali junction that perhaps sees the most traffic after the Koteshwore-Lokanthali stretch, especially during rush hours.

This, Rokka says, is out of their hands because the police haven’t been given the authority to maintain them, and neither does the concerned department look into it. The police, he says, have to make do with whatever is in working order. The problem is that the police shoulder all the responsibility but have zero authority in management and decision-making. Meaning, they get the blame but none of the credit. There are technical glitches all the time and the traffic lights stop working suddenly. To ensure that doesn’t lead to havoc, multiple traffic police personnel have to be stationed at each stop all the time.

The authorities say they are aware that the public has a lot of grievances with the traffic police. That is why, Rokka adds, they take feedback and complaints seriously and, based on them, include discussions on how to improve their handling of traffic during their daily morning briefing. We are committed to doing better, he says.

Also read: There is no quick fix to Kathmandu’s flooding

“But most of our problems stem from people’s recklessness on the road,” says DSP Rokka. He says the department has to station police even in places where the traffic lights are fully functional as people tend to disregard the signs when they don’t see anyone in a blue uniform around. There have been quite a few accidents when drivers haven’t stopped at the red light.

DSP Dhundi Raj Neupane asserts people aren’t disciplined on the road. Sensible drivers are a rare breed, he says. As much as we’d like to believe otherwise, we are all in a little hurry the minute we step outside. We don’t make way for anyone, sometimes not even for ambulances and emergency vehicles. DSP Neupane says we are all guilty of blaming everyone but ourselves. Each one of us, he says, is a part of the problem. The sooner we accept that and look into our own actions, the faster we can solve this steadily worsening traffic condition.

SP Prajwal Maharjan agrees that the biggest challenge is people’s unwillingness to wait and follow the rules. There are over 3,000 daily traffic violations and the majority of these are motorbike riders driving in the wrong lane. We might have infrastructural liabilities but it’s possible to work around those issues. The city, he says, isn’t getting any bigger. We know what we have and so we need to adjust accordingly, while the government comes up with long-term plans and solutions.

“It’s as simple as stopping and letting another vehicle pass to clear the way for you rather than trying to go first and getting stuck,” says SP Maharjan, who also suggests heading out 15 minutes earlier than usual to not be in a rush. That will be a little extra effort on our part but, adds Maharjan, given the limitations, it can make a lot of difference.

Misogyny in Nepal: Little acts, big consequences

Social media can be both entertaining and infuriating. And often there is a thin line between the two. Memes and elaborate jokes about women and their habits are by nature misogynistic but, sadly, men usually don’t realize how offensive and derogatory their posts can be—that something ceases to be a joke when it’s at the expense of another person’s dignity.

Recently, a high-ranking official at a renowned media house in Nepal posted a picture of his wife on Facebook. Propped up in bed, surrounded by tissues, pills, and bottles of water, with a hand massaging the bridge of her nose, it was clear that she was unwell. The caption read something along the lines of ‘The wife has all the symptoms of Covid-19 except loss of smell and is incapacitated. The husband’s daily routine suffers.’ The original text, in Nepali, rhymed. The husband obviously thought he was being clever. The post has been removed but it was a hauntingly good example of how the society still largely perceives its women—as those whose lives are best lived on the fringes of men’s wants, ambitions, and idiosyncrasies.

Senior journalist Ruby Rauniyar says our societal structure is such that women are made to feel less important and valued than men. That is, she says, the reality in many educated, well-to-do families too. There are covert ways in which women are sidelined and treated like the weaker sex. If a daughter is strong, confident, and does well in life, she is called the son of the family. The implication being that men are the heroes and women can rarely, if ever, match up.

“Misogyny starts at home when we differentiate between our sons and daughters, when we have different sets of rules for them because of their gender,” says Rauniyar. Change isn’t easy because we have grown up seeing our mothers bend backwards for their families and fathers being unappreciative of the efforts their wives put in to keep the household running smoothly, often without them lifting a finger.

Also read: Why make Rangoli in Tihar?

Our society’s misogynistic mindset is further fueled by the inequality and unfairness that women bear with in order to maintain peace at home. When women stay silent to avoid conflict, despite their feelings being hurt, they reinforce the superiority complex that most men have grown up with. Psychologist Minakshi Rana says we unknowingly nurse the male ego and give men a false sense of power when we don’t express ourselves.

“That is why I say you shouldn’t let go of the little things. If you have an issue, speak up. Women are usually guilty of letting things slide. By not holding men accountable for their words and ways, you let them think they are right,” she says. Rana adds that it’s appalling how misogyny often goes unnoticed until the little things add up and become too big to contain. Most domestic issues and relationship problems she has seen in her career stem from men having gotten away with things for far too long till women couldn’t take it anymore. “From then on, a simple joke becomes a taunt and you can’t fix that kind of equation,” she says.

There’s no denying that our society undermines its women. It’s sometimes glaringly obvious in the form of violence while other times it hides behind the façade of jokes and traditions. The subconscious belittling of women is perhaps the worst form of torture you can inflict on them. At most homes and parties, the men eat before the women. After a long day at work, the men demand tea and it is the wives who go to the kitchen, having just put their bags down, to fix it and then start preparing dinner. When a husband does the dishes after the wife cooks, he is ‘helping’ her.

Also read: Nepal’s decennial census needs a rethink

Rauniyar says women are responsible for all the chores men consider mundane. “If there is a family function or a gathering at home, the women are expected to take a day off from work. The men come home just in time to party,” she says. Most things women do—laundry, dusting, grocery shopping—are considered her duties. She receives no appreciation for it because ‘she is supposed to do it’ and ‘how hard can it be’. Rauniyar narrates an incident she witnessed where the father-in-law berated the daughter-in-law for allowing her husband to work in the kitchen. He said seeing his son cook was humiliating and asked her to handle kitchen work entirely on her own.

Usha Shah, retired as SSP, Police Hospital and currently serving as chief dietician at Grande International Hospital in Kathmandu, says women are dominated everywhere in the world and it’s not something that’s specific to our culture. What’s different is that in many other countries, women are pushing back. Here, we are still so entrenched in patriarchy that many women accept sexual discrimination as their fate, something they have to deal with because their mothers and grandmothers did and taught them to.

As bleak as it sounds, there is no light at the end of the tunnel in this case, says Counsellor Geeta Neupane of The Women’s Foundation Nepal. She says even those who harp about equality in public platforms have this narrow mindset about women and their position in society. Neupane blames years of conditioning for that. It’s not something that’s easy to shrug off, she says. Worse, even women believe they are second class citizens. “If you don’t, then you have to act like it,” she says.

Subservience is expected of women because they are women. No matter how educated men are it doesn’t stop them from exercising that socially- and culturally-granted right. Rauniyar says she has seen doctors and engineers—those we have placed in the highest rung of the social hierarchy—not treating their wives as partners and always imposing their decisions on them. Neupane adds men have a sense of authority that has been handed down through generations. However, that is not to say that there aren’t men who don’t rise above social norms. But they are rare, not to mention people constantly tease them for doing women’s work. “Only some men, the ideal ones, are able to let go of that inflated sense of self and treat women as equals,” says Neupane.