‘The Heart Principle’ book review: A fantastic read

This is the kind of love story I want to read. ‘The Heart Principle’ by Helen Hoang was so-so good. I can’t stress that enough. It was believable. It wasn’t over-the-top. I don’t particularly enjoy love stories but if they were all like this one, I would devour them and become a sucker for romance novels. ‘The Heart Principle’ is the final book in the three-book series by Hoang, the first two being ‘The Kiss Quotient’ and ‘The Bride Test’. You don’t have to read the books in chronological order. The stories aren’t connected. I haven’t read them but I have heard that they too are good. But those who have gone through all three keep saying that ‘The Heart Principle’ is the best. Anna Sun is a violinist who shoots to fame when a YouTube video of her performing on stage goes viral. But she has since been replaced by a 12-year-old prodigy and is struggling to make music. Nothing she comes up with seems to be good enough. Then her boyfriend, Julian, suggests they open up their relationship. He wants to be sure she is the person he is meant to be with. When Julian says he knows Anna won’t date anyone, she becomes determined to prove him wrong. Enter Quan, who has just recovered from an illness and is looking to get back on the dating scene. The two connect through a dating app and hit it off right from the start. But Anna’s family doesn’t approve of Quan. She has also not broken up with Julian, who her mother and sister absolutely adore. Anna isn’t the type who can assert herself, say no when she wants to. It doesn’t help that she has recently been diagnosed as autistic but her sister thinks it’s just an excuse for her ‘poor’ behavior. Hoang writes with a lot of empathy for her characters. You find yourself mentally defending even difficult characters like Pricilla, Anna’s elder sister, who tries to dictate how other people act and live and generally comes off as annoying. You see she’s driven by her desire for what she assumes is good for her family. Her intentions are right, even though that may not be obvious. There’s a lot to unpack in The Heart Principle. The book deals with trauma, grief, family pressure, and the need to conform among other things. It’s a really wholesome love story.

Fiction

The Heart Principle

Helen Hoang

Published: 2021

Publisher: Berkley

Pages: 339, Paperback

‘Kaduva’ movie review: Decent enough, but not for Vivek Oberoi

I remember Vivek Oberoi’s debut back in 2002 in the Ajay Devgn-starrer ‘Company’. Oberoi played Chandu—a rookie henchman turned gangster—in one of the most iconic Hindi gangster films. The young Oberoi not only won the hearts of the audiences and critics alike but also went on to win multiple wards for his performance, promising a glorious career in Bollywood. Fast forward to 2022 and Vivek Oberoi is no more a big name in Bollywood. His filmography is light in big banner films, which is surprising given his dashing debut. Although he has had a few commercial hits, they’ve mostly been ensembles with someone else taking the center-stage. We don’t really want to get into Oberoi’s personal life and controversies. But it’s really painful to see an actor with so much potential go almost unnoticed in the Indian film industry. Anyway, I first want to tell the audience that I watched the latest Malayalam language film ‘Kaduva’ just because Oberoi was in it—and also because Amazon Prime did not have anything more interesting to offer this week. Directed by Shaji Kailas, Kaduva is set in the late 90s in a village called Pala in Kerala, India. Kaduvakunnel Kuriyachan aka Kaduva (Prithviraj Sukumaran) is a wealthy planter who lives in Pala with his wife Elsa and three children. Kaduva is known in the area not only as a successful businessman but also as a good, church-going Samaritan who helps everyone in need and goes out of his way to punish any wrongdoing. These characteristics of Kaduva and an incident at the local church pit Kaduva against Joseph Chandy Ouseppukutty (Oberoi), the Inspector General of the region. The corrupt Joseph, backed by high ranking politicians, is one of the most powerful persons in the region. Riled up by Kaduva’s attitude towards him, Joseph lets loose a barrage of attacks against Kaduva and his family. Kaduva, the survivor that he is, fights back with full force. ‘Kaduva’ is a mainstream Malayalam movie. Meaning, rather than a strong script, storytelling and acting, there are other elements that appeal more to the mass: like the protagonist Kaduva sending policemen flying with his kicks and punches and not getting any major injuries himself no matter how hard he is hit. Nevertheless, the film has a strong script and great execution. As the protagonist Kaduva, Prithviraj Sukumaran is highly convincing. The film’s also brought out by his own production company. The actor seems to know what he is doing: the movie has grossed well at box office. But what Prithviraj and the filmmakers fail to do in ‘Kaduva’ is fully utilize the talents of Vivek Oberoi. The actor they borrowed from Bollywood has been reduced to an unintelligent antagonist who does not contribute much to the film’s outcome. Although he has been given a very powerful position in the film, his character lacks that ferocity and intelligence expected of a villain. Oberoi does try to make an impact on the screen but is limited by what’s written for him. Disappointing, as he was the reason I watched the film in the first place. Kaduva’s screenplay also leaves a lot of unanswered questions and little mysteries. It keeps the audience thinking till the very end and then in the climax, gives them a strong hint of a sequel. A clever ploy, I’d say. And I’d definitely want more of Vivek Oberoi if there’s a sequel. Who should watch it? ‘Kaduva’ is not a bad film. Overall execution is pretty decent and readers who enjoy South Indian films will definitely like it. Vivek Oberoi fans will be a bit disappointed but the sequel looks promising for his character. Rating: 3 stars Genre: Action, drama Actors: Prithviraj Sukumaran, Vivek Oberoi Director: Shaji Kailas Run time: 2hrs 35mins

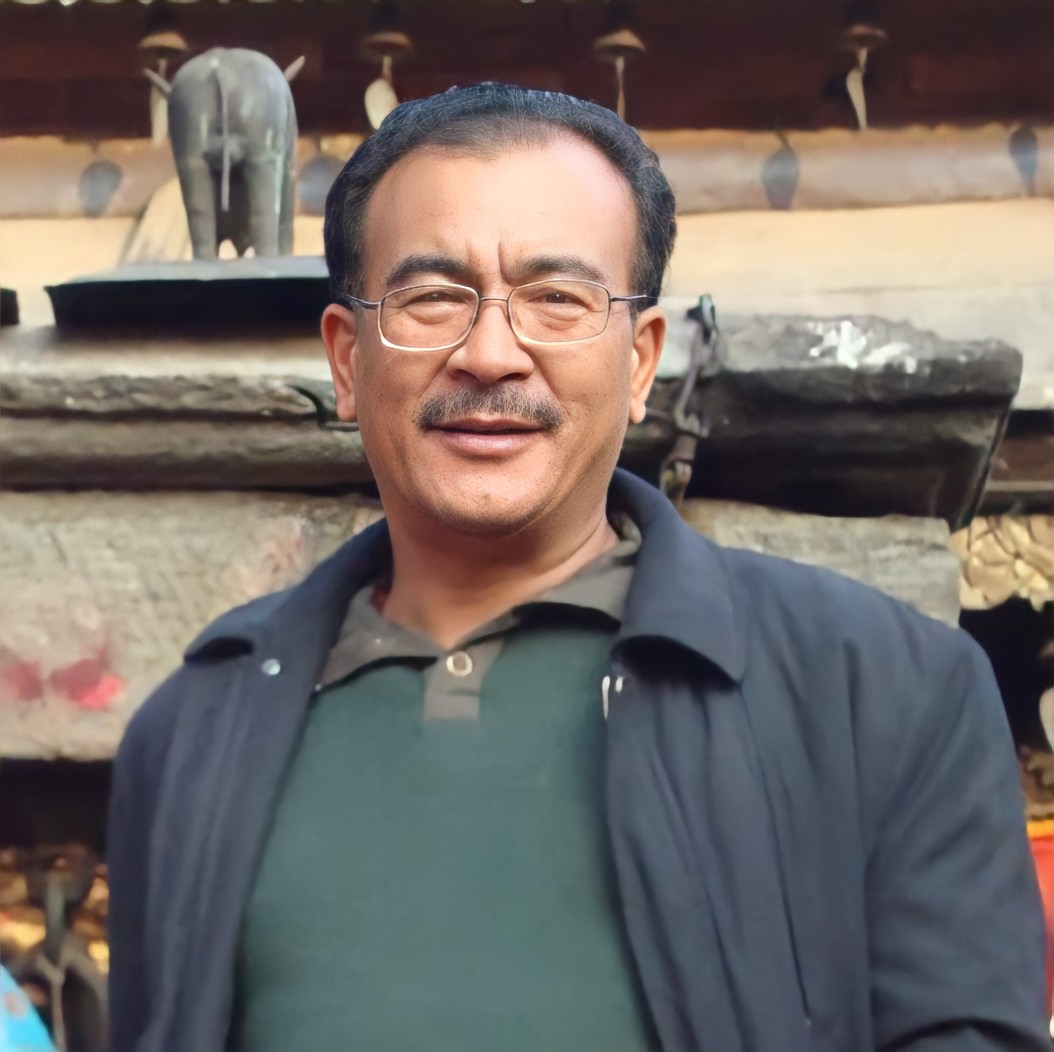

Durga Baral: First and still the best in business

Quick facts

Born on 18 March 1943 in Kaski Went to Multipurpose National High School, Pokhara Graduated from Prithivi Narayan College, Pokhara Started making newspaper cartoons from 1965 Husband of Parbati Baral Father to Anup Baral, Anil Baral, Ajit Baral, and Ajita Baral

I was born in a rural village of Kaski district. My mother died when I was only three and after her passing, I was not getting enough care and attention in the large joint family. My maternal grandmother realized this and took me with her to Pokhara. I started going to school only after I had reached 12 years of age, and completed my SLC in 1962.

I loved to draw from an early age. Back then, I used to draw pictures of animals and Hindu deities on walls and stones with charcoal. As far as I can recall, none of my family members was into arts. I think I was inspired by the pictures in my course books.

In the intermediate level, I studied science with biology as my major. We had to draw pictures of human organs, plants and animals and I was very good at it. Everyone used to love my drawings. It was one of my teachers who suggested that I study fine arts. I had never thought of studying arts, let alone making a career in it. There were no artists in Pokhara back then and I didn’t know how you became one.

So my teacher suggested I go to Kathmandu and apply for a scholarship under the Colombo Plan. And so I did. I didn’t get it. I applied thrice more and was rejected each time. By my fourth try, I had crossed the program’s 25-year cutoff age.

Even though I didn’t get the scholarship, my time in Kathmandu was fruitful. I met legendary artists like Bal Krishna Sama, Amar Chitrakar and Lain Singh Bangdel, among others. I got to learn a lot from them and their works. At that time, I also met Ramesh Nath Pandey, who was then the editor-in-chief of a weekly called Naya Sandesh. He was aware of my interest in art and offered me the job of a cartoonist in his paper in 1965.

I had no idea about cartoons or their purpose. I was not interested in politics and didn’t read international papers back then. But I was in desperate need of money to survive in Kathmandu. That was the only reason why I accepted the offer. It was Pandey who guided me in my initial days. He used to give me a broad concept and I used to draw accordingly.

I started going through international papers to learn more about cartoons. RK Laxman, cartoonist for Times of India, was my favorite. You can say I had inadvertently and rather disinterestedly become a cartoonist. I had to take on the identity also because Pandey used to introduce me as a cartoonist to his friends.

There were a couple of artists who made cartoons and caricatures but not for newspapers. Chandra Man Singh Maskey had once made a cartoon for a political pamphlet to protest against the Ranas. Gobardhan Sharma had similarly made one for Sanyukta Prayas, the mouthpiece publication of the Sanyukta Prajatantra Party. But I was the first to draw for a mainstream newspaper.

That was during the peak of the Panchayat period when independent media was heavily censored. Newspapers were unable to publish regularly. Also, they were supposed to educate people and make them aware of the Panchayat, not act as gatekeepers. Everyone used to contribute their articles to the papers without any remuneration and I too made cartoons without charge. It was a difficult life.

I joined the Janak Education Materials Center Ltd in 1966 as an artist. My job was to draw pictures for books and design book covers. My office also sent me to Japan for a three-month graphic arts training. I was a first-class non-gazette officer at the center but due to the lack of academic qualification, I could not be promoted to a section officer. I had no chance of advancing my career there, and I resigned.

I returned to Pokhara in 1969 and started a photo studio. The business ended in a failure. I then established an art studio. This enterprise proved quite successful. I had forgotten about my cartoon-making days in Kathmandu and was living a rather content life in Pokhara when I was once again pulled back into it. Some of my friends were publishing a literary magazine and they wanted me to illustrate it. I agreed and made a few cartoons in addition to designing the magazine covers.

Somehow my friends in Kathmandu saw this magazine and asked me to contribute to their newspapers. Once again, I started making cartoons for newspapers in Kathmandu. I had a mentor in Kathmandu, but I was on my own in Pokhara. So I started researching cartoon practices and closely following politics. I also joined college and graduated.

In Pokhara, there was an institution, Sikshya Sastra Adhyan Kendra, to teach art to school-teachers. I was called there to teach for a semester even though I was not interested in teaching. The campus chief convinced me, saying it was a temporary arrangement until they found a new teacher. I ended up teaching there until 2000—for a full 27 years.

I was working for the Gorkhapatra daily in 1993 and a Nepali Congress government was in place. I had drawn a cartoon for the paper that the opposition communist party found offensive. The issue was raised in parliament and the then Minister for Communication had to clarify the incident. The event made me realize that it is impossible to work freely within governmental organizations.

My pen name Batsyayana came after 1985. Those days, I was afraid of the political cadres and monarch’s supporters who could find my cartoons offensive and attack me. While searching for a pen name, one of my colleagues suggested Batsyayana. I didn’t like the name at first; I thought that it had an erotic connotation. But I eventually adopted it after learning that it is the name of a sage who was a master of many arts. Since then, the rest, for good or bad, is history.

About him

Tirtha Shrestha (Colleague)

Despite being an artist, he had a great passion for literature. He hence helped his litterateur friends by drawing their self-portraits for their books. People know him as a photographer, painter, and cartoonist, but he has also helped stage actors with their make-up and stage decoration. Durga dai is also someone who in 1990 anonymously helped usher in democracy.

Saru Bhakta (Friend)

Durga Baral’s personality was akin to a Bollywood hero’s: tip-top and dashing in his youth. We used to copy his style and looks. We worked together for many organizations and I have always found him genial and smiling. He has created a future for Nepali cartoonists. I have seen him devote a full day even to a small cartoon as if he was engaged in fine art. That shows his dedication.

Anup Baral (Son)

He is a perfect artist. He used to constantly redraw a single canvas until it satisfied him. All of his pieces have a social message. And as a father, he loves us of course. But he doesn’t know how to express it. The best thing about being one of his children is the freedom my siblings and I had growing up. We were never told to do this or that and were free to pursue our own interests.

A shorter version of this profile was published in the print edition of The Annapurna Express on August 11.

The stove comes to our rescue

It was almost nine at the wooded campsite on the Mahesh Narayan hill, and we were as yet unpacked. The 20-minute shoving of my bike up the darkened steep hill had burned me out flat.

An old hand at bike-packing, Shishir, swung into action and started pitching the tent. I began rummaging through our backpacks for foodstuff. We both had our designated jobs: Shishir would set the tent (I’d lend a hand), collect wood for the fire, and fetch water from a close-by natural spring. I was to cook.

The supper included a mix of rice and dal Shishir’s mom had packed for him. For the curry, we had the garden-fresh spinach we had collected from the charming Tamang ladies on the way and cabbage we bought at Bhanjyang Pokhari.

I was all set, but the fire was not. The twigs and wood we collected were too soggy. Shishir looked wretched, unable to light the fire. It was late, and both of us were starving.

Hang on! To my surprise, Shishir fished a portable stove out of his backpack. He figured it worked well for boiling water for tea or coffee—not for cooking rice and curry. We had to gamble, though, as the firewood proved a disaster. The gas burner lighted like a beauty, and I set upon it the degchi (saucepan) with the rice-and-dal-mix (khichadi).

I then tried my hand at lighting the fire as the rice pot sat on the burner—to no avail. We had little choice but to wait for the rice. Shishir kept eyeing the stove with distrust. It seemed to work just fine, however. And all this time, we got hungrier.

I had the cabbage and spinach chopped and ready, but the burner was not. The rice was taking longer on the shallow flame. “Shishir, if you had not thought of the burner, we would have had to munch on raw rice and dal,” I said, trying to ease the sticky situation. He just smiled back.

The night appeared leaden, with no sign of a single star. I wished it would not rain. Soon, fog swept the hill we were on, and the tall pine trees stood like silent apparitions in a ghost movie. I walked further into the woods with my headlamp on—just curious.

The hush of the night seemed soothing; only the sounds of the night bugs, katydids, or bush crickets broke the silence. I expected an owl to hoot, announcing strangers. Funny, there was none.

As I watched the night sky, still trying to locate some stars through the pine tops, Shishir said the rice looked done. I hastened to put another pot for the curry, fearing the stove might conk out (it did not). I sautéed the cabbage-spinach mix and let it simmer with the lid.

And after some 20 minutes, it was done, too. We wasted no time and began eating like pigs. I did not know how the food would taste. Shishir went for a third helping, and I did a second. So, it seemed the master chef of the night, I, came off with flying colors (ha-ha!).

As I prepared to sleep, Shishir announced he would fetch water for the morning. It was almost midnight, and I did not want him to go alone (or I left alone?). I volunteered. Off we went, squelching down a dark narrow trail with slippery moss-crusted stones.

The track appeared water-logged because of the rain. The thick wood and brush in the dead of night with no moon gave me the creeps. He said it was close, but it seemed like miles away. Anyways, we were soon back in one piece.

It was a little past midnight when we ducked into our two-person tent. The night was clement and peaceful, save for the sound of the playful night bugs and the soothing, whispering melody of the light breeze coursing through the soaring conifers—the smell sharp, sweet, and refreshing.

“Wow, your stove today proved a savior, Shishir,” I said. He just smiled back. Bleary-eyed, we finally ducked into our tent.

[email protected]