Hom Nath Bhattarai, spokesperson of Sajha Publications, the oldest publishing house in Nepal, is of the view that Nepali literature isn’t as deep and meaningful as it used to be during the time of Laxmi Prasad Devkota or Parijat. This, he says, could be because readers today prefer entertainment over introspection and publishing houses have had to cater to that. However, the strategy hasn’t really worked in the Nepali market—there still aren’t many people reading Nepali books, at least not enough to make publishing a viable business or for Nepal’s literature scene to flourish.

“There was a time when books had social messages. They were lesson- and value-oriented. The audience was mostly academics and those who believed reading was crucial for intellectual growth,” says Bhattarai. Generally, youths in Nepal weren’t reading much back then. Bhattarai believes Narayan Wagle’s ‘Palpasa Café’, a story about an artist during the civil war in Nepal, published in 2005, changed that. It was what got Nepali youths interested in Nepali novels. Palpasa Café had a simple, moving premise and characters youths could relate to. After that, the publishing industry saw a surge of authors telling relatable stories, trying to pull in that crowd.

Chandra Siwakoti of Pairavi Book House agrees that there was a phase when youth-centric and love stories by Buddhi Sagar, Amar Neupane, and Subin Bhattarai, to name a few, made youngsters gravitate to reading. But social media soon took over and that trend quickly died. The Nepali publishing industry is struggling today as the market is small and there are, he says, far too many writers. “During the Covid-19 lockdowns, everyone was writing something or the other because suddenly they had all that free time,” says Siwakoti. “We got so many submissions in the months that followed.”

However, Bhattarai and Siwakoti both believe quality writing is hard to come by, and that publishing houses today have had to compromise on quality to survive. Bhattarai also laments the new trend of self-publishing. He doesn’t think these self-published books will add value to our literary scene because without proper editors and publishers working on multiple drafts of a book, a writer can only bring so much nuance into the work. “As a writer you can’t be critical of your work. That’s why self-published titles are often rough drafts of what could have been good books,” he says.

Also read: Fixing Kathmandu’s chaotic roads

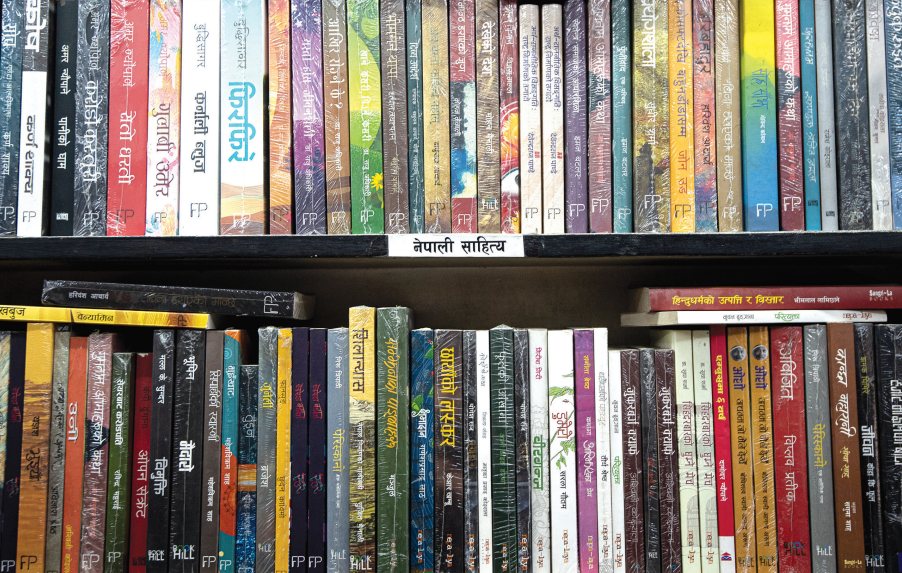

Bringing out a good book requires the expertise and effort of many people, says Bhattarai. So, it helps if new and even experienced writers have the backing of a publishing house. Bhattarai says the publishing house FinePrint has been trying to promote—and to an extent succeeded in promoting—new writers and Nepali literature. He says it seems to have new ideas on how publishing can become a profitable business. From introducing lightweight paper to publishing a wide range of books, FinePrint has been at the forefront of the publishing industry—trying out new tricks of the trade to sustain the book business.

Ajit Baral, co-founder of FinePrint, says their focus is on good editing, design, and layout. He, along with Niraj Bhari, started FinePrint because he was passionate about reading and writing. They didn’t think of it as a business. It was what earned them a good name and trust among readers and writers alike. That, in a way, has also helped them persevere when things have been rough like during the Covid-19 pandemic when work came to an absolute halt. Baral says they are still trying to recover from the setback. “It’s only a matter of time, I hope,” he says.

Not just FinePrint. Things are far from easy for everyone involved in the publishing business. Chiran Ghimire, manager at Himal Books, says it sometimes takes a year to sell even 1,000 copies of a really good work. This he attributes, in part, to people reading more on digital platforms as opposed to buying physical copies of books, which can be expensive. But the main reason is that people’s aptitude for reading has been on a decline for quite a while. Siwakoti of Pairavi Book House says it has been steadily dwindling in the past seven years. Pairavi has been sustaining itself by focusing more on publishing legal books which, being compulsory reading for many, has a solid market. “We haven’t been publishing a lot of literary works as Nepalis aren’t reading all that much,” says Siwakoti.

When a new Nepali book comes out, there is generally a lot of buzz on social media. But that doesn’t necessarily lead to a spike in sales, say those in the industry. Kalpana Dhakal, CEO of Kitab Publishers, says there was a time when reading and publishing were at their peak. When Sudhir Sharma’s ‘Prayogshala’ and Hari Bansa Acharya’s ‘China Harayeko Manchhe’ were published in 2013, they were well received and did good business as the market was booming. That, she says, isn’t the case anymore.

Also read: Misogyny in Nepal: Little acts, big consequences

In the course of doing market surveys before the launch of her company Dhakal spoke to various booksellers who confessed they didn’t sell as many copies of Nepali books as they did before. Even the classics, for instance books by BP Koirala and Parijat, aren’t in much demand. Books written in English on the other hand, they said, did relatively better. “I’m new in this business so I try to find out how others are doing. Everyone in the publishing industry seems to be on the same boat. We are all barely sustaining ourselves,” says Dhakal. She feels unemployment (hence no compulsion to read and learn) and a variety of entertainment options are the main reasons why reading isn’t a culture in Nepal and that doesn’t give her the confidence to publish more than two to three books a year. It just isn’t a wise business move. But Dhakal is hopeful of a brighter future because societies need to grow and for that reading and writing are essential.

Bibash Shrestha, sales officer at Kathalaya, says there is a need to explore different ways to make reading an inescapable part of people’s lives if the publishing industry is to thrive. With that in mind, Kathalaya did workshops and community-level literature festivals in the past. They also translated different language books into Nepali to expose people to a wide array of authors and works. Publishing houses, he says, should do a lot more than publish books to make theirs a viable business.

Writer and historian Sujit Mainali adds that the only goal shouldn’t be to come out with bestsellers. It’s important for authors to write on topics they are well versed in. Bhattarai says some books, despite not having mass appeal, are important to document the culture and history of a community or a place, and these books need to be published even if they aren’t commercially viable.

Baral, on the other hand, sees the need to tap into the e-book market. The problem, he says, is that individual publishing houses don’t have the resources to invest in something that won’t give immediate returns. Those in the business agree that collaborative efforts could also be a way forward. Siwakoti says publishers could start by having more discourses to figure out what kind of writing they should promote and how to do that. “We are responsible for creating and maintaining the quality of Nepali literature and it’s time we took that seriously,” he says.