Kathmandu’s parking problems: Bad to worse

Nepal Police data show there were 191 deaths from road traffic accidents in the past fiscal: 85 of these casualties were pedestrians. Randomly and wrongly parked vehicles, on the footpath and the streetside, compel people to walk on the road where they are often hit by speeding vehicles, says Rajendra Prasad Bhatta, spokesperson of the Metropolitan Traffic Police Department. These deaths could be averted if there were a proper parking system in the city.

“You can’t park on the road. This is true for inner roads as well. But, in Kathmandu, every road is littered with parked bikes and cars. It’s a safety hazard besides a leading cause of traffic jams,” says Bhatta. The MTPD is trying to control this by fining such vehicle owners but Bhatta says they is only so much they can do with limited manpower and resources. He laments that people seem to obey the rules only when the police are patrolling the streets. Else, it is chaos, he says.

This comes from a lack of conscience as well as blatant disregard of the rules. People think they can get away with anything, with a little bit of aggression and connection. Then there’s also the fact that parking in Kathmandu is a huge problem. Available parking spaces are usually full, far away from your destination, or expensive (most parking lots charge above Rs 80 an hour for four-wheelers). But that still doesn’t mean you get to park on the road, Bhatta adds, even if it’s “just for five minutes” as most people claim when the police book them for the offense.

Suman Meher Shrestha, urban planner, applauds mayor Balen Shah’s efforts to demolish illegal structures in Kathmandu. This, Shrestha believes, will ease Kathmandu’s parking problems by at least 30 to 40 percent as both private and government buildings have been using parking spaces for other purposes. The mayor’s actions, Shrestha says, will also reinstate the rule of law in Kathmandu. “It’s total anarchy right now because there is no monitoring and enforcement of laws. Shah is definitely going to change that and restore order,” he adds.

The building bylaws have various provisions to facilitate parking in the city. Every commercial building must have its own parking area. The government has given incentives like tax deductions to systemize parking. But most building owners are taking advantage of weak monitoring to maximize profits by renting out parking lots or constructing stores or ATM lounges in the space. The local authorities could fix this problem and that is one of the many things mayor Shah is trying to do at the moment.

Talking to ApEx, many Kathmandu residents complained of haphazard parking. Recounting incidents of parked cars obstructing traffic in inner roads, to handle-locked motorbikes in front of main gates, people were clearly frustrated with the lack of a system. A local of Sanepa recalled an incident where an ambulance couldn’t reach its destination as a car was parked in the one-lane street leading to the house. They had to carry the unconscious patient till the main road. Spokesperson Bhatta says people must be proactive and call the police and report such wrongdoings. This will, in the long run, make them conscious of their actions.

Ganesh Karmacharya, project head, Department of Urban Development and Building Construction, on the other hand, says Kathmandu isn’t a planned city and that is the root of all our urban problems like narrow roads, lack of open spaces, congestion, etc. There is no option to constructing multistory parking lots in Kathmandu. We must use vertical space to mitigate parking problems in the city, he says. It’s not only the government’s responsibility either. Karmacharya says the private sector can and must be engaged in this.

“The government can direct the private sector to make use of this opportunity in a way that benefits them as well as the state,” he says. However, parking problems can’t be solved by focusing on parking solutions alone, say the experts ApEx spoke to. Our public transport system is in a complete mess. This has forced people to invest in their own bikes or cars the moment they have saved enough or are able to take a loan for it. Shrestha says if Kathmandu had an effective and reliable public transport system, people wouldn’t need to rely on private vehicles.

Arjun Koirala, senior urban planner, says other major cities in Nepal will also face problems that Kathmandu is going through right now if proper plans aren’t crafted and executed immediately. Core city areas are already congested and, with vehicle imports increasing every year, things will only get worse. “If we turn open areas into parking lots, we run the risk of losing essential breathing spaces. It’s a challenge to create more parking lots without ruining the city’s aesthetics and compromising on the greenery,” says Koirala.

The current situation is the result of poor planning and lack of foresight. Karmacharya says the government needs to take urgent action—maybe start by monitoring whether building bylaws are being properly followed. Then, it has to have elaborate discussions, at all levels, on how to manage parking in the city and come up with some concrete plans. “Our economy is also suffering because of the lack of parking spaces. People hesitate to go to many places in the city—like New Road, Bagbazaar, and Putalisadak, to name a few—as they don’t know where to park,” adds Koirala.

Limiting vehicular access to certain roads during certain hours could also help clear the roads. However, Koirala says this can affect people who reside in those areas so it’s best to weigh in the pros and cons before executing such plans. Another option would be using available, empty private plots as temporary parking spaces by collaborating with the owners. The KMC in its current demolition drive is taking stock of what parking places are already available.

These are, however, only a few possible options for immediate management of an escalating problem. For a sustainable and effective long-term solution, experts are of the unanimous view that the focus must be on changing our mode of transport. Koirala argues that as the city grows, vehicles will only increase. That will put more demand on the roads unless the government can provide mass transport. Shrestha adds that parking and congestion issues can’t be solved unless there is a solid public transport network in Kathmandu and people no longer have to rely on private vehicles as their primary commute option.

Ganesh Karmacharya, project head, Department of Urban Development and Building Construction, on the other hand, says Kathmandu isn’t a planned city and that is the root of all our urban problems like narrow roads, lack of open spaces, congestion, etc. There is no option to constructing multistory parking lots in Kathmandu. We must use vertical space to mitigate parking problems in the city, he says. It’s not only the government’s responsibility either. Karmacharya says the private sector can and must be engaged in this.

“The government can direct the private sector to make use of this opportunity in a way that benefits them as well as the state,” he says. However, parking problems can’t be solved by focusing on parking solutions alone, say the experts ApEx spoke to. Our public transport system is in a complete mess. This has forced people to invest in their own bikes or cars the moment they have saved enough or are able to take a loan for it. Shrestha says if Kathmandu had an effective and reliable public transport system, people wouldn’t need to rely on private vehicles.

Arjun Koirala, senior urban planner, says other major cities in Nepal will also face problems that Kathmandu is going through right now if proper plans aren’t crafted and executed immediately. Core city areas are already congested and, with vehicle imports increasing every year, things will only get worse. “If we turn open areas into parking lots, we run the risk of losing essential breathing spaces. It’s a challenge to create more parking lots without ruining the city’s aesthetics and compromising on the greenery,” says Koirala.

The current situation is the result of poor planning and lack of foresight. Karmacharya says the government needs to take urgent action—maybe start by monitoring whether building bylaws are being properly followed. Then, it has to have elaborate discussions, at all levels, on how to manage parking in the city and come up with some concrete plans. “Our economy is also suffering because of the lack of parking spaces. People hesitate to go to many places in the city—like New Road, Bagbazaar, and Putalisadak, to name a few—as they don’t know where to park,” adds Koirala.

Limiting vehicular access to certain roads during certain hours could also help clear the roads. However, Koirala says this can affect people who reside in those areas so it’s best to weigh in the pros and cons before executing such plans. Another option would be using available, empty private plots as temporary parking spaces by collaborating with the owners. The KMC in its current demolition drive is taking stock of what parking places are already available.

These are, however, only a few possible options for immediate management of an escalating problem. For a sustainable and effective long-term solution, experts are of the unanimous view that the focus must be on changing our mode of transport. Koirala argues that as the city grows, vehicles will only increase. That will put more demand on the roads unless the government can provide mass transport. Shrestha adds that parking and congestion issues can’t be solved unless there is a solid public transport network in Kathmandu and people no longer have to rely on private vehicles as their primary commute option.

Food habits: The one thing you can and must fix

Our environment has never been so toxic. There are many things working against us. Dr Keyoor Gautam, chairman of Samyak Diagnostic Pvt. Ltd., a pathology lab, says over 80 percent of those with fever are testing positive for dengue these days. Covid-19 is still a threat. Then there’s the trash dumped on the roadsides, giving off a foul stench and polluting the air, adds Dr Binjwala Shrestha, assistant professor at the department of community medicine at the Institute of Medicine, Tribhuvan University. Prevention aside—like wearing full-sleeved clothes to protect against pesky mosquitoes and masking up to stop the spread of Covid-19 and to save ourselves from the harmful effects of air pollution—we must also keep our immune system in top shape. One of the easiest ways to do that is by tweaking our food habits and eating right. “We can’t control external factors. But our diet is one thing we can fix. Our food choices also need to change with the seasons so that our bodies can adapt to the environment,” says Aarem Karkee, a dietician at Patan Hospital. The most basic thing we can do is eat at home and limit junk food and takeaways. In this hot weather, says Karkee, chances of dehydration, vitamin and mineral deficiencies, food poisoning and stomach flu are high. Eating at home drastically reduces that risk as we can control what goes into our food as well as ensure maximum hygiene. Then, we must also eat foods that are in season (for example, cauliflower, broccoli, cabbage, zucchini, bell pepper, and cucumber in summers) as these contain the highest amounts of water and nutrients. Our diet mostly consists of dal-bhat-tarkari. It’s generally what we eat throughout the year. The meal is laden with garam masala, ginger and garlic, all of which are heat-generating and thus not ideal for hot summer months. Anushree Acharya, dietician at Venus Hospital, Mid-Baneshwor, Kathmandu, says Kathmandu was once a lot cooler than it is today. Our staple diet was then ideal throughout the year. Not so now. She recommends cutting down on spices especially if you have digestive and sleep issues. “Have cooling foods like salads and other leafy vegetables. Include fruits like watermelon, papaya and pineapple in your diet. Curd is another great option to cool your body in this heat,” she says. It’s also not necessary to drink copious amounts of water. Bhupal Baniya, nutritionist at Nepal Police Hospital, says you must ideally consume 30 to 40ml times your body weight of water every day, which is roughly eight to 10 glasses. Many people tend to go overboard with their water intake, which is actually counterproductive. Overhydration can lead to as many problems as underhydration or dehydration—from electrolyte imbalance contributing to weakness and nausea to loss of water-soluble vitamins. Karkee says checking the color of your urine will give you a good idea of how much water you need. If it’s dark yellow or stains the toilet bowl, you need to drink more water. Whereas, if it’s transparent, almost like water, you need to cut down. In many parts of India, people mix sattu (roasted gram flour) with water, ice, black salt and lemon to make an extremely rehydrating drink to replenish lost electrolytes. Mint-infused or lemon water, Glucose-D, and even ORS can also be consumed on a daily basis to give your body that essential supply of electrolytes, says Acharya. Experts agree that people need to be conscious of what they are eating as that can have a profound impact on how they feel. This is especially important as your mind and gut are connected, determining your overall wellbeing. As the temperature continues to fluctuate, making the environment an ideal breeding ground for mosquitoes and all sorts of viruses, it’s become all the more important to give your body the internal boost it needs. And that can only come in the form of good, nutritious, season-specific food. Karkee’s advice is to consume whole foods in place of the polished, refined grains. Instead of white rice, he suggests brown rice or grains with the husk still intact. Replace your regular packaged dal with unpolished versions of the same from the local bulk store. Adequate consumption of fruits and vegetables can help regulate your body temperature and digestion, two crucial aspects for the system’s proper functioning. There is also no need to be hyper conscious of your salt intake unless you suffer from conditions that require you to monitor it. Our diet, he says, is deficient in iodine. Iodine deficiency can lead to growth and development issues in children as well as pregnancy-related problems in adults. The salt we consume is fortified with iodine and should be considered a dietary requirement. “There is actually no need to swap your regular salt with pink salt and such. In fact, I suggest you don’t,” he says. The crux of ‘beating the heat’ and being your fittest, healthiest self lies in what’s happening in your kitchen. Keeping a food journal—where you jot down everything you eat and drink—can help you get a sense of what you are doing wrong and fix it. Even better, take a photo of everything you eat and review it at the end of the day or week. Dr Shrestha says the key to eating right is understanding your food habits. That way you will be better attuned to the signals your body gives out when something isn’t working for you.

Branded goods: Loot in the name of luxury

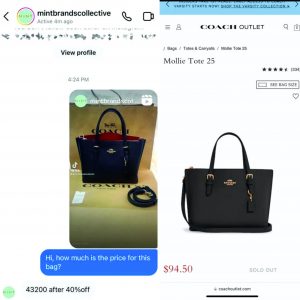

A Michael Kors handbag (Lita Small Leather Crossbody) costs Rs 39,000 after 40 percent discount at Mint Brand Collective, a women’s clothing store in Chhaya Center, a shopping mall in Thamel, Kathmandu. This particular bag is on sale on the international luxury brand’s website for $99 (Rs 12,567 at August 16 exchange rate). I paid Rs 14,500 for it when I ordered it online six months ago and it went through customs. A Coach bag, at the same store, costs Rs 43,200. This, again, is after their ‘40% Rakhshyabandhan offer’. The actual price of the bag, on the brand’s website, is $94.50.

When I questioned them about this discrepancy, Mint Brand Collective, on Instagram, claimed the original price of the Michael Kors bag was over $400. Add import duty and VAT and the price was reasonable, they argued. They deleted the message a minute after sending it—and then blocked me on Instagram. The next day, they posted a photo of the same bag on sale for Rs 29,900 on their Facebook page. I got a friend to sleuth around. She inquired about a few more bags. We discovered most bags cost more than triple their actual price. The 40 percent discount was just a ruse to fool people.

Jyoti Baniya, consumer rights activist, says there are many such unethical businesses in operation. The general rule is your profit margin cannot be more than 20 percent of the total price you paid at the customs department. For instance, if you have paid Rs 1,000 for a particular item, the maximum price you can sell it at is Rs 1,200. If someone charges more, they can be jailed for three months to a year and/or fined up to Rs 300,000.

“The reason that doesn’t happen often is because people let it slide. Nobody complains. If they do, the accused will be investigated and action taken,” says Baniya. People must report arbitrary market pricing, should they come across it. That, he says, is the only way to regulate and control the market. Businesses like Mint Brand Collective get away with duping customers because of loose monitoring as well as lack of information.

A few Nepali celebrities promote Mint Brand Collective as a one-stop solution for branded items like Zara, H&M, Coach, Michael Kors and Kate Spade, to name a few. Baniya says this kind of marketing creates a sense of trust among the public. They think if it’s endorsed by their favorite model, singer, or actor, then the place or service must be good. “If a business is cheating its customers, celebrities should have the moral compass not to promote it. It’s their responsibility as influencers,” says Baniya.

[caption id="attachment_29127" align="alignnone" width="300"] Mint Brand Collective asked for Rs 43,200 for this Coach handbag (left). The price of the

Mint Brand Collective asked for Rs 43,200 for this Coach handbag (left). The price of the

bag, as listed on the brand’s website, is $94.50 (Rs 11,995 at August 16 exchange rate).[/caption]

The Consumer Protection Act 2018 ensures the constitutional right of every citizen to quality goods and services. They can file a lawsuit when that right is violated and be compensated for it. The act also has provisions for fines and punishments. People ApEx spoke to were aware of consumer rights. What most didn’t know was that they could lodge a complaint at the Forum of Protection of Consumer Rights Nepal, or report the offense at Hello Sarkar. Many also didn’t want to ‘go through the hassle’, choosing to warn their family and friends of a ‘bad business’ and leave it at that.

Kumari Kharel, advocate, says most consumer rights complaints are related to expired food or medical issues. There aren’t many reports of exorbitantly priced luxury items. She believes this is why new businesses selling imported brands are cropping up every day. It’s their way of making easy money and they think they can get away with it. “But when customers start reporting these cases, the concerned government body will look into it. As it is, this issue has already caught the authorities’ attention,” says the advocate.

Social media platforms like Facebook, Instagram, and TikTok have also made it convenient for anyone and everyone to run a business. While that has its pros like low overhead cost and a chance to hone your entrepreneurial skills, there are plenty of downsides too—and it’s usually the customer who pays the price. These businesses slip under the legal radar. It’s difficult to monitor them as there is no record of their existence. They also don’t provide a VAT bill and often you can’t return or exchange an item.

According to advocate Kharel, there are laws to punish violators of consumer rights. There just needs to be stricter implementation of those laws. He cites examples of past raids at Bentley, a leather goods store at Durbarmarg, Kathmandu and other similar shops in the area, when customers complained of high prices—some stores had profit margins of as high as 2,300 percent. Kharel says investigators should be sent to different places in the valley for routine checks. If someone cannot provide the procurement invoice for their goods, they should be further investigated.

The Consumer Protection Act 2018 requires the government to establish a consumer court. In February this year, the Supreme Court ordered the government to establish such courts in each of the seven provinces. But there’s still no indication of it being done anytime soon. Activist Baniya says the media can play a crucial role in lobbying for a fast-track system where customers’ grievances are addressed. This, he adds, can instill a sense of fear and thus discipline and ethics in business operators.

Uma Shankar Prasad, an economist and a member of the National Planning Commission (NPC), says selling luxury goods at inflated prices is a market malpractice that the state must look into immediately. As Nepal has banned the import of luxury items and the country is also facing a dollar crunch, we simply can’t afford to let such black markets run rampant.

Rameshwor Khanal, another economist, on the other hand, sees this as a by-product of Nepal not being able to bring international brands or provide good local alternatives. The demand for brands has gone up and businesses are exploiting that, he says.

Many businesses importing branded items evade taxes while bringing and selling luxury goods. The items are usually brought into the country on baggage allowance or through other dubious channels that don’t go through the customs. “This will ultimately take its toll on the state coffers and increase the bigger gap between the haves and the have-nots,” says Prasad.

But all hope is not lost. The issue is being discussed at the NPC as well as the federal cabinet. “Hopefully we can come up with provisions to curb this market malpractice,” he says. In the meanwhile, Baniya urges people to report businesses like Mint Brand Collective so that action can be taken against them. “This will ultimately help regulate the market, make businesses answerable and ethical, and ensure you are getting your money’s worth,” he says.

Composting our way out of chaos

Solid waste management in Kathmandu sucks. There’s no waste segregation and recycling. Everything gets sent to the landfill. Landslides or protests by the locals frequently cut off the city’s access to Sisdol landfill site and now Banchare Danda, 1.9 km west of Sisdol, in Nuwakot. Bulging blue, black, and white polythene bags of trash then line our riverbeds and roadsides. In the first week of August, I counted 21 huge piles of garbage in a 500-meter stretch of road from Gaushala to Old Baneshwor. The rest of the city too was, more or less, in the same state.

Sanu Maiya Maharjan, a solid waste management expert, says composting is the only solution. She has been composting organic waste at home for over three decades, and says it’s fairly easy once you get the hang of it. But most people don’t want to put in the effort to learn to manage their waste. They want someone else to take care of it. “We must think of the laborers who handle our trash. Their work is especially difficult in the monsoon season,” she says. Not only do they get injured by needles and broken glass, they also face grave health issues. Often, they can’t afford medical treatment. As daily wage earners, their families suffer when they can’t work.

“Our trash is creating problems for other people. We have to be mindful of that and be conscious of how we throw what we throw,” says Maharjan who has, for a long time, strived to create a sustainable lifestyle. She practices vermicomposting (using earthworms to convert biodegradable waste into organic manure), does rooftop vegetable gardening, and has installed a simple rainwater harvesting system at home. She wants her actions to have minimal impact on the environment.

Apart from being a humane thing to do, composting could help you eat healthier and earn a little money as well. Maharjan uses the compost she makes in her vegetable garden, making her produce purely organic. She also routinely sells all the excess fertilizer she makes. “If you really want to compost, you can do it. Lack of time and space are just excuses for your unwillingness and indifference,” she says.

Dhurba Acharya of Solid Waste Management Association of Nepal (SWMAN) says composting must be done at three levels: household, community, and central. Those who can and want to should compost at home but the local authorities must step in where that’s not possible. Kathmandu is congested. Many families rent small spaces. You find up to 30 families are living in a building, says Acharya. Composting, in such cases, becomes tricky because of space constraints.

Laxmi Prasad Ghimire of Nepsemyak, a company that has been working in waste management for over 20 years, says the concept of ‘jutho’ also makes communal composting difficult. Many, he says, are disgusted by the idea of mixing other people’s kitchen waste with their own.

“Household composting can minimize our solid waste problem. It’s not the complete solution though,” says Acharya. For that, the community and the government must make provisions for large-scale composting. But private companies don’t have the land required to compost organic waste. (There is an unused plot of land near Banchare Danda that they are considering.)

Acharya says if people saw how composting could reduce trash volume at the landfill, they would be motivated to segregate as well. This would help increase the lifespan of the landfill as only 10-15 percent of the 1,200 tons of waste currently being generated daily would need to be dumped. Also, since dry waste won’t rot and stink, locals near the landfills wouldn’t object either.

Kiran Shrestha of Action Waste Pvt. Ltd says composting is a skill that needs to be learned and honed. It can greatly reduce the trash volume in Kathmandu. But Shrestha isn’t hopeful many people will do it. Since the local government announced separate collections of dry and wet waste, Shrestha and his colleagues have been doing rounds of their collection areas, helping people segregate their trash. Despite weeks of information dissemination, many still mix dry and wet waste. “It’s not just unawareness but laziness too. People don’t want to do the bare minimum,” says Shrestha.

Acharya adds that there was a time when private companies came up with all sorts of initiatives to get people to compost kitchen waste at home. From giving them discounts on monthly garbage collection fees to providing technical support, SWMAN tried to get them interested in composting. But valley residents would rather pay a little extra if it meant they could just toss out their trash instead of having to tackle it themselves.

Household composting might not solve Kathmandu’s issues but it will prevent your home from smelling bad when garbage collection stops. (Locals at Banchare Danda have declared they will not allow Kathmandu’s waste to be dumped there from August 17.) If you want to compost but don’t know where to start, you can contact the Department of Environment. Maharjan says they will teach you how to compost. “You can visit or call. The department can even send someone to your home to show you how it’s done,” she says.

Kheti Farm, a digital agri-food platform that connects farmers and consumers, sells compost bins that you can set up on your balcony or even your kitchen-corner. Each bin has a capacity of 110 liters and comes with a pair of gloves, a trowel, and a solution to mix with waste. Shiwani Goyal, customer care representative at Kheti Farm, says many people have bought these bins in the past six months. Kheti Farm has also instructed them on how to turn their waste into manure. “It will take about two months for the waste to turn into compost. All you have to do is put kitchen waste in the bin and add to it a few capfuls of the solution once or twice a week,” says Goyal.

The compost bin, however, isn’t a dustbin. You can’t put cooked food, meat, paper and plastic in it. For good compost, your kitchen waste should have 40-60 percent moisture; monsoon vegetables have over 80 percent. Maharjan suggests air drying kitchen waste before putting it in the compost bin. Also, large leaves and slivers of vegetable peels should be cut up into small pieces before composting. “A person on an average generates 300 grams of waste in a day, out of which 65 percent is organic,” says Maharjan. If you compost that at home, you will have very little to throw out.

How patriarchy promotes violence against women

A 13-year-old girl is raped. The policeman who is filing the complaint tells her she has a reputation for being sexually active. A gang-rape victim is questioned if she enjoyed ‘having sex’ with any of her rapists. At a school in Chitwan, the administration refuses to open a box of complaints by students after a girl is sexually abused by one of their teachers. They are told not to spread rumors. In Morang, an angry mob kills a woman police constable. She is on her way to arrest a teacher named Manoj Poudel who is involved in three incidents of sexual abuse.

Our society has always granted immunity to men. When a woman suffers abuse, she is told to let it go, not to create a fuss, or is blamed for what she had to go through—she must have done something to get unwarranted attention; dressed inappropriately perhaps or gone out alone at night? This promotes violence and limits women’s access to justice, says Lily Thapa, women’s rights activist and member of the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC). Worse, women choose to suffer in silence rather than go through the ordeal of speaking up and being stigmatized.

“The country’s institutions are run on patriarchal ideologies and women, as a result, are oppressed. Our socialization process also promotes gender discrimination, which ultimately manifests in mental, physical or emotional abuse,” she says. Thapa adds that gender stereotypes like ‘the father is the head of the household’, and ‘the mother cooks food at home’ litter our school curriculum. The role of the man as the strong provider and the woman as the meek caretaker is imprinted on children’s minds early on. Gender dynamics shape how we think and behave and it’s difficult to unlearn this later on in life and accept that men and women are equal.

Manju Khatiwada, undersecretary at NHRC, says our system is designed in men’s favor. From having different sets of rules for sons and daughters to political protection for criminals, men enjoy many liberties. The society, Khatiwada says, is highly tolerant of men’s mistakes while making no allowances whatsoever for women’s occasional slip-ups. If a man, say, has an affair, people character-assassinate the woman he is seeing.

A friend recently confided in me that a reputed corporate house she works at in Lalitpur fired a woman when she was caught having an affair with a married man. The man still works at the same office. His wife publicly attacked the woman when she found out about the affair, calling her all sorts of names while saying nothing to her husband. She claimed the woman had ‘honey-trapped’ her husband. Similarly, multiple women have accused a renowned cardiologist in Kathmandu of sexual harassment but no action has ever been taken against him. Rather, the hospital he works at covers up the incidents, sometimes even making his subordinates take the blame.

“We have all these ideas about how women should speak, dress, and behave but none for men. Instead, all kinds of excuses are made for men’s bad behavior,” says Khatiwada. The society’s patriarchal values have given men the confidence that they can get away with disrespecting women and violating their rights. According to a report by the United Nations Population Fund, 48 percent of Nepali women have faced some form of violence at some point in their lives; 15 percent of these women have faced sexual violence. The actual proportion is believed to be higher as the stigma of being a victim and the ensuing social ostracization keep many women from reporting violence.

Kamal Phuyal, sociologist, says most women are socialized to think of abuse and violence as their fate. He adds that women have inherited and internalized the culture of silence from their mothers and grandmothers. Many still think abuse is a domestic issue and that talking about it will bring shame to the family. Our family, education, society, and legal system support a culture of women’s dominance. Children grow up seeing gender imbalance at home. Schools don’t focus on moral education. Our society controls women in the name of religion and tradition. The legal system, with its many loopholes and red tape, acts late, if at all.

Phuyal says people are generally governed by various codes of conduct—be it social, religious, or legal. But, in our society, he laments, people make their own arbitrary rules. There’s a lack of conscience and responsibility. In rural areas, people still fear any misconduct on their part will hurt their reputation or negatively impact their families. This fear of societal scorn is lacking in urban areas. That coupled with a weak implementation of laws instigates violence. “Violence escalates when people believe they can get away with anything,” says Phuyal.

Mistreatment of women usually begins at home, though it might not be blatantly obvious at times. Women have little or no say in family matters. The male members of the family keep tabs on their whereabouts and spendings. They are second-class citizens in their own homes. The emotional and mental abuse goes unnoticed and many women suffer from depression and other mental health issues, says Rumi Rajbhandari, founder of Astitwa, an organization that works for the rehabilitation of burn violence survivors. Sometimes, this escalates to physical violence.

“Our male-dominated society imposes strict gender norms that dictate how we behave and interact and that puts women at a disadvantage,” says Rajbhandari. Men, she adds, often have an inflated sense of self and when things don’t go their way, their egos get hurt. Burn violence and rapes are usually the result of men not being able to take a ‘no’ for an answer, she says.

Raunaq Singh Adhikari, advocate, says there are many laws to protect women and ensure their rights but they are largely limited to paper. Our justice system needs a fast-track mechanism for cases of violence. The Supreme Court, in 2014, called for it among other changes but it has yet to be implemented. “It’s high time we addressed the legal issues that victimize women,” he says.

Lochana Sharma, counseling psychologist, on the other hand, says women need moral support in addition to legal help. In most cases, women fear backlash from their families, relatives, and neighbors and hesitate to share their stories. “Women need to be supported at home for them to be able to take a stand when needed. But sadly, our patriarchal mindset pulls them down. They are told to be silent and to compromise, often at the cost of their mental wellbeing,” says Sharma.

For women to live a dignified life, Undersecretary Khatiwada adds, what we need is a zero-tolerance policy for violence and a change in our socialization process. Activist Thapa agrees. She says the change must start from our homes. We must groom our children to respect others despite gender, class, religion and other manmade differences. Sociologist Phuyal says our education system needs to be reformed to include gender studies in the school curriculum. That’s the only sustainable solution to curb gender disparity and violence, he says.

The allure of English among Nepali parents

In the 90s and early 2000s, it was compulsory to speak in English at St Mary’s. Our teachers constantly reminded us to, often pulling us out of assembly lines to tell us we must obey the rule. We were punished and sometimes even fined if we were found talking in Nepali. School captains would monitor us during the lunch breaks, reporting anyone who slipped up. We had to constantly force ourselves to talk in English; it didn’t come naturally. We would invariably switch to Nepali or add ‘ing’ to Nepali words when we didn’t know how to say something or wanted to be rebellious and hip.

Good English meant you were a good student. It was a determinant and an assurance of sorts of a successful life. So private education was largely focused on English and the burgeoning of English medium schools in the 90s further fostered this trend. Fast forward over two decades later, the situation is the same except children today don’t have to be coerced to speak in English. They do so because they want to. Many don’t at all speak in Nepali or other native languages like Newari. Ask them something in Nepali and they will invariably respond in English. Access to the internet—games, cartoons, and other videos—means children pick up English words early on.

Anita Portel Gajmer, a kindergarten teacher for 13 years, says Peppa Pig, a British animated series, is popular among children, and it shows in their pronunciation. Children these days, she says, are exposed to a lot of English content, but there aren’t many child-friendly Nepali or other local language videos online. They are, thus, already speaking in English by the time they go to school. Schools, in turn, encourage and applaud their tendency to speak in English. “Our education system is English-centric. All the subjects like math, science, history and geography are in English,” she says. There is also an innate bias for the language. Most parents, she confesses, are proud that their children speak in English and not their native tongue.

Nepalis’ fascination with English sweeps other languages to the sidelines. According to the 2022 census, 123 languages are spoken in the country. Quite a few parents confessed to speaking with their children exclusively in English. They feared not doing so would make their children’s English rusty or they would get confused with different sounds and words. Bhandra Sharma, senior journalist who writes for The New York Times, says he went to a government school and learnt English late in life. He faced a lot of challenges because of it. He doesn’t want his children to go through that. A sound knowledge of English, he says, is essential to compete internationally. His daughter, Bihanee, speaks both Nepali and English though she confesses she’s more comfortable in English.

But studies show that bilingual children have ‘cognitive flexibility’. When a bilingual child attempts to communicate, the languages in the brain compete to be activated and chosen, making the brain sharper. A 2004 study by psychologists Ellen Bialystok and Michelle Martin-Rhee found that bilingual children were better at dividing objects by shape and color. Monolingual subjects had trouble when the second characteristic (sorting by shape) was added. The study concluded that being bilingual was better for the brain’s command center. You were more likely to be mentally sharper if you spoke two or more languages.

Namthak Rongong, a nine-year-old boy who studies at a private school in Lalitpur, also prefers to speak in English. His Nepali isn’t very good, admits his mother, Kabita Rongong. “It was only during the Covid-19 lockdowns that he started speaking in Nepali as my husband and I speak in Nepali at home. He also picked up a few Newari words as I speak Newari too,” says Kabita. But Namthak still mostly answers in English even when someone speaks to him in Nepali. He also has an accent that he claims to have picked up from his friends at school. His mother, however, wants him to be fluent in English as well as other languages, be it Nepali, Newari, or Japanese. In fact, as the founders of Namthak’s school are Korean, some parents have actually put in a request for Korean classes for their children.

Children speaking exclusively in English also leads to communication problems in the family as the older generation might not be fluent in it, says psychologist Minakshi Rana. She has seen many families where the bonding between children and their grandparents has been affected by their mutual incomprehension. The communication barrier makes children aloof and unempathetic.

Rana says there are a few reasons Nepalis seem to prefer English to our own local languages. One, it stems from the parents’ inferiority complex: Their children must speak in English to appear proper and posh. Children, they believe, have better self-esteem when they can converse in English. “In many cases, it also has a lot to do with our inability or unwillingness to accept our diverse cultures. Western culture is considered superior and their language better,” says Rana.

Sanorip Rai, who has been working at Ekta Books in Jawalakhel, Lalitpur, attests to that. She says she regularly hears parents talk to their children in English despite not being fluent in it themselves. The government recently added social science in Nepal to the school curriculum. Parents frequently tell her how difficult it has been for their children who, at most, have a very basic understanding of Nepali. But there is a glint of pride underlying their complaints and that is worrisome, says Rai, whose 19-year-old son speaks fluent Nepali. She fears he could be the last generation of high-school graduates who can actually write and speak proper Nepali—or any of our other national dialects for that matter.

Portel says soon it will be difficult for even primary school teachers to understand what children are saying because of the different accents and that will hamper their learning. She adds education is mostly becoming about how good your English is. It’s creating a class divide—if your child speaks in English, it means s/he goes to a good (read: expensive) school. “It’s becoming a reflection of your social/financial status,” she says.

Learning and speaking English isn’t a bad thing. After all, it’s the universal language. But our approach to this has been all wrong, say the people ApEx spoke to. We are dismissive of local languages that are easily accessible to us and that restricts our cognitive development, communication skills, as well as acceptance of different heritages. By restricting ourselves to a single language, we are also putting up barriers—in our society and in our minds—instead of bringing them down. “Bad English is shameful but we practically boast that our children aren’t good at Nepali or Newari or any other local dialect. That this not only puts them at a disadvantage in learning and development but also gives them a false sense of self. And that can have disastrous consequences,” says Rana.

Why are Nepalis abandoning their pets?

Most of us have a pet or two at home. They are our friends, an extension of our families. We might forget to take them out sometimes and they may soil our carpets but we still love them, and they us. But when we bring in pets on a whim or consider them status symbols or guards, we blur the line between compassion and cruelty.

Recently, animal shelters have rescued many abandoned dogs from the streets. They are often in a bad state—dehydrated, unable to stand or walk, blind, suffering from different skin issues, etc. Some are beyond saving.

What generally happens, say activists, is people bring in a dog for a purpose—to placate their children, to scare away intruders, or to keep up with that neighbor who got an expensive purebred. The novelty wears off pretty quickly. “Puppies get bigger and aren’t ‘cute’ anymore, or people discover that the dog has needs, that it needs to be fed, groomed, and occasionally taken to the vet,” says Shristi Singh Shrestha, an animal rights activist. And what follows is utter inhumanity: They are left on the streets. People take them for a walk and leave them tied to a tree or a pole, or they are put in cars and dropped somewhere far off so that they can’t find their way back home.

“Pedigree dogs are all the rage. Everybody wants a fancy, good-looking dog. But they don’t understand what it means to have a pet at home,” says Shristi. Every dog has a personality and will grow and adapt to its surroundings differently. Besides having specific feeding and grooming needs, how a dog turns out largely depends on how it’s raised. Many dog owners keep their pets chained or caged. They beat the animals to ‘train or discipline’ them which in turn make them aggressive and lead to behavioral issues. Then, as seen in Kathmandu, their owners get rid of them.

Animal Nepal, a non-profit animal welfare organization, rescued seven pet dogs in the past month. This is not counting the dogs that have died on the streets or been abandoned in forests where they have been attacked by wild animals. Sushant Acharya, veterinary technician who is a part of the Mobile Rescue Team at Animal Nepal, says they had been rescuing at least a couple of pet dogs a month for a while now but the number has gone up recently. Earlier it was mostly German Shepherds on the streets but now they find Boxers, Pugs, Huskies and Labradors too.

Sneha Shrestha, founder of Sneha’s Care, a non-profit animal rescue organization, says when you bring a dog home, you must understand it’s a lifelong commitment. A dog isn’t a toy, she says, not something you can outgrow and toss out. Sneha’s Care gets many emails and messages requesting the shelter to ‘adopt’ their dogs as the family is migrating abroad or their dog bit someone and they are now scared of it. Despite Sneha’s team trying to convince people that they are responsible for their pets, most of these dogs invariably end up on the streets. “I believe, more than ever, that there’s no humanity. Everything is a matter of convenience, even an innocent being’s life,” says Sneha.

Ananda Dahal, chairman, Nepal Animal Welfare and Research Center, says abandoning pets when they become aggressive, ill or old is classic apathetic behavior. It is no surprise to him because humans always put themselves first. We consider ourselves superior and our lives more valuable. Everything else is disposable. Dahal says people routinely abuse street dogs and get away without even a warning. Instead, the police have declared that dogs are a nuisance, a threat to the community. “Our system fuels animal cruelty by devaluing other forms of life,” he says. Abandoning pets, he says, is perhaps the highest form of animal cruelty.

Pet dogs aren’t street-smart. They aren’t able to take care of themselves—they can’t scavenge for food and they don’t know what to do on the roads. They usually get run over by vehicles. The problem isn’t lack of awareness. The sad reality is people know what will happen to their abandoned pets but they don’t care. As there are no repercussions for their actions—their dogs cannot be traced back to them—it has become convenient to get rid of unwanted pets. This is why registration, some sort of taxation, and microchipping pets is important, says Shristi.

Leaving pets on the streets is an escalating problem but not a difficult one to solve, say activists. The key lies in making it tricky to bring a pet home. Right now, anybody can just walk into a pet shop and buy a dog they want. If pets had to be registered at the ward office, people would think twice and only those who are absolutely sure they want one would go through the hassle.

Microchipping would prevent pets from being lost and if someone were to abandon theirs, the dog could be traced back to the owner and punishment meted out. Currently, the Animal Welfare Law provides for up to three months’ jail-time for those found guilty of animal-cruelty. But there is no way of proving who an abandoned dog belongs to.

Raina Byanjankar, founder of Oxsa Nepal Animal Welfare Society, says keeping pets has become more about showing off than about their companionship. People see Golden Retrievers and Labradors in ads and social media, and celebrities carrying tiny dogs in their purses, and they want that. We saw dire wolves—Ghost, Summer and Nymeria among others—protecting the Stark family in the ‘Game of Thrones’ which aired for eight years. Ghost was an Arctic wolf while Summer and the others were a crossbreed of Siberian Huskies, Samoyeds, and other northern breeds. Following global trends, in Nepal too everyone now wanted a Siberian Husky aka their own dire wolf.

Though Siberian Huskies are known as hardy and adaptable dogs, they thrive in colder climates. Extreme heat can be discomfiting and lead to skin and other health problems. It’s the same with other breeds of dogs being reared for commercial purposes at various pet shops, clinics, and breeding centers. Meanwhile, Nepali dogs, which are some of the world’s oldest breeds, have strong immune systems and live for up to 20 years. These dogs are acclimatized to our climate as well.

“But they aren’t trendy enough for most Nepalis,” says Byanjankar. The result is an unethical breeding industry that practices and promotes animal cruelty. Recently, actor Priyanka Karki put up a bunch of Siberian Husky puppies for sale, drawing flak from animal lovers and activists who fear her action would endorse breeding. “It’s also necessary to control dog breeding in Nepal. We simply don’t need European or American breeds,” says Raina.

To create awareness about adopting local dogs and not buying pets, Animal Nepal in collaboration with The Jane Goodall Institute Nepal is celebrating July as the National Month of Dogs. Eventually, they hope to put this on the calendar. “It’s all about being compassionate towards animals. We must start at our homes by taking full responsibility for our pets. The best practice would be to adopt dogs from animal shelters instead of buying them from breeding centers,” says Shristi. “If you love dogs and want a pet, why does it have to be an expensive one?”

What perpetuates patriarchy in Nepal?

Keshav Sthapit, a two-time mayor of Kathmandu, recently told a woman that ‘she had a nice face but her mouth wasn’t proper’ when she questioned him about the #MeToo allegations against him. His audacity to do so and still maintain that he hadn’t crossed a line spoke volumes of our society’s attitude towards women—that there are special rules they need to follow and ways they have to act. Despite protests to revoke his mayoral candidacy, Sthapit went on to contest the local elections for the third time. This is just one of the many instances Nepali men have gotten away with grossly inappropriate behavior due to the special status they enjoy.

“Gender discrimination is still rampant around the world. Deep-rooted patriarchal values allow men to be disrespectful towards women and to think nothing of it,” says Lily Thapa, women’s rights activist and member of the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC). This week, in the United States, the Supreme Court overturned the 1973 Roe vs Wade ruling, taking away women’s constitutional right to abortion. American women, it seems, no longer have the right to reproduce or to enjoy their bodily autonomy. This setback came at a time the global feminist movement had only just been gaining traction.

Our society has always wanted to control its women, says Sujit Mainali, historian and author of ‘Sati: Itihas ra Mimamsa’ that details how the Hindu religion and culture as we have practiced them have largely determined women’s fate. The practice of Sati (the wife burning herself alive on her husband’s funeral pyre) was a form of extreme violence inflicted on women. It was a way to ensure a woman couldn’t be unfaithful to her husband even after his death. The man’s extended family could then lay claim to his property. Also, since a woman’s identity was wholly dependent on her husband’s, her life wasn’t considered worth living without him around. Unlike the stories we were told—of devoted wives flinging themselves in the fire—those women, Mainali argues, didn’t die willingly. They were often brainwashed, probed with sticks, and even drugged. A few of those who went of their own volition did so because they knew, without their husbands, the society would forever taunt and torture them.

Even though Nepal abolished Sati in July 1920, its trickle-down effect can be felt over a century later. Our culture is still used as an excuse to justify gender inequality, or women’s oppression more specifically. The ‘male privilege’ that we see today, Mainali says, stems from men wanting total control over women’s sexual life. Women being confined to homes and household activities is an extension of that sexual containment.

“There is a continuation of the same kind of rules that enforced the Sati system. Women aren’t burnt alive now but they continue to face discriminations and all kinds of abuses,” says Mainali. The biggest indicator of gender disparity is violence against women. In 2020-21, there were 1,393 reported cases of rape in Nepal. A UN Women study found that in combat zones it’s more dangerous to be a woman than to be a soldier.

Anjali Subedi, freelance journalist, says the problem lies in the way society looks at women—completely different to the way it views men. The society has a more liberal attitude towards men and their faults and infractions are often ignored or defended. Whereas women are expected to have all the ‘noble’ qualities like being silent, tolerant, patient and forgiving. Our definition of masculinity encompasses everything considered unbecoming of a woman—being loud, opinionated, strong, stubborn, et. al. “Women have to adhere to discriminatory societal rules. She is judged, shamed, and ostracized if she doesn’t,” says Subedi.

Santosh Pariyar, writer and social activist, says patriarchy dictates our political ideology and thus its impact is pervasive. Women aren’t included in decision- and policy-making, which is often a male-dominated space. That’s why feminist movements don’t have the desired results or bring sustainable changes. “Any change it does manage to bring soon fizzles out as our polity’s watchdogs aren’t interested in securing that change,” he says. A rigid dichotomy of gender roles is entrenched in our system. That makes it hard for both men and women to be something other than what they are traditionally supposed to be. Add to that a hegemonic system of power and women are overwhelmingly oppressed and exploited. “Right-wing politics is gaining ground everywhere in the world, painting a bleak picture of our collective future,” says Pariyar.

Historically, women’s domination and abuse that stems from it have been all about men’s need for control. Studies suggest that in most cases men’s use of violence is a tactic to control women and emphasize their power over them. Thapa of NHRC says women often have nowhere to go for immediate help when they are abused or raped because all our institutions are biased towards men. From families telling women to ‘let things go to maintain peace or marital relations’ to our authorities’ insensitivity, there’s a lot working against women. “This perpetuates a culture of silence and forces women to put up with abuse,” she says. “That is the most horrifying effect of patriarchy.” Patriarchy also limits women’s access to resources that can ensure their rights or help them fulfill their potential.

Violence is the ultimate manifestation of gender discrimination. But it rears its ugly head in many forms. Avasna Pandey, lecturer, Department of International Relations and Diplomacy, Tribhuvan University, says gender inequality is all too evident in everyday situations. At home, the woman is the primary caretaker. She has roles she needs to fit into. Any deviation and she becomes ‘loose and immoral’. In the workspace, women are often paid less than men for the same job or are given lower positions, if she is hired at all. A pregnant friend told me she didn’t tell her prospective employers that she was expecting. She feared she wouldn’t be hired as taking care of the baby would soon be her ‘primary’ responsibility.

“Take something as simple as being referred to as ‘sir’ in work emails. Our society expects only men to be in positions of power,” says Pandey, adding that gender disparity plays out in many small covert and overt ways. At the root of this inequality lies the acceptance of the supposed superiority of one gender and thus its power over the other. However, Thapa says despite all the regressive moves and daily struggle she is proud that women are continuing to come out with their stories and break the culture of silence. “That’s the only way forward if we hope to create an equal society. The unfolding global scenario can be disheartening but we can’t let anything deter us. We have to be stronger than ever,” she says.