Mahadeva in the eyes of Daksha

Accounts of Mahadeva borrowed from Daksha’s tirade against the latter offer glimpses of the Mongoloid culture of those days. Daksha of course dislikes everything about Mahadeva. They include a coat of ashes from the crematorium on his body, tiger hide around his waist and elephant skin, his habit of consuming cannabis and Dhaturo (thorn apple), angry red eyes and his dance, performed with utter abandon, the use of snakes as ornaments, matted hair as the crown, his company of ghosts, vampires and evil-eyed spirits, his damaru—a two-headed drum—which he plays with the right hand while holding a trident in his left and the way he walks—like a naked drunkard without shame. On the other hand, Daksha describes the guests he has invited (the Aryas) as wearing ornaments studded with gems and rubies, with the paste of sandalwood, musk pod and saffron flowers applied to their skin. They enjoy the sweet songs and the music of the Gandharvas, the dances of the nymphs (the Apsaras) and come from clean holy places. In the eyes of Daksha, Mahadeva is a wayward lunatic, a nobody, literally, whereas the four-faced Brahma and Narayana are important entities as the Creator and the Preserver, respectively. But a war between the armies of Mahadeva and Daksha proves otherwise. The war ends with the defeat of the forces of Daksha and the latter’s beheading. Upon requests from Daksha’s wife Virani and other deities, Mahadev pardons Daksha and revives him by installing on his decapitated body the head of a he-goat. The war ends up consolidating the position of Mahadeva (Shiva) as he becomes the Destroyer in the new divine power structure. Vishnu had first sided with Daksha in the ear, perhaps along ethnic lines, only to leave the battleground in the midst of the war, most probably to avoid a prolonged war with Mahadeva. The Aryan-Mongoloid cooperation was the need of the time, as exemplified through the support Mahadeva extended to the terrified deities to counter the evil-minded mighty Asuras such as the Tarakasur, the support Vishnu provided to Mahadeva in getting Satidevi and in subduing Jalandhara, who presented himself before Mahadeva’s consort Parvati in the guise of Mahadeva. Scriptures describe Mahadeva as the most kind-hearted and generous among the Trio as he readily grants wishes to his devotees, regardless of who they are—the Daityas, Danavas, the Asuras or the Humans. Manifestations of the Shaktipeethas Literally, Shakti means power and Peetha means the seat. Thus, Shaktipeethas mean centers of power, shrines where the divinities (goddesses in particular) are worshiped. The South Asian subcontinent, including Nepal, has a number of such centers of divine power. After the death of Satidevi, Mahadeva literally lost his senses and started roaming all over the world carrying her body on his back. The body would not decay and fall apart as Mahadeva was carrying it! Mahadeva not discharging his duties had the world in disarray. So, to bring Mahadeva back, Lord Vishnu, upon a request from the deities, worked out a solution. He created flies, which would cause Satidevi’s body to decay and fall. Brahma is credited with creating Shaktipeethas on the spots where the organs fell. Among these places, Guheshwori (Kathmandu) is where Satidevi’s reproductive organs fell, as per Swasthani Vratakatha. Per the scripture, her chest fell in Kamarupa, head in Varanasi, right ear in Paurandha, tongue in Kashmir, left ear in Purnagiri, nails in Chamundachal, right hand in Astachal, left hand in Ekabir, neck in Kamaroshtha and the right foot in Kailash Mountain, even as Mahadeva continued to roam around the world. This hints that our cultural spheres covered a large geographical area at that time. Mahadeva alone roamed from Kailash in the Himalayas to the shores of the Indian Ocean, Persia in the west to Bali in the southeast. According to the scripture, all of the Peethas dedicated to Brahma, Vishnu, Surya Narayana, Ganesha, and Bhairava have their unique identities. It says these divine power centers have different forms based on communities and their conventional practices. The scripture advises communities to well understand their family and community traditions, and perform rites and rituals at these centers of faith accordingly. This advice makes sense, given differences from place to place and people to people in terms of cultural, religious, spiritual practices and rituals. Such accommodative and tolerant views allow people to worship a wide range of sages, deities, icons and places.

Aryan-Mongolian amity, enmity in focus

The word ‘Swasthani’ is a combination of swa, sthana and i. In short ‘swa’ means one’s self; ‘sthana’ means location, mainly spatial and sometimes temporal or even contextual; and the suffix ‘i’ here converts a word into feminine form. Looking at the name of the book, Swasthani is addressed as ‘Sri’, a polite form of addressing an individual. ‘Sri’ has multiple meanings, including the supreme consciousness, the goddess of prosperity and wealth. The Vedas consider ‘Sri’ as Goddess Parvati, the consort of Lord Shiva. It is interesting that Goddess Parvati herself worshiped and pleased Sri Swasthani to get married to Mahadeva (Lord Shiva). The Vratakatha cites this phenomenon many times to convince the sufferers that their salvages lie in the vratas and worships dedicated to Sri Swasthani. Aryan-Mongoloid interactions The Aryans are believed to have developed Sanatana dharma, the righteous way of life, long before entering Bharatavarsha. But legends indicate that they confronted the Mongoloids, and after some interactions they recognized Shiva as Mahadeva, one of the major Trios of the Godhead. Two clues hint at Shiva being a Mongoloid. Firstly, Shiva is worshiped as Kiranteshwar Mahadeva, Kirants being a Mongoloid ethnic group. Second, the abode of Shiva is in Mount Kailash, an area from where some Mongoloids are believed to have come to Nepal. Historically, from the southern flanks of the snow-capped mountain ranges—the Hindu Kush to the Himalayas—formed interfaces where the Aryans met the Mongoloids. This is demonstrated by Dakshaprajapati’s objection to marrying off eldest daughter Satidevi to Mahadeva (Lord Shiva) as Shiva was ‘far inferior’ to other deities his daughters were married to. Not only social interactions but also deep acceptance of each other had developed between the Aryans and the Mongoloids. There was deep friendship between the Aryan Vishnu and the Mongoloid Shiva (Mahadeva). Desirous of marrying Satidevi but being rejected by her father Daksha, Mahadeva visits Vishnu’s abode (Baikuntha) and asks the latter to act as a matchmaker. Vishnu promptly visits Daksha. Vishnu says he has come to beg for something, and he would express his desire only if the host promised to fulfill it. After Daksha’s affirmation, Vishnu expresses intent to marry Satidevi. Daksha unwillingly gives his nod, asking Vishnu to come with his kin and well-wishers on an auspicious day, and take Satidevi as his bride. Vishnu informs Mahadeva that the mission may succeed, although he himself had to ask for Satidevi’s hand. Vishnu instructs Mahadeva to appear as an old hermit at the time of Kanyadana (gifting of the girl), ask for alms and threaten to curse both the giver and the receiver if Kanyadana is proceeded without giving him alms. Vishnu would then explain the auspicious moment of Kanyadana would end soon and ask Mahadeva not to spell a curse, offer the alms after the Kanyadana and invite the latter to sit with him. At that very moment, Vishnu would play a trick and make Daksha put Satidevi’s hand into Mahadeva’s. Delighted, Mahadeva follows Vishnu’s words. The plan succeeds. Daksha gets angry but relents. Satidevi unhappily accepts Mahadeva in the guise of an old hermit as husband and follows him to Kailash. When Satidevi finds out that her hubby is one of the Trios of the Godhead, she begins to spend a happy conjugal life. Meanwhile, Dakshya is still angry with Mahadeva. One day, Satidevi sees her sisters accompanied by their hubbies flying in the sky and asks Mahadeva where those deities were going. Mahadeva tells her to ignore it all. Narada the great sage visits them and informs about Daksha’s Yagya where Deities, Yakshas, Gandharvas, Kinnaras, Daityas, Daanavas, Rishis like Vashishtha and Prabhriti, Naagas, Apsara and Dashadikpaalas were invited with their spouses. Narad wants to know why the couple were not invited, though they deserved to be at the Yagya. Satidevi, accompanied by Narada, rushes to her maternal home, pays respect to her parents and seeks to know why they had snubbed her and her hubby. As Daksha insults Mahadeva with words, Satidevi jumps into Yagyakund (where ritual fire is burning) and kills herself. Narada reports the tragedy to Mahadeva. This leads to a war between Mongoloid and Aryan armies. Death and destruction at the war and Mahadev’s sorrow over the death of his consort make for an epic that is a class apart.

Let Sri Swasthani bless us all

Today, Nepal is not only home to adherents of different religions; many Nepalis are atheist too. Even in old times, Nepal was diverse in terms of aspects like faith. In those days also, Nepal was constantly transforming, albeit slowly and naturally. In recent times, though, the demographics are changing quite fast, as a result of scientific outlook, down-to-earth materialistic social and economic relationships and our admiration of and submission to alien religions, cultures and languages, among others. Changes are so pervasive that it is sometimes very difficult to distinguish the new from the old. Historians agree that Nepal was once a confluence of two major streams of humanity–the Indo-Aryans and the Tibeto-Burmans—along with some other indigenous or roaming populations acting as contributaries. Over time, genetic mix-ups occurred also with other groups, along with new human-nature interactions in different ecological regions. Because of these mix-ups, communities considered to be of the Mongolian stock do not look exactly the same. Ditto with the Aryans from the hills and the southern plains. The Kumain Brahmins and the Purviya Brahmins have dissimilarities, too. While the two groups of Brahmins are considered to be the descendants of the same Rishis, sing the same Veda hymns, their rituals are not an exact copy of each other. While Nepal and North India have some common cultural and religious heritages, there are distinct practices that are unique to Nepal. Swasthani Bratakatha is one among them. The Sri Swasthani Bratakatha is a sacred scripture, a mini-purana if you will, where Kumara, the eldest son of Lord Shiva and Goddess Parvati, tells the story to the great sage Agastya. Kumara is another name for Skanda the great warrior, after whom there is the Skanda Purana, one of the 18 Puranas, part of the sacred literature of the Sanatan Dharma, of which Hinduism forms a part. The scripture mentions itself as part of Magha glories (Magha Mahima, the glory of the month of Magha) in the Kedarakhanda chapter of the Skanda Purana. Sri Swasthani is the local deity representing Goddess Parvati herself, addressed in the book as Sri Swasthani Mata (Mother Sri Swasthani). Vrata is a sort of religious penance, characterized by abstinence from some or all of the indulgence in food, water, sexual activity, arguments, speech, sleep, and desire. Katha means a story, here depicting the glory of Sri Swasthani. As with the Puranas and the Mahatmyas, the Swasthani devotees maintain bodily cleanliness, take minimal amounts of food considered pious, recite the Sri Swasthani Bratakatha and worship the Goddess Sri Swasthani for a month starting from the full moon called Swasthani Purnima. While one person reads out the story in the family, other people around the reader listen to the glory attentively and offer flowers, fruits, and holy water to Goddess Sri Swasthani. Devotees also flock to the Shali river in Sankhu for performing ablution and other rigorous rituals. A little bit about the nature of the Puranas, Mahatmyas and the Stotras (prayers), which are part of the ancient Sanskrit literature. Each of them sings the glory of the concerned deity, practice or tradition. The Ramayana upholds Lord Rama as the highest personality of the Godhead, Durga Saptashati sings the glory of Goddess Durga the Almighty Mother, and so on. While Brahma the Creator, Vishnu the Protector and Shiva the Destroyer are considered the Trinity, the Hindu scriptures list 10 major incarnations (including the Kalki, who, supposedly, is yet to be born) of God. The concept becomes more complicated with each reincarnation having multiple names. Vishnu alone has one thousand formal names, for example. Then each Bhakt (devotee) can give the Lord one or many names. Foes also give their choicest names to their ‘disliked’ Godhead. While showing a dislike for the Godhead in public, they may have high regards for the Godhead and even worship the latter in secret. This much about those deities, for now. In Nepali households, the recital of Shri Swasthani Vrata Katha by following prescribed rituals is believed to bring good luck, good health and prosperity in the family. Let Goddess Swasthani bless this one big family – the whole of Nepal.

Calculating Ukraine’s economic impact

The world seems to have entered a new crisis after the start of the Russian military action on Ukraine on 24 February 2022. While Russia has pushed itself in the war, the US-led NATO countries are fighting a proxy war.

The economy is a complex phenomenon, and thus linking it solely to one of the many wars and separating it from other natural and manmade events is difficult if not impossible. Yet I try.

The most obvious impact of the war can be seen in the hikes of fuel prices around the globe.

Ukraine has suffered the most. Once a strong oil, coal and natural gas producer, drilling wells and even nuclear facilities, Ukraine is under intense stress. Much of its capacity to operate and produce oil and gas has been lost. Despite a synchronization of the Ukraine and Moldova grids connecting Ukraine to the Continental European Grid, Ukraine faces electricity shortages as its nuclear facilities, hydro-power generation and a network of thermal plants can be attacked.

The EU heavily relies on Russia for energy. A 10-point EU plan envisions reducing its reliance on Russian energy by at least two-thirds. This would entail finding replacements for an average of 55 million cubic meters of gas a day.

The US has been trying to find a balance point that curtails the Russian economy but does not lead to a recession. The US supply covers over 50 percent of the EU’s and the UK’s additional LNG demand, and 37 percent of all LNG supplies into Europe. However, the US efforts, including the release of fuel from the Strategic Petroleum Reserves, have been unsuccessful. Also, the US and the UK have largely failed in getting additional oil from the OPEC countries.

Meanwhile, China and India have put their national interests first and have been buying Russian oil at cheaper rates. Under a new supply-deal, Russia will increase volumes by up to 10 billion cubic meters per annum from the Sakhalin Island in Russia’s Far East. Russian supply to China will exceed 48 billion cubic meter per year from 2025. India has looked to Russian oil as the latter began offering steep discounts of $35 a barrel—provided India does not cancel the existing 15 million barrels deal.

India, Taiwan, the Philippines, South Korea, Thailand and Vietnam are the largest importers of Russian fuel, all of whom import gas from the Sakhalin-2 and Yamal LNG pipelines. Having joined the sanctions, Japan is forced to seek alternatives from Australia, the US and regional supplies across Asia.

Russia’s position as a leading natural gas supplier to Europe and beyond had checked the proliferation of conflict on the European continent for two decades, to the benefit of all parties. But this time, the US-led opponents seem more tilted to prolong the conflict.

Russia and Ukraine are vital for the world’s food supply, and conflict between these two producers of basic staples has knock-on effects well beyond the front lines. Ukraine has been a major exporter of wheat, corn, barley and cooking oil in the three decades since the end of the Cold War. The former “breadbasket” of the Soviet Union, Ukraine had become a major source of sustenance for many other parts of the world. The war has cut deeply into both Ukraine’s production and its ability to export.

Supplies to the world from Russia, meanwhile, are being affected by both the international sanctions imposed on Moscow as well as by the war’s disruption of shipping routes.

Many countries face a supply crisis. Egypt and Lebanon rely on Ukraine and Russia for more than two-thirds of their wheat imports. In Thailand, close to a third of wheat imports come from Ukraine and Russia. Two-thirds of sunflower oil imports to Malaysia are also from Russia and Ukraine.

Food prices are rising fast. A World Bank index that tracks the cost of food is more than 80 percent higher compared to two years ago. Food prices are predicted to rise by 20 percent this year.

Directly affected poor countries cannot support small farmers in planting crops, which in turn could fill the gaps in the global system. They also cannot support the social safety nets to ensure access to food.

Turkey, Lebanon, Iraq and Somalia are highly reliant on Ukraine for food. The drought-hit countries in the Horn of Africa have experienced follow-on impacts, as they are missing grain from Ukraine, affecting countries such as Kenya, Tanzania, Rwanda, Uganda and particularly the Democratic Republic of Congo. Innocent Africans also have to bear the harms of climate change—food insecurity. Follow-on effects also hit Central America and South America.

Similarly, fertilizer supply has been disturbed. Farmers are not getting fertilizer in the planting season. India first increased its release of commodities into the global system. But as their harvests dropped, it began to prioritize its own food security.

WFP used to purchase half of its food from Ukraine. Buying in the global market costs 50 to 75 percent higher, reducing the number of people WFP can feed. If proper actions are not taken, as many as 100 to 150m more people are expected to go acutely hungry within a year.

Sri Lanka's economic collapse exemplifies how poorer countries are paying the price of Western sanctions on Russia. Sri Lanka is facing its worst financial crisis since its 1948 independence as it is unable to pay for basic imports and is crippled by domestic shortages of fuel, food and medicine.

The global economy is interlinked. Some parts of the world and some segments of population are more vulnerable. As the war prolongs and expands, all countries and peoples will be dragged into the conflict, and all will face economic crisis. Skyrocketing fuel and food prices have invited violent demonstrations in different parts of the world. Perhaps Sri Lankan President Ranil Wickremesinghe rightly says “…by the end of the year, you could see the impact in other countries”.

Nepal has seen unprecedented hikes in the prices of edible oils, petroleum, food grains, cereals, electrical and electronic appliances. The increase in transport costs has led to inflation. Interest rates have been increasing. Nepali rupee is depreciating against the US dollar. Set aside political issues for the moment; Nepal is trying to avoid a possible economic crisis.

What are Nepal’s priorities?

We must understand the reasons Nepal could, for ages, maintain a relatively stable economy, be free from colonization or occupation by foreign invaders, and provide home to one of the happiest people on earth. Throughout history, we Nepali have been strongly driven by the concepts of karma and afterlife (though both seem less of a priority today). Survival assured, people are willing to live on half of what they deserve. We are afraid of a poor public image, readily embrace austerity and try to save fortunes for the future. We are highly driven by cultural values.

Nepali are nature worshipers. We worship almost all things in nature: living and nonliving, terrestrial and heavenly, visible and invisible, plants, animals and humans, soil, water, air, fire and space, relatives and strangers. We consider anything that disturbs nature as problems: climate change, global warming, biodiversity loss, pollution of soil, water and air, radiation hazards, ozone layer depletion, and nuclear threat. In the face of terrorism and ongoing regional and global conflicts, not surprisingly Nepal had proposed itself a Zone of Peace!

Nepal needs both economic and infrastructure build-up to start from inside, from grassroots. Large-scale and high-sounding projects are not our priority. We do not want to inundate our millennia-old river-bank settlements to erect reservoirs for hydroelectricity plants. Instead, an average Nepali would prefer covering barren mountains with solar plates or wind fans.

The major part of Nepali agriculture is still organic. Ironically, we advocate productivity at any cost and teach farmers to use chemical fertilizers, pesticides, green houses, as well as exotic, hybrid and genetically modified (GM) and suicide seeds. Each of these steps makes the locals lose their independence and resilience to adversity. They inflict devastating harms on the locals, their livelihood, ecosystem and traditional wisdom. Overuse and inappropriate application of chemical fertilizers has upset soil composition and degraded its productivity.

Pesticides have not only indiscriminately killed insects, weeds, fungi, pests and other useful natural enemies of the harmful ones, they also have become serious threats to human health. They are now associated with various types of cancers, Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, organ failure and even sudden death. Seemingly attractive greenhouses have further damaged the environment. Imprudent adoption of exotic, hybrid and GM seeds has threatened our seed banks.

Throughout history, attached toilets were not our dream. Excreta was not tolerated in homes, or nearby water bodies or sacred places. However, the waste was commonly used as organic manure in the fields. After natural organic decomposition, the excreta mix and disappear into fertile soil. This fact was well understood by our ancestors. Human feces and urine formed a part of the healthy ecosystem. People benefitted from active toilet habits. Now we are encouraged to build modern, attached toilets, wasting our already scarce resources. The result is sedentary population, conflicts over dumping sites, as well as various other health and environmental hazards associated with improper waste disposal.

Rapid population growth has put extra pressure on arable land, housing, forest, open space, water and other natural resources. Population planning and maintenance of demographic balance should be a priority. However, our slogan ‘small family, happy family’ has been misinterpreted by many as ‘no to joint family’! The result is adults splitting up from their aging parents and aged grandparents, thus leaving the elderly at the mercy of the state and elderly-care centers.

Some people pay no heed to elderly in their families and localities but found or fund elderly care organizations elsewhere for publicity. Society needs to begin ridiculing such figures.

Our newly adopted education system that promotes materialist views oblivious of the spiritual, religious and moral aspects of development is no less responsible for social disintegration. Now each adult speaks of ‘I’ as ‘a free person’ with rights to choose a life ‘as I like’. With such stubborn views and attitudes, ‘we educated people’ have become feeling-less mechanistic living units, without any concern for the larger society. This has to change.

The biggest reason for our economic poverty is wrong land use. Nepal needs to learn from its own experience. Holding land as a fortune has many downsides. I do not propose snatching private land. But I do propose banning trade of land. Let us own no more land than what we can cultivate without hiring laborers or using mass production tools. Let us not own land or houses for rentals. Let us ensure skyscrapers are not blocking sunlight, or posing threat to bordering lands, houses or waters in case of fires or earthquakes. Such structures harm people both physically and mentally.

Let us begin anew. Let agricultural and settlement lands be fixed first. Let all rivers, streams and lakes and selected forests be declared sovereign—no government, no community, no person can remove them, destroy them, pollute them, cover them, or harm them. This will ensure clean air and environment. For industrial or other activities needing larger pieces of land, let the state or community rent land, hills, rivers, lakes or forests.

Let us fix land prices. Let the state buy all the land being sold, and sell it at the same price to those who need it, on a priority basis fixed by the local community. To the squatters, provide it for free but make it non-transferable and non-sellable, which the state can give to other people if the former tenants are no longer poor or cease to use land as required by the contract.

We also have other development needs. The above-mentioned steps will not only make our land more inhabitable and ensure better and healthy food supply. They will also save our precious resources and enable us work on other priority projects.

The author is a professor of pharmacy at Tribhuvan University

Bilateral solutions for Nepal’s trade imbalance

Being landlocked between two large countries, Nepal’s international trade has been basically limited to China and India. With the end of the Rana regime and opening up to the world, Nepal’s trade diversification began in 1951. In his seminal article “Nepal’s Recent Trade Policy” published in Asian Survey in 1964, YP Pant describes how Nepal’s favorable trade with India before 1951 had turned to a deficit. Nepal’s trade volume with Pakistan (including the present-day Bangladesh) accounted for less than three percent of the total. Pant also mentioned that Nepal’s trade with Tibet was negligible.

With the construction of the Kathmandu-Lhasa Highway and other land routes, China became our second largest trade partner, today covering 14 percent of total foreign trade. India remains our major trade partner, making for 64 percent of total trade. Nepal has active transit treaties with India, Bangladesh and China. Again, our trade is basically limited to India and China.

What is bothersome is Nepal’s trade deficit, which hit $11.69bn in 2020-21. Nepal exports to India a tenth of what it imports from there. With China, while Nepal’s import was $1.95 billion in 2020-21, our export was a negligible $8.35 million. In the first six months of the current fiscal, the balance of payment (BoP) was at a loss of $2bn. Such huge trade deficits and negative BoP can herald an economic failure. Immediate attention is called for.

Compensating such huge deficits with tourism, which brought Nepal total revenue of $668 million in 2019, is unrealistic. Remittance too is declining. The demography of Nepali workers overseas is changing, with an increase in the number of skilled workers who are going to more advanced countries and regions, and choosing to settle there. They are less likely to send remittances to Nepal where they do not intend to live. Nepal is thus yet to find an effective way to balance its trade.

Failing regionalism

Multilateral trade forums, including the WTO, have emerged as a solution to trade barriers, promising coordinated trade negotiations that enable smaller economies to get fair terms. Regional negotiations also help member countries avoid double standards in dealing with different neighbors of similar cooperation potentials.

Simplification of multilateral cooperation definitely facilitates trades. Unfortunately, not all member countries and regions can make equal gains. Multilateral cooperation helps those who prove competitive in global trade, and hinders the relatively weak and disadvantaged.

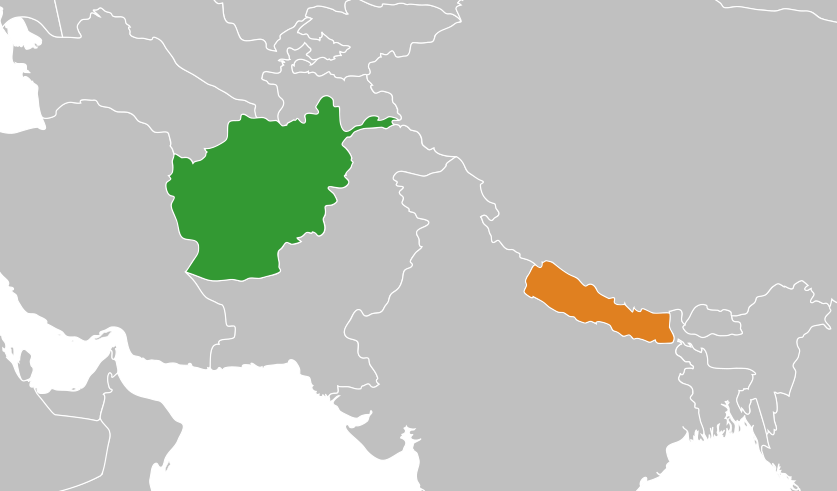

What Nepal needs is to identify geographical and economic regions, membership in which gives it an opportunity to carry business more fairly. At present there is little scope of regional trade cooperation with the north as it is difficult for cargos to get past the vast, neighboring China. South Asia is where Nepal belongs, which is also why it helped establish the South Asian Free Trade Area (SAFTA)—with Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka as its signatories.

Nepal also joined the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC) in 2004 whose priority areas include trade and investment, and tourism. Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Myanmar, Nepal, Sri Lanka and Thailand are members of the BIMSTEC Free Trade Area. However, our economic and trade cooperation has been basically limited to India.

Not that there is no possibility of meaningful cooperation within SAFTA or BIMSTEC. With Indian help, there are already signs of trade in products and services like electricity, agricultural products, information technology, medicine, tourism and education. However, compared to India and China, trade volumes with other countries are small, and any trade surplus with them is unlikely to offset the deficits with India and China.

Go bilateral

Nepal’s efforts at Nepal-China-India trilateral cooperation have not been successful. China and India share a long land border, and are also connected with seas. The Chinese land connected to Nepal is sparsely populated, and has limited scope for trade other than in minerals, and Indian pilgrimage to Mount Kailash and Mansarovar. Connectivity alone will not bring Nepal substantial economic gains. Further, long-term rivalry between China and India is not conducive to trilateral cooperation.

India, which maintains a porous, open border with Nepal, frequently sets conditions to imports from Nepal. India says its favorable terms of term only extend to goods and services originating in Nepal, and exclude the goods and services where foreign raw material or investment is involved.

Nepal is a minor trade partner for both China and India. But, for us, they are major ones. Here, economic and trade diplomacy could be useful. First, we should classify our trade items into essential and non-essential. We should then allow import of non-essential commodities, provided such imports do not lead to bilateral trade imbalance. Second, we should request China and India to invest in Nepal in sectors that contribute to import substitution, and promote our export to the investing country or to other markets outside our reserved quota.

Third, we should listen to their suggestions on bilateral trade balance, and try to accommodate them so long as such measures do not negatively affect Nepali economy, jobs, social harmony, culture, values, politics and international relations.

Sure, some items we import from our neighbors are refined third-country raw materials, or are in short supply here. Such items can be considered essential, and thus should be excluded in the evaluation of bilateral trade balance. These items as well as security-related and life-saving goods and services and new essential technologies can be covered through donations, remittance and international cooperation.

With right decisions and modest austerity, we can become self-sufficient in food and basic services. Outside these, Nepal should adopt a policy of balanced bilateral trade.

The author is a professor of pharmacy at Tribhuvan University

Opinion | Dealing with new Afghanistan, a Nepali perspective

Sooner or later Nepal has to come to a working relationship with the Taliban-led Afghanistan. There are more factors linking these two countries than those dividing them. Both are landlocked. Both are members of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), the UN, and the IMF. Both have joined the China-led Belt and Road Initiatives, and are observer members of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. Both nations are trying to come out of messy conflicts, discard the ‘least developed’ label and achieve ‘developing’ status.

Politically, Nepal has embraced a socialism-oriented, secular multiparty democracy. As a signatory to a series of human rights treaties, and as a UN member, Nepal is bound to promote universal respect for and observance of, human rights and fundamental freedoms of all without distinction as to the race, sex, language or religion.

The new Taliban regime of Afghanistan has said the country will be ruled under the Islamic sharia law. Nepal maintains a friendly relation with Afghanistan, and is unlikely to bother with its internal affairs. We should indeed respect the religious, political and economic choices of Afghan people.

In the broader spectrum, Nepal is itself a country sandwiched between two giants with different political and economic systems. It needs to use its limited strength and influence prudently. Protecting national sovereignty, safeguarding interests of Nepali nationals, providing reasonable support to Nepali blood, languages, cultures, identity and history, both inside and outside the current political borders, are our primary duties. Afghan people and big powers among them will solve the issues of human rights, counter-terrorism, and other conflicts associated with values there.

In terms of political maps, sometimes united and sometimes divided, Nepal has remained an independent, sovereign country. Even if outsiders have settled in Nepal and ruled it, they have ultimately been assimilated to the Nepali soil, their off-springs becoming dhartiputra or the children of the land. A key to our success was articulated by our founding father Prithvi Narayan Shah who suggested Nepal maintain good relations with China and India.

The land of present-day Afghanistan has been invaded and ruled by different forces in history. It was conquered by Darius I of Babylonia circa 500 BC, Alexander the Great of Macedonia in 329 BC, Mahmud of Ghazni in the 11th century, and Genghis Khan in the 13th century. Even after Afghanistan was created as a nation in 1747 by Ahmad Shah Durrani, through a series of wars in the 19th century, it was forced to cede much of its territory and autonomy to Britain. Afghanistan gained full independence from British influence only in 1919.

Following the British withdrawal from India in 1947, Afghanistan had to handle a largely uncontrollable border with the newly-formed Pakistan. Afghanistan and the Soviet Union became close allies in 1956, followed by Afghan reforms the next year, allowing women to attend university and join the workforce.

Conflicts and internal fights led to the 1979 Soviet invasion and the 1989 withdrawal; the 2001 US invasion and the 2021 withdrawal. Located at the strategic crossroads of Central Asia, South Asia and West Asia, Afghanistan has been a battleground of different political, religious, cultural and economic powers throughout history. So far all attempts to occupy Afghanistan have ultimately failed.

The effects of the American counter-terrorism campaign since 9/11 have not been uniform. In countries such as Saudi Arabia, UAE and Qatar where the US did not seek regime change, the US efforts have been a success. In countries such as Syria, Iran, Afghanistan and Iraq where the US focused on regime changes, the US efforts have failed to contain.

The terrorists have succeeded in identifying themselves as the forces fighting the US and other anti-Islam countries and forces, and thus winning Muslim sympathy worldwide. Besides, the hidden American geopolitical interests helped blur the differences between moderate Muslims and hardliners, many a time tagging moderates as hardliners, which ultimately led to the spread of terrorism.

Also read: China-South Asia cooperation: Sky’s the limit

Americans first tried to use the Islam element to counter the Soviets. After the downfall of the Soviet Union, this trained militia turned on the US, their former mentors. As such, it is not a confrontation between two civilizations; it is not a West-versus-Muslims clash. It is a confrontation between two interest groups to dominate the world, the resources. The US being the stronger one adopted the role of the ‘world police’. The Muslim outfits being the weaker side tried to present themselves as ‘Muslim fighters’ to challenge the US, in the form of modern guerrilla attacks.

Following the US withdrawal, the world is divided on tackling Afghanistan. The US and its allies have refused to formally recognize the Taliban-led government. But China, Russia, Pakistan and some others have maintained relations with the new regime, some hoping the Taliban will help counter cross-border terrorism, contain radical Islamist ISIS group and respect the rights of women and minorities.

What should Nepal do?

Nepali people and media seem divided on the Afghan issue. Some have expressed worries that extremists have come to power; others are happy that the US occupation has ended. This scribe would rather recommend a careful, weighted response.

Nepal has an open border with India. Unlike China and the US, we are unable to control the border effectively. Not far back, Rohingya refugees from Burma, some Afghan refugees, and even Congolese refugees, have successfully made their way to Kathmandu. So tightening of the land border, especially in cooperation with India, should be our top priority. Similarly, we should beef up scrutiny against suspicious international arrivals by air.

As to maintaining our relation with the Afghan regime, we should raise issues of our interest. It was the Taliban that demolished the two monumental fifth century Buddha statues in Afghanistan's Bamiyan Valley in 2001. The fanatics did not pay any heed to the worldwide condemnation of their cultural crime. Buddha is a part of our history, our identity and Nepal is the mother of Hinduism, Buddhism and related language and culture. We should talk about these issues openly. Our foreign policy should reflect our interests in a broader sense.

Opinion | Burdened with books

We as a society barely ask a basic question, what are schools and books for? To help students adjust in the competitive and dynamic society? Or, to model them into our social frame? Perhaps, for both. For simplicity, let us not indulge in defining different but related jargons—education, teaching/learning, literacy, curricula, aims, objectives, outcomes, achievements, ethics and the like.

Schools are considered essential. State, society and parents invest in them, trust them with training young minds. The governments designate ministries, bureaus, councils or departments to take care of the schools (‘school’ here includes all levels and categories of institutions providing education or training). These designated governmental bodies, schools and communities develop and implement the modalities, contents and other details. Students are rarely involved in decision-making; most parents are considered unknowledgeable and required to oblige to what the system offers. Both the parents and children are helpless when the system does not allow the student’s promotion to next grade for his failure to achieve minimum competency in a language that is not his own!

Besides what the students are being taught and how they are being helped, the weight the students have to carry in the form of books, stationery and other supplies is alarming. A grade seven Nepali student weighing 29 kg carries an average burden of 6.5 kg as a schoolbag, 8.5 kg if the melodica is included. Even kindergarteners have to carry bags! While the majority of kids in urban areas either have access to school bus or are helped by guardians, those in remote countryside have to carry the load themselves, walking up and down the hills and sometimes crossing rivers on the way.

Also read: Systemic dysfunction

The detrimental effects of disproportionate bag weights are clear. A 1994 Scandinavian Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine article based on studies in 1,178 school children in France discussed musculoskeletal problems (lumber, thoracic and leg pains) associated with backpack use, which has become an increasing concern with school children. A 2005 Applied Ergonomics article found as many as 77 percent of secondary school students in New Zealand experienced musculoskeletal symptoms, including upper and lower back pains, due to their heavy school bags.

Indian students suffered no less. As Awantika and Shalini Agrawal report in International Journal of Research (2015), most of the 10-13 year-old students in Lucknow, India, felt pain from carrying a bag comparable to pain from physiological stress.

The 2006 Children School Bags (Limitation on Weight) Bill passed by the Indian Rajya Sabha asked the government to ensure that there would be no school bag for a child studying in nursery and Kindergarten. For children in other grades, the weight of the school bag should be no more than 10 percent of body weight. The law, never implemented, would have made the schools violating the rules liable for a fine of up to three lakh Indian rupees.

As pressure builds, regulations and policies limiting the weight of school bags are finding space in India, which also addressed this issue in its National Educational Policy, 2020. It suggests the weight of a school bag for students between grades 1-10 should be no more than 10 percent of their body weight. Now onwards, Indian schools are required to keep a digital weighing machine inside school premises and monitor the weight of school bags on a regular basis.

What makes the bag heavy?

First, ignorance and a misguided mentality. Schools, the sources of ‘light’ are full of ignorance. They act as if the volume of books their students carry reflect the education, skills, discipline, wisdom and creativity they impart; it is comparable to their majestic-looking, fearful, English, ‘suit and tie’ culture aimed at mercilessly collecting high education fees from poor parents who make the payments hoping their kids will escape the hardships they were forced to bear. Misguidedly, parents and kids do not complain against the bulging of the school bags.

Second, profit motives. The indirect, mean, greedy intentions of those promoting the sales of such books become visible if the whole of business is seen in detail. Consumerism is encouraged; no, it is injected, in the book market. Even if the curriculum remains the same, the publishers revise the textbooks, although they know such revisions are cosmetic, just to ensure the students cannot use old books. They want to add both the number and volume of books.

Also read: Fond memories of my grandfather and Dashains past

Third, the bookworm culture. For centuries, learning and memorization of vocabulary, mathematics, classical grammar, facts and figures formed the bulk of school education. It was the best way to educate students in a mostly illiterate society. Now that most of our population has become literate, the bookworm culture should be replaced with a system more conducive to the building of a harmonious society, one which sows creativity in pupils and prepares them to cope with an unseen future.

Recently introduced computers and internet should not (and have not) replaced printed books, but unfortunately, these have added to the burden in the sense that the pupils are asked to prepare and print so called ‘project reports’ and ‘powerpoint presentations’ on this and that topic, which the kids prepare with the help of the Wikipedia and guardians.

Fourth, unnecessary homework. Schools and parents don’t realize that children need free time, time for physical activities and entertainment, and time to communicate with family members and friends. Students in lower grades should not be given homework at all; for them, learning should be a game, a pleasure. Students in higher grades can be given limited assignments, just enough to encourage their independent learning, no more.

Fifth, lack of lockable drawers for students. Letting students leave their heavy books in the classroom would help reduce their burden. Schools should provide such facilities.

The author is a professor of pharmacy at Tribhuvan University