The lockdowns amidst Covid-19 pandemic had the world hoarding toilet paper. Many families now probably have enough to last at least a couple of years, if not a decade. Apparently, quite a few avid readers in Nepal bought books just as frantically. Those in the book business say many Nepalis seem more inclined to read today than ever before.

“There was a time when only tourists would buy books. Bookstores didn’t appeal or cater to Nepalis,” says Daya Ram Dangol, owner of Book Paradise in Jamal, Kathmandu.

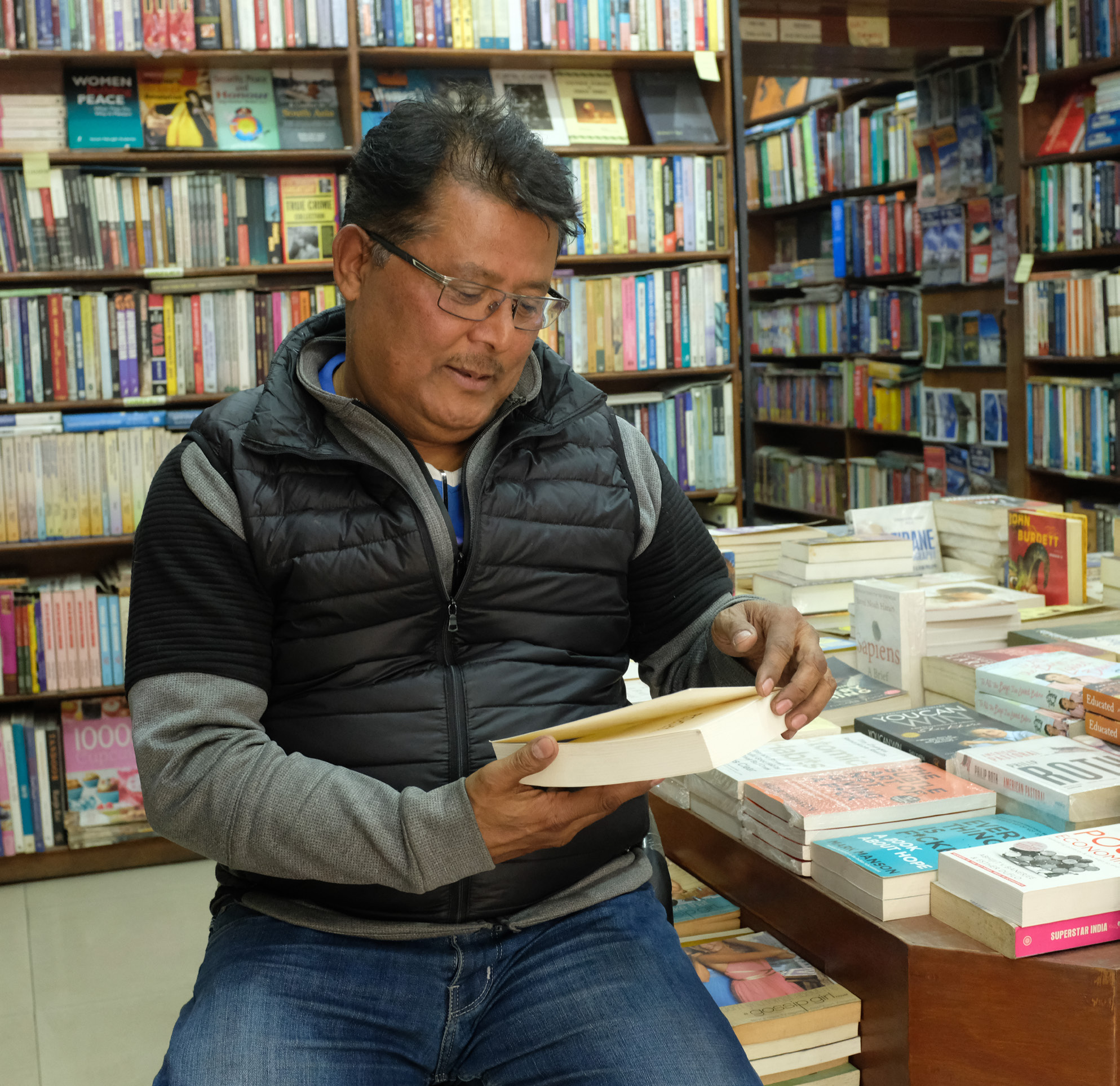

Daya Ram Dangol, owner of Book Paradise in Jamal, Kathmandu

Daya Ram Dangol, owner of Book Paradise in Jamal, Kathmandu

Dangol has been in the book business for over 45 years. When he started, he says, the bookstore he worked at only sold travel books—mostly on Tibet, Bhutan, India—photo books, and a select few coffee-table books.

Things, he says, have definitely come a long way with over 95 percent of his customers today being young Nepalis who, according to Dangol, have varied interests.

“I rarely get foreign customers today. There was a time when the entire business depended on them,” he adds.

He feels this change in the reading scene in Nepal can, to a large extent, be credited to the internet. People these days know about new releases in the market. It isn’t like before when you would have to go to a bookstore to find out what was available.

Siddhartha Maharjan, manager at Mandala Book Point in Kantipath, Kathmandu, highlights the media’s role in making books popular and reading trendy in recent times.

“A lot is being written in the print media about literature these days and that gives books and authors the visibility they deserve,” he says.

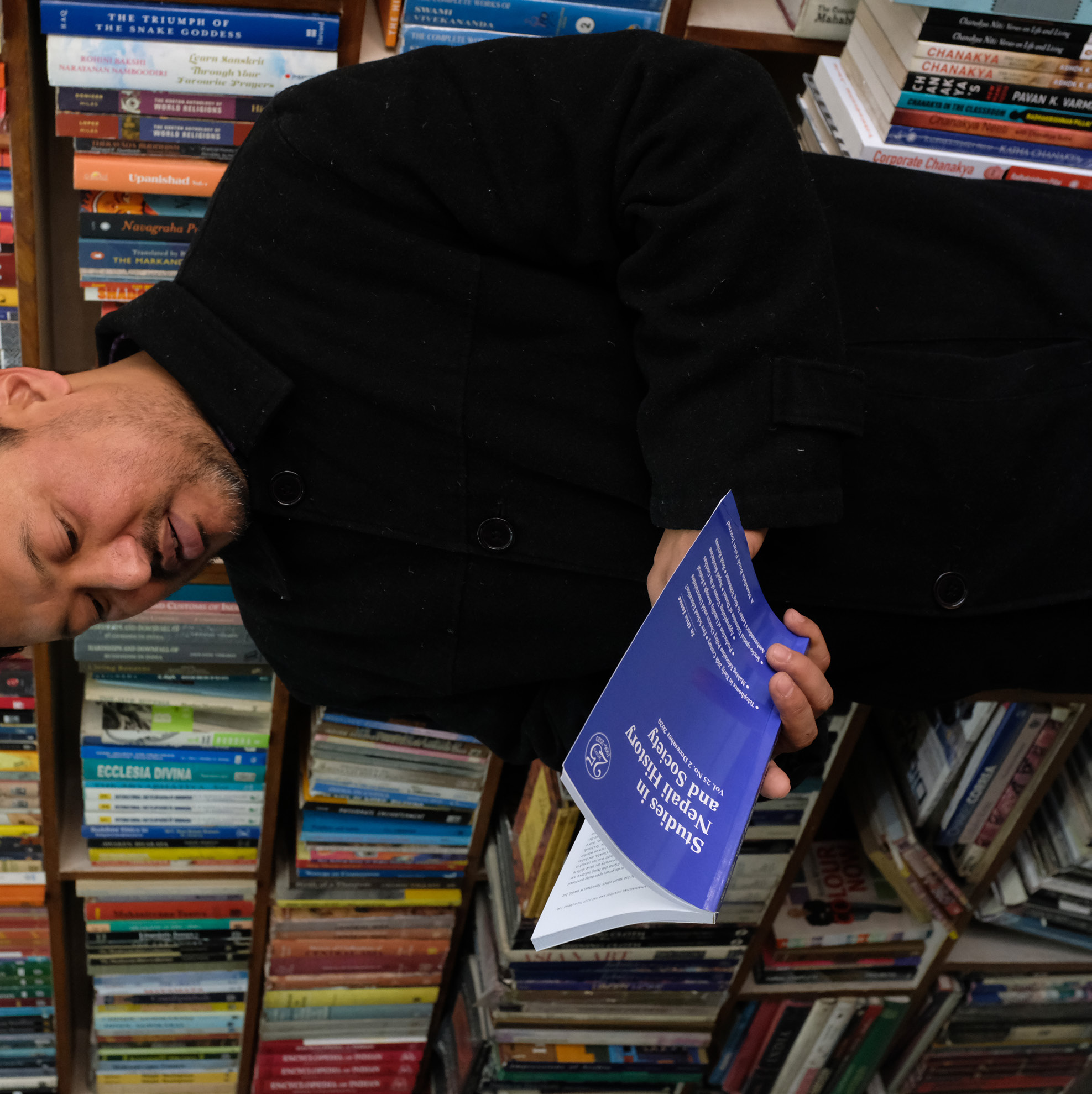

Siddhartha Maharjan, manager of Mandala Book Point, Kantipath, Kathmandu

Siddhartha Maharjan, manager of Mandala Book Point, Kantipath, Kathmandu

Maharjan, however, says that Nepal doesn’t have a thriving reading culture—not yet. Most people, he says, read just the bestsellers or books that come highly recommended, be it by friends or on social media.

Like most good habits, a reading habit isn’t something that can be cultivated overnight. And like most habits, the earlier you start reading the better, says Maharjan.

In this regard, schools can and have been playing an important role by giving children reading assignments. But most parents themselves buy the prescribed books for their children—on their way to work or back home. According to Maharjan, there aren’t many parents who actually bring their children to the bookstore and let them pick books.

“This concept of letting kids explore a bookstore is missing here in Nepal and that is what is hindering the development of a reading culture,” he says. Only when children go to bookstores to find a particular book and then come across something else they like, Maharjan adds, will they eventually start reading on their own—not because they have to, but because they want to.

Radha Sharma Rai, senior sales manager at Ekta Books, says they have a rather large children’s section with a kid-friendly setting at their bookstore in Thapathali, Kathmandu. The intent is to get parents to let their kids roam around and discover books. She says she sees many people, who themselves grew up reading, bringing their children and letting them choose books on their own.

Besides cultivating a lifelong reading habit, bookstore owners APEX talked to said that Nepalis, in general, are definitely reading more than ever before—even if it’s a one-off popular book or pop-fiction by Paolo Coelho, Nicholas Sparks, and Chetan Bhagat.

While the older generation seems to prefer books on politics and economy, young Nepalis, they say, are mostly reading about personal development, businesses and startups, and spirituality. But the one genre that apparently sells across ages and interests is biography. With every other celebrity and politician talking about their lives, there is always some book selling like hotcakes.

The Covid-19 pandemic didn’t harm the book business. Rather, as bookstores took to Instagram and other social media platforms to showcase what they had in stock, their businesses actually did quite well. Granted, they had to tweak their business modules a bit but things have pretty much worked to their advantage.

“People these days want to know things. They want to be better versions of themselves. They want to develop new skills. And they realize reading books on topics they are interested in is a great way to do all that,” says Dhan Bahadur Lamsal, proprietor of Fewa Book Shop in Lakeside, Pokhara.

Pratima Sharma, who looks after online sales and marketing at Nepal Mandala Book Shop, also in Lakeside, says people turn to books looking for solutions to issues they might have. And it helps that we now have access to a variety of books, she says.

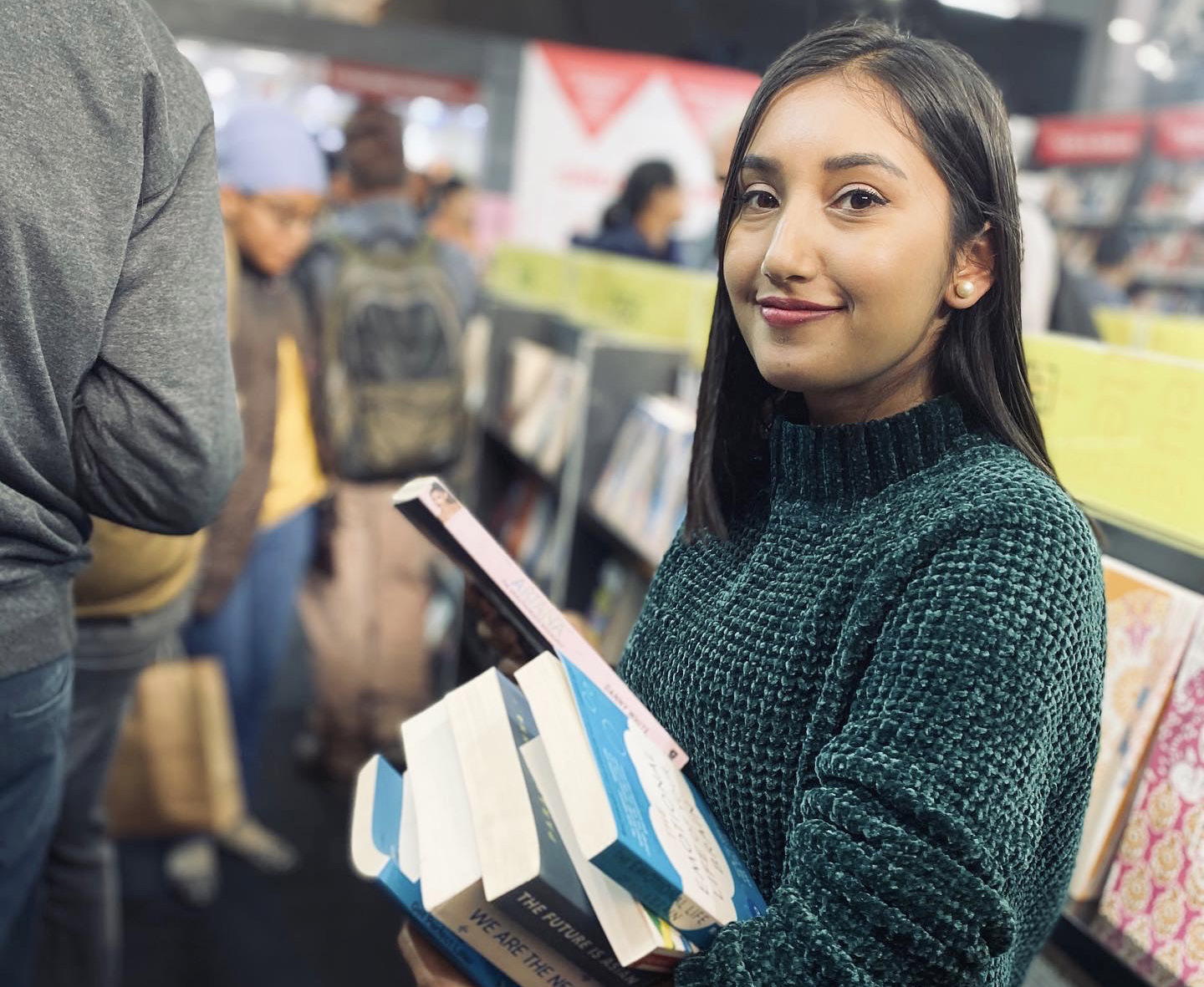

Pratima Sharma, online sales and marketing officer, Nepal Mandala Book Shop, Lakeside, Pokhara

Pratima Sharma, online sales and marketing officer, Nepal Mandala Book Shop, Lakeside, Pokhara

“I see a lot of people gravitate towards recent releases, poetry, and self-help,” says Sharma, adding that there seems to be a keener interest in books today as compared to, say, even five years ago.

But ours isn’t a conducive environment for promoting a reading culture, she laments. Books, she says, don’t come cheap. An avid reader herself, she confesses she probably wouldn’t have had access to or been able to afford many books if her parents didn’t own a bookstore.

Nor do we have good libraries in Nepal. This, Sharma says, not only increases piracy but also makes people search for other, cheaper or free, means of information and entertainment.

“The few libraries that we do have, have old books that are usually falling apart. Unlike in other countries where libraries get plenty of copies of new releases, libraries here run mostly on donated books,” she says.

If every Nepali city were to have at least one well-equipped library then that would mean even those without the means to buy books could take to reading. Sharma thinks the government should look into this. After all, in the long run, a robust reading culture helps create a society of smart individuals which could in turn foster prosperity and development.

There is also no concept of sharing books among readers in the community in Nepal. In many parts of the world, Little Free Library, a non-profit based in the United States, promotes neighborhood book exchanges. The aim is to increase access to books for readers of all ages and backgrounds. Communities here could also work upon a similar idea to get more people reading.

For now, Dangol at Book Paradise thinks easing the import process and not levying heavy taxes on books could help in making books accessible to all. Lamsal of Fewa Book Shop agrees. These days our education system supports free thinking and forming opinions from early on. This, he says, naturally has people wanting to read more. Hence, the only caveat to fostering a reading culture is making sure people who want to read have the resources to do so.