Opinion | Angry country: A case for compassion

A boy called me a whore. He couldn’t have been older than 15. The reason: I brushed against the side-mirror of the scooter he was riding pillion on while crossing a road peppered with potholes, and the rider had to swerve a little. The teen, with a mask strapped below his chin, gesticulated wildly and even turned back to glare at me from some distance away.

The sad thing is these kinds of incidents are quite common. It doesn’t take much for people to lose their cool and start spewing obscenities. Consumed by an underlying rage, we have never been a tolerant lot. A banal, inconsequential thing can send us over the edge. Worse, those in power have always brandished their authority by raising their voices.

I remember a traffic police yelling at my dad in Durbarmarg, Kathmandu. We had just stopped to get some ice-cream and had parked the car by the road for five minutes. I was barely seven and thought the man would harm my dad—the way he kept repeating the same thing over and over—“Will you give me your license or should I puncture the tires?”—was menacing. I still think about that incident every time I see policemen argue with the public, which is all too often. They rarely ever speak properly, grunting and huffing unnecessarily. The public, in return, doesn’t relent easily either.

The outpouring of aggression seems to get worse by the day. Political discourses drip with sarcasm and rage. Social issues have extremists fighting nasty battles complete with name-calling and rape/death threats. The online debates (if you can call them that) and comments on the Rupa Sunar-Saraswati Pradhan controversy will make you want to scoop your eyeballs out and give them a vigorous scrub. Oh, the blasphemy.

Neuroscientist R Douglas Fields, in his book ‘Why We Snap’, says we are more prone to lose it when it’s a matter of life, family, honor, our freedom, territory, resources or social justice. Stressful situations, he writes, can initiate an automatic rage response. Thanks to our evolutionary past, he adds, under the right circumstances, anyone can lash out violently. The neural circuits that helped our ancestors protect themselves and survive recognize and respond to dangers in our current environment as well.

Anger, historically, might have been necessary for survival but today, I feel, it’s more an assertion of power and our inability to accept even an iota of responsibility in any wrong. Articles on anger management and how it affects our bodies claim people are busier and thus strapped for time which predisposes them to anger when things don’t go their way. But does anger serve a purpose? Or do we worsen our situations by reacting like lunatics? Are harsh words necessary to convey a message?

I, for one, stop listening when someone’s voice goes above a certain decibel. I’m sure that’s true for most of us. Tell me something in a controlled tone and I’m receptive to what you are saying. Say the same thing, in a higher pitch and throw in a few gestures, eye roll, headshake, and the like, and, in my head, I’ve made you out to be a dumb, illogical person and switched off my senses.

That doesn’t mean I don’t fight anger with anger. But over time, I’m learning to control my emotions because all arguing with an angry person does is get me riled up. It’s a disruptive force. As clichéd as it sounds, deep breaths help. As does picturing myself with a puffy red face and saucer-sized eyes. I have used that technique a gazillion times to calm down.

My father once said being angry is like having poison and hoping the other person will die. The line might have been copied from somewhere but he was also speaking from experience. These days, he prefers to keep quiet and listen rather than retaliate in anger and further upset himself. Let it go, seems to be his mantra. It’s a stark contrast to a man whose self-righteousness never let him back down from an argument.

Apparently, research backs his claims too (though it for sure wasn’t what was on his mind when he had his Buddha moment). Studies have shown that anger can cause physiological changes that affect blood pressure, heart rate and digestion. Chronic anger has even been linked to heart attacks and other cardiovascular problems.

The problem with us these days is we are rarely, if ever, trying to make a point. The focus is largely on proving the other person wrong or belittling them. Paul Bloom, in the book ‘Against Empathy’, says we feel empathy most for those who are similar to us and not at all for those who are different, distant, or anonymous. Perhaps it’s a lack of empathy that’s the source of all the anger that fuel conflicts these days. When the Covid-19 pandemic has made it obvious that life can be fickle, gone at the blink of an eye, aren’t we better off being a little more compassionate and a lot less angry?

The corrupting culture of ‘chiya kharcha’

Chiya is a culture in Nepal. So is chiya kharcha. That dreaded extra at government offices (much like service charge and VAT at restaurants) is what gets our work done and with minimal hassle. But every time our wallets are a bit lighter, we feel a little wronged.

Sociologist Chaitanya Mishra says these under-the-table dealings all of us are so accustomed to is basically abuse of power and position. Unfortunately, it has its roots in history—our grandparents and their parents did it—and thus its hold is still strong. What’s also true is that most of us like to speed things up (as government offices can be notoriously slow) or to not have to wait in long queues or shuttle from window to window, and don’t mind parting with a few thousand rupees (and often more) for it.

“People have money. What they don’t have is time and patience and the willingness to follow protocol when a shortcut is available,” says Mishra. So, we might crib about a system where chiya kharcha is all too pervasive but we are the ones who are, in fact, perpetuating it.

Of the 25 people ApEx spoke to, 21 said they had given chiya kharcha at various government offices in Kathmandu—wards, municipalities, land revenue offices, and the department of transport being the most common places. Thirteen of the 25 said they were asked for a certain amount while eight had offered money themselves in exchange for ‘help’.

Sanjib Shrestha, proprietor, Wicked Villa Resort, says he dislikes the idea of chiya kharcha. However, sometimes it’s inescapable. For instance, he had to finish some official work before the lockdown this year and he was told it would take at least a week, by when the lockdown would have come into effect. Rs 40,000 got the work done in an hour.

“Many government employees are just looting the public. But when the entire system is corrupt, you succumb,” he says.

People’s perception of corruption in Nepal is the worst among 17 Asian countries as surveyed by the global anti-corruption advocacy group, Transparency International. According to the Global Corruption Barometer-Asia, 58 percent of the respondents said corruption had increased the most in Nepal in the past year.

Chiya kharcha is a small part of a larger corrupt system where money and connection can facilitate even illegitimate matters. But it’s supposedly the most frustrating as it makes people feel helpless. It’s also testimony to the great divide between the have and the have-nots, a ‘those who can afford it will be given the service while those who can’t must suffer’ attitude of governance.

Worse, it seems quite evident that grease money is the basis of Nepali polity and corruption of our democracy. So, most people seem to have simply given up, accepting bribery as part of our culture—a necessary evil. Every project, big or small, has a chiya kharcha budget.

Auditor Khagendra Pokhrel says giving chiya kharcha at government offices—to those who are already drawing steady and perhaps hefty salaries (perks not included)—is an irresponsible and immoral thing to do on the public’s part. But when you stand to suffer because of someone else’s lack of integrity, it’s also the only way out.

Every government office has a citizen’s charter in its premises. It clearly states the role of that office and its staff as well as the time it’s going to take to complete the various tasks that particular department is assigned. Failing that, the public has the right to lodge a complaint.

However, the process is long. It further delays your work. And, more likely than not, the blame will ultimately be pinned on slow internet or some other technical glitch, says Pokhrel.

Sociologist Mishra says chiya kharcha is the result of a society that equates position with privilege. Government offices are thus places of service—not for the public but for the officials working there. The attitude is, if you want something, you have to be subservient. Pokhrel adds that holding your ground and not giving chiya kharcha creates a hostile environment.

However, Mishra says all is not lost. He reckons the tendency to ask for chiya kharcha in many government offices is on the decline. In most places it’s not as overt as it was before, he says, and that’s a hopeful start of an imminent change. What the public can do now, he adds, is try and ignore the covert hints.

Swarup Acharya, journalist, Kantipur Publications, believes the reason behind government officials’ hesitance to outrightly ask for chiya kharcha in recent times is the real possibility of sting operations and other similar exposes.

“Everybody and anybody could be carrying a hidden camera or recording the conversation on their phones these days. There are many YouTubers and bloggers doing just that and posting such content online,” says Acharya. That, he adds, has made them a lot more vigilant and less likely to ask for chiya kharcha or bribes which is essentially what it is.

Turns out chiya kharcha doesn’t necessarily always have to be in cash either. Grishma Ojha, project coordinator, Help Code Nepal, says there have been people who have asked for groceries and other such supplies in exchange for their services or favors. The fact remains Nepalis have to part with more than the stipulated amount for official works.

And there is nothing chiya kharcha won’t get done. From easy school admissions to same-day issuing of passports, everything has a price. Fourteen years ago, a recent college graduate failed his driving license trial. For Rs 13,000, he got a license a couple of days later. Another woman in Lalitpur got hers delivered at home for Rs 50,000 a few years ago. A woman who wasn’t born in Nepal has a birth certificate certifying she was. A 55-year-old got vaccinated against Covid-19 when Nepal was apparently only vaccinating people above 65. The Rs 2,500 she spent at the ward office for a recommendation was worth every paisa, she says.

Sociologist Mishra says chiya kharcha will be a part of our lives unless there is an efficient and accountable government. It’s not something individual action can change. As bleak as that might sound, the truth is we are all victims of a corrupt system. For every person who doesn’t give or take chiya kharcha, there are at least a dozen who will.

“What we can and should do is talk about it. Let’s not remain silent and accept it as a part of life,” concludes Mishra.

Nepal Floods: Same story, different year

Monsoon is a hot topic right now. And rightly so. It has just started and already there has been a steady stream of gut-wrenching news of floods and landslides. The problem, however, is that monsoon is only an issue during monsoon. Once the rain abates, we forget about the devastation it left in its wake. We will, for sure, talk about it again. But until next monsoon, there will be other issues to occupy us.

It’s this attitude of the country towards water-induced disasters that leads to a déjà vu like situation in Nepal year after year. Our approach to disaster management is rescue and relief operations-centric rather than focused on preventive measures. Dil Kumar Tamang, operation chief, National Emergency Operation Center, Ministry of Home Affairs, doesn’t deny this. He says minimizing disasters and the potential losses—of both infrastructure and lives—should get as much importance, if not more.

“We are trying to work out ways in which we can prevent and mitigate disasters,” says Tamang. However, there is, he adds, a need to learn from past mistakes and revise plans accordingly as well as emulate international practices of disaster prevention. The main focus should be on developing reliable early warning systems that will give people enough time to get to higher ground.

Geologist Prof. Dr. Bishal Nath Upreti emphasizes the need to install weather forecasting and radar stations throughout the country to make real time data collection and analysis possible. Only accurate weather prediction can help mitigate the effect of natural calamities in a disaster-prone country like Nepal, he says. And, we have, thus far, failed to prioritize it.

He says when Nepal first started giving weather forecasts on television and radio, a running joke was that the forecaster would look out of the window at the time he was scheduled to go on air to check whether it was sunny or cloudy. Dr Upreti laments that our weather forecasting system today isn’t a whole lot more advanced than that. The Department of Hydrology and Meteorology (DHM) under the Ministry of Energy, Water Resources and Irrigation was until quite recently the most neglected department of all, reeling under manpower and budget constraints.

Currently, the DHM is doing whatever is in its capacity, says Tamang, but various concerned departments, the local government as well as people should work together to change the way disasters are handled in Nepal. The effect of collaborative effort can be far greater and impactful than individual action.

Full story here: Floods in Nepal: A recurring nightmare

Floods in Nepal: A recurring nightmare

During monsoon, intense incessant rain wipes out entire villages and settlements in different parts of Nepal. Hundreds go missing and many lose their lives. Local authorities and various organizations spring into action, rescuing people and offering food supplies and medicines. For months, floods and landslides are everyone’s concern. The rain stops. The issue wanes. The vicious cycle repeats itself year after year.

This year, as per reports, at least 18 people, including four women and three children, have been killed due to landslides and floods triggered by heavy rain across the country as of this writing. Another 21 have gone missing. The Tatopani border point in Sindhupalchowk has been closed after floods from the Bhotekoshi river damaged roads leading to it. A dam in Kachanpur has been washed away by a flooded Mahakali river. And it’s only just the beginning of monsoon.

Nepal, due to its geography, is a disaster-prone country. Add to that rampant deforestation, river-bank encroachment and climate change, which have collectively led to recurrent floods and landslides over the years. The repercussions are made worse by a negligent system that has never prioritized water-induced disaster prevention. Experts believe drastic steps should be taken immediately.

Prof. Bishal Nath Upreti, geologist and president, Nepal Center for Disaster Management, believes the government needs to take some concrete steps to lessen the threat of regular floods and landslides. Unfortunately, he says, it has been all talk and no action on disaster preparedness.

The first and foremost way to tackle water-induced disasters, he explains, is through accurate weather forecasting. Weather radar is vital to monitor the atmosphere and provide weather forecasts and issue warnings to the public. Nepal has one radar station when it needs at least three or four such stations throughout the country. Upreti says repeated pleas to add more stations have always fallen on deaf ears. The reason is always the same: budget constraints.

“Our government buys fancy cars every five years or so but doesn’t have money to spend on something that could potentially save thousands of lives. This sad reality is proof of an apathetic system,” says Upreti.

Not all’s lost

To give credit where it’s due, Upreti adds the Department of Hydrology and Meteorology (DHM) under the Ministry of Energy, Water Resources and Irrigation, is currently doing a much better job than it has since its establishment in 1962. But they are still hamstrung by lack of equipment and investment.

Hydrologist at the department, Bikram Shrestha Zoowa, agrees but says though there have been many improvements over the years much still remains to be done. Zoowa adds there is a need for more investment as well as capacity building to ensure water-induced disasters don’t leave a carnage in their wake.

According to Zoowa, those who work on the field are sensitive to the issue of floods and landslides and see the need to give it utmost priority. But at the decision-making level, there simply isn’t that awareness or a sense of urgency. In this case, he adds, local government authorities could look into the matter. The department could help with the required manpower and capacity building but the plan of action would be better off initiated and implemented at local level.

Upreti holds similar views. Every community, he says, should have many weather stations to measure temperature, wind, and rainfall and develop local early warning systems. So far Nepal has been measuring overall rainfall but there is also the need to identify flood/landslide prone areas and focus on collecting specific data for accurate prediction. With proper rainfall measurements in catchment areas and constant monitoring of river flow, settlements downstream will have ample time to move to higher grounds. It’s the failure to do so that has been taking away people’s lives and livelihoods.

Weather forecast, he says, could be compared to a blood test. Just as a blood test tells you much about the state of your body, weather forecast is the vital information that indicates and predicts a country’s condition. But Nepal hasn’t paid much attention to it, which is evident by the number and scale of disasters that happen every monsoon. Weather and hence natural calamities could be predicted very accurately if long-term data were to be available.

Time for action

According to Samir Shrestha, meteorologist at Meteorological Forecasting Division under the DHM, there are chances of heavy rainfall in upcoming weeks, though their frequency and intensity could decrease. However, there is still a high risk of floods and landslides because river levels will continue to rise and the soil is already saturated, meaning it can’t hold more water. Based on predictions, the division will continue to issue alerts 24 to 48 hours prior to the possibility of a natural calamity but, Shrestha says, warnings are futile when proper measures aren’t in place.

“There is a need for policy-level changes because every monsoon brings floods and landslides and, with them, destruction of property and loss of lives,” he says.

Upreti adds that climate change will only exacerbate the problem in the future. There will be more rainfall, it will inevitably be more intense and that will result in more floods and landslides. Not to forget, the massive earthquakes of 2015 have left fissures in and thus weakened many hills.

Cloudbursts that are quite common along the Himalaya, especially the Mahabharat range, also worry Upreti. In such cases, there is an excessive amount of precipitation in a short period of time that is capable of causing floods and landslides even if rivers are flowing their natural course and there is enough drainage. Cloudbursts are apparently quite frequent these days mainly due to climate change.

“The last cloudburst that caused massive destruction took place in 1993. But cloudbursts aren’t rare and if they happen when the ground is already saturated like it is now, then there will be massive damage,” says Upreti.

Another problem lies in the way Nepal has always approached disasters. We wait till something happens and then shift all the focus on rescue and relief. Post disaster trauma and loss could be significantly minimized if disaster prevention and mitigation took precedence over post-disaster management. But that is rarely, if ever, the case.

Dilip Kumar Suwal, an official at Bhaktapur Municipality, says we have to learn from past mistakes and do whatever it takes to prevent disasters. The condition in Nepal is already precarious without human behavior and developmental programs worsening things for us.

The 2018 Hanumate flood was a result of drainage channels being blocked by boundary walls and river bank encroachment that obstructed water flow during the monsoon. Similarly, there’s haphazard road construction and sand extraction in the Chure that weaken hilly areas and make them landslide-prone. In Kathmandu valley, there is also the risk of urban flooding due to improper drainage systems and sewage channels opening into rivers.

“Natural reasons for flooding like rainfall can’t be helped but communities can ensure reckless human behavior doesn't aggravate the problem,” says Suwal. After the flooding of Hanumante River three years ago, the local authorities have been trying their best to ensure there is no narrowing of the waterway. They are also building proper embankments and removing debris and mud from the bottom of the river.

Upreti appreciates local level works but laments that such piecemeal measures won’t make much difference when the entire system is faulty. The communities’ efforts need to be supplemented with additional manpower and infrastructure at the national level. And the time to start working on it isn’t when the next monsoon rolls around. It’s now.

Superheroes | The forgotten soldiers: Kathmandu’s trash collectors

A shrill whistle goes off as you are sitting down with your morning cup of steaming milk tea. You sigh in relief. You had started becoming slightly concerned about the overflowing trash can near the main gate. Someone is finally here to empty it out. You take a sip of your tea and pick up the newspaper.

Perhaps a similar scene plays out in most households of Kathmandu that, according to Solid Waste Management Association of Nepal, collectively generate 1,200 tons of waste a day, of which 65 percent is organic waste and 15-20 percent is recyclable. And handling our waste are around 4,000 laborers from 75 private companies and municipalities.

Kathmandu’s inability and unwillingness to segregate its waste—resulting in trash collectors having to lug heavy loads and worse, suffering cuts and injuries because of broken glasses and such—has always been glaring. But waste-pickers say that is nothing compared to how undignified their job feels. Chalk it up to the public’s attitude towards them, or the companies they work for always telling them to cater to each household’s demands and rarely ever addressing their woes, theirs is a thankless job.

“I have become accustomed to people calling me ‘fohor bhai’ and even scolding and screaming at me,” says 38-year-old Surendra Bhusal. He has been working as a trash collector in Kathmandu for a decade and, in those 10 years, not once has anyone said a kind word to him. Waste-pickers, he laments, are often treated like trash because they work with trash.

The mindset reflects in our actions. Most of us aren’t conscious or a little sensitive about what we are throwing and the fact that someone, an actual person, will have to manually sort through it. Bhusal says there are often soiled pads, broken shards of glass, kitchen waste and plastic cold drink bottles all in the same bin or plastic bag. It makes their jobs more difficult and fraught with risks. There have been times when dirty water and slime have splashed onto Bhusal’s face and clothes. It makes him feel like the lowest of the low in society, he says.

What’s worse, says 39-year-old Khadga Bahadur, is that there is no solidarity among workers which makes it difficult for them to campaign for their cause—dignified labor, sensible work hours, better pay, and health insurance.

Bahadur, who has been on the job for 16 years, works for 12 to 13 hours a day (out of which four to five hours are spent walking from one place to another), with a one-hour lunch break in-between. On average, he visits 400 to 500 houses and in half of those places he has to go inside to collect the garbage. This makes his work tedious, confusing, and time-consuming.

“Our job comes with many hidden costs. We regularly suffer from small injuries and diseases. After many years in the job, most of us develop long-term health issues,” he says. However, neither the public nor the government seem concerned and trash-collectors, without whom our households simply wouldn’t function, find themselves in a quandary. Their livelihoods depend on their ability to work but the work they do puts their health at stake.

The Covid-19 pandemic worsened their already dire situation. As essential service workers, waste-pickers have had to put aside their fears of contracting the infection and taking it back home to their families. While some have been given masks, gloves, and boots by their companies, most have had to buy their own protective gears.

Prakash Pariyar, 49, says a few of his colleagues have contracted Covid-19 but they didn’t get any financial assistance whatsoever. The hospital bills have created a dent in their savings, one they will never be able to recoup. As frontline workers, they were to receive the vaccine at the same time as police officials. However, none of the 10 trash collectors ApEx spoke to had been vaccinated. They also don’t know of anyone in their circle who has received even a single dose of the vaccine. This is when many other frontline workers—doctors, nurses, drivers, deliverymen, etc.—have taken both the prescribed doses.

“We are the nation’s forgotten people. No one cares about our wellbeing. We are as disposable as the garbage we get rid of,” says 42-year-old Bhim Bahadur Gurung. He doesn’t want to make a fuss because he knows nothing will come out of it. But he wishes to get vaccinated: Forget putting his loved ones at risk, if he contracts the infection and isn’t able to work, how will his family of five survive?

Pariyar has given up hope that their situation will improve. It’s not going to happen, at least not in his lifetime. Of that, he is sure. For 22 years, he has worked relentlessly from 5:30 am till 7:00 pm or later but the long hours he has clocked in haven’t amounted to much. There is no financial security; everything he earns is spent running the household. He isn’t a valued member of the society; most people hurl abuses at the slightest mistake and not one person knows his name. Everyone simply calls out to him as ‘fohor’, ‘oye’ and very rarely, ‘dai’.

“Some households gave us food supplies and cash during the previous lockdowns. But this time everyone is scared to have any kind of contact with us because the virus is said to be highly infectious,” says Pariyar.

What saddens trash collectors, however, isn’t that no one has come to their aid at such troubled times but the fact that they are still expected to carry on as if everything is okay all the while being acutely aware that they are feared as virus carriers. Some literally run away when they arrive while others shout instructions from the rooftops of their homes. Bhusal says they are made to feel both wanted and unwanted at the same time. Though if trash were to magically disappear, the society would pretty much wish their existence away.

Sanjay Khatri, 25, says the situation wouldn’t be so bleak if every household at least put their trash-cans outside their gates. It’s okay if they don’t want to throw their garbage in the collection vehicle themselves, he says. But the mere suggestion of that more often than not leads to a stream of accusations and insults. They are told they aren’t doing their jobs properly and threatened with disciplinary action from their offices.

“There are so many problems in our line of work that I don’t even know where to begin. It’s best I turn a blind eye and just carry on. Otherwise, it’s too hurtful,” he says.

Is your food organic? Probably not and it probably doesn’t matter

A medium-sized bunch of lettuce costs Rs 30 at the local vegetable market. The organic version of the same, depending on the seller, is priced anywhere between Rs 75 to Rs 150. These days, many people prefer the latter because organic food is supposedly free from pesticides, nutrient-rich, and thus healthier. But is it really as good as we think it is? Experts say there actually isn’t much nutritional difference between organic food and their conventional counterparts.

Dietician Kala Nepal says the impact of organic food on health and disease prevention isn’t significant. Various studies suggested people who consumed organic food have relatively lower risk of heart disease and skin problems but the subjects also followed better lifestyles. Nepal says good health in such cases cannot be attributed to the consumption of organic food alone.

Kala Nepal

“There have been quite a few studies examining the macro- and micronutrient content of food. The vitamins and minerals content are found to be similar in both organically and conventionally grown food," says Nepal.

Food, according to Nepal, needs to be affordable and accessible. While choosing what to eat, we have to factor in its practicability. It’s not possible to get organic versions of everything we eat on a daily basis. Organic food is also more expensive. There are a number of reasons for that: There is less production, it needs more manpower, and it costs money to get certified as organic. Is the extra expense worth it? The answer is no.

Anushree Acharya, dietician and MD, The Nutrition Cure Nepal, says most of us are just paying for the ‘organic’ tag. There are some companies that are following the required protocols but many others are just labeling their products organic to sell them at higher prices. Unfortunately, there is no way to tell what’s genuine and what’s not.

Anushree Acharya

Anushree Acharya

According to Mohan Krishna Maharjan, senior food research officer and spokesperson at Department of Food Technology and Quality Control, there is no monitoring of the organic market in Nepal. The government has set some guidelines for organic food production and organic products do need a third-party certification. The thing is, no one checks if companies are following the rules.

Maharjan explains growing organic crops involves managing many external factors. The soil has to be pesticide-free for a certain number of years and the environment has to be an isolated one. If you are growing something without synthetic fertilizers at a certain place but pesticides are being used in the surrounding areas, then your crops aren’t organic.

Food technologist Ujjal Rayamajhi says there are a few organic farms in Kathmandu that are abiding by at least some government-set criteria but then again there is no monitoring to guarantee full compliance. Also, the government is trying to support those that follow good agricultural practices. But there is a need for proper rules and regulations to make sure the organic food available in the market today meet the required standards. Unless there’s a system in place, the public runs the risk of paying high rates for substandard products.

Ujjal Rayamajhi

Ujjal Rayamajhi

Our focus in the meanwhile, dietician Acharya says, should be on eating healthy by using what’s locally available to us rather than letting our food choices be driven by marketing gimmicks. Acharya sees a lot of people having organic teas or certain seeds (like flax and chia seeds) because the packaging declares it’s good for such-and-such conditions or because someone they know vouches for its efficacy.

News of pesticide-laden fruits and vegetables in the market also fuel our interest in organic produce. Experts say that though this is something the government needs to look into to ensure public safety in the long run, there really is no need to be alarmed and completely switch to organic food.

What we need to understand, they say, is that growing and preserving crops without using chemical fertilizers is almost impossible today. There is also a toxicity limit to the use of pesticides in agriculture and as long as that is followed conventionally grown food is safe for consumption.

There are also, says Nepal, simple ways to lessen the pesticide content in our food. Soaking grains, fruits and vegetables in a solution of baking soda is effective in removing much of the pesticides present in them. Similarly, Acharya adds you can immerse food in salt water for at least 15 to 20 minutes to let toxins leach out. Other ways to remove toxins from food include scrubbing your produce and cooking without a lid on.

Aarem Karkee, dietician at Patan Hospital in Lalitpur, says the main dietary issue we need to focus on isn’t whether we are eating food that is grown using pesticides and synthetic fertilizers. The top 10 reasons for mortality, including heart diseases, diabetes, and cancer, are all linked to our consumption of refined and fast food. The emphasis, he says, should thus be on changing the kind of food we eat—meaning we should eat more whole foods rather than the processed and packaged kind.

Aarem Karkee

Aarem Karkee

“If you ask me whether you should be eating greens that you know have been sprayed with pesticides, then my answer is a resounding yes,” says Karkee adding that the benefits of having fruits and vegetables, despite their chemical content, far outweigh the risks.

Fellow dieticians Acharya and Nepal both agree with Karkee and say the key to eating healthy lies in making sensible food choices. Eating what’s in season is also one way of a relatively toxin-free lifestyle. So is understanding your food: Produce with thicker skins tend to have fewer pesticide residues. The thick skin or peel protects the inner fruit or vegetable. If you remove the skin or peel, then you are essentially removing much of the residue.

Nepal also mentions that we tend to choose fruits and vegetables that are glossy and don’t have a single mark on them but that’s not really what you should be doing. Instead, she suggests, look for ones that aren’t so perfect. If you see insects or some damage, that’s an indicator that they were cultivated using less fertilizers and chemicals.

Further, Acharya adds that there are many practical ways in which you can have a toxin-free, healthy diet. You just have to be willing to look beyond the fads and experiment with different types of food as well as be a little aware about the kinds of nutrients available in different kinds of products. For example, she says, it’s not necessary to have avocados and nuts for your daily dose of omega-3s. Ghee and cooking oil (like olive oil) are also great sources of unsaturated fatty acids.

“Eating organic food isn’t the ultimate way to good health as it’s often made out to be these days,” she concludes.

Unfamiliar territory: Navigating the lockdown

It’s 5 am. After a steaming cup of ginger-infused tea (made by his wife only on his lucky days), he will leave home. He will have a small cup of milk tea at the Patan Durbar Square chowk, chatting with other early risers whose mornings, like his, are incomplete without a walk, and then pick up some fresh greens on his way back. It’s been a ritual for as long as he can remember.

Only now, he will have to settle for a quick stroll around the neighborhood. The mask fogs his glasses and makes it hard for him to see. He doesn’t meet anyone and there aren’t any local vendors selling vegetables in the area. The medical doctor in his late 60s says it’s a huge deviation from his earlier relaxing routine. It’s annoying. It’s upsetting. And it doesn’t set the right mood for the day.

Many people ApEx spoke to confessed feeling ill at ease as their daily routines have been thrown out of whack. They know it’s necessary to stay at home. But being thus confined brings about a sense of helplessness, one that’s difficult to shake off.

“I miss my daily vegetable run,” says Lok Raj Pant, 63, who has always woken up at the break of dawn and gone on a walk. Like the doctor, he too enjoyed buying vegetables during his daily morning excursions. It might seem like a small thing, he says, but its implication on his life was immense. It gave him a sense of purpose and kept him disciplined. A good life is, after all, the cumulative effect of little things, he adds.

Lok Raj Pant

For those like Pant who have led active lives since their 20s, to suddenly find themselves without much to do has been a difficult terrain to navigate. Pant was involved in the hotel industry for nearly 40 years before he retired to work on his own projects. He was doing what he loved and living the life he wanted till the pandemic forced him to readjust. And he doesn’t like it, not one bit.

“I miss my routine and my social life. I feel trapped. It’s discomfiting,” says Pant.

Madhab Lal Maharjan, 70, owner of Mandala Book Point in Kantipath, Kathmandu, says it’s been a hard time for all but more so for people his age. They have had a certain lifestyle for so long that readjusting to the ‘new normal’ hasn’t been easy. But Maharjan believes in looking at the brighter side of things. He is grateful that his family is safe and that he gets to spend lockdown in the company of his grandchildren, who he never got to see as much before.

Technology, he believes, has made it easier to cope. If the pandemic had struck say 30 years ago when there were no cellphones it would have been almost impossible to stay sane. Just the fact that he can talk to his loved ones and even see their faces whenever he feels like it has made it possible to stay upbeat.

Maharjan’s daily routine included meeting a lot of different people, from various fields—mostly those who used to regularly gather at his bookstore in the evenings. They have, over time, become his friends. He misses not being able to talk face-to-face about current issues, books, and life in general. But they still keep in touch with regular phone calls and zoom sessions and that, Maharjan finds, calms his nerves and fills him with hope.

“Cribbing and complaining about what could have been will only make things worse. The focus should be on keeping yourself occupied and trying to enjoy your time at home,” he says.

That is exactly what Jayendra Rimal, chief operating officer, Leadership Academy Nepal and adjunct faculty for management, has been doing. The pandemic has brought about a drastic change in his lifestyle. He has had to forgo his morning walks and table tennis sessions. The shift to online teaching has also been a bit jarring. Rimal, who is nearing 60, prefers interacting with his students in an actual classroom.

Jayendra Rimal

“There’s a lot you can tell about your students from their expressions and body language. You know when they are bored and it’s time to crack a joke. This kind of laidback approach to teaching isn’t possible when you are conducting online classes and I really miss that,” he says.

It’s very easy to get caught in the trap of wishing for things you don’t have at the moment, he says. He says boredom, loneliness, and confinement have also brought about a cognitive deficit of sorts. To keep his morale up in these scary times, he has been reading more than ever before, listening to podcasts, and meditating. Also, the weekly online-guided meditation program he takes part in helps bring clarity and peace of mind.

Pant argues that for those who don’t read or have specific things to do, it can be a little tricky to pass time and that can often lead to a tense environment at home. Pant tries to read and his daughter is always recommending books. He takes long naps. But he finds that just messes up his sleep cycle.

Pratima Tamrakar, psychotherapist, advises picking up a hobby and being involved in chores. The problem in our society, she says, especially where the older generation is concerned, is that men have never helped out at home. Chores are considered a woman’s job. It’s time to change that and involve men in housework, she says.

She suggests having one proper meal together as a family to instill a semblance of normalcy in life. In many families, she says, people are eating alone, at their own preferred timings and that is creating a distance among them. This is further fueling a sense of unease on a subconscious level.

Rimal agrees that the need of the hour is to respect one another’s sense of space while also being able to come together as a family. It also helps if you realize and accept that life will invariably bring a lot of surprises and not all of them will be pleasant.

Pant says the shift from normal routine is just something all of us have to deal with, one way or the other—if not for ourselves then for the sake of our loved ones. The sooner we make peace with it the better, he says. And, as Maharjan puts it, whining isn’t going to change a thing so you might as well make the most of it.

Reading during the pandemic: An act of self-care

I’ve always loved to read. The first book I read by myself was probably the Ding Dang Dong series which was published in 1985. They were short tales of three monkeys who got into hilarious situations but each book also had a moral lesson. This was followed by Aesop’s Fables, a collection of stories by Aesop, a slave and storyteller in ancient Greece.

As a child, my sense of right and wrong mainly came from the stories I was told and read. Stories I heard were from the Panchatantra, Mahabharata, Akbar and Birbal, and Grimms’ Fairy Tales. These stories were, now that I know better, tweaked to fit my parent’s changing ideas on how to raise me right.

The stories I read, on the other hand, weren’t always as black and white or centered on the need to be good. Enid Blyton’s books made me jump from compound walls I was forbidden to climb and fill my pockets with stones before getting on the weighing scale to freak my mother out. Roald Dahl’s books showed me there was fun in being mischievous—that mischief wasn’t as bad as it was made out to be. For the longest time, I believed I could be Matilda, that I could harness my mind’s power to move things like she did in Dahl’s classic by the same name published in 1988.

Books made me climb out of a ditch (that I had gotten into in the first place to prove some boys I could be like them), jump from the rooftop of one truck to another at my grandparent’s home in Hetauda, and venture on mini-excursions of my neighborhood, pretending to be Nancy Drew. In hindsight, books made life exciting by giving wings to my imagination and, in the process, teaching me things I wouldn’t have learnt otherwise.

Now, with the exception of politics, there isn’t anything I don’t read. But fiction is what I turn to when I’m in need of a pick-me-up or am unable to make sense of things. It’s comforting to get lost in another world when you find yourself stuck where you don’t want to be.

Stories are what kept me sane during the 2020 lockdowns, and what is helping me manage stress right now. And, indeed, many of us have turned to books for comfort, distraction and escape in a tremendously upsetting time. Rojita Adhikari, a freelance journalist, says she reads to forget the pain she is going through. Adhikari is recovering from covid and is still weak and a bit scared. Reading, she says, is a great distraction and helps calm her nerves.

Adhikari feels she narrowly escaped death. Her condition deteriorated after a week of being diagnosed, and she considers herself lucky to have pulled through. Though she is much better now, the thought of what could have been haunts her. That is when she turns to books. Even reading for 15-20 minutes is enough to change the course of her thoughts.

Similarly, a school friend, Sanyukta Rajbhadari, says reading is like meditation. Books, she says, transport her to a different time and era and she finds some much-needed solace in these unprecedented times. She is a doctor and work can be a little too demanding, which is why she reads—to shift her focus for all that stresses her out.

Sanyukta Rajbhandari

Sanyukta Rajbhandari

“I just finished reading The Mermaid and Mrs. Hancock by Imogen Hermes Gowar and it took me to 18th century Gregorian London. It was just what I needed to escape reality and recharge,” says the self-confessed book hoarder. The sight of books, she says, is enough to make her smile.

I could relate to her because when it gets a bit much, as it often does these days, I find a story can take you to a place where your problems don’t exist anymore. It has become so essential to be able to turn off that mental switch and there really is no better way to do it than by reading.

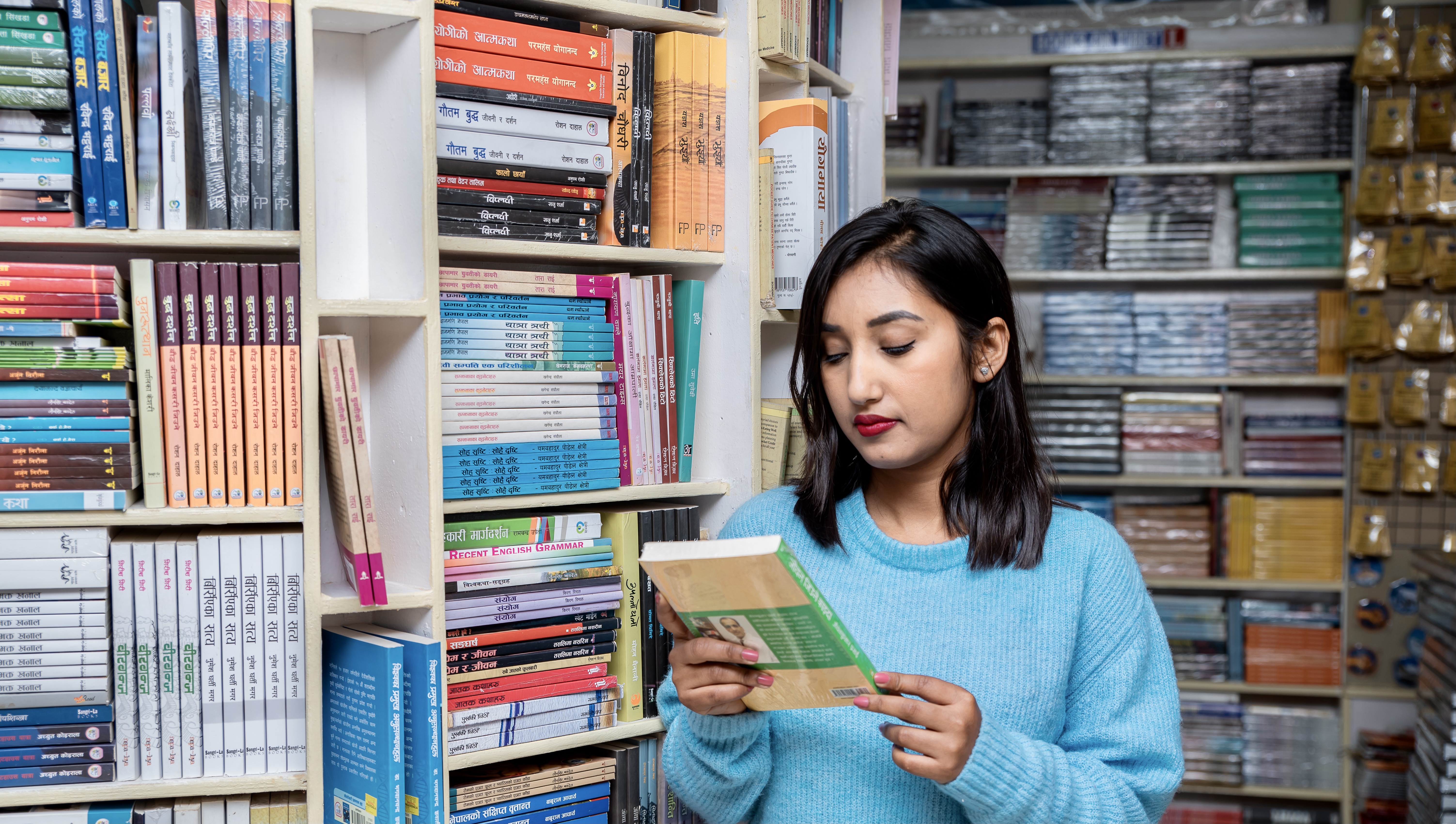

Prajjwol Kunwar, founder of Laibary, an online bookstore, says people are definitely reading more during the pandemic. Orders have increased and though Laibary isn’t currently delivering books, there is a steady stream of enquiries from customers. Pratima Sharma, online sales and marketing officer, Nepal Mandala Book Shop, says they too are getting constant requests from customers to resume delivery, and they are considering it.

Pratima Sharma

Pratima Sharma

Prajjwol says he is reading more than ever before. He also has the time to be a bit indulgent with his reading habits. Meaning, he lets one book lead to another—choosing to do in-depth research about topics he is interested in which, at the moment, is mythology. Pratima claims her reading habit has been a boon during lockdown. Books help her disconnect and don’t let her mind wander pointlessly.

A 2009 study at the University of Sussex found that reading can reduce stress by up to 68 percent. The study found that individuals who read for as less as six minutes had slower heart rates, less muscle tension, and lower stress levels. The neuroscientist who conducted the study reported that “reading is an active engaging of the imagination that stimulates your creativity and causes you to enter what is essentially an altered state of consciousness.”

Stories that mirror your feelings calm you down because you realize your experiences aren’t unique and that is immensely comforting. It also helps to explore possible fictional scenarios related to your problems by stepping into the character’s shoes. I recently read The Pull of the Stars by Emma Donoghue, a novel based on the 1918 influenza-pandemic. It’s grim and heartbreaking but the story mimics the present-day Covid crisis and makes you feel a little less alone and doomed.

The book also made me a little less angry—at the politics that’s still going on despite the health crisis we are facing. There’s a chapter where a character criticizes the government for Dublin’s poverty and high infant mortality. Another says she doesn’t have time for politics which gets the reply, “Oh, but everything’s politics, don’t you know?” Seeing how some things are a constant no matter where in the world you are lessened my sense of injustice.

What’s more, I find reading can sometimes foster a sense of community with other readers as well as the characters in the book and that is more crucial today than ever before. I might not be able to meet anyone but the conversations I’m having with people, because of our shared interest in books, have helped me connect with them on a deeper level.

Here, I must also confess that sometimes reading feels like a luxury. There’s a sense of guilt about not being prudent with my time by helping those in need. But what the pandemic has also taught us is to take care of our mental health and practice self-care. And reading is the only way I know how to do that.