Bandarjhula settlers caught between wildlife and wily politicians

Inhabitants of Bandarjhula, located in the middle of a forest in Madi Municipality-9, have for years been asking for land-ownership certificates. But their demands have fallen on deaf ears.

Interestingly, the issue of land ownership makes its way to the top of political parties’ agenda every election season. Around 700 registered voters in this place are assured of certificates during elections but the promises are soon forgotten.

Former Coordinator of Bandarjhula struggle committee, Rajkumar Praja, says many promises of land certificates since 1998 have gone begging. “The government allocates the budget, and another government agency stops it. And if our votes are legal, how can our lands be illegal?” he asks.

CPN (Maoist Centre) Chaiman Pushpa Kamal Dahal and CPN-UML Chairman KP Sharma Oli had reached Madi with the agenda of party unification ahead of the last federal election in 2017. From the same podium, the two leaders had promised to address the problems of the residents of Bandarjhula—again to no avail.

Dahal, who has been frequently visiting Madi, last month reached Bandarjhula and expressed his worry over the issue. However, he is silent even as the National Park and Wildlife Conservation Act 1973 poses a hurdle to their land-ownership. Bandarjhula lies in a wildlife corridor. The act bars development and farming in such a corridor. Government officials say the place is not appropriate for human settlement.

This place lies in Chitwan election constituency-3, which Dahal won in 2017. In July 2020, Former Prime Minister Oli had claimed that Madi is the birth place of Lord Ram. Attempts are now being made to popularize Bandarjhula as Hanumanjhula.

Also read: Covid-19 in 2021: A year of ‘learning’ for Nepal

Before the last federal elections, another charismatic Rastriya Prajatantra Party leader Bikram Pandey was elected from here. The current provincial chief of Lumbini Province, Amik Sherchan, had become deputy prime minister after being elected from the same constituency. Prior to that, Nepali Congress leader Narayan Sharma became the Minister for Water Resources, and his predecessor Tirtha Bhusal is also from Madi.

Madi has elected many politicians who went on to hold influential positions, and the country has turned into a republic, but the plight of Bandarjhula inhabitants remains unchanged. The settlements are yet to be electrified and the Chitwan national park has been obstructing development works in the ‘transgressed’ or ‘captured area’.

The majority of people living in this place are from Chepang, indigenous and Dalit community. People from Makwanpur, Parsa, Lamjung, and Tanahun, among other districts, migrated to Bandarjhula which now has 660 households. Prior to this, Nepal Army personnel used to live there. Landless squatters moved in after the army left.

“We are being treated as foreign citizens in our own country,” says Sarada Acharya, Chairperson of Bandarjhula Struggle Committee. “All that we want is to be allowed to stay here. If that is not possible, let us be resettled in another place.”

As the demands for land ownership certificates were not heeded, the settlers had staged a relay hunger strike for four nights at Maitighar Mandala in Kathmandu. The protests culminated in a three-point deal between the National Land Commission and Bandarjhula struggle committee. The commission has pledged to provide land survey documents after completing all the required processes.

What lies ahead for Nepal’s LGBTIQA+ community in 2022?

Nepal is the first South Asian country to recognize transgenders and the first in the world to include a ‘third gender’ in its census. It’s been a decade since the ‘third’ option was added to voter rolls and immigration forms. The constitution of 2015 addresses the LGBTIQA+ community in Articles 12, 18, and 42, granting them social and political rights. But, behind the glossy façade, say the LGBTIQA+ community and those lobbying their cause, there are plenty of unresolved issues.

Bimala Gurung, program officer at Mitini Nepal, an organization lobbying for the rights and dignity of lesbian, bisexual and transgender people, says one of the main issues right now is the paucity of constitutionally protected rights for LGBTIQA+ individuals. That makes them vulnerable to exploitation and abuse, she says, which is why Mitini Nepal will focus on stronger advocacy and awareness programs in 2022—besides lobbying for more economic opportunities for the LGBTIQA+ community. “Financial instability is one of many reasons people of the community are suffering. Providing them more career opportunities could fix some of the problems,” she says.

But Bhakti Shah, transgender activist, says they are so sidelined in every aspect that it’s disheartening and stressful. He says they aren’t even asking for special opportunities, just equal chances. The problem right now is that they are disqualified from the get-go because of their sexual orientation. “You can never compete when you don’t even stand a chance,” he says. The society puts up a pretense of acceptance while silently trying to wish their existence away and that complicates things even more. One reason Nepal looks progressive on paper but lags behind in reality are the many loopholes that make rule-implementation impossible.

Also read: Nilam Poudel: Carve out space for LGBTIQA+ community in every sector

Bhumika Shrestha, vice-chairman of an organization advocating LGBTIQA+ rights, gives the example of acquiring a citizenship that, for most, is a birthright but for people of LGBTIQA+ community, it’s still a major challenge. It’s now possible to obtain a citizenship identifying as ‘others’ but there are issues that complicate the matter. The government requires a sex change operation certificate and not all can afford the expensive surgery. Many might not even want to undergo the procedure for personal reasons but it’s a compromise you must make if you want a citizenship. “So many people in our community couldn’t get the Covid-19 vaccine as they didn’t have the documents required to prove their nationality. The same thing happened when the government distributed food and other essential items to daily wage workers during the lockdowns. No identification meant no help,” says Shrestha.

Identity crisis and lack of self-worth are indeed huge issues in the LGBTIQA+ community, adds Shah. The foundation of every other right for the community lies in first establishing and accepting LGBTIQA+ identities. Everything else hinges on this, says the activist. “Once that issue is resolved, I believe we can fruitfully work on the rest,” he says. Shrestha too believes that unless their identities are firmly established, they will always be ignored. “Disasters are difficult times and it’s worse for us as we won’t get any government help. We have nowhere to go,” she says.

The citizenship issue is something the LGBTIQA+ community has been lobbying for almost 20 years, with little success, says Pinky Gurung, president of Blue Diamond Society. They are hoping the 2021 Nepal census will give them the data to finally put pressure on the government to include them in their plans and policies. “Policymakers have their own biases and agendas. They listen to us and agree to discuss things but nothing ever comes out of it. Hopefully, once we have data, we can get their attention,” she says.

Also read: LGBTIQA+ community of Nepal: Life on the margins

The inclusion of third gender in the census is a hopeful start of some really imperative changes to come. But as many families still hesitate to reveal the true identities of their children, the data might not be entirely accurate. Greater sensitivity and understanding are needed for wider social acceptance. Shrestha says the main issue is that many still don’t understand homosexuality. There have been instances of school boys being taunted and harassed for ‘behaving like a girl’. Revising our school curriculum to include LGBTIQA+ stories and such could help foster a more inclusive environment and normalize things.

Marriage equality also needs to be prioritized, agree those ApEx spoke to. Not legalizing same-sex marriage means there is a lot of uncertainty in relationships and that, in many cases, has led to domestic violence. Our patriarchal and conservative society is a breeding ground for violence and the situation is worse in the LGBTIQA+ community where relationships are fickle because of lack of legal recognition. Shah says a lot of people have had mental health issues and even tried to commit suicide after their partners left them. “People in our community feel insecure in their relationships and that often leads to misunderstandings and physical and mental abuse,” he says.

Sunita Lama, LGBTIQA+ rights activist, says change must start at home. She says she feels disheartened by the lack of change in people’s mindset. But they can’t afford to lose hope, she says, as family acceptance is important if they are to ever feel safe and worthy. In the coming year, Lama hopes there is more societal acceptance as a result of families embracing their children irrespective of their sexual orientation. “Social acceptance is the only thing that can bring about policy level changes,” she says. Lama says lack of policies is the direct result of the authorities simply not trying to understand LGBTIQA+ issues because of their underlying biases.

The LGBTIQA+ individuals ApEx spoke to say their lives oscillate between stress and fear. With the odds stacked against them and no one to turn to, every day is a struggle. They have been lobbying for their rights for so long and have so little to show for it that they have lost hope of drastic change in their lifetime. But working today for a better tomorrow, so at least the next generation won’t have to go through what they did, motivates them to carry on. In 2022, like every other year, they hope to achieve a few milestones but, in their hearts, they know it’s going to be like every other year—one step forward, two steps back.

Covid-19 in 2021: A year of ‘learning’ for Nepal

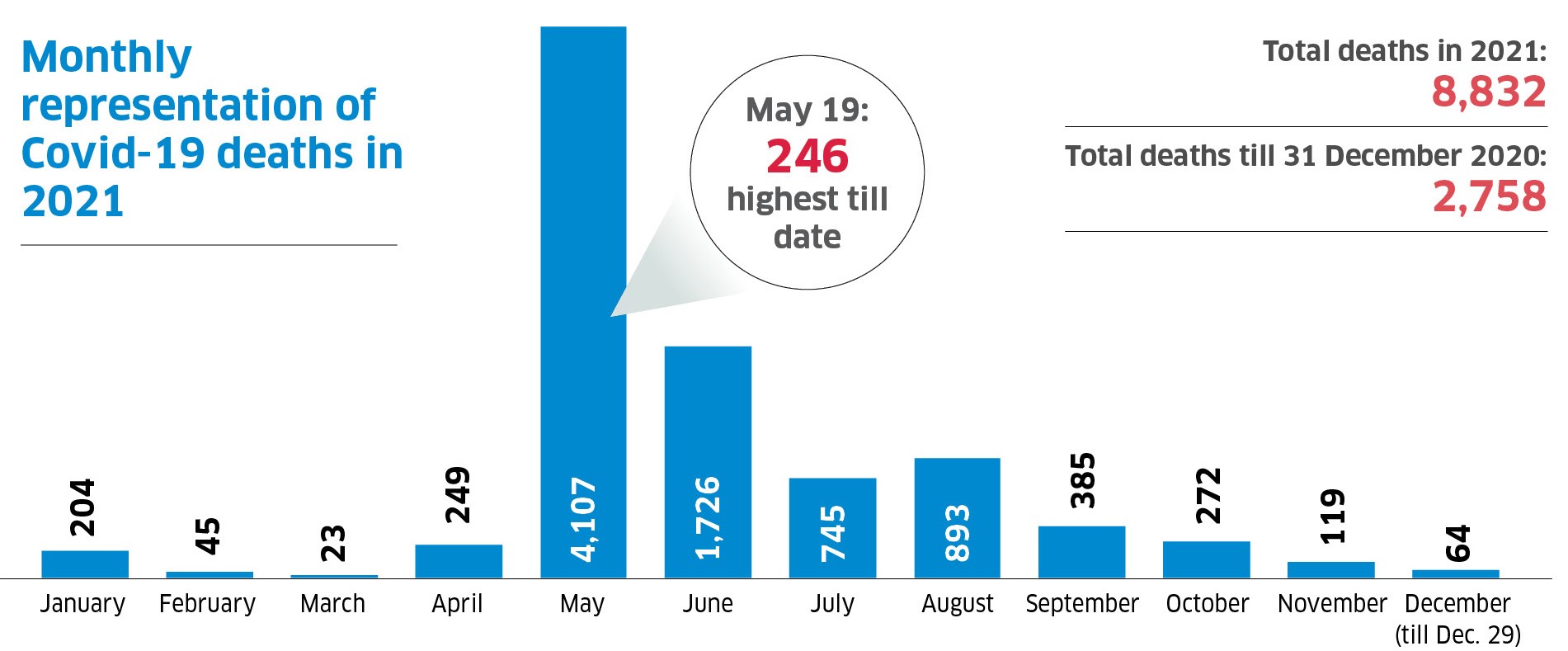

The year 2021, in a way, represents another ‘lost year’ for Nepal as all sectors continued to be deeply affected by the Covid-19 pandemic, even though there was a slight reprieve at the year’s end. As soon as the second wave hit in late April, the government, in collaboration with District Administrative Offices, imposed prohibitory orders, with varying levels of restrictions in different districts. From July, the lockdowns were gradually lifted as covid cases declined.

Due to the constant political turmoil, the Ministry of Health and Population had five different ministers in 2021. This also led to a frequent change of officials at health institutions and major hospitals, adding to the difficulties of pandemic-control.

The larger number of daily new cases and lower number of recoveries in May caused an acute shortage of oxygen cylinders, hospital beds, ventilators, ICUs, and other medical supplies. The death rate also spiked, with around 4,000 dying in the month alone. As the second wave’s effects declined, recovery rates, compared to new cases, increased, resulting in only two percent active cases (at the moment).

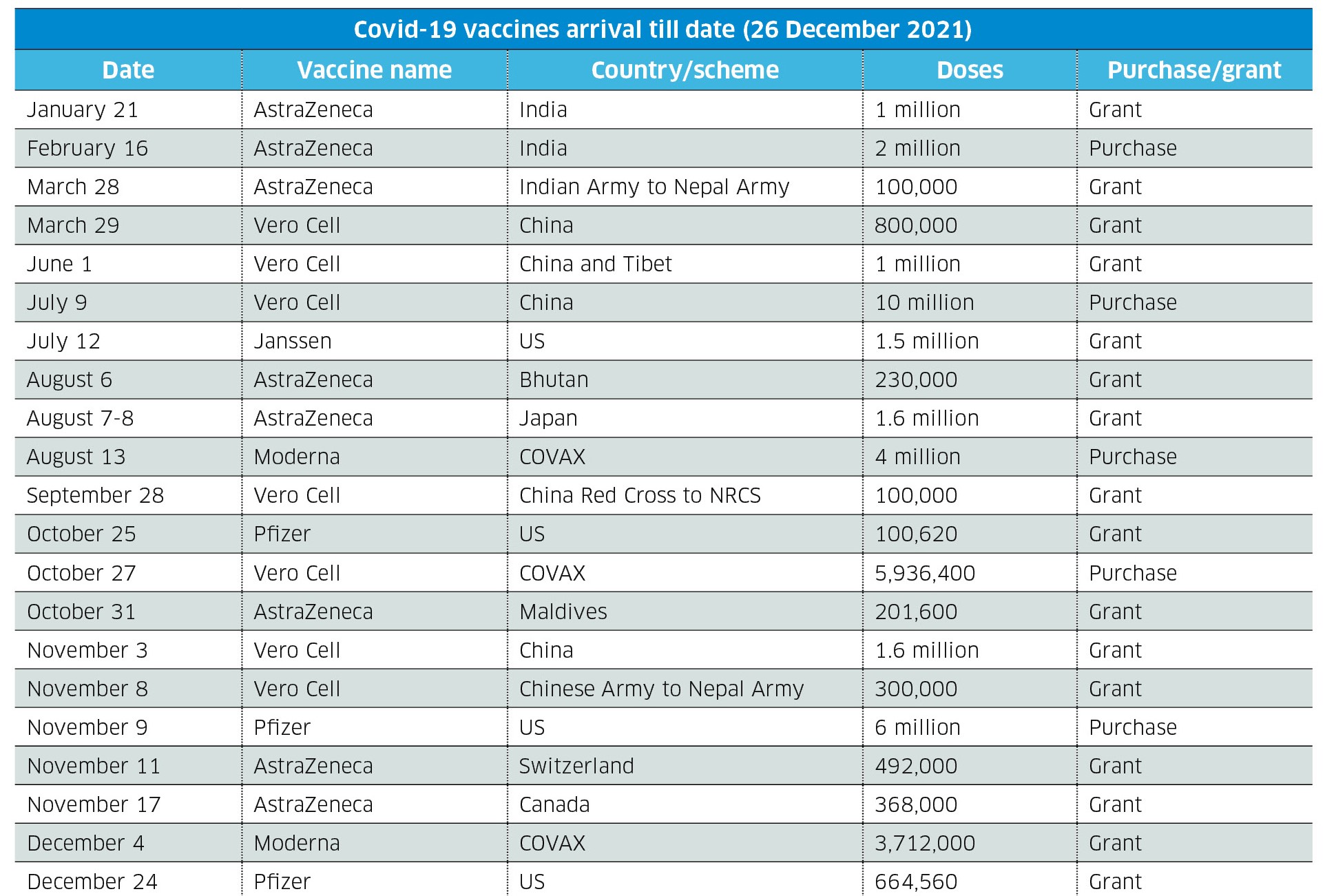

The first-ever set of covid vaccines came to Nepal on 21 January 2021, and people got their first jabs on January 27. The first delivery included a million doses of Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccines provided by India as a grant, while Nepal agreed with Serum Institute of India to buy another two million doses of the same vaccine. But the company later refused to provide the jabs, depriving almost two million people of timely second doses.

Under various vaccine campaigns across the nation, Nepal approved six types of covid vaccines but only four of them—AstraZeneca (India, Japan, Europe), Vero Cell (China), Janssen (US), and Pfizer (US)—are now being used. As of now, over 35 percent of the population of Nepal is fully vaccinated. On November 14, Nepal rolled out Pfizer to children over 12 who also is the first country in the Asia-Pacific region to give covid vaccines to refugees.

Lately, a new corona variant—Omicron—has been detected. Nepal has so far confirmed three cases of this variant—the first two on December 6 and the third on December 22. The effect of vaccination on this variant is as yet largely unknown. Moreover, a final decision on giving booster doses to the fully-vaccinated population is yet to be taken.

“The year of learning”

Dr Sangita Kaushal Mishra

Spokesperson, Ministry of Health and Population

The Delta variant was not kind to us, yet we have learned many things from this unpleasant covid journey. Everyone knows the areas in which we as a country fell behind, but here I want to focus on the positives.

The year 2021 made us prepared for the next wave—whenever it hits. We have much better medical equipment like ICUs, ventilators, oxygen plants, etc, even at the local level.

The death of over 8,000 people is something no one wanted. The general public, after the second wave, has been aware of the risks. So there has been a collective effort to minimize the pandemic’s effects. Vaccination started right from the start of 2021 and there has been good progress throughout the year. Even if the Omicron variant has now been detected, we are still, by and large, coping with the Delta variant.

Summing up, 2021 had both positives and negatives but most of all, it was a year of learning for all involved in Nepal’s health sector.

Nepal bids 2021 adieu with snow (Photo feature)

The Mountain and hill areas across the country were covered by fresh snowfall on December 29.

Along with hills adjacent to Kathmandu valley, Humla, Dolpa, Kalikot districts experienced heavy snowfall compounded by incessant rainfall. According to our correspondents, the fresh snowfall constitutes three meters thick.

According to the Meteorological Forecasting Division, light rain is likely to occur at a few places in the hilly region of the country on December 30 as well. Possibility of light snowfall at some places of the high mountainous region.

copy_20211229122726_20211229184606.jpg)

copy_20211229122728_20211229184607.jpg)

copy_20211229105026_20211229184609.jpg)

copy_20211229122735_20211229184610.jpg)