In line with the inclusive principles enshrined in the Constitution of Nepal 2015, the three major political parties—in their recently held general conventions—included cluster-wise inclusion in their central committees (CCs). Yet while the inclusive principles were applied in selection of lower-level leaders, top positions continued to be in the hands of the traditional elite groups.

In its eighth general convention, CPN (Maoist Center) Chairman Pushpa Kamal Dahal ‘Prachanda’ admitted that inclusion compulsions had prolonged the party’s central committee selection. “Our inclusion system has drawbacks, and it has mostly to do with our policies,” he said before announcing the new central committee. Dahal claimed the party didn’t find a single Muslim woman to be inducted in the CC. The party, however, has tried to include more youths as each gender-ethnicity group has a youth component.

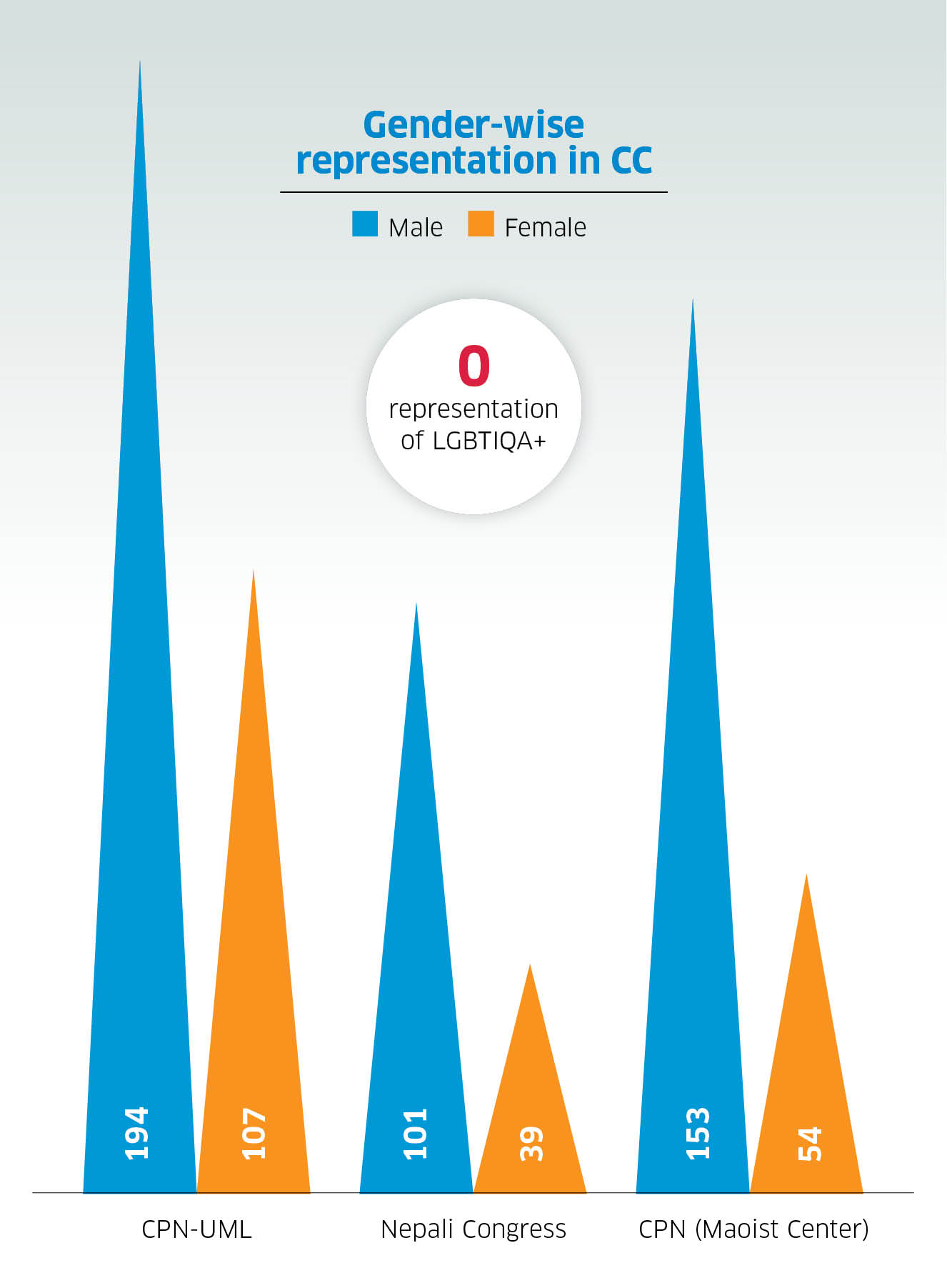

Other political parties have a similar story. CPN-UML has its new cluster named ‘[Kathmandu] valley special’ yet two of the members elected in it were from outside the Kathmandu Valley. The party doesn’t have a single person living with disability in its CC. Nor do any of the major parties have members representing the LGBTIQA+ community.

Unlike the Maoist and the UML, the Nepali Congress held elections for the party’s Central Working Committee and the candidacies contending for leadership were in consonance with the clusters. But the inclusion of privileged candidates like Arzu Deuba from the women’s quota, Binod Chaudhary from the Madhesi quota, and Umesh Shrestha from Janajati quota came to be widely criticized.

The conventions also brought many political couples to the respective central committees, which was essentially a triumph of nepotism over inclusion. Reservations and quotas are clearly meant to lift the marginalized groups, not for the elevation of the already dominant groups.

According to the constitution, women are marginalized on a gender basis, Madhesis and Janajatis on a cultural basis, Dalit on a caste basis, and remote areas on a geographical basis, and inclusion should be made proportional to their respective population shares. Therefore, UML should have had at least 100 Janajati members in the CC, as Janajati are 36 percent of Nepal’s population—but that is not the case. All the major parties are led by Khas-Arya males who seem to see inclusion as a danger to their traditional hold over power.

Political elites continue to be exclusionary

Tula Narayan Shah

Political analyst

Even after various political movements in Nepal that championed the agenda of inclusion, things have not changed much. During the Panchayat period, Chhetris used to be political party leaders and Brahmins their advisors, now Brahmins are the leaders with Chhetris are right behind them. The tendency is not to recognize leaders from the marginalized groups as national leaders.

Nepal adopted the inclusion policy by relying on the Interim Constitution 2007, which provided for reservation in the bureaucracy, increased electoral constituencies and revised the election process. Yet the state is yet to take ownership of these agenda. Unless the elite class becomes more accommodative, change is difficult, as demonstrated by the recent party conventions. What happened was, basically, those in power used inclusion principles to cement their own hold.