Building exquisite and elegant brands

Inside the studio of Claé Creatives, one notices the minimalist interior, an open plan wood-themed workspace. The place is spacious and the furniture sparse. The word ‘elegance’ comes to mind—and elegance is what this branding agency at Kathmandu’s Naxal is all about.

A subsidiary of the Century Group of Companies, Claé Creatives was founded by Ayushi Dugar in 2020. The studio offers software development, branding, digital marketing, and graphic design services. Their products are simple and ergonomic and without any flash and frills.

These can be seen on the brand designs of companies like Ecoponic Agri Tech of India and Pelvic PT of the US. Clae Creatives is also behind the logos of Cucu Cuddles of India, and Incré of Nigeria.

The studio has offered its services from startups to well-established businesses in Nepal and abroad.

One of the reasons Dugar started the company was to give designers a proper platform to showcase their talents. “I see many designers not being given the recognition they deserve, and this is particularly true if you happen to be a woman” she says. She wants to create a gender-balanced environment for designers, where everyone is encouraged to learn from each other.

Dugar majored in graphic designing and marketing as an undergraduate and did her postgraduate in UI (user interface)/UX (user experience) design. She feels that the design industry in Nepal needs to grow to put out better products and services.

“There is a misconception in Nepal that designing is an easy task, but there are many aspects and processes to it,” she says.

From coming up with logo designing to product packaging to marketing, there are many areas the studio works in. It takes a lot of research and brainstorming to create a unique brand identity.

Claé Creatives helps businesses understand how to brand themselves and shift towards digital marketing.

In terms of software development, the company creates everything from scratch. The entire software is designed around what best suits a particular company and its profile. Also accounted for are how the potential customers are going to interact with the software and how to make their experience enjoyable and engaging.

Many businesses in Nepal do not realize the importance of design and digital marketing, but this is slowly changing, especially after the Covid-19 pandemic when online stores and sales took off.

Asked if it is difficult to get clients willing to invest in branding and digital marketing, Dugar says the answer is both yes and no. While there has been an uptick in the number of companies willing to take the risk and invest in their brand designs and marketing them through digital platforms, she says “there is still a huge gap a studio like ours can fill.”

Claé Creatives itself uses digital platforms like Instagram to inform and educate the people about digital marketing and how it works, and this approach has succeeded to some extent. It has managed to gain several domestic and foreign clients. The studio is already planning to expand internationally, starting from India, to make their services more convenient and accessible for the clients abroad.

The overall goal of Claé creatives is to promote the designing industry of Nepal. Dugar says there are a lot of creative people in Nepal who are reluctant to join a company and put their talent to use. She envisions a comfortable and encouraging working environment for such talents, especially women, so that they will not have to give up on their passion due to lack of a better platform.

“It is much better to work in a team, since it presents more opportunities and learning experience,” she says

Kajol Jha: Providing platform for young talents

Kajol Jha believes in the power of youth. She believes young people can change the world if they are given the right platform. The 29-year-old has been leading Glocal Private Limited, a consulting company that educates, engages and inspires youths to give them the much-needed leg-up in their career.

“Young people, especially teenagers, are so much more capable than what society believes them to be. My goal has always been to offer them a platform to enhance their talents and skills,” she says.

Jha was a driven individual with a strong sense of self from a young age. She joined the company in her early twenties as a blogger for Glocal Khabar. As a writer, she wanted to promote start-ups and young achievers, while encouraging the readers to pursue their own ideas.

“There was a dearth of platforms and information for talented enterprising youths at the time,” she says of her days working as a blogger for the company. “Most stories and articles on youths were negative ones. They rarely featured their achievements, small or big.”

So Jha set out to change that with her write-ups on young and skilled entrepreneurs and their success stories.

Her own personal success came when her company asked her to lead its flagship project ‘Glocal Teen Hero’ in 2015. The project was all about recognizing the ideas and creativity of teenagers from various sectors.

Jha was required to oversee the project’s business and management side, in which she excelled. Her undergraduate study in business administration also came in handy.

But as great as the idea was, it was equally difficult for Jha and her team to find collaborators to start the project.

She says Nepali society is by and large reluctant to place their trust on young people, let alone teenagers with innovative ideas out of which they could build a career. Many prospective collaborators dismissed the project upon learning that it was about teenagers. Parents were also reluctant to allow their children to participate.

But Jha was determined to make the project happen at any cost—if anything, the pushbacks galvanized her. After much convincing, she and her team were able to rope in five collaborators for the project.

“We had 98 participants in the first iteration of Teen Hero project. The number has gradually increased over the years, reaching 611 in 2021” Jha says proudly.

Glocal Teen Hero is held annually where young talented minds are awarded for their works. While the cash prize helps winners improve and expand their enterprises, it is the business network and opportunities that open up that is more important.

“More than the cash award, Glocal Teen Hero is about giving winners the recognition among business leaders and entrepreneurs,” Jha says. “Being recognized among these individuals opens several doors of opportunity that helps them pave their career path.”

Over the years, the Teen Hero project has also gone international, with its own version in India, Sri Lanka, Pakistan and Bangladesh.

“We want to turn this into a global community of change-making teenagers. This would provide a space for creatives from all over the world to share and work on their ideas,” say Jha, who is currently fulfilling the role of associate director at Glocal Private Limited.

Besides promoting the works and ideas of young people, Jha is also involved in the company’s e-learning platform, Glocal After School, where young individuals are given opportunities to upskill and taught to sharpen their skillsets.

It is important for Jha to make learning methods more effective and practical, particularly in the context of Nepal where many youths are traveling abroad for jobs and training.

“The vision is to promote an ecosystem of skilled youths through these trainings, ensuring the availability of jobs as well as skilled human resources within Nepal,” she says.

Jha works with equally talented and driven team members who share the passion for fostering youth entrepreneurship. They have helped many individuals on their career path at a very young age.

“If anyone can change the world, it’s the young generation. All they need is a proper platform where they can learn to hone their skills,” says Jha.

Dr Bhampa Rai obituary: A relentless campaigner for refugee repatriation

Dr Bhampa Rai, a leading figure in the Bhutanese refugee repatriation movement, passed away on June 19. He was 72.

Rai was born and raised in the Bara village of Samchi district in southern Bhutan. His ancestors, originally from Nepal, had migrated to Bhutan during the 17th century.

A surgeon by profession, Rai worked for the Bhutanese royal family before tens of thousands of Nepali speaking Bhutanese fled the country in the early 1990s.

Unlike other Nepali-speaking Bhutanese, Rai and his family were not chased out of the country. As a surgeon to the royal family, the Bhutanese government in fact urged him to stay. Rai left as he could not tolerate the government’s persecution of his people. The stateless people, he felt, needed him more than the royal family.

Rai and his family first made their way to West Bengal, India, where they spent a few months with the other refugees. There he met Ram Karki, a Bhutanese human rights activist now based in the Netherlands.

“He was straightforward and selfless and he wasn’t against any group or community, only against the regime that had evicted his people from their homes,” says Karki of Rai.

After the homeless Bhutanese refugees were chased away by the Indian authorities, they came to Nepal and camped along the Mechi River in eastern Nepal. Life became increasingly hard for them. There were crises of food, water and sanitation, and the people started getting sick.

Rai volunteered medical care to the sick, and he continued his practice even after the refugees were moved to the camps run by the UN High Commission for Refugees.

“He had a clinic in Damak from where he used to offer free healthcare to Bhutanese refugees as well as non-refugees,” Karki says. “He used to get hundreds of calls every single day and he helped everyone.”

As a qualified surgeon, there was no shortage of well-paying job offers for Rai. But he declined them and decided to devote his life for the care of his people.

Rai hoped to one day return to Bhutan and led a repatriation movement to find a rightful place for his people in their native land. He didn’t give up even when the majority of refugees opted to migrate to other parts of the world as part of the UN's third country-resettlement program.

Rai's parents as well as his wife died in Nepal as refugees. He had been living alone in his rented flat.

In May this year, Damak Municipality had honored Rai for his tireless service to the refugees as well as to the local community. He was offered free housing, but for him home was always Bhutan.

“On the day he was honored, he had shared with me his wish to live out the last of his days in Bara, Bhutan,” Karki says. “That wish never came true. Now it is upon us to walk on the path he has shown.”

Rai had been suffering from liver and kidney problems for a long time. On June 14, he underwent operations for hernia and piles and later died of complications from the surgery at Noble Hospital in Biratnagar.

InDepth: Working out the right combo

Nepal’s installed power capacity is expected to exceed 15,000 MW by 2030, according to the Electricity Demand Forecast Report 2017.

By 2040, electricity demand is projected to climb to 82,000 GWh, with a corresponding installed capacity requirement of over 35,000 MW.

Hydropower plants are believed to be Nepal’s most reliable energy-source. In theory, the country can produce 50,000 MW of electricity by harnessing its water resources. But there are challenges galore to turn this theory into practice. For one, cost is a big concern.

Dipak Gyawali, former minister of water resources, says Nepal’s electricity production is three to four times more costly than it is in most other countries. “For instance, Ethiopia started producing electricity without foreign assistance and did it at $800 per kilowatt. In Nepal, we had to fork out $2,500 for the same output,” he says.

Building hydropower plants in Nepal is both challenging and costly because of the country’s difficult hill and mountain topography, often with no road access to the project sites.

“A power plant that takes five years to build elsewhere takes 10 to 15 years in Nepal,” says Gyawali. While technology and expertise have helped reduce both time and cost of building power stations, that is true mostly in the case of storage-type hydropower projects. In Nepal, most hydroelectricity projects are run-of-the-river, which don’t have the desired power storage capacity, or the consistency: During the dry season, electricity production of hydropower stations falls by two-thirds of their peak monsoon-time output.

According to the Department of Electricity Development, Nepal has the electricity generation capacity of 2,094.034 MW, of which 20.18 MW comes from solar sources.

Nepal has set the target of ramping up its clean energy output from 1,400 MW to 1,500 MW by 2030 as part of its Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) pledge to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. But the achievement of this goal remains doubtful, given the country’s patchy record. Nepal had failed to meet its previous NDC target: to expand renewable energy to 20 percent of its energy-mix by 2020. The share of renewable energy was a mere 3.2 percent in 2019, government data show.

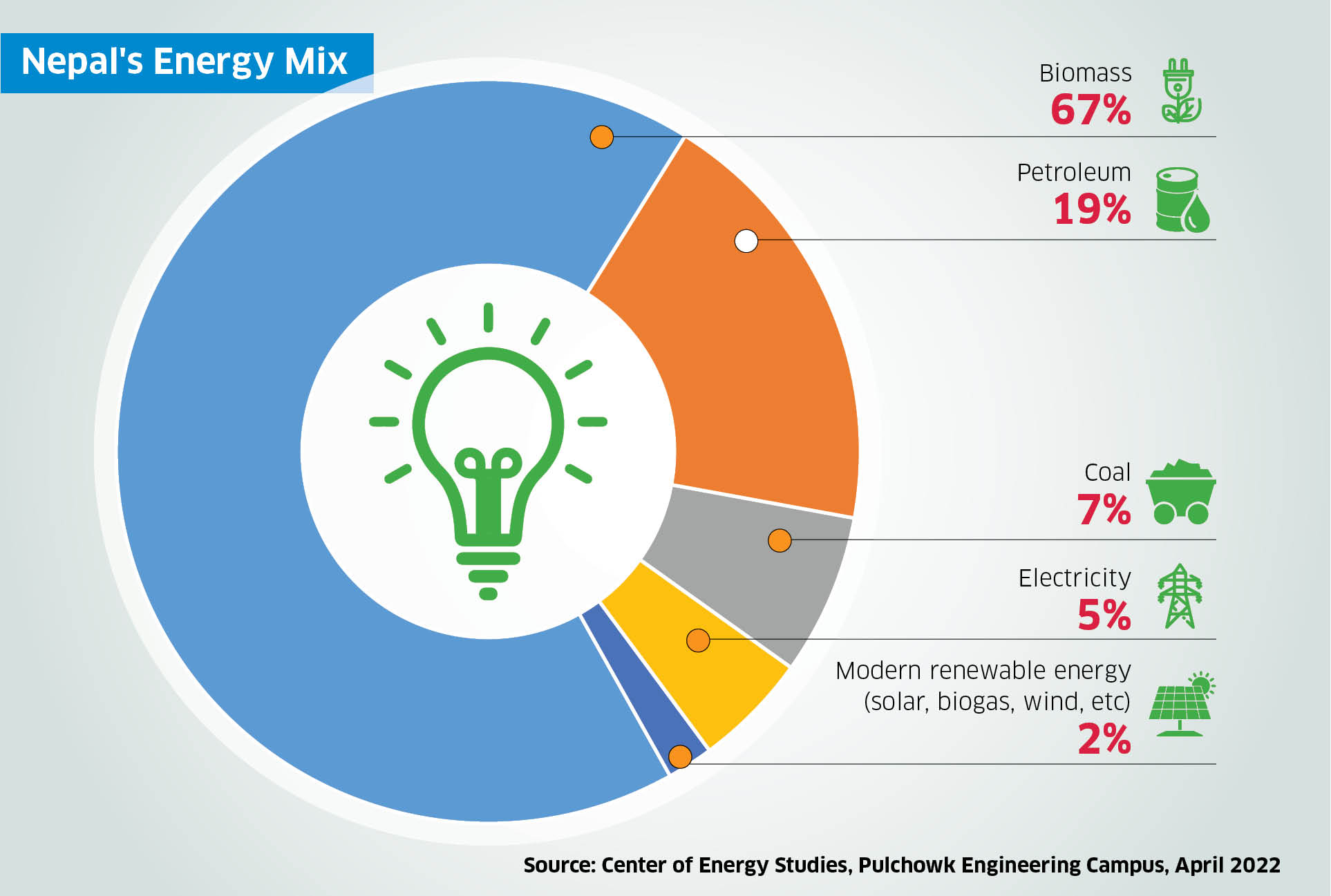

According to a study carried out by the Center of Energy Studies, Pulchowk Engineering Campus, in April 2022, Nepal meets 67 percent of its energy needs from biomass, 19 percent from fossil fuels, seven percent from coal, five percent from electricity, and two percent from alternative sources.

In order to meet the NDC target, say energy experts, Nepal must prioritize clean alternative energy sources alongside hydroelectricity projects.

Solar and biogas technologies could be cheap and viable alternatives, for instance. Solar panels can be set up in each household in a day or two, and approximately a year in case of large-scale production facilities. Likewise, a household biogas system can be installed in two weeks. Madhu Sudan Adhikari, Executive Director of Alternative Energy Promotion Center, believes it is high time Nepal prioritized energy sources other than hydroelectricity to meet its energy needs.

“Generating solar energy is far cheaper than generating hydro energy,” he says. “The cost of building a one MW-capacity hydro plant is around Rs 200m. The same amount of electricity can be generated via solar technology for Rs 70m to Rs 80m.”

But there is a catch. Harnessing the sun’s energy may cost a lot less than generating electricity from water, but solar plants’ power availability factor—a measure of efficiency—of 18 to 20 percent dwarfs that of hydropower stations at 30 to 40 percent. There is invariably a trade-off.

Jagan Nath Shrestha, a solar energy expert, believes both hydro and solar plants can be simultaneously developed, so that energy production does not fluctuate.

Also, finding a large enough area to set up solar panels to support large communities is a big concern, especially in a crowded city like Kathmandu where open spaces are rare.

But this problem also has a solution, says Shrestha. “If, say, 100,000 of the bigger, well-spread houses in Kathmandu valley install solar panels, the surplus electricity they produce can be used to offset any shortfall in the national grid,” he adds.

Better yet, say energy experts, solar technology should work in concert with the biogas systems in rural Nepal where most families still rely on traditional, polluting energy sources like firewood.

It is more costly to install solar panels in individual rural households compared to their installation cost for urban households. But there is plenty of space available in non-urban areas of Nepal to set up small- to medium-size solar facilities to light up small communities. And for biogas systems, they already have easy access to organic materials.

“It takes approximately Rs 100,000 for a household to set up a biogas system for cooking or heating purposes,” says Shekhar Aryal, chairperson of Biogas Sector Partnership-Nepal.

According to Aryal, nearly 1.4m rural households in Nepal have the capacity to produce biogas (at present, only half a million do).

Mass-produced and environmentally-friendly briquettes—compressed blocks of coal dust or renewable products such as paper, sawdust, wood chips and agricultural wastes—can also come handy as many rural areas are inclined towards traditional energy production.

Both hydro and alternative energy sources have their benefits and drawbacks. The goal is not to choose one over the other, suggest energy experts, but to come up with the right mix so as to meet our household and industrial power needs while keeping our environment sufficiently clean.

Shekhar Chandra Rai: Kathmandu’s passionate traffic volunteer—and no, he is not from Japan

If you commute through Kathmandu’s Ring Road route regularly, chances are you have noticed him. A lone figure in a boonie hat and a reflective vest standing in the middle of a busy road intersection, gesticulating at motorists to stop or to move.

I might even wager that chances are you have heard somewhere that he is from Japan. Yes, he is a traffic volunteer; and no, he is not from Japan. This I discovered (rather embarrassingly, I must admit) from a police officer at Gaushala when I asked him if he could help me contact the Japanese traffic volunteer for this piece.

When I finally meet the man, he tells me that he gets misidentified as a Japanese national all the time, assuring me that I am not the only one.

Shekhar Chandra Rai has been working as traffic marshal for over a decade now. The misinformation about his Japanese origin spread as a result of a news article published in 2006.

“There was this news article about an actual Japanese volunteer who handed a traffic signal violator to the authorities,” he says. “Since the article didn’t publish his picture, people started assuming I was that person.”

Born and raised in Morang district, Rai left for Brunei to work in 1993. He worked for the royal family of Brunei for two years before returning to Nepal.

“After I returned to Nepal, I didn’t work for a long time,” the 47-year-old says. “I used to idle my days away in the Jamal area, watching vehicles pass by.”

He used to watch traffic officers at their job, fascinated how they controlled and guided the flood of vehicles. He would assist the traffic officers when the congestions were too high. The officers were more than happy to have an extra hand, particularly during rush hours.

Rai learned while volunteering that the task required a good problem-solving skill and a lot of patience, which made him appreciate the job of a traffic officer even more.

In the run-up to and after the People’s Movement of 2006, street protests and rallies became fairly common in Kathmandu. Traffic jams also became frequent as a result. It was then when Rai began volunteering on a regular basis.

“I used to stand in the middle of the Gaushala and Chabahil intersections for hours, managing the traffic,” he says. “I worked during rush hours at first, but soon I was spending more than 12 hours in some of the busiest streets of Kathmandu.”

Rai doesn’t own a vehicle, so he hitchhikes or takes a public vehicle to wherever he feels his help is needed. He really seems to get a kick out of this volunteering gig. Otherwise, there is no explanation as to why anyone would spend hours upon hours dealing with Kathmandu’s notorious traffic —and mind you, he is just a volunteer.

His eyes widen with excitement when he talks about the old days, back when Kathmandu’s roads were narrower, overhead bridges were few and far between, and the traffic situation was absolute chaos.

“Oddly enough, those are the days that I cherish and find the most memorable,” he says.

Rai has a fixation with fixing problems. He tells me about the time he gathered some people to unclog the rainwaters that had waterlogged a road section in order to keep the traffic moving.

But since Rai doesn’t wear a traffic uniform, motorists do not always heed to his instructions. He has no authority to issue tickets to traffic rule violators, so he is sometimes rebuffed by motorists. There have been numerous occasions when he has come across argumentative and hostile drivers.

“I am simply here to volunteer. I try to avoid arguments as best as I could,” he says.

This approach doesn’t always work though. He tells me he was once nearly assaulted by a motorcyclist in Tripureshwor.

“I stopped him for breaching the traffic rule and he nearly hit me. Fortunately, at that exact moment, a police officer happened to be passing by, and he protected me from getting beat up by this motorcyclist,” Rai says.

The difference shown by the police officer in front of the gawking motorists and passers-by at the time made a lasting impression on him.

But not all motorists are rude to him, he says. “They understand that I am there to help and they are cooperative. I wouldn’t be doing this if my work was not being appreciated,” he adds.

Kathmandu has changed a lot since Rai started volunteering: roads have become wider, traffic lights and other infrastructures have improved, and people’s sense of traffic rules have also improved to an extent.

“It is a lot better now. But that also means I am a lot less busier,” he says.

Rai’s volunteering work has won him accolades from traffic officers as well as the government of Nepal. He was feted with Prabal Jana Sewa Shree, one of Nepal’s highest civilian awards, by the president in 2020.

With more time on his hands, he divides his time between volunteering and running hotel, his family business, in Gaushala these days.

“I still like working as a traffic volunteer but there is little to do for me nowadays. I get bored when there is no problem to solve out in the street,” he says.

The burdens of a Nepali woman

“Where do I start?” asks Bhumika Thapa [name changed] as she reminisces about her pre-marriage days when she got to work, travel abroad and enjoyed considerable financial independence.

Thapa came to Kathmandu after completing her secondary education, started working when she was 19, and got married at 25.

Thapa, now 47, says she was worn down by the marriage. “It was one-sided love from my husband’s side. I was compelled to marry him after he threatened to take his own life,” she adds.

The society didn’t help her at the time either. Thapa was emotionally coerced by the people around her into marrying the man she had no feelings for whatsoever. She was told that she would soon be past her marriage age, and she relented under duress.

“It was the worst decision of my life, which I realized the day before my marriage,” Thapa says. But she could not walk away from her marriage. “That would put my family’s reputation on the line.”

And so Thapa chose to submit to patriarchy, to silently suffer.

What’s worse, her professional success in the development sector became her worst enemy. “I earned more than my husband and that hurt his ego,” she says.

She had her daughter at 27 and a son at 35. Thapa says she had to give up her career because of the pressures she faced in her personal life. “I alone had to look after the household and the needs of my in-laws,” she says.

This gave her little time to focus on her career and spend time with her children. Her health also deteriorated because of the stress and workload. Giving up on her career was the only way she could look after her children.

Thapa feels trapped. But she still hasn’t lost hope. “I will soon be working remotely for a company to make some money for myself,” she says. She also talks of her plans to live separately once her children grow up.

But not every woman is as headstrong as Thapa. Kalpana Prasai [name changed] is a 55-years-old homemaker who has spent most of her post-marriage days cooped up in the kitchen.

“With the amount of time I have spent in the kitchen, I should have probably opened a restaurant. At least, I would then be financially independent,” she says with a wry smile.

She wakes up at five every morning so she can have at least a couple of hours a day to herself. At seven o’ clock, she enters the kitchen and after that she has no idea when the work will end.

Prasai has to cook at least five meals a day to satisfy her exacting husband and then separate dishes for her two sons.

I spent a considerable amount of time with Prasai, interviewing her while she worked in the kitchen. She only got to sit down to have lunch at around 1 pm, after preparing meals and feeding the entire family. Every now and again, her husband would show up in the kitchen to either complain that the food was not to his liking or to get an update on his meal.

“In 30 years of our marriage, not once has he cooked a meal for himself,” she says of her husband.

Even when they are invited to their relatives’, Prasai says, she needs to cook at least one food item for her husband. “Otherwise, there would be a scene,” she adds.

Prasai’s sister-in-law, who was present at one point in this interview, confirms the food habits of her brother. “The whole family has gotten used to his behavior, even though it can sometimes be disrespectful,” she tells me. “But there is lots of love between the two,” she quickly adds.

Prasai regrets not having a proper career and choosing to become a stay-at-home wife and mother.

“I had the qualities of a leader, but it’s too late now,” she says in a diffident tone.

The experiences of Prasai and Thapa illustrate how our societal structures deprive women of a say, be it in their work, household, or way of life.

“A woman is rarely given a position of authority and even if she is, her role is seldom acknowledged,” says Shraddha Verma, a 26-year-old who also works in the development sector.

Her work requires her to make several field visits outside Kathmandu, and she tells me she has to work twice as hard just to get the same respect people give to her male colleagues.

“Even when I am supervising a certain project, people are reluctant to come to me with their concerns. They want a male officer,” she says. “Our society is yet to come to terms with the fact that women can lead, become figures of authority.”

Verma says she too has internalized some patriarchal beliefs. “Sometimes I put a certain restriction on myself, just because of my gender,” she says.

Sewa Bhattarai, a freelance writer and a new mother, also admits to having moments of realization of her patriarchy-influenced actions and decisions.

“I am well-educated and come from an understanding household. So people assume I haven’t been influenced by patriarchal beliefs. But nothing could be further from the truth,” she says.

The 37-year-old has faced her own share of struggles living in a society where men set the norms.

A woman —educated or illiterate, rich or poor, modern or traditional—is constantly judged and questioned by our society. Again, Bhattarai’s current lifestyle can be an emblematic case here. She and her husband decided to stay with each other’s parents a month at a time. And there were people who had problems with this arrangement.

Bhattarai would hear comments like: “This is not your home anymore,” “You should not be living with your parents after marriage”.

“If it is normal for me to live with my husband’s family, why is it so hard for this society to accept that the husband may also choose to live with his in-laws?” Bhattarai asks.

She shares a recent incident at the local ward office where she had gone to make the birth certificate of her daughter. Bhattarai wants her daughter to have both her and her husband’s surnames, but her request was refused outright.

“They told me only the father’s surname can be used,” she says. “It is infuriating that I live in a society that doesn’t allow a woman to pass on her name to her child.”

Prasai faces a similar predicament. Her husband is an Indian citizen, but her sons identify as Nepali citizens.

“I have a Nepali citizenship, so I tried to refer my sons for Nepali citizenship from my side. But I was told that that would work only if the father of my sons is unknown or has passed away,” she says.

From homes to neighborhoods to government offices, Nepali women are treated as second- class citizens. Women are still seen as subservient figures everywhere they go, and this has become normal for many of us.

“What’s scarier is that our society has failed to hold people accountable when a woman is wronged,” says Meena Uprety, a sociologist. “If a woman gathers the courage to speak up against her abuser, more often than not it is the woman who is questioned by the society.”

Even in cases of rape and sexual harassment, the survivors are the ones who get dragged through the mud for daring to share their story and demanding justice. Actor Paul Shah was accused of raping a minor girl and still rallies were held in his support.

“When people rally on behalf of a rape-accused, it says a lot about our society,” Uprety says.

Punit Sarda: Domestic goods should get priority

With the government's decision to waive 90 percent customs duty on the import of sanitary pads, domestic manufacturers are worried their sales will be hit. They fear that their customers will gravitate towards foreign brands. Anushka Nepal of ApEx talks to Punit Sarda, the CEO of Jasmine Hygiene, which has been manufacturing sanitary pads, baby diapers, and face masks for the past 15 years, about the effect of this import duty waiver.

How will this waiver affect the domestic production of sanitary pads?

One thing we can be sure of is that our market will be flooded with imported goods. People are already reluctant to buy domestic products. With this reduction on import duty, there is a chance that the customers we already had might also shift towards foreign products because of the reduced price. This causes a ripple effect in the production of sanitary pads. When we are not given space in the market, there is no way we will be able to profit, let alone break even. This will make it impossible for the domestic manufacturers like us to sustain.

Why do you think people are reluctant to buy Nepali products?

I would pin it down to three things. First is the lack of branding. While multinational companies already have well-established brands, domestic companies are not given the space to place their products. This disparity makes it difficult for domestic companies to stay in the game. Secondly, it is the ‘imported goods are always better’ mentality that all Nepalis grew up with. We blindly believe that the quality of all Nepali products is inferior, without even giving them a try. Yes, I do admit that sometimes the quality of domestic products might not be up to the standard of imported products. Then again, how will domestic manufacturers improve their products if they are forced to bankruptcy? And lastly, I believe that the government itself is not being supportive enough to uplift local businesses.

What should be done to convince people?

Local manufacturers should be given a proper space to sell their products in the market. Right now, they don’t even get a properly space to keep their items in stores. And even if they do, it will be because of the profit percent they have increased for the storeowners. This shows how domestic companies are already at loss from the start. Not many of us know the sanitary pads that come from India are not certified, whereas ours are. But this fact gets ignored since branding has played a major role to push the sales number of imported products. Meanwhile, domestic companies are simply not given a proper platform to advertise their products. Customers should be given the opportunity to try both Nepali and foreign products and decide for themselves. But this is not the case in our country.

What should government do to help local businesses?

The only solution that I see government can do is increase the customs duty, not just on sanitary pads but all simple daily use products. We as a country have become reliant on other countries for everything, even for a product as simple as toothpastes and soaps. These products are simple enough to manufacture within the country and there are companies that have been manufacturing them. But these companies are not getting the platform to sell their goods. Government should create that platform, so that these locally manufactured products can find customers.

Will this waiver also affect other domestic products other than sanitary pads?

If a chain has a weak link, there is definitely going to be some sorts of trouble. It causes a ripple effect. While we are continuously being weaker in one part of our production, multinational companies are benefiting from this loss. While we are struggling to sustain our industry, they are getting a chance to improve on their other products. For them, selling their products won’t be a problem since they are already well-established brands. Domestic companies like ours have been put at a disadvantage by this waiver. We might one day lose our customers for baby diapers and face masks as well.

Suresh Badal: From probing microbes to poring over prose

“Life finds a way to connect one with their passion,” says Suresh Badal, a writer and translator.

From a very young age, Badal was interested in books and literature. He collected books, even discarded and dog-eared ones, and gave them bespoke hand-crafted covers if necessary.

Even though he loved literature, he studied science to become a microbiologist. “I grew up in a society that believed science to be the superior subject,” he says.

Badal did sometimes have the urge to leave the field of science and study humanities, but he never took the step. He got a master's degree in microbiology and started working as a teacher.

By this time, his literary dream was long behind him. But this changed after he was involved in a motorcycle accident in 2012.

Badal fractured his leg in the crash and never quite recovered fully. He was unable to stand for a long period to teach his class.

“My work became a hindrance to my health,” he says.

Four years after the accident, Badal's condition deteriorated and he was completely bedridden. It was a difficult situation, but also a blessing in disguise.

“My illness gave me the opportunity to connect with my passion,” he says.

Everyday, Badal spent his time on his laptop, reading and writing. He kept a positive outlook where others might have suffered a mental breakdown. Literature saved him.

“Physically, I was incapacitated; but I was traveling the world through literature,” he says.

Badal read a lot during those days and also posted his writings on his social media.

“Cooped up inside my room, I wrote about the outside world,” he says.

Most of his writings were autobiographical in nature to which many people related to. Unbeknownst to him, his work was getting recognized, and soon he got a call from a publisher.

Badal’s first book Rahar was published in February 2021. It was a compilation of the works that he produced while he was bedridden. Most of the writings were about his childhood experiences.

The book was well-received by the readers. Badal was then approached by a publisher to translate Hippie, a novel by Brazilian author Paulo Coehlo, into Nepali. The book came out in October 2021.

“For me, it was an amazing opportunity to share my understanding of the book with other people,” Badal says. “More than work, it was a fun experience.”

Translation, he adds, is “portraying the essence of the book” in a different language.

Badal enjoys writing and translating with equal measure. He feels lucky that he is getting to follow his passion.

“Do you have any frustrations about not being able to follow your passion sooner?” I ask him.

“I would not call it a frustration,” he replies. "I never resented the fact that I studied science. But I do wonder that if I studied humanities, I would also be writing in English.”

Badal writes in Nepali but he is heavily influenced by western literature.

“I mostly read English books, but I express in Nepali,” he says. "Maybe, this is also one of the reasons why I am fond of translation."

Badal wishes more books from around the world should be translated into Nepali. “Language should not be a barrier to literature,” he says. "There aren’t many genres to explore within Nepali literature. We need literature from around the world and translation can make this possible."

Badal is currently working on a romance novel titled Maya Ka Masina Akshar, which will be out this year.

He plans to continue writing, translating and reading, but he also believes that life and career can change anytime. The motorcycle accident that made him a writer out of a microbiology teacher taught him this

“I am a believer of destiny. Let’s see what it has prepared for my future,” he says.