ApEx Series: The devastating effects of child marriage

A few months back, a woman jumped into the Karnali river along with her four children. Apparently, she had gotten married as a teenager, and was often abused by her husband and in-laws. The 25-year-old decided to end her life, and that of her children too, as she saw no way out of her plight. No one survived. This, Nirjana Bhatta, national coordinator at Girls Not Brides-Nepal, a network of organizations working against child marriage, says the tragedy was an outcome of early marriage. “Child marriage is wrong and its consequences can be gruesome,” she says. The trouble mostly begins with financial stress that only escalates as time goes on. The pressure of providing for the family falls on the boy while the girl is responsible for handling the entire household and is also forced to meet the expectations of her in-laws. “Majority of them discontinue their education which doesn’t make them eligible for a proper job,” she adds. The matter gets worse when the wife is pregnant which, in most cases, happens within one year of marriage. Many girls are abandoned by their husbands once they bear a child. Bhatta says that the major reason behind this is because the husbands are unable to handle the financial responsibility of raising a family. “With no one to back these girls up, they are prone to domestic violence, especially from their in-laws, or they get kicked out of the house,” she says. Hira Singh Thapa, founder of Social Service Center (SOSEC) Nepal, a Dailekh-based non-governmental organization, says there are nearly 70-80 cases in Karnali alone where girls have been single-handedly raising their children. There are a few marriages where the couple decide to continue their education and that could potentially lead to a better life. But, according to Thapa, the girls are generally unable to continue their education. “Our society is largely patriarchal and families expect their daughters-in-law to look after everything within the household,” he says. The work-load eventually leads them to quit their studies. Despite that, he mentions, several girls work hard to at least pay for their husband’s education. “But, in turn, their husbands look for a ‘more educated’ wife, have extra-marital affairs, and I have even seen a few cases of polygamy,” he adds. In some cases, the husbands go abroad for work, stop sending money back home, and never return. This has forced many girls towards child labor. Thapa recalls an incident from a year back when he was visiting Jajarkot in Karnali Province. He met 15 girls below the age of 18 who were daily wage earners. When inquired, he says, all 15 were mothers working to provide for their children after their husbands disappeared or married someone else. There are also husbands who take care of the family financially but then they are abusive. “It’s the influence of our patriarchal society that gives them the audacity to do whatever they want as long as they make money for the family,” says Bhatta. But the last thing these girls want is a divorce. Bhatta mentions that since most of these girls lack education, or a source of stable income, they are dependent on their husbands. “I know many girls who say they endure abuse only to ensure they have a roof over their heads,” she adds. The situation is even worse for couples whose family don’t accept their marriage, which mostly happens when the marriage is intercaste. “With no place to live, many couples are homeless,” says Kamala Bist, Baitadi district coordinator for Yuwalaya, an organization that works for child rights. In case the marriage does get accepted, there is a lingering conflict of caste and religion which eventually leads to domestic violence. A 23-year-old bartender from Kathmandu, who wants to remain anonymous for privacy reasons, remembers an incident that happened with his friend almost two years back. She, a high-school student, eloped with a boy from a different religion. Although the families were reluctant to accept their marriage at first, they were later convinced. “Her husband was irresponsible, and the in-laws were abusive,” he says. When she reached out to her parents, both of them blamed her for getting married without their permission. She died by suicide. The abuse and pressure of being a young bride/mother has led many girls to develop several mental health problems. Tara Kumari Acharya, a psychosocial counselor for Aawaaj (an organization actively working against child marriage), who has been working in Dailekh in Karnali Province for the past two years, says that around 400-500 people, mostly girls, in her area have been suffering from chronic depression or other psychological issues. “Most of the cases are the outcome of domestic violence and financial stress post early marriage,” she says. She further mentions that this year three girls between the age of 13-17 died by suicide because of the same reason. The repercussions are also seen on the offspring. “They grow up in an environment where either their mother is being abused, or their parents often quarrel, leading them to suffer from mental health issues at a young age,” says Acharya. These children, she adds, fall under the same cycle of early marriage as a way of getting out of their disturbing households. She further mentions that there are incidents where both the parents abandon the newborns. Ten years ago in Dailekh, a couple, both 18, abandoned their two-months-old daughter. The mother left because she didn’t have a good relationship with her husband and the father to attain sainthood. Although her father returned eight years later, he has a health condition. He was unable to take care of his daughter. The child, now 12-year-old, studies in the fifth grade and is being assisted by Aawaaj. Then there is also the problem of not being able to get a birth certificate since the parents can’t legally get a marriage certificate before the age of 20. Although, according to the law, parents aren’t required to submit a marriage certificate in order to receive a birth certificate for their children, Gyanendra Shrestha from National Child Rights Commission (NCRC), mentions that most wards are unaware of that. Worse, many early mothers also don’t have citizenship to begin with. “Many children have been rendered stateless because of this issue,” he adds. The consequences of child marriage is neverending. Many brides are at risk of having health complications from early pregnancies, are forced to live as single mothers for the rest of their lives, or even worse, get married to much older men with the hopes of getting financial and emotional support. “It doesn’t just impact the boy and the girl who get into an early marriage but every other family member, including their children,” says Bhatta.

Suresh Badal on how to become a successful writer

Suresh Badal is a Nepali writer and translator who became a published author in 2021, after the launch of his first book ‘Rahar’. He is also the translator of ‘Hippie’ by Paulo Coehlo. He published his second book ‘Maya Ka Masina Akshar’ in 2022. Anushka Nepal from ApEx talked to Badal about his reading and writing styles. Did you always want to become a writer? I don’t believe a lot of Nepalis think of pursuing writing as a career. But the signs are always there. Even for me, I used to read a lot as a kid. I remember going through every book or magazine that was placed in front of me. And I would often try to write my own pieces, as a way of copying authors that I loved. I think it was because of the societal pressure of having a stable career that I chose to become a microbiologist. It was years later when I finally got back into writing and actually became a published author. What theme do you like to play with while working on a book? My books are usually based on the life experiences of a young adult. Being one myself, I’m able to relate with the struggles and challenges they are going through. It’s mostly relatable for individuals in their 20s or 30s. So I think it’s fair to say that the theme for my books mostly come from my own life experiences. Can you please run us through your process of translating Coelho’s ‘Hippie’? I had read the book before I began working on the translation. But while translating I think I understood the book from more than just one perspective. Usually while reading any book, we try and enjoy the story, finish it, and that’s the end of it. But while translating, I had a chance to go deeper and convey what I understood through my translation. It was like reading something and then making everyone else understand what I perceived. Translating ‘Hippie’ has been the best experience so far. Which authors inspire you? When I was in school, I was mostly inspired by writers like Diamond Shumsher Rana, BP Koirala, and Bijay Malla. I would read every book I could find from these authors. If you talk about my writing, Bhairav Aryal has been the biggest influence. I think, like him, I also like to add subtle humor in my writings, although his works are one of a kind. But like most people, I have an author whom I absolutely idolize. For me that’s Dha Cha Gotame (Dhanush Chandra Gautam). There isn’t a single book of his that I haven’t read. But my favorite is ‘Yeha Dekhi Teha Samma’. Do you have a to-be-read list of books? If you look at my shelves, there are nearly 40-50 books that have been there for almost four months. All of those are on my to-be-read list. I have been a bit busy so I haven’t had a chance to get started. But there are a few books among those I want to read as soon as possible. One is ‘The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida’ by Shehan Karunatilaka and the other is ‘The Satanic Verses’ by Salman Rushdie. I’m also looking forward to reading ‘Shunya ko Mulya’ by Dr Nawaraj KC. What do you think Nepali readers are looking for? I think Nepali readers need a variety of books. We have some established authors but there aren’t that many books being published. This creates a vacuum for readers when they cannot get books that are as good as the ones they read previously. It only pushes them back from reading and hinders establishing a reading culture, especially among youths. I think we need to focus on promoting a bunch of writers so that readers won’t have to wait for a long time to find something they like. Badal's picks Yeha Dekhi Teha Samma by Dha Cha Gotame This book can be considered as the continuation of the author’s book ‘Gham Ka Paila Haru’. The characters are similar to that book. It’s about the life lived in the villages of Nepal, and takes off from where the previous book ended. The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida by Shehan Karunatilaka The Booker Prize 2022 winner written by the Sri Lankan writer Shehan Karunatilaka is a satirical book. It’s actually historical fiction based on the murderous mayhem during the civil war in Sri Lanka. The Satanic Verses by Salman Rushdie Written in 1988 by Salman Rushdie, ‘The Satanic Verses’ is a book that was inspired by the life of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was banned in India and there was even a fatwa against Rushdie because of it. Shunya ko Mulya by Dr Nawaraj KC ‘Shunya ko Mulya’, written by Dr Nawaraj KC, is based on the gruesome reality of women living in Karnali, including but not limited to the suffering and health issues they endure.

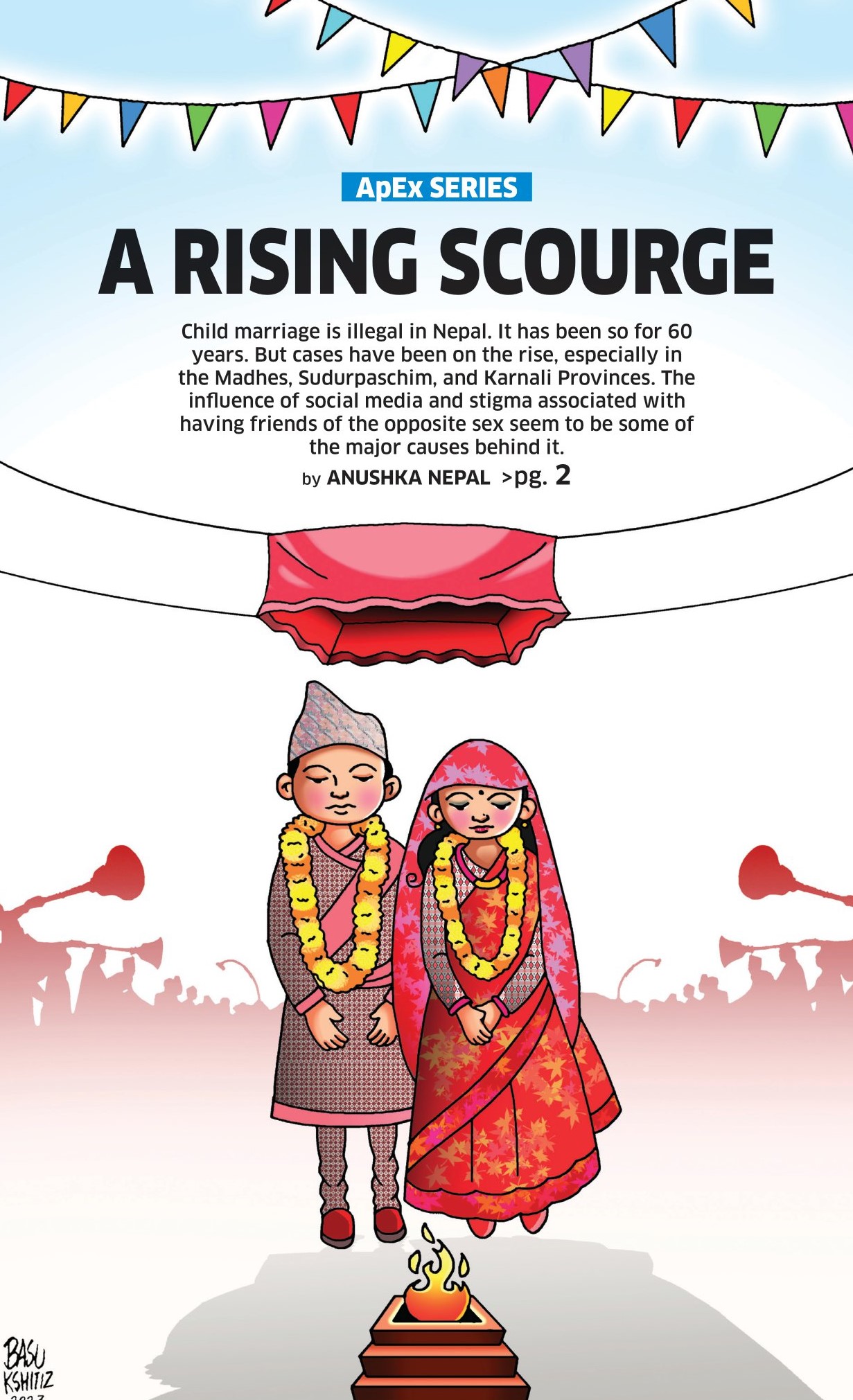

Child marriage; still prevalent and on the rise

Child marriage has been illegal in Nepal since 1963. Both parties must be at least 20 years or above to get married. Despite this, in many parts of Nepal, underage marriage is still the norm.

Kumar Bhattarai, program director at Child Workers in Nepal (CWIN), says child marriage has only been increasing in Nepal. “Around a decade ago, most children would get married because of family pressure. That’s not the case now,” he says. In most cases of child marriages that CWIN has come across, it’s the children who have decided to get married, with some even eloping when their parents refused to accept the relationship.

The number rose during the Covid-19 pandemic, says Dharma Raj Tharu, Bardiya district coordinator for Aawaaj, an organization actively working against child marriage. According to a report—Adapting to Covid-19—published by the United Nations in Sep 2020, the reason behind the rise in child marriages during the lockdown was mainly the closing of schools and loss of livelihoods.

“As most families were bankrupt, marrying off their children was one way of reducing their expenses,” he says. Nirjana Bhatta, national coordinator of Girls not Brides-Nepal, a network of organizations working to prevent child marriage, agrees with Bhattarai and Tharu. She further adds that child marriages are rampant in the Madhesh, Sudurpaschim, and Karnali Provinces of Nepal. One of the many reasons, Bhatta believes, behind the increase in the number of underage marriages, is the influence of social media.

“During the teenage phase, most people need someone to confide in. They need a support system. When parents fail to provide that, they seek comfort from someone else through social media,” she says. This usually results in love affairs, which in turn leads to marriage (and/or elopement). Bhatta claims some parents allow their underage children to get married fearing they will otherwise elope. Many parents are still looking for their children who have eloped and never returned. Most of them, Tharu says, flee to India to get married when their families try to separate them. It’s mainly common in the Tarai belt where the Nepal-India border is easily accessible. “This mostly happens in case of intercaste marriages or when two families come from different economic backgrounds,” he says.

Then there’s also the fact that any form of relationship between a boy and a girl is generally frowned upon in our society, more so in rural areas. This has also forced youths to get married before they are legally allowed to. Nisha Paudel, Surkhet district coordinator for Aawaaj, says, families aside, even schools have made it difficult for children to be friends with the opposite sex. With teasing from classmates, parents questioning their relationship, and teachers inquiring if they are planning to get married, children are forced to believe that marriage is the only way they can stay close to someone they care about. “Most of the time, parents force children, especially girls, to get married because they fear people will speak ill of them otherwise, for having a relationship that’s not validated through marriage,” she says.

According to Paudel, most children getting married in Karnali Province are between the ages of 14 to 19. This taboo and stigmatization of any relationship outside of marriage, Bhattarai believes, has also led to children not being able to have an open conversation about infatuation and physical relationships. “Children, because of easy access to the internet, come across a lot of adult content. To cater to that curiosity, many children decide to marry early,” he says. The curiosity is also fueled by the lack of privacy within the household.

In some of the incidents CWIN has encountered, children have confessed to seeing their parents having sex. “Learning more about this only adds to their desires, and they think marriage is the only way to fulfill that,” he says. Another reason for getting married early seems to be to get out of domestic violence or sexual abuse within their household. “Most children say they would rather have a physical relationship with their husbands than be abused daily by their relatives,” says Bhattarai.

According to Nepal Police, in the 10 months of the fiscal year 2022/23, 26 cases of child marriage have been reported. Similarly, 52, 84, and 64 complaints were registered in the fiscal year 2021/22, 2020/21, and 2019/20 respectively. Although the data shows a decline in the number of child marriages, Poshraj Pokharel, spokesperson of the Nepal Police, says most cases don’t reach the police.

“The media has also failed to shine a light on this issue,” adds Bhattarai. He believes child marriage is on the rise but data says otherwise because of underreporting of cases. Kamala Bist, Baitadi district coordinator for Yuwalaya, an organization working for child rights in Nepal, says parents usually allow their children to get married if the person they choose to marry matches their caste and economic status. This is also one of the major reasons for underreporting of child marriages. The cases that do get reported are when the marriages are inter-caste.

“Because our society still believes in the caste system, families aren’t reluctant to file a complaint in such cases,” says Bist. But the nature of the complaints takes a different turn when children are willing to get married without their parent’s approval. Sagar Bhandari from CWIN’s helpline says that parents, mostly from the girls’ side, try to file a rape case to prevent the marriage. “There are cases where boys have been falsely accused and sentenced too,” he says. The outcome of child marriage is grave.

Children are deprived of education, become victims of domestic violence, and bear children at a young age. In most cases, girls are abandoned by their husbands and in-laws once she gives birth. “These children don’t have anywhere to go since their own families won’t accept them anymore,” says Paudel. Worse, the cycle often repeats with the offspring following in their parent’s footsteps.

Mike Khadka: Beloved musician and radio DJ

Most Nepalis who grew up in the 90s are familiar with the name Mike (Mukunda) Khadka. His songs would be played in most radio stations, a major source of music at the time. Khadka’s fan-base was immense. Even today, decades after his first stage performance, he is remembered for his contribution to the Nepali music Industry. Born and raised in Lalitpur, Khadka was fond of music. People close to him say that there weren't any lyrics he could not remember, or music he could not understand. He was mostly known as a rock musician, but his music taste was eclectic. Khadka stepped into the world by learning classical music as a student of Indian musician Rangarao Kadambari. “He had knowledge for every kind of music, be it Nepali, English, Hindi, or Urdu,” says Prakash Sayami, his longtime friend. Maria, Mohammed Rafi, and Narayan Gopal, were among his favorite singers. In October 1972, Khadka gave his first stage performance, where he sang a number by Elvis Presley. He was discovered by Michael Chand, who used to host musical events at the time. “No one knew Mike at the time, but I invited him to the concert because he was a great singer,” says Chand. “On stage, Mike had the personality of a rock star. He used to wear black most of the time because he wanted to stand out among the crowds.” Chand and Khadka would go on to become lifelong friends. In his early days as a musician, Khadka went by the name that his parents gave him, Mukunda. Mike was a nickname (a variant of the word ‘mic’) that his friends gave him. It is said that he started being known as Mike when he said during one of his performances, “Without mic, I can’t survive.” In person, Khadka was a reserved yet charming man, says his friends and relatives. Sayami remembers how even legendary Bollywood actor Dev Anand was impressed by Khadka’s personality. “We had an opportunity to attend a dinner program with Dev Anand during his Nepal visit, and he gave Mike his blessings and asked him to sit next to him,” says Sayami. “The incident says a lot about Mike’s amazing personality. Everyone was fond of him.” Besides being a musician, Khadka was also a radio DJ, who was adored by his listeners. He was the founder of Classic FM, a popular radio station. “His heart was always into music, which he showed by either performing and recording songs, or by taking up the job of a radio DJ,” says Chand. Throughout his musical career, Khadka recorded hundreds of Nepali and English songs. He was planning to record some new songs and write a book on music when he passed away aged 69 on 23 February. Khadka was diagnosed with bone marrow cancer in January and was undergoing treatment. “With Mike gone, the Nepali music industry has lost a prominent artist,” says Sayami. “He will be sorely missed by his friends, family, and fans.” Mike is survived by his wife, a son, and four sisters. Birth: 14 Jan 1955, Lalitpur Death: 23 Feb 2023, Lalitpur

Bishnu Maya Deula: Doing her best

Bishnu Maya Deula, a 58-year-old living in Kathmandu, has been working as a cleaner at Bir Hospital, one of the oldest hospitals in Nepal, for the past 31 years. The job is in no way easy, she says. It has brought her both physical and emotional stress, but it also gives her a sense of peace, knowing she’s made some difference in people’s lives. She is now also quite well-adjusted to her responsibilities. Born in Chitwan, Deula moved to Kathmandu at the age of six. She never received formal education and says she was never interested in studies either. “I still don’t know how to read or write,” she says. She got married in her early 20s to an army recruit and started working as a cleaner at the Tribhuvan International Airport so that she could take care of her family’s expenses without having to rely on anyone. She worked there even during her pregnancies. “It was a struggle. I had to walk around a lot. I often had swollen feet,” she adds. She left the job once she gave birth, but she joined Bir Hospital before her daughter turned one. Deula was 27 when she became an employee at the hospital. It was a completely different experience for her. At first, she says, the job was traumatizing. But she had to do what it took to make ends meet. She recalls the harrowing first few months of working at the hospital. “Back then, hospitals were not as systematic as they are now, especially for cleaners,” she says. The biggest problem for her was having to clean up everything without any gloves or masks. “I didn’t mind cleaning toilets and hospital floors but cleaning up after every patient was an ordeal. It took time for me to adjust,” she says. Hospitals, at that time, assigned a bucket to each patient, especially the ones who were bedridden. The bucket was for excretion. Having to wash all those buckets, that too with bare hands, she says, was the worst part of the job. It used to affect her even outside of her working hours. “Sometimes I couldn’t eat for days because I would be consumed by the stench of the mess,” she says. Now, she doesn’t have to clean up after the patients as much as she did before. But still, there are some patients who don’t have anyone to take care of them, in which case she steps in. “It definitely gets messy. I feel a little disgusted. But after all these years, I guess I’m used to it,” she says. But the job takes its toll. It can get overwhelming at times. She starts at seven in the morning and works continuously for eight hours, with one hour break for lunch. Although she is assigned to a particular ward, she needs to move with patients from one corner of the building to another, and run errands too when necessary. “Cleaning the ward takes around two hours. The rest of the time I’m always running from one building to another,” she says. It has gotten worse since Deula started having issues with her left knee. She is in constant pain, and she knows standing up for long hours is the last thing she should be doing. But she does it without complaint. “I like to see the positive side of it,” she says. Deula suffers from high blood pressure and diabetes and walking around has served as a workout. “Now, I take way less medications, and I feel a little healthier too,” she says. The job is emotionally challenging as well. “I empathize with the patients and I frequently break down when someone passes away,” she says. It’s especially heartbreaking when someone loses a parent, she says. Having lost her own, she says, it reminds her of the day she lost her mother. “I can understand their pain and I tear up everytime,” she says. It’s the same with parents losing their children. Having lost two children in the past, seeing parents cry over their loss reminds her of her own pain. “I still remember the day I held my children for the last time and when I lost them,” she says, “That pain will never go away and this job never lets me forget.” One of the most difficult times for her was working during the Covid-19 pandemic. The hospital was flooded with patients and a lot of people were dying on a daily basis. Since handling bodies for cremation was mostly done by the housekeeping, she had to spend hours preparing the dead. There was a risk of contamination and seeing so many people lose their life was psychologically disturbing. “I couldn’t help but think about my family. I was scared of taking the infection back home,” she says. Although she had done all of this in the past, Covid-19 was especially challenging because of the patient flow. I ask her if she has ever felt like quitting. She doesn’t hesitate before saying no. Although the job is difficult, there are good memories too. She says being one of the oldest employees, she has earned a lot of respect. “People here treat me well too,” she says, adding it’s heartwarming to see patients who have been admitted for a long time get better and go home. With only four years to retirement, Deula says she’s grateful to the hospital staff and administration for having taken care of her for so long and given her a source of livelihood when she needed it the most. Now, she’s looking forward to her retirement because she feels she has worked long enough. “I want to spend the rest of my time with my family, especially my grandchildren,” she says.

Neelam Karki Niharika on what inspires her to write

Neelam Karki Niharika is a well-known Nepali novelist whose books mostly reflect on feminism and the reality of women in Nepali society. She wrote her first book ‘Maun Jeevan’ in 1994. Some of her other notable works are ‘Beli’, ‘Hawaan’, ‘Yogmaya’, and ‘Cheerharan’, for which she won the Padmashree Sahitya Puraskar in 2016. Anushka Nepal from ApEx talked to Karki to know more about her journey in the field of Nepali literature. How has your experience as a writer been so far? Although I have been a writer for a long time, I think I still have a lot to learn. If I were to talk about my experience, I would like to mention the day of my first book launch in 1994. Back then, I had no idea what a book launch would be like. So the first ever book launch I experienced was my own. It was a surreal moment for me. Since then, I have been trying to live up to the name (and fame) I have earned as a writer. What inspires you to write? If you have read a few of my writings, you will notice that most of my books portray the reality of women in Nepali society. Being a woman, I draw inspiration from the struggles, hardships, and discrimination most women are facing in our society. It was never intentional though. While trying to write something that I could feel connected to, I ended up writing books that are mostly related to feminism. So, to sum it up, women and their experiences, including my own, are what inspire me to write. Are there any authors or novels that mean a lot to you? I have been inspired by every Nepali writer to be very honest, because reading others’ writings is always a good way to motivate myself to work on my own books. If I have to be specific, I think the first thing I ever read, which was ‘Muna Madan’ by Laxmi Prasad Devkota, was something that made me interested in the field of writing. Some credit also goes to the works of Parijat, BP Koirala, Bhanwani Bhikchu, Bhupi Sherchan, and Dhurba Chandra Gautam as well. Their writings are exceptional and I aspire to follow in their footsteps. Do you have a list of favorite books you will never get tired of reading? There are a few actually, and the first one is definitely ‘Sumnima’ by BP Koirala. I have always been a fan of his works, but Sumnima will always be on top. Similarly, there are few other works in the list of my all-time favorites. They are ‘Madhabi’ by Madan Mani Dixit, ‘Shirish Ko Phool’ by Parijat, ‘Jyoti Jyoti Mahajyoti’ by Daulat Bikram Bista, and ‘Ghumne Mech Mathi Andho Manche’ by Bhupi Sherchan. I would recommend these writings to anyone who is thinking of starting their reading (or writing) journey in Nepali literature. Is there a particular book of yours that you are more attached to? More than the book, I’m attached to the characters. As a woman, I can relate to the pain and trauma that most of the characters in the book go through. For instance, even after finishing my book ‘Draupadi Avashesh’, I would still feel like I was carrying a part of Draupadi within me. It is the same with other books like ‘Cheerharan’ and ‘Yogmaya’. It takes me some time to let go of those characters and move on. What advice would you like to give to someone who wants to become a published author? Never be in a hurry to become a published author. Share your work with friends, or someone who will be able to give you feedback on what you’ve written. It’s so easy to share your work through email these days. Getting feedback will help you become a better writer. It’s easy to take those feedbacks and criticism negatively, but it’s important to analyze what the criticism is about, learn to accept your weaknesses, and work on improving them. I would also suggest that you stick to topics you are most comfortable writing about, and read as much as you can on those topics.

Where do unclaimed bodies go?

Binaya Jung Basnet, founder of Action for Social Change, an organization that performs the last rites of unclaimed dead bodies among other social works, says he has incinerated 719 bodies at the crematorium at Pashupatinath Temple in the past 10 years of working in this field. Most of the corpses didn’t have any identification on them, and the ones that did had no known relatives to claim the bodies. According to Nepal Police, in the fiscal year 2021/22, there were a total of 377 unclaimed bodies, out of which only 29 were identified. Similarly, for the first four months of the fiscal year 2022/23, there were a total of 139 unclaimed bodies, out of which only 14 were identified. Most of the bodies found were of men. “Majority of the bodies found are those of the people living on the streets,” says Poshraj Pokharel, spokesperson, Nepal Police. Since every district has a hospital responsible for the post-mortem, the bodies are sent to those particular hospitals to begin the process of identification. “But rarely is there a case when we are able to identify the dead right away,” he adds. The reason behind not finding the identity of these individuals is because most of them have been living on the streets for a long time, and don’t have any known relatives in that area. “We sometimes find generic information like their first name, which is not enough for us to determine their identities,” says Pokharel. Basnet adds that there are some cases when people migrate to another district, with no one searching for them either, so the identification becomes difficult. “Some are also found to be mentally unstable, which is why no one knows who they are and where they have come from,” he says. Still, there are a few protocols that Nepal Police follows in order to identify and find some relatives of the dead, with the assistance of the Department of Forensic Medicine, in the district where the body was found. Once the body is sent for post-mortem, the forensic department first identifies the cause of death, while the police circulates images of the body within its department to check if they have been listed as one of the missing persons in the past. “In most cases, there is no registration,” says Pokharel. The forensic department keeps a record of the body’s estimated age, sex, height, birthmarks or any other distinct feature that might make the identification easier. They take photographs of the body, clothes, and other personal belongings, as well as a sample of their teeth or a bone in case someone is looking to get the DNA tested. All this is done following the Unidentified and Unclaimed Bodies Management Guideline, 2021, issued by the government. The guideline also has a protocol where some of these bodies can be sent to medical colleges for the purpose of studying and examination, if they haven’t been claimed within the timeframe issued on it. According to Dr Govinda Kumar Chaudhary, the head of department for the Department of Forensic Medicine, Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital (TUTH), every year, around 30-40 bodies are sent to various medical colleges around Nepal, that too only from the forensic department at TUTH. Chaudhary further mentions that the main causes of death found so far are pneumonia and liver failure. “Most people we have encountered have died because of cold weather, or alcoholism, and are above the age of 50,” he says. The number of deaths is comparatively higher during the winter season. The dead bodies are kept in the morgue for 35 days to three months, before they are sent out for incineration at the Pashupati Electric Crematorium. Although Chaudhary believes there aren’t as many unclaimed bodies these days as before, there is still a problem of not having enough space at the morgue to store the dead bodies, especially outside the valley. Currently, TUTH is the only hospital that can accommodate up to 150 corpses at a time. The number is quite less for other forensic departments outside Kathmandu. Dr Srijana Kunwar, associate professor at Department of Forensic Medicine, Patan Hospital, mentions that they can accommodate only 10 bodies. The government, however, has decided to allocate more budget in order to expand the space. Because of this issue, the unclaimed bodies need to get cremated as quickly as possible. For the ones found in other districts, Pokharel mentions that the bodies can only be kept at the morgue for around 7-10 days, in order to make space for the new ones that arrive. “This is a huge problem since most bodies get cremated before they are identified,” adds Basnet. There are some rare instances where the individuals are identified, but don’t have any known relatives to claim their bodies. Basnet mentions that, in several cases, families have abandoned their loved ones after their demise at the hospital, since they don’t have money to pay for the funeral. “They end up spending all their money in treatment, and performing the last rites at the Pashupati Aryaghat costs around Rs 18,000 which they cannot afford,” he adds. People who pass away during medical treatment or from a natural cause aren’t sent for post-mortem. They are taken to the Pashupati Electric Crematorium either by the Nepal Police or Basnet and his team. Besides the ones handed over to Basnet, the Nepal Police is in charge of the incineration. Before the establishment of Pashupati Electric Crematorium in 2016, the bodies used to be cremated at the Aryaghat in Pashupati, which Rewati Raman Adhikari, spokesperson, Pashupati Area Development Fund, says wasn’t a feasible solution. “Factoring in the cost, the pollution it creates, and the number of bodies that arrive each day, electrical incineration is definitely the more viable option,” he adds. The crematorium has three incineration chambers, out of which only one is currently functional, and the rest are under maintenance. The crematorium charges Rs 4,000 per incineration, and the Nepal government has assigned a budget in order to pay for each cremation. “I pay for the ones I incinerate, whereas Nepal Police depends on that budget,” adds Basnet. Although the process of cremation is going smoothly, Adhikari mentions that there are days where the number of bodies arriving at Pashupati is above 20, in which case cremation becomes difficult. “It mostly happens during accidents with a large number of casualties, and the hospitals need to clear out their cold rooms,” he says. “In that case, the crematorium is compelled to incinerate two bodies at once.” The problem, Basnet believes, behind the unclaimed and unidentified bodies starts with the increasing number of people living on the streets. “As I also work on rehabilitating these individuals, I know for a fact that establishing a proper shelter for these homeless individuals is the only way of decreasing the number of unclaimed bodies in Nepal,” he adds. Pokharel adds that Nepal Police, along with government authorities are doing their best to tackle this problem, and claims that the number of unclaimed bodies have been slowly decreasing in the past years. “It will definitely take some time, but I’m hopeful that this issue will soon have a proper solution,” he says.

One of a kind coloring book

Published on Oct 2022 by FinePrint, ‘Overlooked Faces of Nepal’ is a Mandala and Mithila art inspired contemporary coloring book for all ages. But it’s also a book that aims to generate awareness about the LGBTIQA+ community and help our society understand and accept people regardless of their gender identities. The artists, Dr Paridhi Sharma and Dr Arpana Pathak, have combined Mandala and Mithila artwork with illustrations that reflect the circumstances of people from the LGBTIQA+ community. The patterns used in Mandala art are clinically certified to relieve anxiety, reduce stress, and induce sleep, which is the main reason why they decided to focus on it. “We wanted to create a book that was therapeutic. We also wanted it to entertain and educate,” says Sharma. The LGBTIQA+ community, they say, has to go through unimaginable hardships and trauma so they wanted the book to be of some catharsis. It could, they thought, be a good way of relieving stress as well. The concept of the book took shape in 2020 during the Covid-19 pandemic, when Sharma and Pathak both resorted to their hobby of sketching as a way of releasing stress and pent up emotions. Although they were both good at art since their childhoods, they say that giving continuity to that hobby became impossible in the later years. But with Covid-19 lockdown, the timing was perfect to revive their skills. “We had no intention of publishing a book. We were just looking for a distraction during that overwhelming period,” says Sharma. Since they were already working on so many illustrations, turning that collection of artworks into a coloring book seemed like a good idea. “It was nothing but a thought. We wanted to share it with our family before proceeding,” adds Pathak, “And I am glad we did.” It was initially just a collection of Mandala and Mithila artwork but Krishna Dhungana, Sharma’s husband and the conceptualizer of the book, suggested they use their skill to do something that had never been done before. They could turn the book into more than just another coloring book by incorporating and highlighting an important social issue. “Our inspiration for the theme was the life story of a close friend of his,” says Pathak. His friend, a lesbian, fell in love with a woman and wanted to get married. But her family was and still is reluctant to accept that. “They both got together in the US, but have been deprived of the love and support a straight man and a woman would get during their marriage,” says Sharma. Their story, Pathak says, was heartbreaking. But there are many others going through similar struggles. “As two straight women, we were far from understanding the pain they had to endure,” she says, although they both knew the gist of it. But just one life story was not enough to inspire their illustrations. “We needed to talk to more people in order to know how we could reflect their struggles through our artwork,” she adds. The duo first reached out to the organizations that worked for LGBTIQA+ communities. But sadly no one seemed interested in what they were planning to do. “It was understandable since all we had was a concept,” says Sharma, “Trusting us must have been difficult.” Luckily, they were able to get in touch with Samaira Shestha, a transwoman, through a make-up artist Sujata Neupane. “We heard her story and it was just the push we needed to bring our idea to life. It felt important,” says Pathak. They met around 30-40 people from the community. “There were days when we would sob our way back home after hearing their stories,” says Pathak. They had help from Shrestha, as well as Malvika Subba and Lex Limbu, the two advisors for their book, who connected them with people willing to share their stories. The aim of this research was to identify the common struggle that everyone in the community faced, which mostly turned out to be the transition phase during their adolescence. “Everyone we talked to had struggled with the change in sexual orientation, identity crisis, and acceptance during that phase,” says Sharma, and that is exactly what Sharma and Pathak have tried to depict through their artwork. Some of the illustrations in the book have beautifully captured the love between two individuals regardless of their gender. “We hope that this book helps initiate a conversation, and help our society understand the LGBTIQA+ community,” says Pathak. More than that, Sharma says she wishes to see their book included in the Nepali curriculum. “My hope from this is that children will be able to freely express who they are, and have a positive outlook on the LGBTIQA+ communities,” she says.