Not many people get to see the newspapers from the day they were born. When I got the chance to see the edition I wanted, I was both amused and intrigued.

As I sifted through the hard-bound collection of old newspapers, I found it. The edition of Gorkhapatra did look a little different from papers today. Once I read the headlines, I was hauled into a different time. Some 30,000 houses in the rural east had just got electricity, a bus service was shut down in Rautahat after one of its buses splashed some mud on a pedestrian with the driver being seriously beaten up by villagers, an ordinance regarding animal service was being discussed and Girija Prasad Koirala was the prime minister.

Even more exciting was stumbling upon a copy from 19 March 1955, with the front page detailing the last rites of the just deceased King Tribhuvan (pictured alongside). How did it feel? Surreal, almost like I had hopped on a time-machine.

There were rows of Gorkhapatra and The Rising Nepal archived at Gorkhapatra Sansthan. The institution, located at New Road, is the publishing house for these dailies and other widely read magazines like Madhurparka, Muna, and Yuvamanch.

As I spent time at the archive, leafing through much older editions, it was evident that I was amid a trove of invaluable resources. Bimala Khadka, the head of the archive section, informed me that the library is usually frequented by journalists, researchers, students, and government officials. “The place is usually filled, or at least it was before the pandemic. The pandemic has affected footfall,” she mentions.

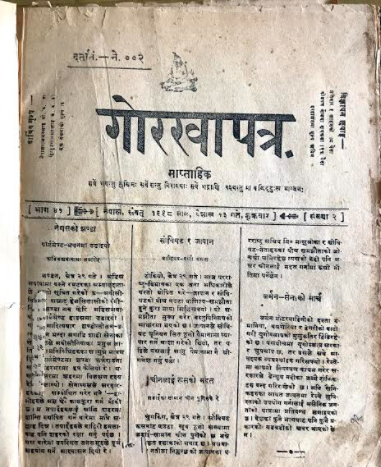

We’re used to viewing colorful, ad-laden articles today, mostly on screens. Navigating Gorkhapatra pages from more than a hundred years ago is in no way comparable. The fonts on these pages aren’t easy to discern, the parlance is archaic, and there aren’t many parallels you can draw to the world around you today. This perplexity is accompanied by the looming reminder that you cannot be too careful turning the pages that have and will outlive you. There are perhaps few to no other resources that reflect the times of the yesteryears like these papers do.

Gorkhapatra frontpage, 25 April 1941

Ramesh Parajuli, a researcher who frequents the archives to learn more about the past, says, “The older editions are essential to learning about the governments’ decisions and actions.” Since its inception in 1901, the institution has been owned and operated by the government. Being a state-run media house, it has chronicled governmental pursuits. Parajuli says that accessing such news pieces helps in triangulation and verification.

With such extensive resources at its disposal, Gorkhapatra Corporation is also aiming to diversify its audiences and make its resources more easily accessible by digitizing the archives. This would make accessing information streamlined. Gorkhapatra already has an impressive following online. According to Shiva Kumar Bhattarai, acting general manager of Gorkhapatra Sansthan, the online site currently receives more than 700,000 daily visitors. Having the archives digitized would make information much more easily available. The digitization has been in the works for the last three years and is expected to be completed soon. Until then researchers will have to use physical copies or view microfilms.

An indispensable legacy

Gorkhapatra is the oldest national daily of Nepal. It was launched as a weekly in 1901 and became a daily 60 years later. It is currently the sixth oldest newspaper in South Asia.

This age is reflected well on the archived papers as time has colored them yellow. I remarked about this and learned that it was not only because of age but also that at one point, to make Gorkhapatra look cleaner, the whiter paper started being used. Catering to as many Nepalis as possible, Gorkhapatra is also printed in Kohalpur and Biratnagar, as compared to just Kathmandu in its early days, with a total circulation of more than 50,000, in addition to its many online visitors.

According to Gorkhapatra’s acting GM Bhattarai, even though the institution is government-owned, it is always attempting to report credible and factual news that serves the public. “Gorkhapatra is the voice of the public and is trustworthy. We always publish factual and authentic news.”

In a way, this conveys that there is an awareness of Gorkhapatra’s position as a state-owned media house.

Researchers like Parajuli are aware of how in the past, the institution’s position has had a bearing in its reporting. Gorkhapatra has been scrutinized and criticized for being the governments’ proponent. For example, Gorkhapatra did not report the execution of the martyrs of Praja Parishad in 1941. Parajuli also mentioned that more recently it has relegated news of the opposition to smaller spaces on the paper.

Bhattarai's avowal to factual and unbiased reporting should be taken as a sign of hope following these blips in the paper’s past, however, not without a probing eye. The legacy of Gorkhapatra lives not only through its publications and archives but also through many senior Nepali journalists who have at some point in their careers been affiliated with the institution.

Gorkhapatra’s contribution to Nepali media and history is prolific. Its publications have promoted journalism and literature for more than a century and continue to do so in an age where there’s stiff competition from other, private companies and other forms of media. Its archive is pivotal for research about Nepali social and political history. Gorkhapatra’s legacy is thus, undeniable and one that deserves great acknowledgment.