Ghana Shyam Gurung: The champion for snow leopards

Quick facts

Born on 17 June 1965 in Upper Mustang

Went to Janahit Secondary School, Mustang

Graduated from Lincoln University, New Zealand

Got a PhD in Natural Science from University of Zurich, Switzerland

Started working in 1986 from the Annapurna Conservation Area

Husband of Anita Lama Gurung

Father to Mendhala Lama Gurung

I come from a small village called Dhee in Upper Mustang where most villagers in my time were into cash crops and livestock. As I belonged to a herding clan, my summers were spent tending to sheep, goats and yaks. In the winter, I used to go down to Tatopani in Myagdi district, a business hub at the time, with my father and grandfather to exchange our salt for rice and other products.

My early education began at the local Buddhist retreat center, where my uncle, the head monk, taught me to read and write ancient Tibetan text. After spending four years with my uncle, my grandfather, who was fluent in Tibetan and Nepali, insisted that I go to a proper school and get a regular education. I started formal education at 10 and was a decent student—both in monastery and school. My family had to sell a goat or a sheep every month to fund my studies in Jomsom, and I’ll always be grateful to my family for giving me the opportunity to study.

There was no SLC exam center in my area at the time and I had to walk for 11 straight days to get to Pokhara to give the school-ending test. Even in Mustang, the kids from my village were called pakhey (a derogatory term used to describe someone who is ignorant). You can only imagine the treatment we got in Pokhara. The biggest challenge for me was to learn English, so I bought three guidebooks and memorized their contents by rote for my SLC exams. It was a huge deal when I passed the test as I then became only the second person from my region to graduate with a first division.

I then came to Kathmandu for further studies. Imagine someone from the rural mountains looking for rented rooms in the national capital! My struggle began from the moment I got here. I knew it would take a lot of work to catch up with the other students at Amrit Science College, but my tough upbringing had prepared me to cope with all of life’s challenges.

Mingma Norbu Sherpa, who established WWF in Nepal, was to play a crucial role in my academic endeavors. He asked me if I wanted to study abroad and I said yes. He along with Sir Edmund Hillary interviewed me. Hillary asked me to sharpen my language skills, while Sherpa asked me to list out ways to conserve snow leopards. I told Hillary that I could master the language, but to give an informed answer to Sherpa, I still had a long way to go and a lot to learn, despite having grown up amid snow leopards.

I had been raised in a herding community and deep down I always wanted to kill snow leopards that used to prey on our family livestock, killing seven, eight, and sometimes even 10 of them in one hunt. Luckily, I got accepted at Lincoln University in New Zealand and there I got to view animals such as snow leopards from a completely new angle. The more I understood the part they played in maintaining the delicate balance of ecosystems, the more I felt the urgency to protect them.

Ghana Shyam Gurung following snow-leopard tracks at Khampachen Ghunsa of Kanchenjunga Conservation Area in 2012 | WWF Nepal

After my graduation, I returned to Nepal and started working in Annapurna Conservation Area in 1993. Until that time, there was no concept of community-based conservation and eco-tourism. The locals were also left out of the nascent tourism industry. Realizing the need to ensure community leadership in conservation, I started eco-tourism practices, which involved responsible travel to natural areas, conserving the environment, and improving people’s well-being.

At first, the locals didn’t understand the concept and I became a subject of their aggression. However, with time, I was able to persuade them to look at snow leopard conservation in a different light. This was done by talking to them about the benefits of eco-tourism to their livelihoods and the environment, which eventually helped me gain their trust and support. I knew that snow leopards could not be saved without safeguarding the livestock of the locals.

Without a community-based approach, we simply can’t conserve wildlife. Like the way I used to hate snow leopards in my childhood, villagers used traps and poisons to kill them. It was the same story in many parts of the snow leopard range in Asia’s High Mountains—herding communities killing snow leopards in retaliation for attacks on their livestock. This conflict was one big reason for the decline in their numbers.

But I believed that if there was a community-based insurance scheme for their livestock, the locals could be persuaded to be active partners in conservation efforts. With this in mind, I joined WWF Nepal in 1998 and started programs on community-based snow leopard conservation with livestock insurance in the Kanchenjunga Conservation Area in 2004. This pioneering work soon became a milestone in Nepal’s conservation movement. For that, I have been recognized by many international forums and recently, the president of Nepal conferred me with the conservationist medal, Prabal Janasewa Shree Chaturtha.

The initiative compensated herders for any livestock that they lost to snow leopards, providing them with the financial support they needed to cope with their losses and a reason not to kill the endangered animal. After working closely with them, the communities eventually took ownership of the efforts to protect snow leopards, especially after they were taught ways to prevent snow leopards from attacking their livestock and provided compensation when they did lose livestock. All these efforts to protect the snow leopards have vindicated my decades of effort and completed my transformation from a herder to a conservationist.

About him

Mendhala Lama Gurung (Daughter)

From a humble start in the foothills of Mustang to being one of Nepal’s leading conservationists, my father has relentlessly worked to conserve Nepal’s biodiversity for the past 35 years and continues to do so with the same passion. He is a role model for aspiring conservationists and environmentalists alike, and I am confident he will continue to inspire others with his brilliant work.

Shant Raj Jnawali (Friend/colleague)

With his decades of experience, Ghana Shyam Gurung has contributed a lot to wildlife conservation and has represented Nepal in many international forums. Regarded as ‘Snow Leopard Champion’ for WWF Network and Himchituwako Gothalo, he is enlisted by the World Atlas among the ‘12 incredible conservation heroes saving our wildlife from extinction’. His work continues to inspire his colleagues and friends alike.

Rinzin Phunjok Lama (Mentee)

I have known Gurung since 2007. He has been a source of inspiration for many young university graduates in the field of conservation. I am following in his footsteps to become a good conservation leader myself. I am particularly inspired by his simplicity, humility, power to motivate youths, and deep passion for nature conservation.

A shorter version of this profile was published in the print edition of The Annapurna Express on July 7.

Basant Raj Mishra: A global ambassador of Nepali tourism

Quick facts

Born in Feb 1953 in Kathmandu

Went to Padmodaya School, Kathmandu

Graduated from Patan Campus, Lalitpur

Started the Temple Tiger Group of Companies

Husband of Jyanu Mishra

Father to Brajesh Raj Mishra

I was born into a family with a bureaucratic background, but a government job never appealed to me. My interest was rather in business, to start something of my own. So I traveled to Europe after my graduation and took many short-term courses in business management, marketing and public speaking.

Europe taught me that work is vital, not just for income but also to establish your identity. Ultimately, what matters is not how much you earn but who you are.

In 1977, I started my career in tourism. After working as an apprentice in a few companies for some years, I started a few ventures of my own in partnership with other like-minded people. Temple Tiger Group of Companies was established 11 years after I started out in tourism. The idea was to promote sustainable and responsible tourism in Nepal and we were among the first companies to do so.

Nepal’s tourism industry formally started in the 1950s after Mountaineer Maurice Herzog led a French expedition to the Annapurna in 1950. They were the first team to successfully climb a peak over 8,000 meters. Three years later, in 1953, Tenzing Norgay and Edmund Hillary would conquer Everest, which made Nepal popular worldwide. Foreigners started coming to Nepal, and Kathmandu and Pokhara became the places from where they would head out to the Everest or Annapurna regions.

The country’s tourism industry was still in its infancy but it didn’t take long to flourish, as tourists began exploring other parts of the country as well.

In the late 70s, mostly, people from well-to-do families and those who could speak and write in English were involved in tourism. I was the perfect person for the job and I enjoyed it a lot. What tied me to this industry were the people I got to meet, which in turn boosted my interpersonal and marketing skills.

When I was starting, many tourists used to visit Nepal through Indian travel agencies which considered Nepal an extension of their own country, which I didn’t like. My goal was to make Nepal a stand-alone destination. I collaborated with many foreigners to make this happen. In those days, I used to be outside the country for almost four months a year, meeting influential people and inviting them to visit Nepal.

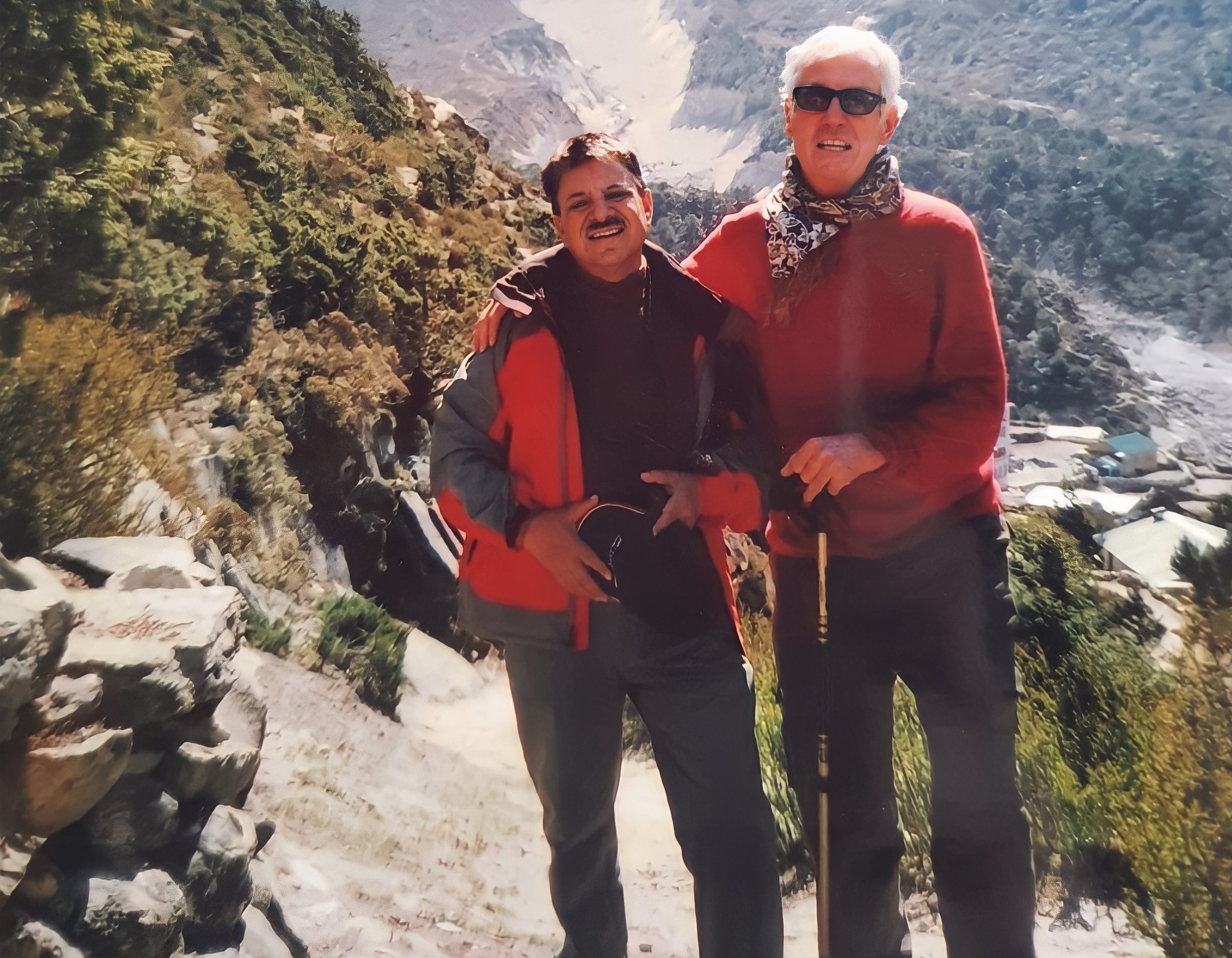

Basant Raj Mishra (left) and Robin Marston, managing director of the first trekking company in Nepal, Mountain Travel, during their Everest Base Camp trek in 2017.

Basant Raj Mishra (left) and Robin Marston, managing director of the first trekking company in Nepal, Mountain Travel, during their Everest Base Camp trek in 2017.

I also joined numerous national and international tourism organizations to promote Nepal.

India was positive about our move and we worked together and exchanged tourists on several occasions. We organized combined cultural tours and both countries benefited. I have brought many international journalists, who were originally on an India visit, to Nepal in order to promote the country as a tourism destination.

These days Nepal and India lack the kind of coordination on tourism that we once had.

I was also the first person to introduce the concept of tour escort in Nepal. Tour escorts were with tourist groups throughout their trip. I was the one to train five fine Nepali guides and send them with tourist groups as tour escorts for the first time. Nowadays, all the tour escorts are Nepalis.

Shifting to conservation tourism was my best career decision. In light of the prevalent climate change, Nepal has always been at the forefront of travel practices that minimize environmental waste, encourage conservation and educate travelers on the environment. Nepal is a pioneer in conservation, adventure and wildlife tourism. When it comes to wildlife tourism, Nepal is the Africa of South Asia.

I have overcome many odds to succeed in this sector. There are new setbacks and challenges every other day, but I can deal with them as I am a very adaptable creature.

For example, at one time, our investments in conservation tourism sank as hotels inside national parks were closed down. It was a profitable but labor-intensive and fragile business. We learned from that experience and moved on.

The Nepal Tourism Board was formed in 1998 to get the private and public sectors working together in tourism promotion. I was appointed the founding director of its board, which in its early years became a global example of successful private-public partnership.

But things have not been going well of late as the government these days does not seem keen on private-public partnerships. The Tourism Ministry has monopolized the board’s functioning.

Nepal is still a great tourist destination but we have to improve a few things. We need to develop our infrastructure and invest in marketing to put Nepal on the global tourism map. The other area of improvement is aviation. Tourism and aviation are the two sides of a coin. In the end, we have to understand that tourism could single-handedly take care of Nepal’s economy. All we need is the right approach.

About him

Pius Raj Mishra (Nephew)

Basant uncle lives by the mantra: ‘work is worship’. Hard work has given him global recognition of a successful tourism entrepreneur and conservationist. He believes in a welfare-oriented society and helps people in need. Even in our own family, everyone rushes to him for help and advice. I retired at 65 but he is still working with great energy at 70. Kudos to him!

Capt Rameshwar Thapa (Friend)

Basant Raj Mishra is a gift for Nepal. He is the kingpin of Nepal’s tourism industry, especially of wildlife and conservation tourism. Many international organizations have recognized his works and he has been able to promote Nepali tourism through numerous international seminars and conferences he has attended. Mishra is like a family member to his friends and colleagues. He is helpful and always ready with innovative ideas.

Sanjay Nepal (Colleague)

Basant Raj Mishra gave me the chance to travel to Tibet and other parts of the world as a tour guide. In tourism, many people are double-tongued but he is what he is. If he is angry, he will show it to you. He is also open-minded, a quality that many lack. Most importantly, he is a determined learner. To this day, he calls me for suggestions. An owner of a well-established company, he doesn’t have to do that—but he does.

A shorter version of this profile was published in the print edition of The Annapurna Express on June 30.

Ram Kumar Panday: Not enough hats for the ace geographer

Quick facts

Born on 9 July 1946 in Lalitpur

Went to Patan High School, Lalitpur

Graduate from Patan College, post-grad from Tribhuvan University

Completed the pioneering ‘Special Distribution of Settlements in the Mountains of Nepal’ research in 1980

Husband of Amita Panday

Father to Tethys Panday and Pangaea Panday

I had an educated family who constantly supported and encouraged all my education endeavors. I was fortunate, in that not everyone was allowed to go to school while I was growing up. I was a decent student who loved reading books and learning about new things. Arts and literature were my particular interests.

After completing my intermediate (equivalent to today’s high school degree) education, I wanted to study literature. I was already writing poems, essays and stories. But I decided to study geography. I realized that I could read and learn about literature on my own and that I needed to tackle something I didn’t know much about, something out of my comfort zone.

I got my master’s degree in geography in 1970, but I was not content with it. I felt like many things were missing in the curriculum. I then decided to pursue another degree; and this time I chose sociology as I wanted to know more about Nepali society.

I joined the Tribhuvan University as an assistant lecturer in geography in 1972, became a full-time lecturer in 1979, and a reader (principal lecturer) in 1988.

I was promoted to the post of professor in 1993, so I have served at the university for almost four decades. During my time at the university, I visited various parts of Nepal for research, which I found both enjoyable and intellectually rewarding. Everywhere I went, there were new things to learn.

For instance, in one of my research tours, I discovered that there were many variations of nature between the altitudes of 58 meters and 8,848 meters.

In 1980, I did research on ‘Special Distribution of Settlements in the Mountains of Nepal’, and found that 60 percent of the country’s settlements were between the altitudes of 1,000 meters and 1,500 meters. This paved the way for more studies, such as the ones on finding scientific reasons for this.

This was the beginning of my study on ‘altitude geography’ in Nepal. This was something unique not just for Nepali professors, but also for international scholars.

Ram Kumar Panday speaking at the launch of his book ‘Nepalko Uchai Bhugol’ in 1987.

Ram Kumar Panday speaking at the launch of his book ‘Nepalko Uchai Bhugol’ in 1987.

The climate of Nepal is always referred to as ‘Mountain Climate’, but this is wrong. Different places here have different types of climates and vegetation.

For example, apples grow in the mountains while bananas ripen in the Tarai on the same day. Where else on earth does this happen? If you tell this to a Bangladeshi, he will not believe you, as Bangladesh doesn’t even have a hill as high as 200 meters. I believe we cannot develop Nepal without understanding our altitude geography.

We lap up what foreigners say about Nepal and seldom draw our own conclusions through rigorous study and observation. And even if someone tries to carry out a research, policy and curriculum developers rarely encourage them. For example, senior professors made fun of me when I shared my findings on altitude geography. You see, I was not a foreign scholar.

Even foreign geographers like Toni Hagen have praised my five books on altitude geography. After seeing my work, the Swiss geographer even went so far as to say that Nepal doesn’t need international geographers. It was this praise from Hagen that made my seniors and fellow colleagues acknowledge my findings.

Each country has a specialty course in their universities. I had proposed starting a course on altitude geography and thereby attracting students from around the world. But my seniors didn’t approve of this idea. Doing so would perhaps have been humiliating for them as it was their junior who had come up with a new curriculum idea.

Our academia is conservative and there is a constant clash of egos.

I strongly believe every Nepali should know about their country. I had written the book, ‘Nepal Parichaya’, which was taught at the +2 level. I had put a lot of effort into the book, to help those who wanted to understand Nepal. One fine day, the book was removed from the curriculum and I still don’t know why. I also wrote ‘Biswo Parichaya’ and although this book wasn’t intended for college students, graduate students should still read it to know about the world.

I have also written three volumes on Yeti, the Himalayan snowman. The books were born out of an incident, whereby a foreigner was trying to find a good book about Yeti but couldn’t. In order to satisfy the need of this foreigner, I personally set out to find a definitive book on Yeti, only to discover how little had been written about the mythical creature. So I ventured to write a book on Yeti on my own. It did well, particularly among foreigners.

I am also into fine arts, woodcut prints, humor writing, fiction writing for children and young adults, poetry, and philosophy. I serve as the president of the Center for Nepali Geography, Humor and Satire Society Nepal, Nepal Haiku Center, PEN International Nepal Chapter, etc. My professional and personal pursuits keep me occupied.

About him

Amita Panday (Spouse)

He is a fine painter and a woodcut artist. I also do arts—all inspired by him. He is also considered a proponent of the Haiku (Japanese format poem) movement in Nepal. He has published over 100 books in English and Nepali, and is working on many more. I am so proud that he has represented Nepal on various international platforms. He is an inspiration.

Mitra Bandhu Poudel (Friend)

Ram Kumar dai is a man of many talents, and a true multi-disciplinarian. Every year in Kukur Tihar, he invites writers to his home where he hosts a program on humor and satire. He is a leading figure in many fields. But most importantly, he is a great teacher and always eager to help others learn. He is a scholar set on a mission to promote critical thinking and creative work.

Prakash A Raj (Colleague)

When Ram Kumar Panday was the president of the PEN International Nepal Chapter, I was the general secretary. While at PEN, he did a couple of research on youth literature and realized that youths had no books fitting their age groups. He formed a committee with five literary figures and launched a program on story therapy for principals of different schools, so that they could help students on the right track. He is a born teacher and a leader for whom sharing knowledge is very important.

A shorter version of this profile was published in the print edition of The Annapurna Express on June 23.

Mallika Shakya: The daughter who found her own feet

Quick facts

Born in August 1973 in Kathmandu

Went to Lalitpur Madhyamik Vidhyalaya, Lalitpur

Graduate of Padma Kanya College, Kathmandu, post-graduate of University of Glasgow, Scotland

PhD from London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE), England

Mother to Abha Shakya

Among my strongest childhood memories is seeing my mother going through a crisis and eventually finding her own feet. Ironically, it was around this time that I began to excel in my studies. School grades aside, I became a voracious consumer of written words, drawn to a virtual world away from my everyday reality. I read everything and anything, emptying the shelves of my school library, friends’ family collections and local book shops. I remember the 1990 regime change almost in terms of my book universe: BP Koirala and Parijat’s works (banned during the Panchayat regime) showed me a different side of being Nepali. That was also when I was considered old enough to join British and Indian libraries in Kathmandu. These opened up a new world for me.

I was still almost a child when I took my first job with Save the Children Fund (UK) and then with UNICEF, two full-time jobs I held while studying for full-time undergraduate degrees. I topped Padma Kanya College both in my IA and BA and won two Mukti Rajeswori medals for the highest scores in economics. For IA, I was also awarded the Aishwarya Vidhya Padak (Queen’s Medal) as the nationwide female topper. For BA, I was awarded the Arjun medal for nationally topping the paper on Nepali language and literature across all faculties in all colleges.

Money-wise, I was not expected to support my family but the idea of “standing on your own feet”, especially as a woman who will not inherit family property, was deeply etched. What started as a source of “pocket money” quickly became a way of life. My workplace became the grounds where I acquired initial research, writing, and problem-solving skills. I had prepared myself well when I went to the University of Glasgow for my Master’s degree. I came back with the class prize.

PhD (with the London School of Economics and Political Science) was a new frontier for me, and it took me a long time to find my voice as a scholar. Amid my writing struggle, I put myself up as a contestant in the World Bank’s YP programme, for which they annually recruit 32 young professionals through a fiercely competitive process of elimination from an applicant pool of over 10,000 exceptional people worldwide. I worked to develop the idea of export competitiveness and industrial clusters in its initial phase which have now become its major area of business.

When I was offered the job in the World Bank, I had said that this was my chance to explore and understand the world better, and I gave myself five years for that. By the fifth year when I became entitled to apply for a two-year sabbatical, I had completed and defended my dissertation at LSE. I joined the University of Oxford and later shifted to South Africa to teach. Then I moved back to my home region with a job at South Asian University, from where I sent in my resignation to the World Bank in Washington DC.

Mallika Shakya (middle) speaking on ‘Poetic Imagining(s) of Southasia: Writing Nations through Sensibilities of Resistance’ at South Asian University in New Delhi.

South Africa is where I found my academic voice and also my peace. It is not always easy to disentangle ourselves from the bureaucracies that chain us to our immediate livelihoods, but we must. This has remained my primary intellectual and personal resolve. At one level, we grow up being shaped by the histories that go way beyond our births, and our legacies—however big or small—will shape the world beyond the span of our mortal lives. At another level, our immediate circles do matter, but we will do well by reminding ourselves that we are members of a bigger macrocosm. That our duties and responsibilities should be defined against this broader temporality and context is my firm belief. For me, anthropology (or sociology) has been about finding ways to look at a given social and economic query through these two lenses.

My book “Death of an Industry” asked why so many workers whose livelihoods depended on the garment industry had absolutely no voice in a country whose state and civil society exaggeratedly claimed itself to be democratic. We have been told time and again that democracy entails accountability and empowers the poor, but during that moment of crisis, Nepal came across as a brutally coercive, rent-seeking state which denied basic dignity to its subaltern citizens. We saw its recurrence again during the coronavirus pandemic. I study this collaboratively, joining hands with medical anthropologists, pharmacologists and microbiologists. I begin to understand that “development” is just a tiny episode within the extended history of (crypto) colonization and civilizational subjugation. We need to be honest about the limits of the foreign aid while thinking about human aspirations to prosper and share.

In joining South Asian University as the only Nepali woman, my efforts have been to look for ways to initiate cross-border conversations and solidarities without being caught in the power games of nation-state-pageanting. What national bureaucracies showcase as “success” or “good citizen” or even a “leader” have almost nothing to do with what ordinary people feel and what their aspirations are. Yet we are conditioned to put the former above the latter. Such coercive imagination of predatory nationhood has been on the rise, especially since the end of the Cold War, which has unleashed a new corporatist wave allowing a new round of elite capture of the nation-states.

I don’t think there is much conversation on this, at least within the social sciences. Increasingly I feel that poetry, fiction and arts are mirrors of our times, and we need to take these seriously as a social archive. In my forthcoming publication, I bring together social scientists and literary scholars from around South Asia to discuss their take on the nation-states they are members of. These conversations are insightfully honest about the traumas and disillusionments imposed by coercive and exclusionary nationhood. I hope conversations like these will help us develop methods through which to question the hegemonic paradigms of nationalism and give voice to disenfranchised citizens living in the margins.

About her

Barbara Harriss-White (Teacher)

By leaving the World Bank, Mallika showed that a life in research and teaching was worth more to her than a high salary. To make the change she joined a team in South Africa which gave her unparalleled experience. Her book results from having treated businesspeople and workers in Nepal seriously and with equal respect. By joining South Asian University, she has reaffirmed her commitment to learning without borders. With Abha she is fulfilled as a mother as well. She is a truly remarkable person!

Keith Hart (Teacher)

Mallika Shakya is loyal to her family, friends and country. She has great personal integrity and wide experience of the world—Britain, US, South Africa, India. Her book, Death of an Industry, is a path-breaking contribution to understanding Nepal. She is a fine teacher. Maybe she worries too much.

Sudhir Shetty (Colleague)

Mallika is among the very few women (or men) from Nepal to have been accepted into the World Bank’s highly-competitive Young Professionals Program. At the Bank, her intellectual contributions focused on deepening and applying concepts around export competitiveness and industrial clusters. Her work at the World Bank and more recently in academia highlight her deep interest in development and her abiding commitment to social inclusion.

A shorter version of this profile was published in the print edition of The Annapurna Express on June 16.