Five ropeways for human transport and almost a dozen gravity goods ropeways are in operation in Nepal. Ropeways are an ideal mode of human and goods transport for Nepal’s hill- and mountain-dominant terrains. Their potential, however, is yet to be fully realized. Reports suggest that the country could have ropeways in nearly 2,000 areas and feasibility studies have been conducted in 62 places. But to install a ropeway for people transport in Nepal, an investor has to get approval from 21 different government authorities.

“We’ll not attract investors unless our bureaucratic hurdles are simplified,” says Guna Raj Dhakal, chairperson of Ropeway Nepal Pvt Ltd. Installing ropeways is six times cheaper than building roads and the maintenance cost is also low. The 42-km Hetauda-Kathmandu Ropeway, for instance, cost half as much as the Tribhuvan Highway on the same route to build. “Yet the government is still skeptical about ropeways,” adds Dhakal. “We don’t even have a dedicated ropeway department or policies for that matter.” When CPN (Maoist Center) joined mainstream politics after signing the Comprehensive Peace Accord in 2006, the party committed to installing around 50 government-run ropeways in its first election manifesto. The party has been in almost every government since, but the old promise is yet to be fulfilled.

Haribol Gajurel, the party’s deputy general secretary, blames political instability for this state of affairs. “Our party led the government only twice and only for short durations,” he says. “We were unable to work on our plans.” He says ropeways are still on the list of his party’s priority projects.

Tulsi Gautam, spokesperson for the Ministry of Physical Infrastructure and Transport, says the ministry is well aware of the ropeway’s potential in Nepal, and its suitability in terms of both cost and practicality. “However the government as of now has no plans to commission a ropeway project on its own.” He says it is normal for a ropeway company to get approval from many government agencies. “Even the process of obtaining a citizenship requires several approvals and recommendations,” he adds, making the case for the rigmarole of ropeway project approval.  Manakamana cable car was the first of its kind in Nepal. Manakamana Temple and nearby villages, situated at the top of a hill in Gorkha district, were an isolated place until 1998. People had to walk for almost six hours from Aabukhaireni to reach the top. But things changed drastically after Manakamana Darshan Pvt Ltd started the cable car operation. It transformed the Manakamana area by pulling in over a million tourists a year.

Manakamana cable car was the first of its kind in Nepal. Manakamana Temple and nearby villages, situated at the top of a hill in Gorkha district, were an isolated place until 1998. People had to walk for almost six hours from Aabukhaireni to reach the top. But things changed drastically after Manakamana Darshan Pvt Ltd started the cable car operation. It transformed the Manakamana area by pulling in over a million tourists a year.

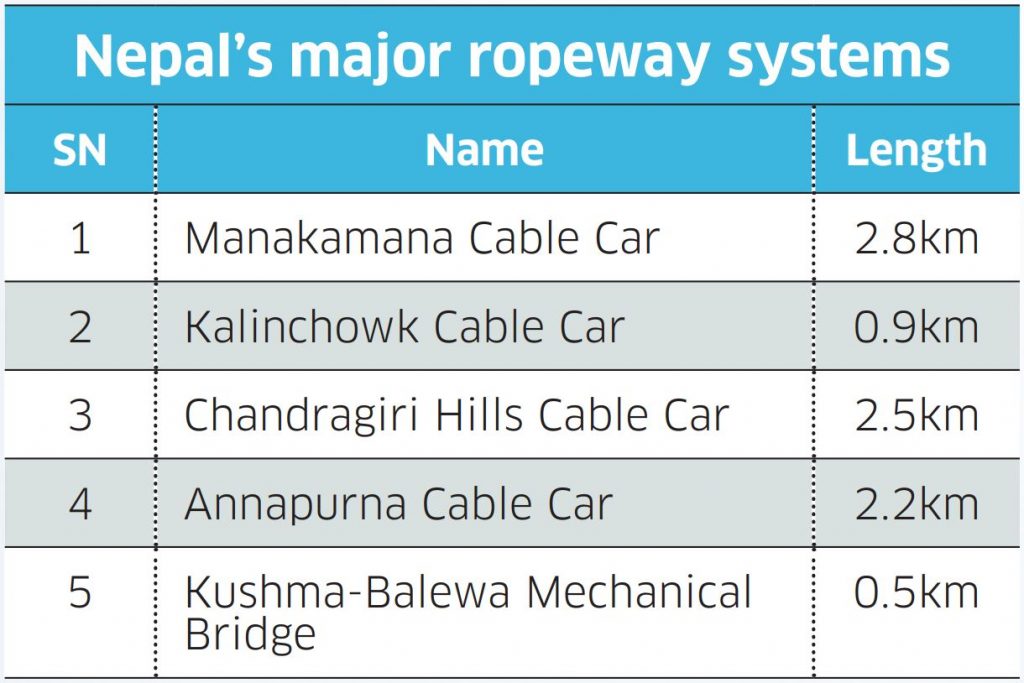

Businesses around the area flourished and many new jobs were created. “The benefits of the cable car system were not limited to people living in Manakamana area, but also touched the locals of Kurintar, Malekhu, Munglin, and even Naubise,” says Dilli Narayan Kayastha, the company’s managing director. “I have seen hotels nearby shut down when we closed for maintenance.” It took nearly two decades after Manakamana cable car for Nepal to get another ropeway transport service—Chandragiri Hills Pvt Ltd in Kathmandu, to be followed by Kalinchowk Darshan Ltd in Dolakha and Annapurna Cable Car in Kaski. All of them are privately funded projects.

Also read: Nepal’s most iconic ropeways—now abandoned

“Despite the hurdles, over two dozen cable car services are either in the process of commercial operation, construction or feasibility study,” says Dhakal of Ropeway Nepal.

IME Group, which built Chandragiri Cable Car under Chandragiri Hills Pvt. Ltd., is currently working on five additional cable car services. These include Gaidakot-Maulakalika (1.2km), Butwal Bazar-Basantapur (3km), Chisapani Highway-Rajkada (Kailali), Sikles-Kori (Kaski) and Ghantikhola-Swargadwari Temple in Pyuthan district.

Works are also afoot to start a cable car service in Pathivara Temple in Taplejung. Besides, private companies are conducting ropeway transport feasibility studies in Dakshinkali-Chaukhatdevi, Budhanilkantha-Shivapuri Hill and Bohoratar-Nagarjun Hill in Kathmandu; Godawari-Phulchowki Hill in Lalitpur; Ghorahi-Swargadwari Temple in Pyuthan; Ghyangphedi-Gosainkunda in Rasuwa; Lukla-Namche Bazar in Solukhumbu; Devghat-Moulakalika Temple in Chitwan; and Ranital-Maulakalika in Nawalparasi. Nepal Investment Board is also facilitating the study for an 84-km cable car service from Birethanti-Kagbeni-Ranipauwa to Muktinath Temple in Mustang. If implemented, the project is expected to significantly boost tourism and improve the livelihood of local people.

Dhakal says though cable cars conjure up an image of a major pilgrimage site or tourist destination somewhere in a hill or mountain terrain, they could also help address the problem of traffic congestion in city areas. “Our politicians have been pitching for metro-rail and monorail to ease Kathmandu valley’s traffic congestion,” he adds. “But I believe that the cable car system could better address the problem of urban mobility.” Ganesh Ram Sinkemana, an expert on gravity goods ropeways, has installed ropeways in various parts of Nepal, India, and Bhutan. He says gravity ropeways are perfect for transporting goods as they do not need external power to operate. “Two linked trolleys, on pulleys, run on separate wires suspended from towers. As the full trolley comes down, pulled by the weight of its load, it pulls the empty one up, ready for the next load,” says Sinkemana.

Unlike ropeways for transporting people, gravity goods ropeways do not require many approvals. Just the permit of the respective local government will do. Sinkemana firmly believes that ropeway technology will maximize the use of locally available resources and manpower, creating jobs and business opportunities. “Yet we are not building them. Our politicians are more interested in having expensive roads and bridges.”

When Kushma-Balewa Mechanical Bridge, a ropeway system, was constructed in 2013 to connect two hills of Kushma and Parbat separated by the Kaligandaki River, the four-hour journey between the two places was reduced to four minutes. Local businesspersons initiated the project after the government ignored their request to install a suspension bridge to ease the mobility of goods and people.

“The government did not help us. So we took it upon ourselves and built this ropeway,” says Hom Narayan Shrestha, chairperson of Kushma Balewa Mechanical Bridge Company. Much like Kushma-Balewa Mechanical Bridge, Kotre-Punitar Mechanical Bridge was also built without government assistance in order to connect Tanahu and Kaski.

But it was shut down following the installation of a suspension bridge. Ram Chandra Khanal, chairperson of Kotre Punitar Mechanical Bridge Company, says ropeway transport had to be shut even though many locals favored it over the suspension bridge. “If the government had supported us, we would have revived this technology as the locals are also in favor of Yantrik Pul instead of suspension bridge,” says Khanal.