Baburam Bhattarai’s ‘Hinduphobia’

It is difficult to imagine Dr Baburam Bhattarai, PhD looking up to the disgraced former US President Donald Trump for inspiration. There is little in common there. So it was bizarre that Bhattarai would steal a trick from Trump's social media playbook: share a meme, consequences be damned.

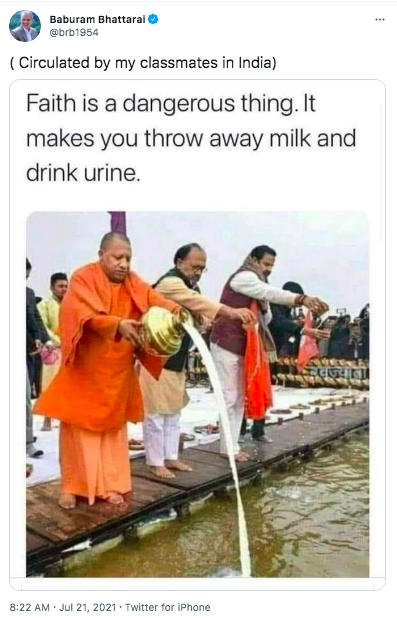

In a strange attempt to charm his 1.3 million followers on Twitter, Bhattarai posted a meme that shows a saffron-clad Yogi Adityanath, current Chief Minister of India's Uttar Pradesh state, pouring milk into a body of water. Above the picture, the words read, “Faith is a dangerous thing. It makes you throw away the milk and drink urine.” The joke didn't land. Not many were laughing. I found it embarrassing.

The meme would be hard to justify had a common Twitter troll posted it. It's inexcusable for a former prime minister and a public intellectual at that. Why Bhattarai decides to insult the chief minister of an Indian state with which Nepal shares deep social and economic relations is difficult to explain. This at a time when Nepal-India relations are in a possible upswing (the Dharchula incident hadn't yet happened). It is a recipe for an unnecessary diplomatic row. And what an embarrassment it would be too! Could the current government, so reliant on India for political, economic, and medical support, afford this sideshow?

A liberal reader might be inclined to forgive Dactor Sahab had he criticized Adityanath on the Indian government’s delay in sending vaccines to Nepal. Or even Yogi's comments about the role of religion in this country. Or his past rhetoric about other faiths. But this is not what the good doctor chose to do. Instead, he criticized Yogi for performing a simple act of faith, of offering milk as an act of worship. Something millions of Hindus humbly do every day.

The meme wasn't a criticism of the role of Hinduism in politics. This wasn't Raghuji Panta criticizing KP Oli's attempts to seek Pashupatinath's favors to improve his political fortunes. This wasn't women invoking Sita to make valid points about the patriarchy in our society. There was no broader political message. The meme's point was the insult of Hindus, and the problematic reference to drinking urine brings this home. Bhattarai can't, and to my knowledge hasn't attempted to, say— he’s ignorant about how this caricature is constantly deployed to dehumanize Hindus—including in countries where they are persecuted.

That his stance wasn't moral or universal was obvious. Barely two hours after this tweet against the danger of faith, he politely wished the Muslim community a happy Eid-Ul-Adha. He raised no objections. He gave no lectures. He made no insults.

But let's not let this chance provided by Bhattarai's gaffe go to waste. This tweet is an opportunity to begin a conversation about the term "Hinduphobia." This relatively new term hasn't yet found currency in Nepali politics but is increasingly adopted in the Tweeter-verse. In April this year, the Hindu Students Council (HSC) at Rutgers University in the US hosted an academic conference entitled "Understanding Hinduphobia." Given that this was the first conference on the subject, the purpose of the meeting was pretty broad. And the working definition they've given is equally comprehensive: "Hinduphobia is a set of antagonistic, destructive, and derogatory attitudes and behaviors towards Sanatana Dharma (Hinduism) and Hindus that may manifest as prejudice, fear, or hatred. Hinduphobic rhetoric reduces the entirety of Sanatana Dharma to a rigid, oppressive, and regressive tradition."

It's noteworthy that academics and not political or cultural groups led the conference. Also important is the venue. Rutgers University has become center stage between Hindus who assert that Hinduphobia is a pernicious and targeted form of bigotry and critics who claim Hinduphobia is a myth propagated by the Hindu Right to suppress valid criticism of Hindutva and intimidate people into silence.

Bhattarai’s tweet doesn't do the critics of the term "Hinduphobia" any favors. His meme does reduce "the entirety of Sanatana Dharma to a rigid, oppressive, and regressive tradition." It is particularly telling that this comes from an ex-communist, now socialist, former prime minister.

Bhattarai ought to know better. As a veteran politician, he should know sentiments and style matter in politics, both domestically and internationally. Whatever his version of Make Nepal Great Again, it won't be achieved by intentionally insulting 80 percent of this country's population. Or is he of the belief that insulting Hindus has no political or electoral consequences? If so, the narrative that Hindus are a political force in Nepal is widely overblown.

Trash talk like this hampers constructive public discourse and ultimately weakens the foundations on which we ought to build our republic. An idea for which Bhattarai himself and millions of Nepalis with him have sacrificed much and lost many.

Personally, it was the sly manner with which he framed the meme that struck a particular nerve. In the text box attached to the meme, Bhattarai wrote, "(Circulated by my classmates in India)." What cowardice! A feeble attempt to seem brave for sharing the meme while simultaneously seeking a cover behind friends. This too was straight out of Trump's playbook: always have an escape route, and when things go wrong, blame it on friends.

Slok Gyawali is a writer based in Portland, Oregon

Decolonizing museums, repatriating Nepali heritage

At this point, it is hard to be surprised when stolen objects from Nepal are found in museums in the West. Art historians and academics have altered us about the theft for decades now. And yet this past year has been different. Stories of repatriation to Nepal have only been outpaced by stories of web-savvy Nepalis locating yet more stolen objects in collections abroad.

More objects being found, sustained media focus, decent government responsiveness, and museums willing to at least acknowledge the problem. So what’s different? Why is there such a sense of indignation when activists find one more object in a foreign museum? And what might the current focus tell us about building and sustaining a movement to keep pressure on museums and the Nepali government to ensure Nepal's heritage is returned to its people?

The murder of George Floyd reignited the conversation on race relations. The Black Lives Matter protests brought home the frustrations against the enduring legacy of white supremacy. It is to this movement that the renewed conversation of repatriation of Nepal’s stolen objects owes a partial debt. The movement towards racial justice in the West opened the space to critically examine the role of museums in feeding a culture that fetishizes other people and their faith.

At first, a surge in finding so much of our heritage looted and displayed abroad is horrifying, yet ultimately this is a necessary and welcome step. At a time when there is little Nepalis agree on, it's almost exhilarating to find an issue about which we are on the same page. As in any healthy public sphere, we might disagree on the details—Who should lead the charge? How do we secure the idols from going missing again? What objects should we prioritize? But by and large the janta now speaks with one voice: We want our heritage back!

There is, however, the occasional troll who will argue that these objects are safer in the West and therefore should remain in foreign lands. But such self-deprecating arguments can be safely ignored. It would be like allowing bankers to rob people and invest the money because they are better money managers.

In situ picture of the Uma Maheshwara, taken from Lain Singh Bangdel's ‘Stolen Images of Nepal’

Besides tapping into this specific socio-cultural moment in the West there are more obvious and inward-looking reasons that have allowed for a surge in finding our heritage abroad.

The groundwork for current efforts was put in place by giants like Lain Singh Bangdel, Jürgen Schick and Ulrich Von Schroeder. They collected and published photographic evidence of objects in situ, in their original place, which is essential to any claim for repatriation. This is a huge asset when asserting Nepal’s claims. Building on this foundation, digitization efforts like the Global Nepali Museum, the Huntington Archive, and the Remembering the Lost projects have democratized this data. This in turn has allowed researchers, professionals, and amateurs alike to dig into provenance history and compare museum photos with in situ objects.

Nepali social media can be a vicious space. Abuse galore. But ever so often Nepali Twitter bands together to amplify issues that encourage a national sense of self. And this is an important reason why the groundbreaking research done by Twitter handles like the Lost Art of Nepal are able to reach thousands of people across the globe, especially when English and Nepali journalists pick up the story.

It is also encouraging that the state—the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Department of Archeology, local governments, and concerned embassies—have been fairly responsive and make official inquiries as follow-ups to news of objects' rediscovery. The recent announcement by the DoA that they have completed the paperwork required to begin the repatriation process for 26 objects in the UK and France is highly encouraging. We hope to see this being expanded to include objects discovered in the MET, Art Institute of Chicago, and the Denver Art Museum.

This moment of global reckoning with colonial history has emphasized the need to question the arrogant concepts of “encyclopedic” and “universal” museums. Collections filled with objects stolen from other communities don’t make for very inclusive educational institutions.

Across the globe formally colonized people are asking for what is rightfully theirs. Nepal is no exception. The aphorism “Nepal was never colonized” is a double-edged sword. It reasserts an important part of history while simultaneously distorting it. Nepal cannot shy away from articulating its assertions in terms of the larger narrative around decolonization because “we weren’t colonized”. True, but that’s a gross misunderstanding of how cultural imperialism works. And it is simply a bad strategy.

Nepal and Nepalis should absolutely engage in and interpret socio-cultural moments in the West that allow it to act on its own interests. We ought to reassert ourselves as a shaper of the global conversation on this issue, rather than being mere recipients of it.

Having navigated the age of imperialism in relative isolation, Nepal entered the age of decolonization unsure of its role and place. Compared even to our neighborhood, we were poorer and far-worse educated, and with less interaction with the outside world. When it did open its borders in the 1950s people and ideas—of “progress”, “civility”, and development”—rushed in. In this new world, indigenous episteme—a system of understanding—was challenged and dismantled, from those outsides and those within. It has taken us a few decades to come to grips with it.

Nepal in 2021 is different. Compared to any other time in our history, Nepalis are more literate, more tech-savvy and there are simply more of us around—at home and abroad. That access to knowledge is leading more Nepali to ask questions about their history. Why were objects of reverence so discourteously taken away and housed in museums? How did we get here? And who allowed it? This questioning of the past is welcome.

Nepalis, when empowered with the right tools, are able and willing to fight to have their heritage returned to them. But success will depend on how we organize and articulate our sense of loss and assertions.

The Portland, Oregon-based author is co-founder of the Nepal Pride Project