The South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) was formed to overcome common regional challenges like pervasive poverty, under-development, and lack of jobs.

Since its inception in 1985, geopolitics in the region and the world at large has drastically changed. But SAARC has made little progress in this time as its key objectives remain unfulfilled.

The 19th SAARC summit, scheduled for Pakistan in 2016, was cancelled after India accused Pakistan of a “terrorist attack” on its soil. The regional body has since been moribund.

Cold War impetus

The Cold War was instrumental in SAARC’s formation. Many regional organizations came into existence at the behest of the Western world at the time, including the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). The formation of this Southeast Asian body in 1967 added to the impetus for a similar regional body in South Asia.

In his book ‘Regional Cooperation in South Asia Emerging Dimension and Issues’, Prof BC Upreti of India says that during the Cold War both the US and the USSR encouraged countries across the world to build regional organizations to increase their influence.

Backed by Western countries, many regional organizations such as the Rio Pact, the Organization of American States in Latin America, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), and the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization came into being at the time. Their main objective was to protect their politico-strategic interests and to contain the Soviet influence, Upreti writes in his book.

The Soviets also supported the formation of regional bodies of its allies like the Warsaw Pact in Eastern Europe. The two sides in the Cold War wanted to increase their influence through these regional organizations. And the US in particular was keen on getting the countries in South Asia to form a regional organization.

Foreign policy expert Dev Raj Dahal says the talk of regional bodies gained momentum in South Asia in the 1970s.

“The US urged the countries of this region to form a regional body. It first helped form SAARC and later to bring in Afghanistan as its member,” Dahal says.

But it was only in 2007 that the US formally joined SAARC as an observer country. Since then, the US has been continuously expressing its readiness to work on regional integration and connectivity.

China became a SAARC observer country in 2005. It too had of late shown an interest in the regional body, perhaps to expand its sphere of influence in the region.

The other SAARC observers are Japan, South Korea, Myanmar, Mauritius, Iran, Australia, and the European Union.

Regional necessity

The formation of SAARC, however, wasn’t just predicated on Cold War-era politics of regionalism. Its existence was also necessitated by the fact that small South Asian countries needed recognition on the global stage in order to tackle their socio-economic problems. Formation of a community of nations with common interests, they reckoned, would strengthen their voice on the international arena. Together, they could fight poverty and underdevelopment.

Initially, it was Nepal and Bangladesh that strongly pushed for an inter-governmental regional organization at various regional and international platforms, says Dahal.

Addressing the 26th Colombo Plan Consultative Committee Meeting in Kathmandu in 1977, then King Birendra had proposed a regional body to utilize Nepal’s untapped hydropower potential.

At that time, King Birendra had also talked about incorporating China into such a regional body.

But it was then Bangladeshi President Ziaur Rahman who first took the initiative to form SAARC.

Lailufar Yasmin , professor at University of Dhaka, says as a newly independent country, Bangladesh espied the vulnerability of the regional architecture as India and Pakistan were looking beyond the region to ensure their security.

“Bangladesh felt that a stable and powerful South Asia was required to ensure its own development. The idea was later crystalized in the organization of SAARC,” she says.

The idea, she adds, was driven by the concept of regional co-development: if the region is not consolidated, went the idea, its countries could never achieve their potential.

Rehman floated the first concrete proposal before other countries in the region on 2 May 1980. Before that, he had proposed the idea to the then Indian Prime Minister Morarji Desai in 1977. He had also shared it with the leaders of Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka during his visits to these countries.

Moonis Ahmar, a Pakistan-based expert on international relations, says formal negotiations among countries to form SAARC began in early 1980s.

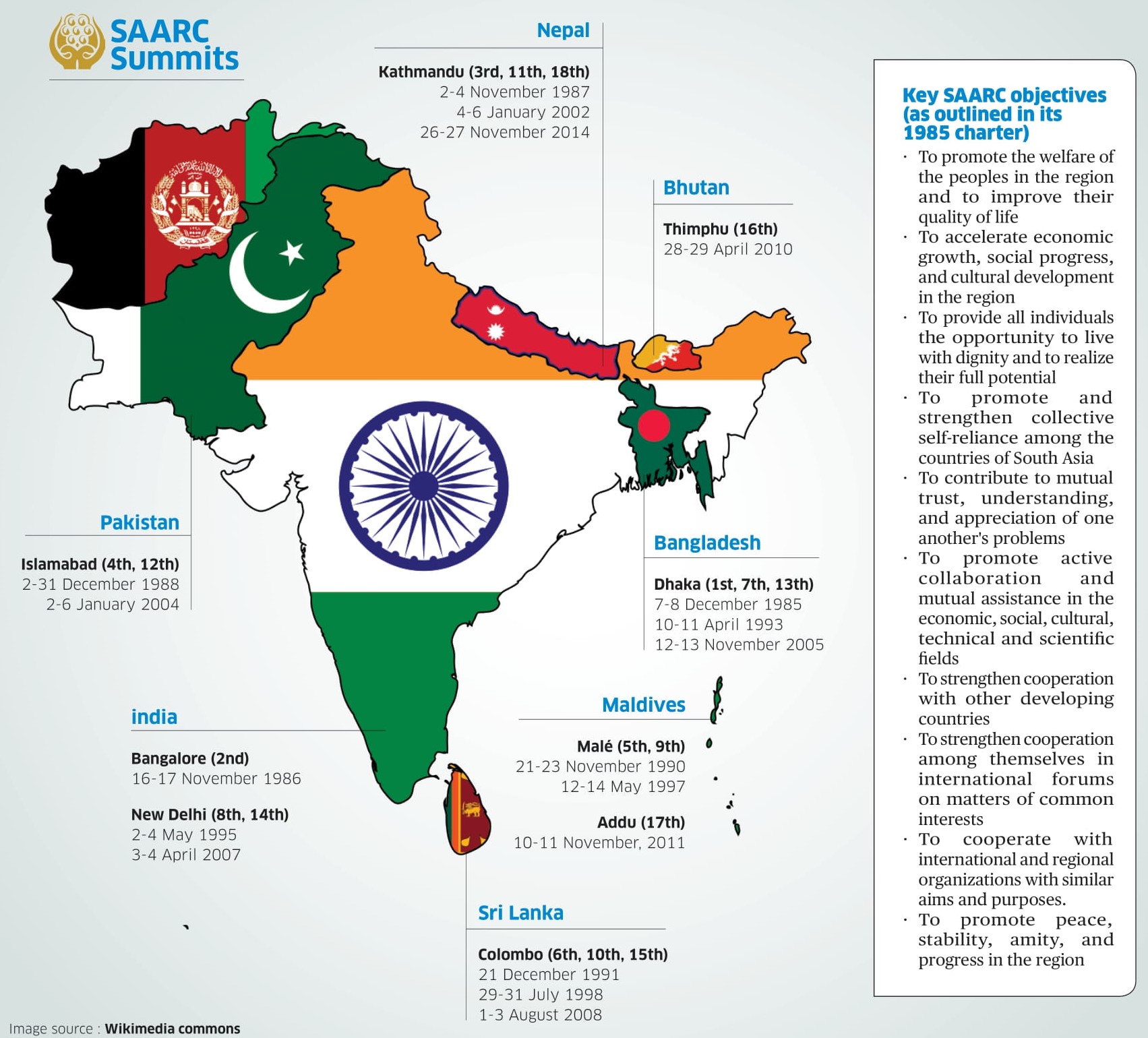

“The first meeting of foreign secretaries of South Asia was held in 1981 and the first meeting of foreign ministers in 1983, leading to the first summit of the regional body,” says Ahmar.

At first, both India and Pakistan were skeptical. India was suspicious that smaller countries in the region could use the regional body to gang up against it. Pakistan, on the other hand, saw SAARC as part of an Indian conspiracy to spread its influence in the region.

At the time, King Birendra had played a pivotal lobbying role. After Bangladesh floated the proposal, he dispatched foreign secretary Bishwa Pradhan to the countries in the region to lobby for the formation of SAARC.

In 1980, the foreign ministers of all seven countries met on the sidelines of the United Nations General Assembly and agreed to prepare a concept note for SAARC.

While preparing the note, the concerns of India and Pakistan were assuaged by picking non-political and non-controversial areas for regional cooperation.

After that, there were a series of meetings to hash out the nitty-gritty.

According to former foreign minister Bhek Bahadur Thapa, King Birendra took the leadership for the formation of the regional grouping.

“Initially, India was reluctant to form such a regional body. It was concerned that smaller neighboring countries could use SAARC to exert collective pressure on it on select issues,” says Thapa.

But King Birendra was dead against unequal treatment of small countries by big ones, says Thapa: “He wanted a regional body to overcome such unequal treatments.”

The collective spirit of small countries was amply reflected in the declaration of the first SAARC summit in Dhaka on 7 and 8 December 1985. It says: “They considered it to be a tangible manifestation of their determination to cooperate regionally, to work together towards finding solutions towards their common problems in a spirit of friendship, trust, and mutual understanding and to the creation of an order based on mutual respect, equity and shared benefits.”

Thanks to King Birendra’s active lobbying, member states also agreed to set up the SAARC Secretariat in Kathmandu.

Since its establishment, Nepal has been trying to make it a result-oriented organization. The country has also been serving as the chair of the regional body since 2014.

With the 19th SAARC summit indefinitely postponed over India-Pakistan tensions, Nepal has been urging the two countries to create a suitable climate for the summit. But nothing has come of it.

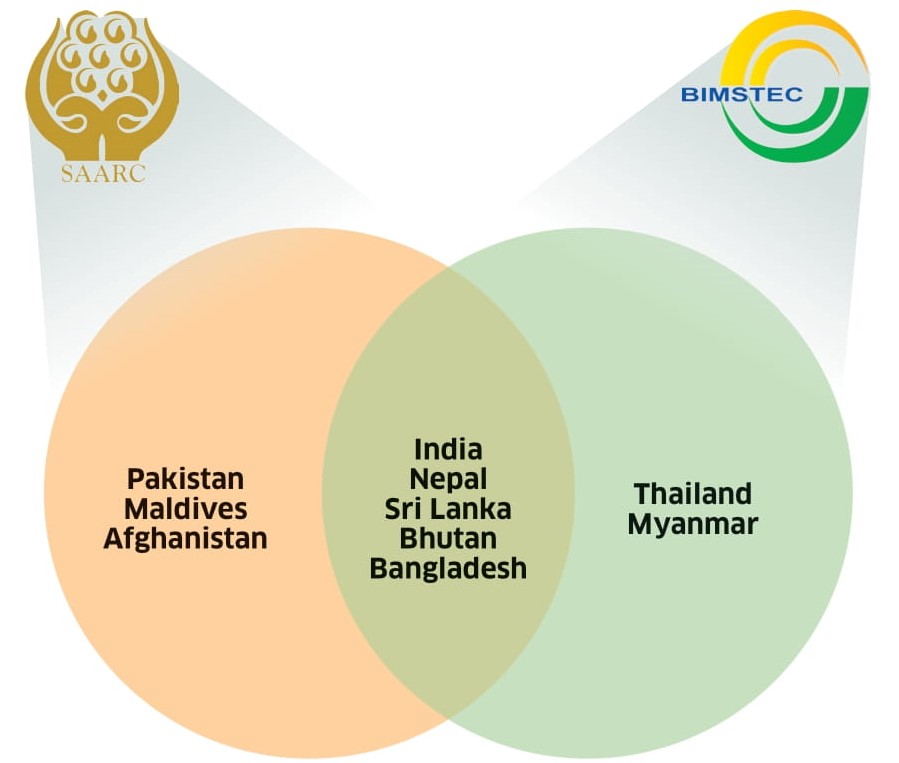

Pakistan has accused India of obstructing the SAARC process. India, meanwhile, doesn’t seem interested in taking SAARC forward. It has instead prioritized the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC), of which Pakistan is not a part.

Already, many Indian international relations experts and leaders see BIMSTEC, an international organization of seven South Asian and Southeast Asian countries, as an alternative to SAARC.