Multiple readings, multiple meanings: A book review

“The House on Mango Street”, a 1984 novel by Sandra Cisneros, is a short book. It’s written in short bursts, with small chapters, some of which are barely a page long. That is probably what draws me to the book time and again. I know I can finish it in a day and move on. But every time I pick it up, I’m also hoping to get something more out of this little book that’s sold millions of copies, made its way into different prescribed syllabi, and is considered a modern classic. And it doesn’t disappoint. Each reading leaves me feeling a little different from how I did before.

Partly based on Cisneros’s own experience, The House on Mango Street is the story of Esperanza Cordero, a 12-year-old Chicana girl growing up in the Hispanic quarter of Chicago. The story explores what it’s like belonging to a low economic class family and living in a patriarchal community besides also dealing with elements of class, race, identity, gender, and sexuality.

_20210209121830.jpeg)

At the start of the book, you find out Esperanza and her family have arrived on Mango Street. Before coming to Mango Street, they had moved a lot—from one run-down building to another—always promising themselves that they would own the next place and that it would be their ‘dream house’. The house on Mango Street is finally theirs but it’s far from the home they had always dreamt of.

Though the place is a lot better than any of the previous homes they have lived in, Esperanza isn’t happy. She pines for a ‘real’ house with a big garden and everything else she has seen in ‘ideal’ houses on TV. The rest of the story is basically Esperanza’s growing-up years in the house as she writes poetry to express her suppressed feelings, makes friends who aren’t really friends, and tries to craft a better life for herself.

I can understand the universal appeal of this book and why it’s prescribed reading in many countries. A story of a girl transforming through the challenges she faces as she steps into her teenage is motivating. With Esperanza, Cisneros has also delved into the immigrant experience and difficulties that children and young adults face as they struggle to fit in when they find themselves in unfamiliar surroundings. The only problem I have and what’s perhaps a bit jarring for me is the book’s narrative structure. It can get a bit confusing at times and you find yourself rereading certain parts because they have gone over your head.

But despite its length, A House on Mango Street feels like a full-fledged novel and that’s the beauty of it. You will feel like you have known the titular character for a really long time because, a) there is just so much happening in the story, and b) with her intriguing thoughts and feelings, Esperanza takes up a lot of space in your head and heart. You can also relate a lot with her because some struggles—feeling like you don’t belong, trying to change yourself and your situation—are universal.

Fiction

The House on Mango Street

Sandra Cisneros

Published: 1991

Publisher: Vintage

Language: English

Pages: 110, Paperback

Elevation: Among the first of my Kings: A book review

I have never been a fan of the horror genre—in both books and movies. I know friends and YouTubers who love reading/watching horror. They have always made it sound so fascinating. There is a booktuber (@paperbackdreams) whose fondness for horror is particularly palpable. She gets visibly excited and happy while taking about the horror books she has enjoyed. I love watching her videos and hearing her talk about all these scary stories. But somehow being scared, with goosebumps up my arms, wasn’t a state of being I was comfortable with.

That changed when I started watching movies based on Stephen King’s novels on Netflix during the lockdown. The movies were creepy and made me cover my eyes and ears at least a dozen times during our weekly movie night—but I was hooked. Now, I seek horror recommendations and I’m determined to discover writers other than King who will make my skin crawl. Turns out, that ‘goosebumps up your spine’ is a pretty fun feeling.

I’ve also kind of made it my mission to devour King’s books; the endings of many of his movies, I hear, are quite different from how the books conclude. Not satisfied with how some movies have ended, I figured I’d read ‘The Shining’ and ‘Pet Sematary’ to get some closure. But, unfortunately, I couldn’t find the books at any of the bookstores in Kathmandu and the only one I could lay my hands on was ‘Elevation’.

Elevation is a tale of Scott Carey and how he ends up uniting his town folks, while dealing with a baffling personal issue and his own prejudices as well as those of his community. It’s a story of an ordinary man, in extraordinary circumstances, who chooses to rise above hatred and value the people in his life.

Scott is suffering from a mysterious ailment. He is losing weight but doesn’t look any different. Every day he is getting lighter and lighter while taking up the same amount of space he always did. He doesn’t know what will happen if he steadily keeps losing weight. Scott also has another problem. He is engaged in a low-key battle with one of his neighbors, who happen to be a lesbian couple—Deidre McComb and Missy Donaldson. He is sure Deidre’s dog is doing its business on his lawn. She refuses to believe it and so he is fixated in proving her wrong.

Generally, King’s books can be used as doorstoppers. Not that we should use books for that but you get the drift. Elevation, on the other hand, is a novella. And it’s not horror. As disappointing as that was when I read the blurb, the book is now one of my favorites. It’s unlike King’s regular style but he is a skillful storyteller and, turns out, he doesn’t need the help of horror to grip your heart.

Elevation is a charming tale of the way our biases run deep, why it’s important to get over our narrow-mindedness, and how we can find friendship and love in the unlikeliest of places.

Fiction

Elevation

Stephen King

Published: 2019

Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton

Language: English

Pages: 132, Paperback

A Very, Very Bad Thing: All about acceptance: A book review

In the past few years, we have definitely made some progress on LGBT issues, with many countries legalizing same-sex marriage and guaranteeing them equal rights. But it’s one thing to have laws and mandates in paper and quite another to have them followed. In conservative societies, people’s attitude to gays and lesbians isn’t going to change just because homosexuality isn’t a punishable offense anymore.

This is where stories can help. Fiction, I believe, makes us empathetic. It exposes us to a horde of characters and experiences that we otherwise wouldn’t have come across. A good story can put things in perspective and instigate change. ‘A Very, Very Bad Thing’ by Jeffery Self is, in that regard, an important book. The YA novel is short, has a simple premise and forces us to confront our hidden biases.

Marley, the 17-year-old protagonist, introduces himself as a “snarky gay kid from Winston-Salem, North Carolina, watching life through the disconnected Instagram filter of my generation and judging every minute of it.” With supportive parents and an equally snarky and cynical best friend, Audrey, he seems to be getting on just fine. Then Marley meets Christopher and it’s love at first sight—for both of them.

But Christopher’s father is the famed televangelist Reverend Jim Anderson who is actually tied to a movement called “pray-the-gay-away”. He and his wife have tried everything to “fix” Christopher and they aren’t ever going to give up. There is no question of accepting Christopher for who he is.

The story is basically about these two gay boys trying to be themselves and enjoy life a little in a hostile environment. It's also an apt depiction of how societal constraints can sometimes lead to mistakes and mishaps that can never be set right.

Ever since I read A Very, Very Bad Thing, I’ve been wanting to recommend it to everyone I meet—avid readers, occasional readers, and even those who have to be coaxed or challenged into reading. Stories like these are imperative to make us understand that every person has a preference that isn’t necessarily governed by how they were born, and that every person should be allowed to live the life they want.

When I was at the bookstore, I randomly picked up A Very, Very Bad Thing and read the blurb out loud. A staff who had come to chat with me made a disgusted face and told me I’d be better off not reading “things like that”. It wouldn’t be a stretch to say that her reaction is still how majority of public feel about LGBT in Nepal. Many will behave like they understand and accept homosexuality but it’s just a façade. It’s important to change people’s mindset for real so that the world becomes a safer, more loving space for our children. A Very, Very Bad Thing and stories like that are crucial in bringing about the radical transformation we desperately need.

Fiction

A Very, Very Bad Thing

Jeffery Self

Published: 2017

Publisher: Push, an imprint of Scholastic Inc. Publishers

Language: English

Pages: 225, Hardcover

The Archer: Nothing new

Let me get this out of the way: I’m not a Paulo Coelho fan. ‘The Alchemist’, which seems to find its place in almost everyone’s list of favorites, isn’t a book I’m crazy about. But there are some Coelho books, like ‘Veronica Decides to Die’ and ‘Eleven Minutes’, that I must admit I enjoyed. Still, Coelho, whose books have sold 300 million copies in print, isn’t an author I recommend or get excited about.

I bought ‘The Archer’ entirely because it’s a slim book. I’m trying to read a book a day this January just to give myself a pat on the back at the end of the month and feel like my life is headed somewhere as I continue to work from home. Also, flipping through the book at Ekta Bookstore in Thapathali, Kathmandu, I realized I could enjoy the illustrations even if I didn’t particularly like the book (and I didn’t think I would) and could justify spending money on it.

The Archer begins with the arrival of a stranger who says that the local carpenter, Tetsuya, is the best archer in the country. He challenges Tetsuya to a contest. Though Tetsuya hasn’t picked up his bow and arrow for years, he agrees and then goes on to perform better than the stranger. A young boy is witness to all this and wants to learn the ‘way of the bow’. Tetsuya relents on the condition that the boy never reveals his true identity. The rest of the book is basically a series of motivational dictums where archery is used as a metaphor for life lived well.

It took me about 45 minutes to read The Archer and more than half of that time was probably spent gazing at the illustrations. Unsurprisingly, I didn’t like it that much but there are bits and pieces that aren’t bad. The ‘life’ advice was a little too much in-your-face and it did sound repetitive at times. But, I feel, we must embrace whatever ideas we can get on how to live a balanced and harmonious life. Yes, such advice comes our way all too often, from ‘well-meaning’ people, but if it gets you to try and improve your life even a little bit, it’s perhaps worth enduring these not-so-gentle reminders.

However, I would not encourage people to read the absolutely mundane stuff that Coelho seems to come up with. I have met people who believe if Coelho gets non-readers reading, then there’s really no harm in that. I disagree because I think we are dumbing down our senses by consuming words that don’t do anything other than make the author rich.

So, if you must, read The Archer once. Borrow the book. Find a free e-book or the audio version. See what kind of mindset it leaves you in. But please, please don’t let Coelho ever dictate how you think or set the tone of your reading life.

Fiction

The Archer

Paulo Coelho

Illustrations by Christoph Niemann

Translated into English by Margaret Jull Costa

Published: 2003

Publisher: Viking

Pages: 130, Hardcover

A great book of ideas

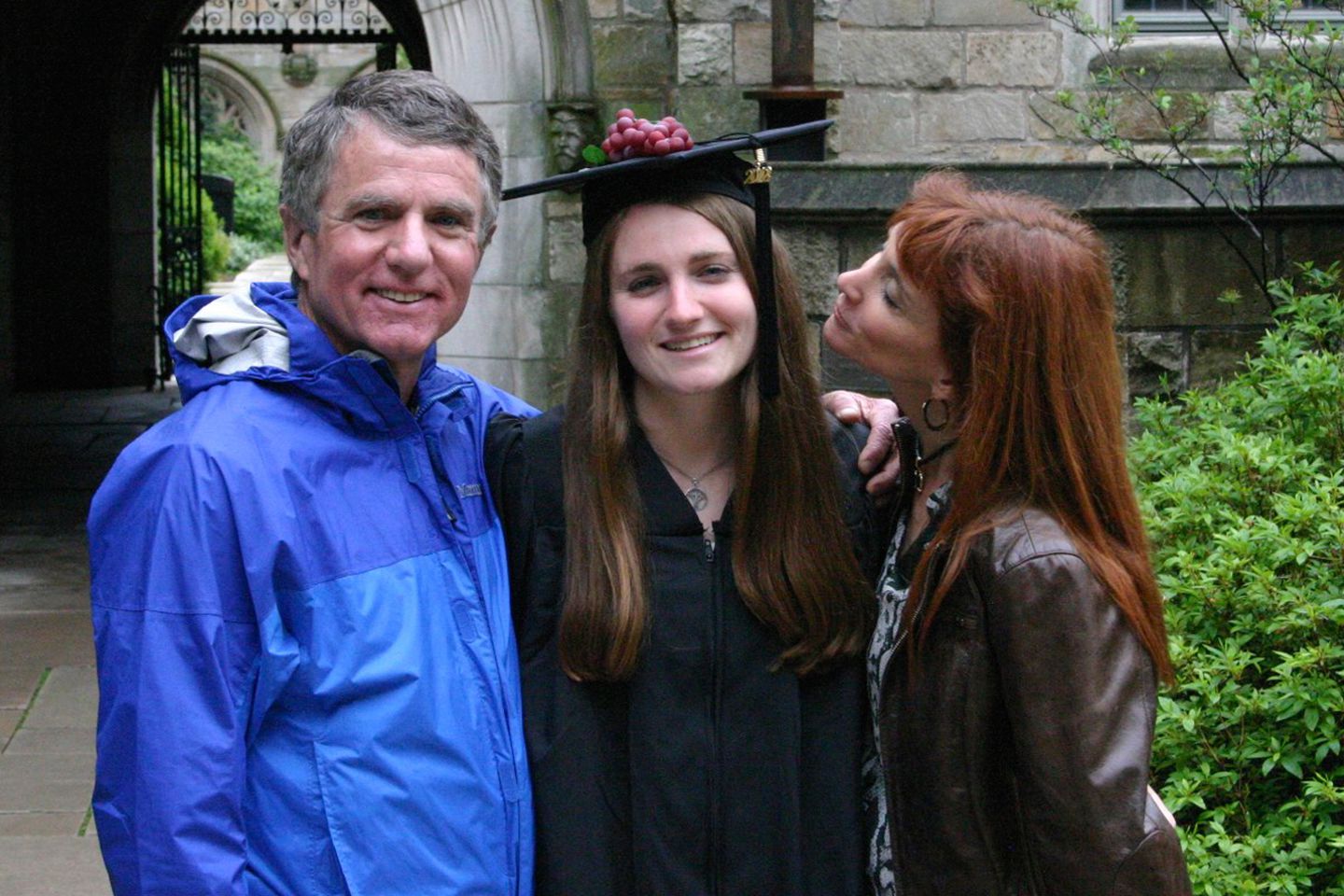

Winner of the Goodreads Choice Awards Non-Fiction 2014, ‘The Opposite of Loneliness’ by Marina Keegan is a collection of essays and stories that captures the universal hopes and struggles as one prepares to face the ‘real’ world after graduation. On her graduation day Marina had said, “I will live for love and the rest will take care of itself.” Her love for and fascination with life is evident in each one of the 18 essays and stories in this collection.

Marina died five days after graduating magna cum laude from Yale in May 2012. Her boyfriend, who was neither intoxicated nor speeding, fell asleep at the wheel. The car hit a guardrail and rolled over twice, killing Marina but leaving the driver unhurt. Her parents, Tracy and Kevin Keegan, wanted the state to drop the charges of vehicular homicide against her boyfriend because ‘it would break Marina’s heart’. When he went to court, they stood by his side and the case was dismissed.

Marina’s dream—after hearing novelist Mark Helprin say, during a master’s tea at Yale, that it was virtually impossible to make a living as a writer today—was to become a writer and ‘stop the death of literature’. Published posthumously with the joint effort of her professors, friends, and parents, The Opposite of Loneliness is all that the world will ever get to hear from Marina. It’s unfortunate because Marina, it seems, was a gifted writer. Her essays and stories draw you in and you find yourself tuning the rest of the world out.

What made the book compelling, for me, was definitely her writing that’s laced with humor. She doesn’t hesitate to make fun of herself and she does so with an enviable ease. In a way that helps you try and accept your own idiosyncrasies a little more. Her writing is also emotional and contemplative, thus forcing you to look at things from different perspectives. An important underlying message of much of her work is that it’s never too late to live a life with joy and meaning. We could all use a little reminder every now and then, couldn’t we?

The Opposite of Loneliness might not be writing at its finest but Marina’s voice is fresh and unpretentious. She wasn’t trying to sound a certain way or writing to impress. Reading her makes you feel she loved to write and so she did with reckless abandon. That makes it even harder to read her but you know, deep down, that hers is a book you will be recommending and revisiting as often as you can.

Essays & Stories

The Opposite of Loneliness

Marina Keegan

Published: 2014

Publisher: Simon & Schuster

Language: English

Pages: 208, Paperback

A Bollywood movie-like book

Does the world need one more sappy Bollywood romance? Probably not. But is Bollywood still going to come up with silly love stories that have nothing new to offer and are rehashes of what we have already seen a gazillion times? Most definitely. These films will have you rolling your eyes at their mediocrity but you will still be dragged to them like a moth to a flame.

The same holds true for books based on Indian love stories. There are plenty of those out there but the publishing industry keeps coming up with new ones because they know those who like romance will lap them up. (We are a gullible lot.)

‘The Marriage Game’ by Sara Desai is basically a love story of a ‘dashing’ boy (who has unresolved issues) and a ‘beautiful’ girl (who is oblivious to the fact that she’s gorgeous). They initially hate each other and then invariably fall in love. Because, really, isn’t that what happens in real life all the time? Throw in a complication or two and a horde of annoying, supportive, loud relatives and The Marriage Game is your regular Dharma Productions or Yash Raj film.

Here, Desai introduces us to Layla Patel who returns home, from New York, to her family in San Francisco after her boyfriend cheats on her and she is fired from her job. Her dad offers her a chance to make a fresh start and lets her use the space above their family restaurant to set up her own recruitment business. He has leased the space to a corporate downsizing company but he tells her he will take care of it. But he has a heart attack before he’s able to sort things out.

Enters Sam Mehta who pretty much falls in love with Layla at first sight. But things are, of course, far from easy, with Layla having given up on love, Sam’s guilt about not being able to protect his sister from her abusive husband (and thus failing his parents as a son), and the two fighting over who rightfully owns the office space.

I bought the book because it had a nice cover. I hadn’t even read the blurb. What could go wrong with a book that pretty, I thought. It’s not that I was disappointed by the story. For those of us who grew up on a steady diet of Shah Rukh Khan’s romances, The Marriage Game brings about a strong sense of déjà vu. As predictable and common as the story is, you can’t give up on it because you, thanks to voyeuristic tendencies, want to know how the story reaches its inevitable end.

But Desai’s writing is tedious and the characters aren’t convincing. You feel nothing for Layla and Sam. The jokes don’t make you laugh—they sometimes elicit a chuckle at best. Reading The Marriage Game feels very much like watching a movie. You can literally see the scenes unfolding before your eyes. This book was apparently one of Oprah Magazine’s Most Anticipated Romances of 2020 and though I can’t, for the love of life, understand why, I enjoyed it while it lasted. It’s a fun book to pick up if you want something light to read while sipping on a gin and tonic on a bright sunny afternoon. But if you want a good read, then don’t be swayed by the lovely cover and spend your money on something else.

Fiction

The Marriage Game

Sara Desai

Published: 2020

Publisher: Berkley

Language: English

Pages: 338, Paperback

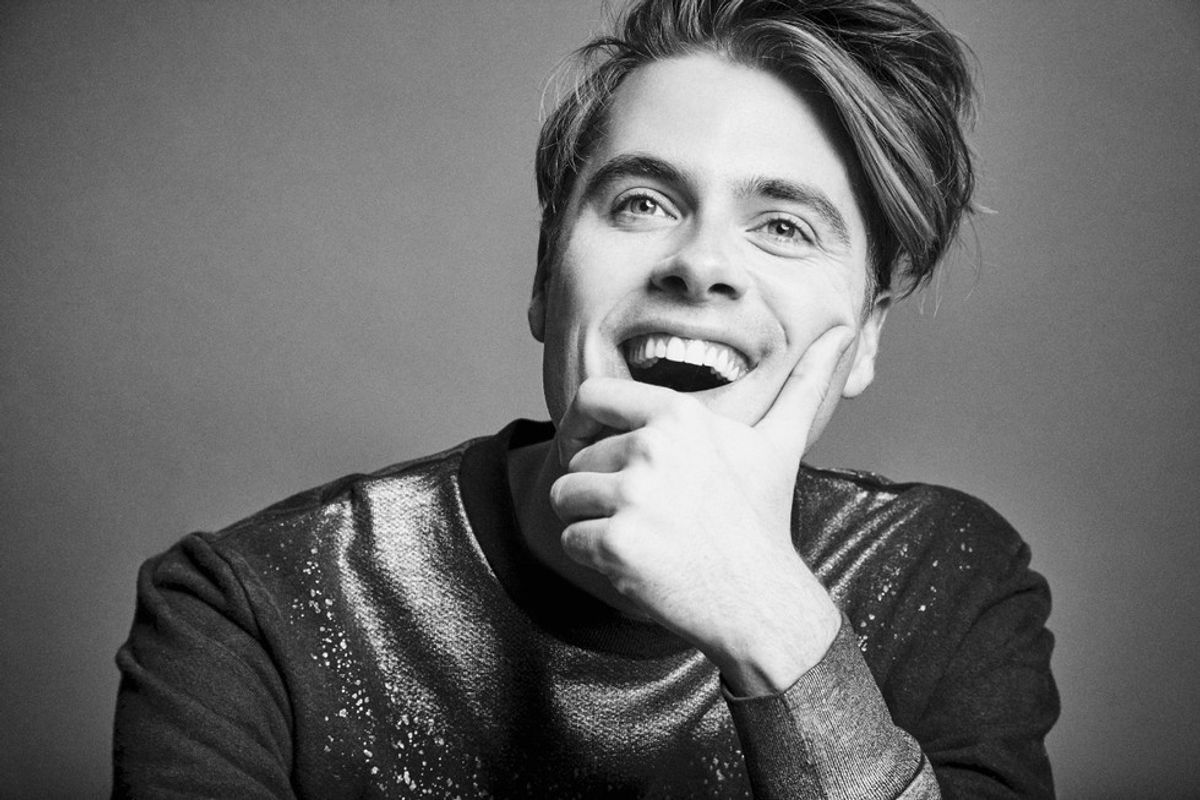

My best book of 2020

‘The Midnight Library’ by Matt Haig is the best book I read in 2020. And in 2020, l read a lot of books—as many of you under house arrest (read: lockdown) might have. It’s simply the most beautiful book I’ve ever read. I feel like I might have said that about quite a few books (‘A Man Called Ove’ by Fredrick Backman and ‘Revenge’ by Yoko Ogawa, for instance). But then isn’t that how a great book is supposed to make you feel? Like you haven’t read anything as spectacular in your entire life and that this book is the one that will stay on top of your recommendation list forever.

The Midnight Library is about a girl named Nora Seed who feels trapped in her life. She doesn’t have any close friends, her work doesn’t excite her, and she clearly lacks a purpose in life. And then her cat, Voltaire, dies and she’s fired from her job. Nora feels incapable of doing anything right, and unwanted and unloved. After all, she couldn’t even look after a cat. What hope, really, is there for her?

So, without a solid reason to continue living, she decides to end her life. When she wakes up, it is midnight and she is in a ‘library’ of sorts. The library, with tall pillars and stone façade, is apparently a place between life and death. The books in the library are all different versions of Nora’s life. Each book she picks gives Nora a chance to try out another life. Mrs Elm, Nora’s high school librarian who she used to play chess with, is the guardian of this library and she helps Nora find the ‘perfect’ life she is looking for.

We all have regrets; things we wish we had done differently or opportunities we hadn’t let pass. We find ourselves wondering how our lives would have turned out if we had, say, started saving since high school, cultivated better relationships, or chosen a different career. Our natural tendency is to always want what we don’t have and, as a result, we aren’t as happy as we would like to be. This book makes us rethink our values, see the beauty in little things, and be grateful for what we have.

What I really liked about The Midnight Library, apart from the vignettes of Nora’s different lives and Haig’s simple, smooth prose, is how it makes you contemplate your own life and reevaluate how each of your successes as well as failures have shaped you. I was forced to look at events that I always wished I could undo as experiences that have led to many good things in my life today. Reading the book made me celebrate life and be thankful for all its quirks.

The Midnight Library made me happy, revel in the ordinary, and value everything I have a whole lot more. It is, perhaps, everything I have ever wished for in a book.

Fiction

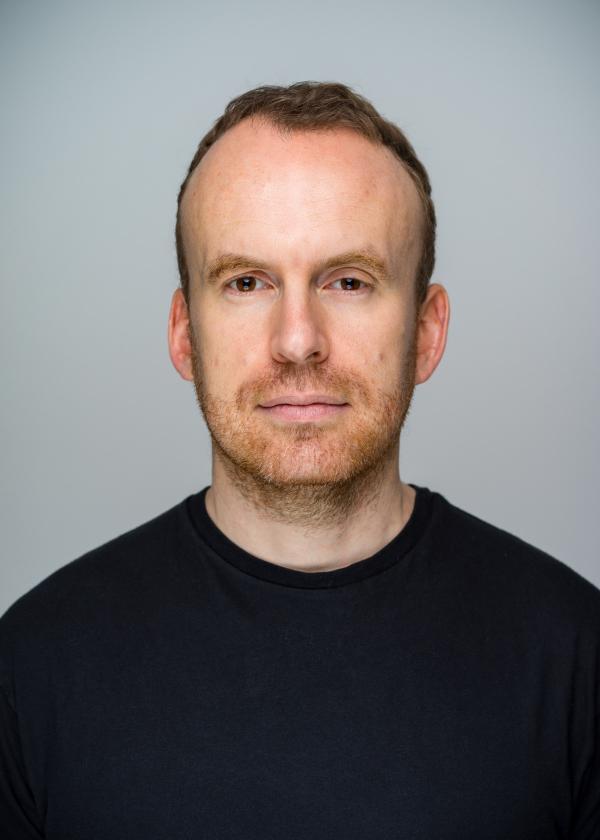

The Midnight Library

Matt Haig

Published: 2020

Publisher: Canongate Books Ltd

Language: English

Pages: 288, Paperback

Contemplations on life: A book review

Margaret Atwood is one of the world’s most acclaimed writers. She is a novelist, poet, essayist as well as short story writer who has won numerous awards and accolades. Though mainly known for her novels—especially ‘The Handmaid’s Tale’ that was made into a television series, and its 2019 sequel, ‘The Testaments’, which won the Booker Prize—you’d be missing out if you didn’t read her poetry collections. I’m not a big fan of poetry but Atwood’s poems strike a chord and make me think.

As Atwood herself puts it, “Poetry deals with the core of human existence: life, death, renewal, change; as well as fairness and unfairness, injustice and sometimes justice. The world in all its variety.” “Dearly” is Atwood’s 12th poetry collection but her first in over a decade.

Dedicated to her long-time partner Canadian novelist Graeme Gibson who died in 2019, Dearly is a collection of poems that celebrate life. Many of the pieces were apparently written in anticipation of Gibson’s death. He was suffering from dementia.

The poems in the anthology were penned over a period of 10 years, between 2008 and 2019. In the introduction, Atwood says she stored the poems in the drawer, and then when she felt she had enough (to publish), took them out and separated them into sections.

These are poems about memories, loss, ageing and endings, and new beginnings. They are also about everyday objects, routine, and birds and animals. You will also stumble upon love poems about zombies and tributes to women who have been raped and murdered.

The common thread is that all these poems make you reconsider your beliefs and ideas. In fact, there is something about Atwood’s writing that makes you do that—go into this zone from where things look a whole lot different.

Reading Dearly also makes you pay attention to the nature around you as Atwood describes the environment around her, in her hometown in Canada. These poems, inevitably, make you think of the challenges the world faces today—mostly the environmental degradation that we have let go unchecked.

Yet there are also poems you struggle to make sense of. Some don’t really communicate what you feel they are trying to convey. But you still find yourself going back to them to pick up clues you might have missed. That’s the power of Atwood’s writing. She is brilliant at evoking vivid imagery and her poetry is as fine as her prose, if not finer. All in all, Dearly is a sensitive understanding of what makes us human and the way Atwood describes the world makes you fall in love with it a little more.

Poetry

Dearly

Margaret Atwood

Published: 2020

Publisher: Chatto & Windus

Language: English

Pages: 124, Hardcover