Education for a better world

“Education” the word itself is abstract, so it is hard to define. Also, its definition varies among educated persons or scholars. Thus, is it not an important query to identify it in the view of commoners like us? Is the developed countries' education valued higher than the developing ones? Isn’t education for physical comfort, mental peace, or spiritual pleasure? Bunches of perplexing questions arise in this scientific world when biologists share their sharp ideas that in the eyes of science even an atom is equal to man.

The word “education” in English etymology, as defined in the New World Dictionary, originated from the root word of old French ‘duc’ and Latin ‘dux’ which means leader; and in this root added the prefix ‘e’ means ‘out’ and during middle English period ‘duc or dux’ changed into ‘ducere’ which means ‘to lead, draw, bring’.

After such a formation of the word, the meaning of education is ‘to train, develop the knowledge, skill, mind or character through formal schooling, teaching and training ’. In Sanskrit root, according to Apte, ‘Siksh’ means to wish to learn, to practice, and to gain knowledge. William also writes a similar meaning in his dictionary adding that it means to offer one’s service to others as well.

Education has been defined for ages by different educators in their own way of life. For Socrates, education is the idea of universal validity taken out from the talented minds, whereas for Plato it is the capacity to feel pleasure and pain at the right time in the body and soul of a student enabling one for beauty and perfection. For Aristotle, education is the creation of a sound mind in a sound body to enable enjoyment in perfect happiness, but for Nelson Mandela, education is the most powerful weapon to bring a change in the world.

Further, for Sarvapalli Radhakrishna education is not merely a means of earning a living, nor a nursery of thought or school for citizenship, but to train souls in pursuit of truth and practice of virtue. For a reformer from India, Swami Vivekananda, education is “the manifestation of the divine perfection, already existent in man. Hence, it is described by one’s precise definition. As in the above words, if there is no proper or standard education, any society, country, or even the whole world might deteriorate and grief can fall on the people globally. Thus, I would like to express basic standards of education that can help achieve individual or public contentment of being altruistic persons in the world.

The first norm of education to maintain the basic standard might be happiness in personal and public life. Now, in modern education, one has to individually query whether we are living happily or not. Again, happiness is abstract and is difficult to define specifically. But since we can see the worldwide people and figure out how happy they are and how much happiness they can share in the family, society, and country globally. So, happiness here might be the means to quest in education to make a person free from physical and mental pain or agony that everyone is suffering in the present.

Someone might be affluent but may not have sound health. Or both, one may be healthy or wealthy and again have no internal peace at all. Consequently, so-called educated people may start an ammunition factory to kill brothers and satiate individuals as we can see such events in this world. If the revolts take place against one another for personal gains, education may be worthless or faulty!

Secondly, education may be for creativity. Creation, being free from old grievances and acts of revenge, can be innovative for individual and social welfare. It might pave a new way and can make a person to be free from all the creeds or dogmas practiced traditionally. Modern science may be a means of spreading new genes for prevailing peace and prosperity in societies. Such creation should be for the benevolence of humanity rather than the present malevolent construction of modern technology to intimidate or upset the global people.

Thirdly, education may be the means of responsibility. Each and everyone in proper education should be made responsible in one’s living. Modern education has to prepare each individual accountable to carry one’s own duty aptly. Each one should carry on with one’s duty by oneself without pretending or blaming others. In the family, society, or country, each member must be liable to one’s duty and carry on happily whatever it comes to his/her part. This kind of comprehension has to be realized by education in this scientific world.

Next, education should provide everyone with a peaceful living. No individual should be deprived of internal and external peace in their existence. If there is no peace, there is no healthy development. Each child from the home and student from the beginning of schooling must learn to attain peace for a better humanity. Prevailing peace can enable everyone for innovative creations that can produce all-round development in family, society, country and the world.

The requirement of education is to have cosmological living. Man is social and one must know how to work together among various skilled people. For this, a person must be accountable for having an omniscient view that from the atom to the complete universe is correlated in its existence. Having individual or authentic existence, each thing follows a specific system of combination implicitly being conjoined with the holistic system. Consequently, all walks of people should have this sort of comprehension to have prosperity, peace, and pleasure in one’s existence.

These five elements of education can be sound means to everyone in this world to exist genuinely. In my opinion, this quality education is to be taught at home by parents to children. It is obvious that renowned schools, colleges, and universities are teaching for external affluence; thus, the intuitive growth of a person must be trained at home with the help of ethics and spirituality without being biased of any caste, creed, culture, and color individually.

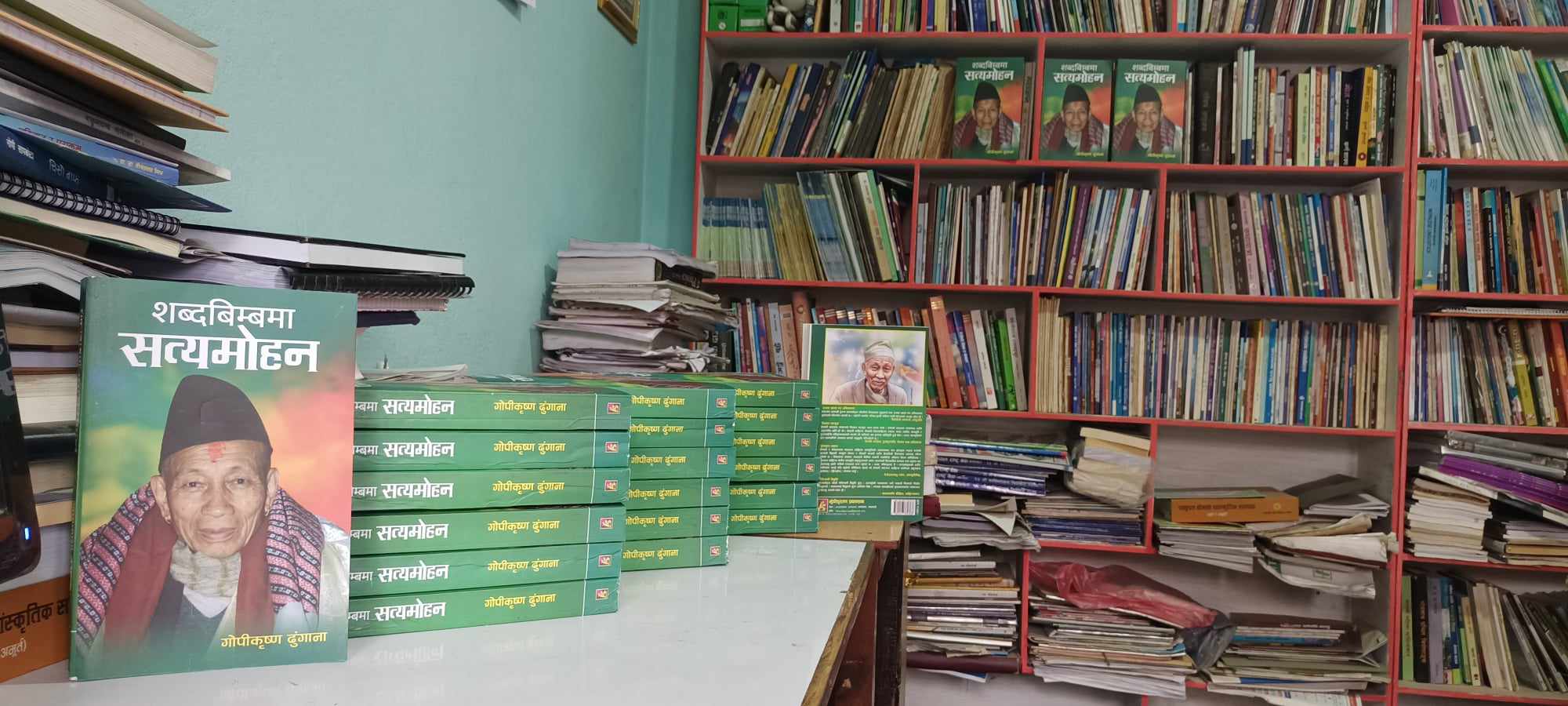

Centenarian Satya Mohan Joshi’s legacies

Centenarian Satya Mohan Joshi has left valuable legacies that deserve recognition from the Nepali people. His life and contributions to Nepali society are well depicted in the recently published book ‘Shabda Bimbama Satyamohan’ was compiled and edited by senior journalist Gopi Krishna Dhungana. The book is divided into seven parts, each related to Joshi’s significant contributions and the legacies he left behind for the motherland. The first part, titled ‘Articles’, consists of 32 valedictory articles. Satya Mohan's own article recounts his visit to the remote Karnali zone, specifically the district headquarters of Jumla, where he faced challenges and triumphs. Born in 1920 in Lalitpur, Kathmandu Valley, Satya Mohan fearlessly ventured into the most remote areas of Nepal after completing his education. His own article takes the lead in this section. Other articles by scholars recognize him as a recipient of the Madan Prize and as a truth-seeking individual. He is portrayed as a multi-faceted personality, a distinguished scholar in various vernacular genres, and a legendary traveler with a postal stamp issued in his honor. The second part, titled ‘Editorial’, includes seven tributes from different daily newspapers. The first tribute from ‘Gorkhapatra’ laments the irreparable loss of Joshi to the nation, particularly in the fields of literature, language, and culture. The second tribute from ‘Kantipur’ praises Joshi for his tireless pursuit of knowledge in various subjects, including literature, culture, archaeology, and more, spanning eight decades. ‘Annapurna Post’ acknowledges Joshi as an innovator in literature, art, culture, history, archaeology, and expresses that his passing has created a void in research on these subjects. Similarly, ‘Nagarik’ recognizes Joshi as a curious mind, a three-time recipient of the Madan Puruskar, and says he was inquisitive in his book Jureli Darshan (the philosophy of the bulbul) and in Nagarjun’s principles in Buddhism throughout his life. ‘Rajadhani’ honors Joshi for his contributions to art and culture, and says it should be acknowledged continuously as his legacy. ‘Nepal Samacharpatra’ illustrates Joshi’s erudition and exclusive dedication to his motherland, transcending castes, cultures, and creeds, while accurately exploring Hinduism, Buddhism, Newa cultures, and other discoveries. Finally, news portal ‘eKagaj.com’ acknowledges Joshi’s exploration of remote areas of the country and his visits to China, where he taught Nepali language and culture, researched the history of currencies, and paid tribute to Araniko's talents. The third part consists of three interviews collected from different news sources. The first interview, from the ‘Shikshyak’ monthly, highlights Joshi’s response regarding the limited subjects for boys in school education during the Rana regime, while girls’ education was forbidden. Even during those days, Joshi studied and published a book on treasured sculptures, emphasizing the importance of cultural studies in Nepal. He asserted that education and culture are two sides of a coin for a nation’s development. The second interview delves into Joshi’s childhood experiences, including his inability to speak until the age of nine, his visit to Surya Binayak temple where he was left unattended so that he could scream out of fear, and the subsequent development of his speech. It also mentions his enrollment in a school in Lalitpur, which he left due to corporal punishment, and his eventual enrollment in Darbar School in Kathmandu, where he was influenced by Sanskrit literature and began his writing journey. In the third interview, Joshi talks about his experiences with earthquakes, his services, his visits to Karnali, and his contributions to the development of cultures, languages, and arts in Nepal. These three interviews serve as milestones in understanding the late Joshi and his accurate contributions to the nation. The fourth part, titled ‘Supplementary’, comprises 17 articles that highlight Joshi’s three-dimensional skills in literature, culture, and administration, with his cultural prowess being the most renowned. He is hailed as an immortal inspirer, a shining star of folk literature, and an ideal man who upheld truth, consciousness, and bliss. The fifth part, titled ‘News’, includes 14 articles that praise Joshi’s extensive works in various fields. It also mentions that his body was donated to a hospital for further studies by medical students. Similarly, it mentions that the Government of Nepal, along with the honorable President and Prime Minister, mourned Joshi’s demise. The ‘Poem’ section features three poets who express their sympathies through rhymes, while the final section, ‘Pictures,’ visually depicts the aforementioned words. In conclusion, by exploring the attributes of this legendary man, it becomes evident that he has left behind persuasive legacies for the Nepali people to carry on, illuminating the future of the nation. Joshi’s legacies can be succinctly divided into three interrelated aspects, which are deeply intertwined in his arduous works: (i) Cultural investigation, (ii) Development of literature, (iii) National and international travel. Joshi’s first legacy lies in his cultural investigations. As the first director of the Archeological and Cultural Department, he initiated investigations primarily within the country. Despite being born in the capital city, he extensively traveled to remote places such as Tanahun, Lamjung, and Sinja in Karnali, collecting folk songs and heritage. Wherever he went, he conducted research unhindered by political or local influences. His book ‘Hamro Lok Sanskriti’ (Our folk culture), the winner of the first Madan Puraskar, is about the folk songs of rural Nepal. Similarly, his work ‘Karnali Ko Lok Sanskriti’ (Karnali’s Folk Culture) explores western Nepal’s ethos. Joshi also visited China to teach Nepali language, literature, and culture at the Peking Broadcasting Institute, where he was celebrated as an innovative scholar. During his visit, he conducted research on Araniko, an eminent artist who had gone to Beijing and built the White Stupa, and compiled a book on him. Recognizing the importance of cultural identity in development, Joshi established the National Theater in Kathmandu, the Archeological Garden in Patan, the Archeological Museum in Taulihawa, and the National Painting Museum in Bhaktapur. He extensively researched archaeology, cultural diversities, and the heritage of Nepal, presenting papers on these subjects globally. Second, Joshi was a model scholar in Nepali literature. He initially learned the alphabet at home and later enrolled at Durbar High School in Kathmandu. He completed his graduation from Tri Chandra College. Influenced by renowned writers like Bal Krishna Sama, Laxmi Prasad Devkota, and Lekh Nath Paudel, Joshi wrote dozens of books in Nepali, Newari (Nepal Bhasa), and English. He was a prolific writer, exploring folk songs, epics, plays, children's literature, grammars, biographies, and more. His literary contributions were recognized with numerous awards, including three Madan Puraskar prizes, the Order of Tri Shakti Patta, Gorkha Dakshin Bahu, Ujjal Kirtiman Rastradeep, and an honorary D Litt from Kathmandu University. Third, Joshi was a pioneering traveler who ventured far and wide within Nepal and globally. As mentioned earlier, he led a team to study the Sinja Valley in Karnali, which earned him two Madan Puraskar awards. He explored most parts of Nepal to collect folk literature and promote the importance of culture and arts, believing that they are the foundations of development and hold intellectual, moral, and spiritual significance. Joshi’s travels were not limited to the nation; he also visited various countries such as India, Sri Lanka, South Korea, Russia, Great Britain, the USA, and Canada. He went to China twice and is hailed as the first Nepali visitor to New Zealand. In conclusion, Joshi’s legacies emphasize the necessity of research in diverse cultures. It is crucial for individuals and universities to prioritize research in various fields as part of our culture. Therefore, this book is a captivating read that will continue to inspire young minds to adapt and innovate in their research endeavors, ultimately contributing to the development of our nation.