The 2015 constitution envisions local governments providing a range of affordable and timely public services. Responsibilities previously under the ambit of district administration offices or central agencies in Kathmandu are now handled by local units.

But as the sub-national bodies under the new federal setup complete their first five-year term, their performance has been mixed: some have done well while others are struggling.

According to a recent survey by the Commission for the Investigation of Abuse of Authority (CIAA), 67.3 percent of the respondents were satisfied with the services provided by their local governments. Only 11.2 percent expressed their dissatisfaction while 21.5 percent were neither satisfied nor dissatisfied.

The survey also suggests municipalities are performing better than rural municipalities, as the former are considerably better equipped both in terms of manpower and resources.

Federal affairs experts say as the first elected local governments under the new constitution, their five years were largely spent in infrastructure-building and capacity-enhancement. Their works, experts add, have laid a good foundation for the future.

Despite challenges, some subnational bodies still managed to do well.

The Municipal Association of Nepal ranked Waling and Putalibazar municipalities of Syangja district as the top performing local units in terms of service delivery and fiscal governance. Nilkantha Municipality of Dhading, Ilam Municipality of Ilam, Harion Municipality of Sarlahi, Tilottama Municipality of Rupandehi and Rapti Municipality of Chitwan were also on the association’s top municipality list.

Waling was recognized for its outstanding performance in service delivery through digital governance.

“In our municipality, people can access and pay for all services online,” says Mayor Dilip Pratap Khand.

Waling is also the first municipality in the country to pass laws and regulations required to implement the 22 exclusive rights the constitution provides to local governments.

To maintain transparency, the municipality discloses information about its services, activities, as well as incomes and expenditures. It has also developed a system to collect feedback on service delivery.

“We remove lapses in service delivery on the basis of the feedback we get from cross-party committees,” says Khand.

Some local governments like Bhaktapur Municipality proved their mettle during the pandemic. The municipal government, led by the mayor from Nepal Majdoor Kisan Party, provided door-to-door health services including PRC tests and built well-equipped quarantine centers in response to the pandemic.

In the past five years, judicial committees, led by deputy heads of local units, have also been instrumental in providing quasi-judicial services to the people. They are authorized to settle disputes in 13 specific areas, including those related to property boundary, canals, dams, road encroachment, wages, and lost and found cattle.

Most disputes settled by judicial committees have not been challenged in court—and that says a lot about their effectiveness.

But not all local governments have formed judicial committees owing to a lack of manpower trained in legal issues. Only 40 percent of local units have such committees.

Education is one vital area where progress in the past five years has been poor. Experts attribute this to the federal government’s reluctance to decentralize education as well as lack of local education laws, teachers and budget.

Still, some local bodies have set sterling examples by offering free school education.

Pyuthan Municipality of Pyuthan district provides free education up to the tenth grade. Its mayor, Arjun Kumar Kakshapati, says no children should be denied this basic right.

“Now all the children in the municipality go to school. We want the federal government to help us sustain our education campaign,” says Kakshapati.

Bhaktapur Municipality has also taken some notable steps in education, such as providing education loans and research funds.

Pyuthan and Bhaktapur are the outlier municipalities in education. Most local units are struggling due to inadequate resources and poor support from the central government.

According to the Ministry of Federal Affairs and General Administration, 87 percent of the local governments don’t have enough teachers.

Federal affairs expert Khim Lal Devkota says despite many challenges, there have been some positive changes in the state of education at the local level.

“Take the dropout rate,” he says. “The rate has come down thanks to initiatives like scholarships for children from marginalized communities.”

Besides education, local governments have also not made desired progress in health. Most of them still lack decent health facilities.

In the past five years, just 11 percent of local units built 15-bed hospitals, as required by the constitution. Government data shows that about 54 percent local governments are in the process of constructing such hospitals.

But even when hospitals have been built, they have lacked many basic health services. Lab services are generally poor and qualified and specialized doctors are in severe shortage.

Overall, some experts say while there is still a long way to go for the federal system to work smoothly, local governments have achieved significant progress in their first term.

Khemraj Nepal, a former government secretary, says local governments were concerned about the rights and plights of the marginalized groups, an issue that the central government largely ignored.

“Some local units in the Tarai have launched campaigns focused on the education of girls and children from marginalized groups,” says Nepal. “For instance these children are given bicycles to motivate them to go to school. These local bodies have also done a lot for senior citizens,” Nepal says.

His major gripe with local governments is with their manifest failure in stopping skilled manpower from migrating abroad.

Most local governments say inadequate infrastructure and resources mar their performance. They are short of human resources, including chief administrative officers, badly affecting service delivery. Dearth of staff means people are deprived of even basic services such as registration of life events, social security benefits, and recommendations for passports and citizenships.

Political disputes have also contributed to poor service delivery and dysfunction.

Over the past five years, dozens of local governments failed—some repeatedly—to bring their budget on time due to chronic disputes between municipal chiefs and their deputies. As many as 13 municipalities are yet to pass their budget for the current fiscal year.

According to a new study commissioned by the Ministry of General Administration and Federal Affairs, of the 753 local units, more than 200 have been operating under acting chief administrative officers. Works of these local units could be severely affected if these officers are transferred.

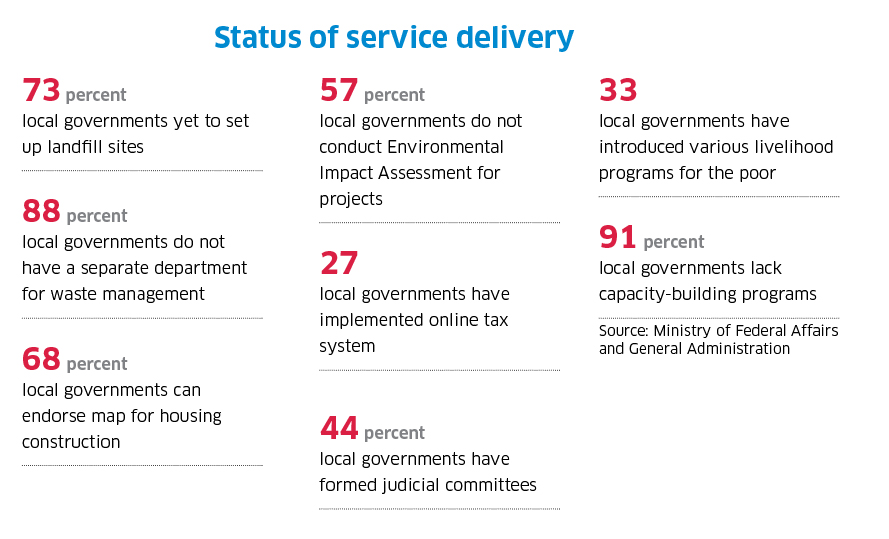

While local governments have taken the initiative to provide services, they have failed to make service delivery effective, says the study.

The ministry has recommended that the local governments invest in capacity-building and human resources.

Experts on federal affairs are optimistic that the performance of local bodies will improve.

“I’m happy with the overall performance of local governments in the past five years. Now we must focus on addressing the lapses in service delivery,” says Devkota.