Nepal has set the target of net-zero emissions by 2045. It’s an ambitious, but not an impossible, goal—if only the government had a good energy policy, say energy experts.

Multiple actors are attached to Nepal’s energy sector and they are all working with separate visions, policies and priorities. There is no umbrella policy and no apex institution to give them direction.

Madhusudhan Adhikari, executive director of Alternative Energy Promotion Center, says policy-makers are themselves misguided.

“They think energy means exclusively electricity when the contribution of electricity in our energy mix is under 10 percent,” he says. “When we discuss energy in Nepal, we are debating that small percentage.”

Nepal’s key sources of green energy are hydro, solar and wind. Until now they are independent of one another. Companies and institutions engaged in the production and distribution of energy are not working with a single purpose.

To achieve net-zero, policymakers should be thinking about phasing out fossil fuel and biomass, as well as increasing domestic consumption of clean energy and exporting surplus energy. There is a desperate need for better coordination among government agencies.

In 2017, the Asian Development Bank advised the Nepal government to formulate and implement a national energy security policy. The need for such a policy had become vital, particularly after the country adopted a three-tier government system.

Nepal’s current energy policy places hydropower at the top. This approach needs to be re-oriented as the country is not sufficiently utilizing modern and clean energy.

“We have the Energy Ministry but it largely functions as a hydroelectricity ministry,” says Adhikari. “This shows a lack of clarity in vision.”

The electricity sector isn’t faring well either. The Nepal Electricity Authority (NEA), the state power utility, hasn’t been able to provide enough electricity in rural areas. Electricity distribution through transmission lines in some topographically challenged mountain and hill areas is either impossible or highly expensive.

This is where alternative energy could have filled the gap.

The onus for formulating a comprehensive energy policy lies with the Ministry of Energy. But the task is almost impossible due to frequent government changes. Successive energy ministers are keener to announce populist agendas instead of working on a long-term policy.

The National Planning Commission and Water and the Energy Commission are also responsible for guiding the government. Yet these two bodies have done little to review Nepal’s energy policy in line with the changing needs.

“The priority is mostly hydro and then solar,” says Shailesh Mishra, chief executive officer of Independent Power Producers Association. “There hasn’t been much deliberation on an umbrella energy policy.”

During the Panchayat regime, Nepal had no energy policy. It was the NEA’s responsibility to manage the country’s hydropower. In 1992, the Hydropower Development Policy was formulated, with the prime objective of motivating the private sector to invest in hydropower development.

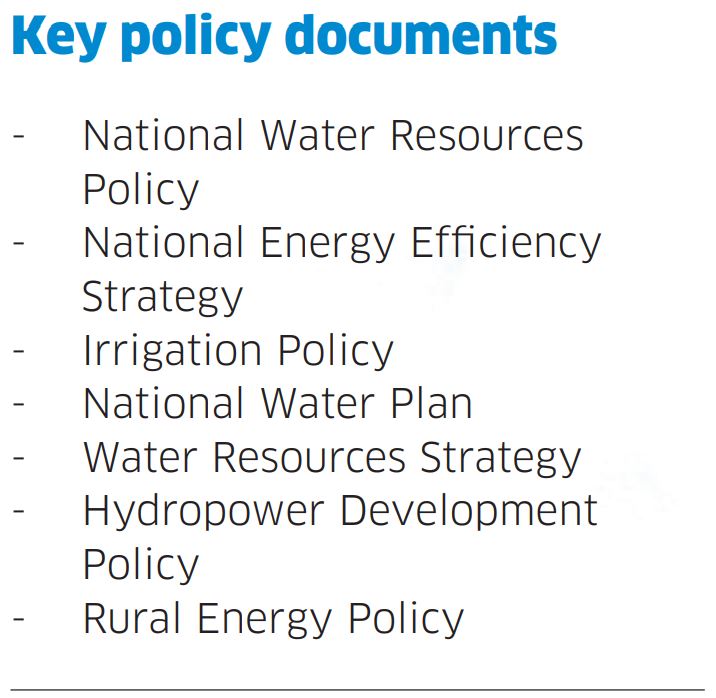

The hydropower policy more or less remains Nepal’s only energy policy. Some key policies that the government has introduced over the past three decades were also related to hydro, such as the National Water Resources Policy, the National Energy Efficiency Strategy, the Irrigation Policy, the Nepal Water Plan, and the Water Resources Strategy.

Talks about policies for other sectors began in earnest in the 2000s. In 2006, the Rural Energy Policy was promulgated to provide biomass technologies and off-grid micro-hydro systems for rural electrification. Later, there were initiatives to explore alternative energy sources in solar, wind biogas and micro-hydro.

It was only in 2013 that Nepal introduced its “energy vision” that talks about integrated policy to handle the energy sector.

“Discover, explore, develop and manage sustainably all the available potential energy resources in the country,” says the document. It also points to the need for a “high-powered umbrella organization” to implement a uniform energy policy, as well as a national energy regulatory commission to coordinate with all state agencies.

Maheshwor Dhakal, joint secretary at the Ministry of Forest and Environment, points to an urgent need for a comprehensive energy policy in order to phase out the use of fossil fuels and switch to clean energy.

The absence of such a policy, he says, signals an abject lack of coordination among key state institutions in the energy sector.

“Along with the policy, Nepal also needs a separate ministry to look after energy-related issues, particularly as we have already pledged to embrace green energy,” adds Dhakal.

Krishna Prasad Oli, a former National Planning Commission member, however, faults the lack of coordination rather than the energy policy per se.

He says before initiating any homework on an integrated energy policy, there should be a comprehensive study on possible areas of improvement.

“Let’s first identify the bottlenecks,” he says, cautioning against jumping to a conclusion that a single policy will resolve everything.

Oli strongly believes that the heart of the problem lies, again, in lack of coordination and regulation. “A letter from Nepal Electricity Authority takes a whole month to reach the Energy Ministry. Many such lapses have gone unaddressed.”

Oli also advises energy experts and policymakers to consider energy security that has been given very little thought.

Nepal relies heavily on imported fuels, but there is as yet no plan to prevent the kind of acute energy-insecurity seen post-2015 blockade.