At the United Nations, Nepal has presented an ambitious plan of achieving net-zero carbon emission by 2045. In addition, it has pledged before the international community that, come 2030, 15 percent of its total energy will come from clean sources and 45 percent of the country’s forest cover will be maintained.

These targets can only be achieved if the Nepal government secures sufficient funds for its adaptation and mitigation measures. That is why Nepal has made it clear that its climate commitments are contingent on funds from international organizations.

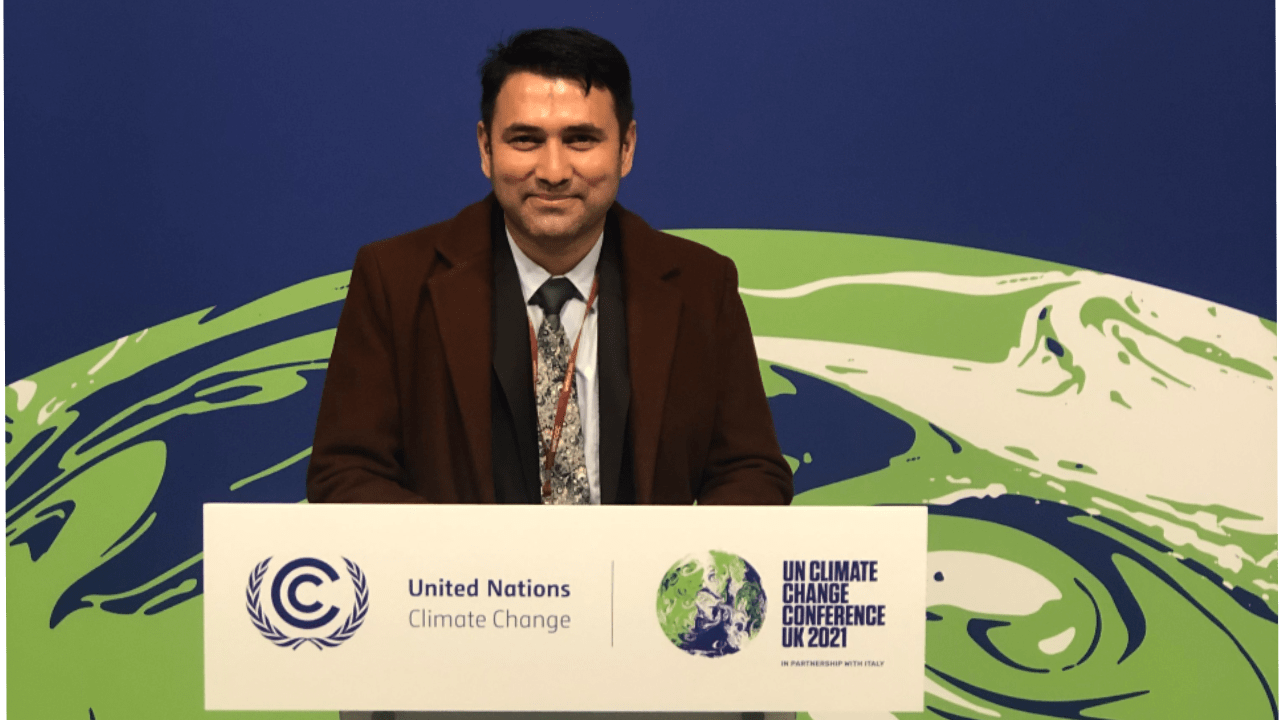

At the recent COP26 summit in Glasgow, Scotland, Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba was clear that Nepal could deliver on its goals “only through quick, direct, and easy access to climate finance”. The country thus urged the international community to agree on a clear roadmap for a new collective, quantified and ambitious goal on climate finance before 2025.

After the finalization of the climate change budget code in 2012 in order to track allocations to climate change related projects and programs, the Nepal government has since 2013 set aside money under ‘climate change’ in its annual budget.

In addition, Nepal has been lobbying for funds from various bilateral and multilateral organizations to implement adaptation and mitigation measures and reportedly, it is already getting ‘millions of dollars’ even though exact figures are hard to come by. But there is a lack of transparency in the climate budget. Irrespective of the budgetary provisions, in the absence of dedicated mechanisms, it has been hard to track income and expenditure.

Also read: ‘ApEx for climate’ Series | Nepal makes its case. But to what effect?

There is a related problem as well. Even though both government and non-government agencies are implementing dozens of programs to address climate and environmental issues, it is difficult to isolate expenditure on climate issues in the absence of an exact definition of ‘climate expense’.

Says climate change watcher Manjeet Dhakal, money is being spent in specific areas of climate change but also on other indirectly linked areas. For instance, a few years ago, the government had allocated Rs 3 billion for the purchase of electric vehicles with the goal of reducing the emission of greenhouse gasses, says Dhakal.According to him, even though the Ministry of Forest and Environment is the focal ministry, other government agencies are also allocating budgets on climate-related issues. Compared to the past, there is greater awareness on climate change in government agencies, and thus also on the need to allocate budget for it. In addition, government agencies are starting to adopt sustainable development models.

But current budgetary allocations are not sufficient to achieve net-zero by 2045, which the government aims to do by increasing the use of renewable energy.

Nepal submitted its second Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) to the United Nations under the Paris Agreement. In the NDC, Nepal has committed to a slew of measures to reduce carbon emissions and launch adaptation and mitigation actions. An estimated $25 billion is required to meet the targets—and hence the conditional clause in the NDC.

Also read: ‘ApEx for climate’ Series | Nepal in the middle of a climate crisis

To get support, the Fifteenth Plan (2019-2024) talks about ‘advocating at the international level for easy access to climate finance and distributing any potential benefits to provincial, local, and community levels.’

Similarly, the Climate Change Policy introduced in 2019 states that “national resources will be identified for the implementation of climate change-related policies, and all resources will be mobilized in a just manner by increasing access to bilateral, multilateral, and international financial resources pertaining thereto.”

Climate finance involves many actors and agencies like government bodies, development partners, UN agencies, multilateral development banks, I/NGOs, local institutions, corporate houses, and user groups.

Specifically, Nepal can get financial support from multilateral international financial mechanisms such as REDD+, Green Climate Fund, Global Environment Facility, Adaptation Fund, Climate Investment Fund, and Carbon Trade. Similarly, it can and has been getting funds through various bilateral mechanisms in sectors like agriculture and forest.

“The private sector actors for their part can invest in climate via initiatives under their corporate social responsibility,” says Dhakal.

Also read: ‘ApEx for climate’ Series | How does Nepal get help in tackling climate change?

But at the end of the day Nepal and other LDCs will have sufficient money for climate action only if developed countries fulfill their commitments. In the Copenhagen Accord signed in 2009, developed countries pledged approximately $100 billion by 2020, which was not delivered. The Paris Agreement 2015 reaffirmed the commitment, but also to no avail.The Paris Accord says, “As part of a global effort, developed country Parties should continue to take the lead in mobilizing climate finance from a wide variety of sources, instruments, and channels, noting the significant role of public funds, through a variety of actions, including supporting country-driven strategies and taking into account the needs and priorities of developing country Parties. Such mobilization of climate finance should represent a progression beyond previous efforts.”

At COP26, developed countries again pledged to meet the old target by 2023.

Nepal’s own budgetary allocation for climate has been steadily increasing, and today all three levels of government have yearly climate budgets.

There is also a question over how the three tiers of government are spending their climate funds. The country’s climate change policy provisions for mobilization of 80 percent budget for local-level climate programs by reducing administrative expenses. The policy also states that there will be appropriation of the budget for women, minorities, backward class, climate change affected areas and vulnerable communities.

Yet a large portion of the climate budget, say the critics of the current arrangement, is being spent on meetings and seminars in Kathmandu rather than on the ground. “For our climate initiatives to be effective, around 80 percent of the climate budget should be spent at the local level,” says climate journalist Mukesh Pokhrel. “But a far smaller share goes to local bodies right now.”

Also read: ‘ApEx for climate’ Series | Putting Nepal’s gen-next in climate lead

The federal government in Nepal appropriates 60 percent of the total budget while local governments get only 20 percent. The provincial governments, for their part, get 12 percent.Nepal has pledged with the international community to formulate climate finance strategy and national capacity on climate finance management by 2022. Homework on this has begun but progress has been patchy. Till date, there is no mechanism in Nepal to exclusively handle climate finance. There is a separate ‘climate change’ division under the Ministry of Forest and Environment but experts say a separate body is needed to coordinate with other government agencies.

In recent years, the government has launched some specific programs targeting climate change. In 2021/22, the Nepal government launched a carbon emissions reduction program in 13 districts of Tarai Madhes including Rautahat, Bara, Parsa, Chitwan, Banke, Bardiya, Kailali, and Kanchanpur.

In the fiscal year 2020/2021, it started research programs on forest, plant resources, wildlife, biodiversity, watershed, environment, and climate change in coordination and partnership with universities and research institutions.

More than that, there is a need to decentralize the climate budget and take it to the grassroots where the most adverse effects of climate change are felt. At the same time, local governments should be empowered to deal with climate change issues. “But most of the money is being spent in administrative and non-productive areas. There should be a thorough review of what we are doing,” advises Pokhrel.

Nepal’s priorities don’t match the donors’

Ram Chandra Bhattarai, Economist

We are spending less than three percent of our Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in the climate sector. Climate finance is basically what donors give us. It is donor-guided and as such their interests prevail. We basically need finance for our adaptation measures.

We are more responsible for adaptation than mitigation. Nepal does not contribute to climate change but faces most of the related problems. Yet there is little international support on adaptation. We are doing adaptation mostly on our own; most of the help we get from abroad goes into mitigation, which is the donors’ interest.

Donors are investing in alternative energy but that is not our number one priority right now. They are not providing pure climate finance—just transferring money already allocated to other sectors.

We are making a lot of noise on climate change and climate finance but there has been little progress. Even our usual expenditure has been clubbed under ‘climate change initiatives’. For example, the money we are spending on the preservation of our forests. When it comes to actual spending on climate change, there is little of it.

Five questions to Manjeet Dhakal

Achieving net-zero emission is not difficult for Nepal

Though Nepal is recognized as one of the most vulnerable countries to climate change, there is little in terms of preparation for a possible climate crisis, or in mitigation measures. How can we be better prepared? And do we have the money and other resources to pursue climate initiatives? Pratik Ghimire of ApEx talked to Manjeet Dhakal, a student of climate change who is also the Head of the LDC Support Team at Climate Analytics.

What is the current status of the effects of climate change in Nepal?

Many reports have suggested that Nepal is highly vulnerable to climate change. This is also because temperatures here are increasing faster compared to other parts of the world. Erratic rainfall has destroyed our crops, leading to an agro-based job crisis. Moreover, climate change has caused floods and other disasters, and destroyed vital infrastructures like the Melamchi Water Project. This has put added strain on our already stretched economy. Effects of climate change also depend on a country’s economic status. Well-off countries can take up measures to build resilience. As we can’t afford that we are forced to bear the brunt of climate change.

Can Nepal achieve net-zero emissions by 2045 as promised at COP26?

I don’t think it is going to be difficult as there has been a massive development in climate technologies. We now can, for instance, switch to electric vehicles instead of petrol and diesel ones. That would substantially reduce carbon emissions. As Nepal has only a handful of industrial sites, we can easily electrify the new factories. The government is aiming to increase forest cover to 45 percent of the land by 2030. Hopefully, the goal can be achieved. Nepal imports around Rs 200 billion worth of petroleum products a year. We can channel that money in the development of electric machinery instead.

How do you see Nepal’s climate diplomacy?

I find it progressive and reform-oriented as we are frequently invited to climate change-related international summits and given the chance to share our data and situation. That said, it is not easy for a small nation to maintain diplomatic relations, especially on climate issues, given our limited resources.

Also read: Bishal Nath Upreti: There is no quick fix to Kathmandu’s flooding

Is the international community turning a blind eye to our mountain agenda?

I don’t think so. If you go back to the recent COP26 summit, Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba presented our agenda and the international community responded positively. There are some failed projects too. But we have to look at our mistakes first. They had shown an interest in Sagarmatha Sambad as well, but we couldn’t push it. The best thing that happened at COP26 is that we didn’t ask for help, we rather shared our initiation and progress. Prime Minister Deuba has committed to organizing Sagarmatha Sambad and let’s hope he means it.

Moreover, it is technically difficult to extract data from mountain regions, which might have been looked upon as ignorance. But it is the same for other nations who raise mountain agendas. We get a good response otherwise.

How can Nepal get enough climate finance for adaptation and mitigation?

We have to find international funding for that, and to an extent, we are getting that too. No nation provides funds easily, so we have to convince them with our vulnerability reports, data, commitments, obligations, and authentic process and progress. A decade ago, developed nations had pledged $100 billion annually to the least developed nations to fight the climate crisis. But the pledge has not been met. Yet, compared to others, we are among the countries that get good international funding on climate issues.

We can also do our bit by reducing the import of petroleum products and using the saved money as climate finance. By doing that, first, we will greatly reduce our trade deficit, and second, greater use of electric machinery will also help us clean up our environment. Separately, if we can cut down the import of petroleum products by only five percent, we can provide Covid-19 vaccines to every Nepali.