The tech-glorification complex

As locusts descended on Gurgaon, India, I watched videos online and realized the area noted for its technological sophistication and prowess looked like an ecological desert. The blue-glassed skyscrapers, asphalted treeless roads, barren streetscapes so different from green rural landscapes of India struck me with their ecological unsoundness. While touted as a “Smart City,” filled with smart people using and selling smart tech, what was most obvious was how helpless the people were in warding off this natural disaster. They had no ducks, no sparrows, no wasps, no schoolchildren picking locusts off the ground to sell to the local government for Rs 25, even. They did not even have soil they could apply with nitrogen fertilizer, another deterrent to locusts.

Yet we’ve been forced to think this way of living is the acme of perfection, one we should all emulate and aspire to. Bill Gates raised $9 billion to create a vaccine for Covid 19. Why did all the nations of the world eagerly handover their health budgets to this tech marketer, instead of banding together to create an international consortium of researchers from universities around the world which they could depend on to deliver for the public good? Why did they believe that the richest man in the world, with many pharmaceutical investments, was the right man for the job?

The trendy term STEM seamlessly fuses science with technology. Science, which has always meant gathering of knowledge through observation, and conclusions based on rational correlations, doesn’t require a techie twin to become science. With the STEM worldview, however, we have started to assume that all of our knowledge depends not on long and thoughtful observation, but on technological machines which define the contemporary scientific encounter. If there’s no machine to contextualize the phenomena, surely it cannot be science!

A few days ago, I had to call a fridge repairman to refill my fridge with hydrocarbon gas. As he stood there among the copper tubes and wires, cutting and fusing things with his blowtorch, filling my kitchen with toxic gases, it occurred to me that this was a futile, convoluted exercise. Who came up with this idea of creating this giant machinery held together with wires, tubes and gases, simply so that people could keep their food cold for a day or two? We were willing to blow a hole through the ozone for this enterprise and kill all of life in the process. What leap of logic made us think that this invention (designed by men who’d never tried to clean a plastic ice-cube tray, for one) had to be in everyone’s kitchen?

The ventilator, which fills people up with oxygen, operates on a similar premise: the body is a big complicated machine, one we must refill with gas when it runs out of it. It is no surprise that the dials with which a fridge repairman fills up a gas chamber is similar to the dials which regulate oxygen in a ventilator. This mechanistic view is a Western way of looking at the body. X-ray, ultrasound and other imaging devices peer into the body to understand its workings. The body is to be repaired by being cut, drilled, blowtorched by chemicals and radiation. We glorify the technology behind these procedures. We are told these apparatuses are the height of scientific thinking, not a rather crude way to approach the complex workings of a body with an unknowable mind.

A recent discussion I got into Twitter with a young woman illustrates this point. A young baby was left tragically deformed by doctors at Grande Hospital after they used suctions to mechanically pull water from his brain. Babies in Nepal are traditionally massaged with mustard oil to avoid this very problem of inflammation and water collecting in the brain. Fenugreek is a known anti-inflammatory agent. The Tamang woman who shaped my nephew’s head did it beautifully. I had sat and watched the way she patted the baby’s head into shape.

Knowing I was straying into sensitive territory, but pushed by the thought of the young child, I made the point that the tragic latrogenic distortion of Rihan’s head could be corrected by age-old traditional mustard oil massage, because the two halves of the skull would not fuse till he was three. There was still time to reshape it through the gentle, expressive molding skills of the masseuses who know so well how to improve upon nature’s work. A young woman responded to me in this manner:

“i dont even want to argue w you. pls refrain from peddling pseudoscience on everything under the sun.”

Why do we believe that “science” is somehow wedded to this mechanistic view of the high-tech world, and anything else which does not involve technological apparatuses, Big Pharma, transnational corporations, or Western Latin phrases, is not science? Why has technology become our touchstone of scientific knowledge, not rational and patient observation? Why did we just hand over $9 billion to a tech guy to cure ourselves, when that work should be done by an international consortium of researchers coming from Third World countries where the coronavirus hasn’t spread, and whose traditional science and knowledge have already provided the cure?

America’s crimes against humanity

Fifty-four African nations have called on UN Human Rights Council to have an urgent debate on police brutality and racially inspired human rights violations. The letter asks for the debate to be held next week.

The militarization of the police and imprisonment of African-Americans go back to slavery. White supremacy—the notion of white culture being supreme over others—is part of the hegemonic cultural narrative of the US. This narrative has enabled militarized violence over minority groups, including Native Americans and Latinos.

Black Lives Matter has opened the door. The UN should now open an extended investigation into America’s crimes against humanity. Since the end of the Second World War, the deep state and military-industrial complex of the US has terrorized the globe. From Afghanistan to Iraq, Cambodia to Laos, the same logic of white supremacy and economic and technological domination has led to the deaths of millions. Cuba, Iran and North Korea suffer and starve under the US economic sanctions.

America has been implicated in the conflicts in the Gulf, the Middle East and Africa, with mercenary troops and friendly nations acting as fronts for proxy wars.

Agencies such as the CIA have carried out assassinations and torture. But the CIA is a known institution. More sinister are the covert agencies whose purposes are unknown, conducting scientific experiments with no ethical guidelines.

Scientists are already capable of wiring up people’s brains to computers, with the purpose of downloading thoughts. If mobilized against opponents, this technology would bring about perpetual slavery through mind-control. This is a violation of bodily integrity that even the slaveholders of the 18th century could not have imagined. And yet Elon Musk’s Neuralink is a reality, celebrated as a tech “innovation” that will change the world. The inherent fascistic nature of the tech-industrial complex has done little to harm him or other tech magnates. Tesla’s stocks continue to rise exponentially behind smoke and mirrors of Wall Street. We are made to think of this as a social good, not the acme of the fascist panopticon.

In April 2015, the Large Hadron Collider, based in CERN, Geneva, “accelerated protons to the fastest speed ever attained on Earth,” Symmetry Magazine reported. Superconducting magnets were involved, 6.5 TeV of energy was generated. At the same time, a powerful quake shook Nepal, killing 10,000, injuring 22,000 (me amongst them), and making 400,000 homeless. America contributed $531 million to the Large Hadron Collider project. Around 1,700 American scientists worked on the LHC research, more than any other nation’s, says CERN’s website. These two events are connected. This is not a matter to be dismissed as “conspiracy theory,” although that strategy has worked brilliantly in the past. Now the time has come for careful legal investigation through the auspices of international institutions.

All these crimes against humanity were enabled by the propaganda of the US as a human rights defender, a fierce supporter of democracy, and a beacon of freedom. None of this is true. Democratic regimes were removed via coups and brutal military dictatorships put in their places, as in Latin America. The true purpose was to remove indigenous people from their land and have that land be taken over by multinational corporations of America.

America has used China’s state violence against Uighurs to protest the dangers of Chinese fascism. While chilling, it doesn’t compare to what America is doing. One million Uyghurs are incarcerated in Xinjiang re-education camps. “In 2014, African Americans constituted 2.3 million, or 34 percent, of the total 6.8 million correctional population,” says the NAACP’s criminal justice fact sheet.

With Black Lives Matter mass protests, the world has spoken: the racialized violence of the American state must end.

African-Americans face the possibility of being choked, electro-shocked or killed as they go about their lives. A white policeman can kill a black man or woman, in their own homes or while going about their daily business, at any time.

We have no idea how many times this same kind of impunity has played out internationally, in deserts of Afghanistan and darkened streets of Iraq with no cameras present. How many people have the Americans killed, covertly and overtly, with technology as yet un-explicated in law books? How many people has it driven to suicide?

America’s narrative of its own ethical goodness has silenced all opposition. An institution as aware of international law as the UN sees no legal doorway to the crimes against humanity committed by the American troops, agents and covert institutions over 75 years. Now the time has come to take apart that myth. The UN must work together to put every single war crimes criminal before the long arm of the law. It is time for the trial of the century to start.

Famine or feast in Nepal?

Kathmandu saw its first known starvation death last week: Surya Bahadur Tamang, who’d spent several decades hauling goods in Kathmandu, was found dead on the sidewalks of Kirtipur. He did not make enough money to rent a room for himself, so he slept on the streets. On Saturday, May 23, exactly two months after the lockdown started and all work shut down, he was found dead, still clutching the woven jute strap he used to carry loads on his back. The locals said he had no family. He’d been eating free food offered by local organizations. Yet that wasn’t enough to ward off starvation.

How many people have died already is up for debate: on Twitter, there was news of at least one other man who had died of hunger in the Tarai, news which went unreported in the national media. These are not isolated incidents but a systematic failure of justice. As time passes and the lockdown continues, there will be more starvation deaths.

In a 2017 report by the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), almost two million people in Nepal were considered undernourished. Nepalis living in remote mountain areas had less access to food than those in the Tarai.

The government of Nepal has made no plans to feed the estimated 10-15 percent of the population—two million undernourished, plus 1.5 to potentially three million migrants who have returned from various cities of India—who already faces hunger.

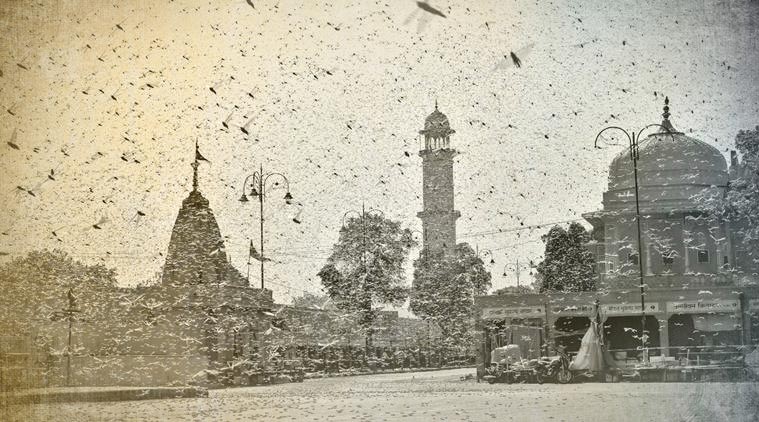

On top of the lack of government preparation, we have a locust infestation, which has moved up from Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh to Uttar Pradesh, just across Nepal’s border. The FAO estimates that the locust invasion will grow bigger by June-July, with the advent of wet weather and the monsoon. We could potentially lose much of our major crops. Coupled with this is a border dispute with India, which could again trigger a blockade similar to the one in 2015. There will be less food export to rely upon as the locusts destroy essential crops and cause food shortages within India.

The Nepal government is still focused on developing immediate response plans for the Covid-19 pandemic. The primary focus so far has been managing the health sector and implementing the lockdown. As days turn into weeks and weeks turn into months, there is an urgent need to also focus on other crisis that will compound the risks from Covid-19. The most immediate threat is famine.

Many countries have started rethinking their food trade and food security status. If countries like India and China do not keep trade open and supply chains working, food security risks for Nepal could be devastating. It is therefore of utmost importance to start discussing the importance of local food production and food sovereignty for Nepal.

The returning migrant workers, who are now only viewed as a health risk, could be Nepal’s opportunity to win back our own food self-sufficiency. There are vast tracks of empty land in the hills and mountains and even Tarai. Out-migration and labor shortage was one of the reasons for abandoned cultivable land. Therefore, we need to capitalize on this opportunity and direct the returning labor force into farming. Nepal has deep roots in agriculture, and most of our young people already know how to farm. What they need to get started is government support for seeds, fertilizers, tools, and markets.

Local governments could provide support by making land leasing easier so that ownership rights are protected but the land is not left unplanted. Water management technology, seeds fertilizers and other inputs are needed as well. The government must also set up farmer co-ops to link farmers to larger rural and urban markets. The actual approach will need to be managed at a local level. There is no single silver bullet approach. This also gives the local governments an opportunity to demonstrate their prowess.

In Germany, when farmers needed extra help to harvest some spring crops that usually relied on migrant laborers from Eastern Europe, students from universities volunteered to help. The universities were closed due to the Covid-19 and farmers even paid the students so it was a win-win situation. The context in Nepal would be different, but we need to find a way to increase our agricultural production. We cannot leave our lands barren and simply wait for the crisis to slowly unfold. Action needs to be taken now to hire students for agricultural work, to subsidize and support women farmers, and startup farmer co-ops.

Also urgent is the need to prepare for a locust invasion. While chemical sprays can keep the most immediate swarms at bay, they may harm other beneficial insects, so we should also think about biological control of the pests. Wasps are known to be natural predators of locusts. We could ask Netherlands, which has top-notch biological pest control expertise, for help with designing an integrated pest management solution. We can also use drones as well as airplanes which can fly down towards the swarms and disperse them with noise. Scientists have shown the locusts stop swarming when there’s a lot of noise.

We should not let this crisis go to waste. Let us use this opportunity to build back our food sovereignty. What we decide to do now will determine whether we face famine or feast in the upcoming winter.

Nepal’s lockdown reality check

A few nights ago, I heard a young child talking with a man outside my lane. The voice of the child was rough, like she was from the villages and hadn’t been educated. The man was laughing occasionally in the casual manner of the laborers who still lived in the giant big building that has been constructed in front of our house as an investment property. Built for $600,000, it is now empty, with no renters coming forward to pay the rumored 10 lakh rupees per room. But a group of young male workers are still living there, no doubt guarding the property. Every evening, I hear beautiful flute music from the same building. But this evening, I heard the voice of an angry young woman who was coercing the child to do something she didn’t want to. The child started to cry hysterically. The man laughed. Then they left.

I have done research in Mumbai and I know child prostitution runs beneath the layers of Nepali society, where family members and guardians often become the enablers of sexual exploitation. While I cannot say with certainty that is what occurred near my house, it disturbed me tremendously. How many women and children are now at the mercy of predatory men, with the income earned from casual, informal work having come crashing down?

The government of Nepal, unlike Western countries, has no social safety net that can protect teenage girls and children. They have no provisions for women who are now out of work—the five kilos of rice, some dal and a few packets of cooking oil can barely meet the needs of women with young children. A young woman who was helping me to clean my kitchen decided it wasn’t worth her while to stand in line at the ward office for this small amount of food.

“Who wants to wait in line for five kilos?” she said, dismissively. Then she said they would ask for nagarikta, and she’d have to go back to her village to get it. Later that week, I saw another woman in my neighborhood who I know has a young daughter become tremendously upset when she realized she’d need her citizenship to get the food being distributed—clearly she didn’t have it on hand.

Most pandemics of the past went on for 18 to 24 months, if not longer. It is likely that a famine as well as surge of coronavirus cases will follow in the autumn, as temperatures cool and food shortages become apparent. Yet does the government know how much grain we have in stock to feed 28 million people? Can it guarantee that it will have enough for the entire population from 23 September 2020 to 12 April 2022, which according to my (jyotish) calculations, will be the time of greatest death and despair? It may be 17 January 2023 before all deaths stop—that is when, according to jyotish, Saturn leaves Capricorn. Coincidentally—although according to jyotish there are no coincidences—Saturn, which rules death, dying, sickness, grief and despair, entered its own house Capricorn on 25 Jan 25, 2020. On 23 Jan, China shut down Wuhan, and on 30 Jan, the WHO declared a pandemic.

While traditional jyotish timing may not be used for government planning any longer, we can look at linear, Western history of pandemics and realize that deaths come in waves and that it rarely ends in a few months. What is our government’s exit strategy to support millions of young children, vulnerable women, unemployed disabled, and elderly? How will it give financial security to the young men and women in urban areas who are now trapped in their homes? What plans does it have to distribute food, vegetables, and medicines?

Provinces have set up systems to deliver old age-pensions, vegetables, and food to people right at their doorstep. Political representatives more accountable than those in Kathmandu hired buses with their own funds and came seeking for their villagers stranded in the capital, at a time when the sirsha netas had shut down the city with no provisions for people to return home. Thousands were forced to walk home for days, with kind people along the way offering them food and partial transport and in all likelihood saving their lives.

Kathmandu may be the capital city, but most of its local ward administrative units have been decimated by years of politicization, neglect, corruption, and non-accountability. The cellphone message saying, “If you suspect you have coronavirus, go to your local health center,” is a bit of a laugh in Kathmandu, because there are no government-funded local health centers, unless you are talking about the major hospitals. How many unemployed women with toddlers can walk to Shukraraj Hospital?

Perhaps the most chilling development in Kathmandu was seeing the video of little children being bathed in bleach before the local officials would give them free food. A global apparatus of authoritarianism, as epitomized by China, coupled with the bleach-can-heal wisdom of a “science is might and right” America, is squeezing vulnerable children and elderly all across the planet. In order to come out safely, we must resist both.

Cold West, Hot East

Despite ample evidence that the novel coronavirus has spread rapidly in rich, developed countries, and left poor countries unscathed, the WHO keeps up the official pretense that it will affect all countries equally. This, in fact, has shown not to be the case, after almost 3.5 months of global contagion.

If the scientific establishment were in the service of science (and not in the business of pushing forth the notion of European hegemony and supremacy, or marketing Big Pharma drugs), it would be asking the question: why? What factors are enabling the spread of this pulmonary disease in developed economies?

Several things stand out to me. First, the evidence that the coronavirus can survive for 72 hours on plastic. All economies devastated by the virus are plastic economies. People use plastic credit cards to pay for goods and services, they eat their takeout meals out of plastic food containers, and they buy their food from plastic bowls that have been touched by multiple hands on the chain of supply.

Second, despite the evidence, all health services have also pushed the notion that plastic is sanitary. Plastic is the only material from which PPE, which purportedly protects health workers, can be made. As you can surmise, this notion is problematic and may have led to many deaths of those at the health frontlines. The PPE may be infecting patients as well.

Third, rich economies rely heavily on refrigeration. Food which has been sitting for hours in a cooler is considered fit to take out and eat, without warming. As anyone in South Asia knows, anything that is not hot off the stove can harbor viruses and bacteria—we know this to our detriment from many cholera, diarrhea, and other seasonal epidemics tied to hygiene. Yet in developed economies this concern is waved off as a cultural superstition of Third World peoples. Surely, the much-vaunted civilized cities of the West are so much more advanced with their fridges and cold sandwiches?

There’s also the Asian notion that food that is cold in temperature can cause cold and flu. This is considered to be a quaint belief by the West, where ice-creams can be consumed in the middle of winter in swelteringly hot, central-heated restaurants. For Asians, cold comes not just through temperatures but certain foods considered cool/cold foods on the bodily temperature spectrum. Cucumbers and watermelons, for instance, are cooling foods, while ginger and chilly are warming foods.

This reminds me of the children’s game we used to play, where a blindfolded child has to find someone who’s hiding. He/she is taken around by another who says, “Cold, cold, cold” or “hot, hot, hot”, depending on how close the blindfolded seeker is to the hidden person they’re trying to find. “Cold” refers to “you’re off the mark.” “Hot” means “you’re very close.” Coronavirus control, it appears to me, could do with this childhood strategy—“Cold, cold, cold” and “you’re about to give yourself a cold with this chilly food”; and “hot, hot, hot” meaning “see all those Third World people who pressure-cook their food twice a day, do not eat out, and so far haven’t caught the flu? Yes, maybe it’s the hot food that’s keeping them alive!”

Fourth, in the countries where contagion is low or negligible there is no Amazon to distribute large numbers of plastic wrapped packages. Amazon has been in the news for several reasons—low paid workers, difficult work conditions, inability of workers to organize and ask for healthcare, lack of testing for Covid-19. There’s also a recent case in which a worker tested positive after Jeff Bezos visited the “fulfillment center.” These are perfect conditions for coronavirus infected workers to spread disease all across the country via niftily delivered packages.

Fifth, lack of well-equipped hospitals may in fact have been a boon in poor countries. A very high percentage of people who were intubated are dying after the procedure. Doctors have now gone on record saying that they misread the very low oxygen numbers and automatically put people on ventilators, not paying attention to the fact people were sitting up and talking despite low oxygen figures. The doctors have also said that the cases they see are more like altitude sickness, more than the normal kind of respiratory distress they were used to seeing.

One factor consistent amongst Third World economies: a reliance on herbal healing. Due to lack of big machines, most people in Third World countries know of a local remedy to cure respiratory problems. The Tibetan Government in Exile just handed out a black pill composed of nine herbs to its citizens—perhaps it is the first government to do so. India’s Ayush Ministry has been active online, advising people to take Ayurvedic remedies, including “golden milk”—a small teaspoon of turmeric with hot milk. Just as the rationalists (who are dropping like flies) give a disbelieving laugh, they should first do research on which system is winning the war here.

I would personally recommend garlic soup and timmur (Sichuan pepper) to people feeling unwell. Those two cured me of my altitude sickness when I got a pounding headache at Langtang, at 3,500 feet. If nothing else, the timmur will force oxygen into your lungs without the invasive presence of a ventilator.

Western medicine a boondoggle?

The WHO, among other authorities, has gone on record saying all “fake news” about coronavirus cures must be suppressed. The only true cure, it appears, is the Western medical establishment, with its resource-intensive hospitals, doctors and nurses, ICU beds and oxygen tanks, ventilators and intubation, N-95 masks and plastic face shields. Nothing else will do.

The modern hospital as an institution probably started in Europe during the plague of the 13th century, when monks in Christian monasteries put aside buildings in their premises to cure the sick. They also tended herbal gardens and grew their own medicinal plants, so they were ideally placed to cure those with life-threatening diseases. Due to their austere schedules and lifestyles, limited social contact with the outside world, as well as lack of sexual and physical contact due to vows of renunciation, it is possible they did not contract infectious diseases as easily as laypeople.

According to Wikipedia, “Towards the end of the 4th century, the ‘second medical revolution’ took place with the founding of the first Christian hospital in the eastern Byzantine Empire by Basil of Caesarea.” While ancient India, the Islamic world, Persia and others had their own hospitals—with the Islamic world specifically credited with systematizing the institution with departments, diseases, officer-in-charge, and specialists—it was the Christian notion of healing the sick which may have brought the institution to a wider population.

Hospitals were associated with various branches and sects of Christianity, all vying for power and prestige. The prestige of one’s sect depended on how well the narrative of medicinal power was projected and controlled. In keeping with the tradition of Christian dogma and persecution, those who professed disbelief were severely punished. Hospitals, cures, and associated medications all took on special mystique.

It is this history of medicine that is being played out now, in much the same manner, with people believing in the virtues of ventilators without a single critique (ventilators apparently have a low efficiency rate and can kill one-third of the elders after they are intubated, according to The New York Times). Plastic facemasks may or may not work, since the coronavirus can live for 72 hours on plastic. Even the whole idea of putting a large number of sick people together may be a failed experiment, since it is easy for those less sick to get more sick with more exposure to viral loads in a contaminated hospital environment, with people packed into a small space, breathing in huge amounts of viral spores through air-conditioners.

Ayurveda, India’s age-old traditional healing system, is promptly labeled as “fake” by this Eurocentric hegemonic model. BBC hastily put out an article to this effect, warning people that turmeric could not cure coronavirus. Prince Charles got caught up in the crosshairs, with an Ayurvedic Vaidya in Bangalore claiming, “Mr Charles is my patient.” The place put out a hasty rejoinder that Prince Charles had done nothing but take NHS advice. Turmeric, which may kill the virus faster than any known pharmaceutical in existence, has not been tested by a single scientist, despite there being evidence in plain sight with large parts of the “turmeric belt” of Asia and Africa relatively unscathed by the virus. Low contagion countries like India and many parts of Africa all cook their food in turmeric.

In addition, these countries also make low or no use of plastic food containers. Food is cooked daily, and nothing is stored for later. Despite hysteria about plastic being the one and only material that can shield people from the virus, it is pretty clear plastic is also much beloved by the virus as an elegant habitat. It survives for four hours on copper, but 72 hours on plastic.

All of this brings makes us question: Is Western medicine a giant boondoggle? The insistence that everyone must follow this model is not just ridiculous, but may also kill people since they will rush to the poorly resourced hospitals rather than stay home and minister to this with multiple herbs, concoctions and healing blends known by tradition. The beauty of Ayurveda is its decentralized model—everyone can be a healer in their own homes, with just basic kitchen cabinet ingredients as medicine.

Even Native Americans and African Americans in poor areas of the US will have to tap their own culinary and medicinal heritages, if they are to survive this pandemic without depending on what is essentially an unaffordable healthcare model.

Many Nepali workers have died in New York. They may have lived had they followed their gurus and amchis, rather than going to the hospitals which turned them away without treatment.

Governments of India, Nepal, and Bhutan must support a massive effort to produce Ayurvedic herbs which cure pulmonary and respiratory infections; and not only listen to WHO, UN or any other Eurocentric hegemonic authorities that will insist that traditional healing is “fake news” in order to sustain the illusion of European supremacy to the last breath.

It is clear as this pandemic unfolds that the savage in the heart of human culture may be modern civilization, not the painted tribes of the Amazons who always knew how to cure themselves with berries and roots. The irrational people are the ones who will not listen to evidence, who will continue to do their shamanistic dances in their plastic PPE, murmuring superstitious voodoo chants about non-existent vaccines.

Traditional wisdom triumphs in Nepal

When the coronavirus has spread to nearly every country in the world, why hasn’t it in Nepal? After all, China is just across the border, and one can see many Chinese as well as European tourists in Nepal. Surely someone must have been in contact with someone else who was infected. The situation is certainly curious—so much so that even the politicians have gone on record, asserting confidently: “Coronavirus won’t come to Nepal.”

Why have we avoided the epidemic? This question struck a doctor in Nepal. In an article in Nagarik, Doctor Sher Bahadur Pun hypothesized that the tradition of using one’s hands for eating, dishwashing, laundry, washing after defecation, etc may be pivotal in eliminating the virus. We “play with water” in all our daily activities. Unlike people of developed countries who do not wash hands before eating, people in Nepal wash twice: once before and once after a meal. They also don’t have appliances (or, like me, choose not to use them), so they wash clothes and do dishes by hand. Again, this means a thorough soak in strong soap and water for long at least twice a day. In addition, people use their hands to wash themselves after going to the toilet, and this is followed by a hand wash at least two or three times a day.

Although I bought a washing machine, I never used it. I like using my bucket to soak my clothes overnight, before rinsing them in the morning and hanging them out to dry. My eighty-five-year-old father still washes his underwear and socks himself daily. The thought of piling up used underwear and socks for a once a week laundry always discomforted me, which is why I may have reverted to a daily wash. Although it’s not always possible to do laundry every day—aches and pains, fevers, period blues can strike the body—I find the daily activity of washing one’s clothes gives a sense of work completed. I get this ethics from my mother, who in her seventies still likes to “pacharnu” (thrash) her clothes and give it a sun dry, even if she can’t thoroughly soap and rinse the clothes due to diabetes and high blood pressure.

After reading the Nagarik article, it occurred to me that nobody in the West washes their hands before or after eating. Cutlery has given the West a sense of immunity. They would be appalled at the idea of eating with hands, because they assume their civilizational habits are supreme and there can be no more discussion about this matter. In fact, there’s nothing clean about plastic cutlery that’s been handled multiple times by plastic distributors, restaurant workers, food deliverers and other people on the chain of transmission. Coronavirus survives 3-4 days on plastic, as opposed to four hours on copper. Even when eating with metal cutlery, people in the civilized West are at risk due to their hygiene habits.

There might be small particles of food and saliva on their hands which they may have wiped off with a paper or cloth napkin, but that is not enough to wash away a virus. They walk around confidently afterwards with saliva contaminated and germ-laden hands and handle money, papers, and office equipment. They shake hands and they kiss other people goodbye, touching people’s bodies and clothing with the same fingers they just dipped into the pasta sauce or in half-raw beef sandwich.

“White People, you need to wash your butts: Toilet paper is not enough,” wrote Indi Samarajiva on Medium, bringing lots of laughs and a fair amount of agreement. His laugh out loud funny article argued that not washing one’s butts was dirtier than using toilet paper. Besides toilet paper panic post coronavirus, the article brought to the fore the issue of deforestation. Western notions of sanitation has been one of the most harmful practices for the environment—from toilet paper that deforests entire forests to the flush that consumes eight liters of water, from cleaning chemicals of toxic provenance to sanitary pads made of plastic which clog up waterways. Sanitation Western-style has bulldozed environments worldwide.

Could it be that a reversal to traditional ways of living might be the way to avoid this pandemic, rather than AI or Gilead stocks? In Nepal, people cook their own meals twice a day, eat with their hands, wash before and after eating, wash their dishes and laundry with soap and water every day, rarely go to restaurants, do not use much plastic cutlery, and in general live a simple life in which plastic is minimized. They also practice avoidance of “jutho”—anything touched by saliva or saliva touched hands. They do not accept or offer jutho to others. They don’t shake hands—they do namaste, and in general maintain a respectful distance between people.

All of this was scorned as Brahminical puritanism by the Maoists, who forced Brahmins to eat food from the same plate as strangers under pain of death. Ostensibly meant to be a caste equalizer, as Brahmins don’t share food with other castes, what these forcibly shared meals overlooked is that Brahmins don’t even share food with their own family members— they always respect the right of the other person not to be contaminated by the saliva of someone else.

Will the Eurocentric world listen to this age-old wisdom? Or would they rather die instead?

Coronavirus and Nepal: Imbalance brings disease

All Asian cultures, especially the Chinese, agree disease is caused by an imbalance of elements which make up the human body. Ayurveda recognizes five elements (pancha bhuta) that make up the body. All five elements—air, fire, water, earth, ether—have to be in balance for the body to be healthy. Too much air element can cause joint and bone pains, too much fire element can cause fevers, too much water can cause diarrhea, for instance. Food must always be prepared in a way which balances sattva, rajas and tamas elements for perfect health.

This leads me to theorize that all elements of the environment also have to be in balance for life to be healthy. That is not the case in the current frenetic search for “development.” China is filled with asphalt and concrete, suffocating the earth element. Their factories are fueled by coal and fossil fuel, creating global heating and imbalancing the fire element. Their waterways are overexploited, dammed and full of plastic, destabilizing the water element. Industries spew chemical pollution in the air, imbalancing the air element. CFCs and other dangerous chemicals burn holes into the ozone in the stratosphere, imbalancing the ether element. How then can a dangerous pandemic like the coronavirus not take hold? The environment itself is deranged and out of balance—how can it support healthy life?

Yet this is the same model our communists have triumphantly followed. They don’t want any “feudal” elements in their lives—not the ancient ponds and waterways which were associated with Hindu worship, and which are now buried for building supermalls and commercial complexes; not the forests which sheltered the monkeys and deer of Shiva because they see no profit in taking care of trees and animals; not the temples which hosted ancient gods and goddesses because they are better cleansed for gilded plastic Laughing Buddhas promising prosperity and manufactured in dubious conditions in factories in China.

I was in Patan and aghast to see they’d demolished the Krishna Temple, made of stone and full of carved Vishnus from centuries ago. They had done the same to the JaiBageswori Temple near Pashupati. They are replacing them with shoddy carved imitations which even a first year art student would scorn to make. This is an international art crime that those who are selling and those who are buying will have to pay for, in the not so distant future. Interpol must send out a red alert to catch these criminals.

For Nepali communists, getting rid of two million trees in Kathmandu to widen the roads a few feet has been a triumph of urban planning. Never mind if destruction of greenery has brought severe air pollution, water shortages and a new ominous threat in the form of urban plagues like dengue to the overcrowded city. The feudals were always wrong and always evil, they argue—there is no discussion of how their policies to restrict demographic growth in a small bowl-shaped valley like Kathmandu contained the seeds of urban wisdom, not just social exclusion.

As to how the communists plan to provide water to the rising population of millions there is no answer, other than allowing more and more fossil fueled tankers to go around selling water in plastic canisters, a clearly unsustainable albeit popular strategy which doesn’t have a future in the long run. Will they fund the gravity-fueled dhungay dharas of yore? But there is no tax in that!

How would our comrades make money if they created infrastructure which provided basic services to people at a low or free cost? At the moment, they get to dig up the Melamchi pipes every few months (as they are doing right now in Handigaon). Someone makes a fat profit form this Kafkaesque exercise in digging up a non-existent waterpipe while getting their annual contract from their comrades. I assume this “cake” is cut and shared with the top leaders, not just the local contractor who bid and got the job.

The danger of communism is not just stupidity, which is emptying our country of its cultural heritage, forests and wildlife. It is that their vision of governance is so short sighted, with everything centered around collection of tax and distribution to near and dear ones, that they have created an ecological imbalance of living conditions which makes a pandemic a very real possibility, as we saw with dengue in the summer. Getting rid of them and bringing in a more ethical crew is now a matter of life and death for almost everyone (bar a few) in Kathmandu. Polluted air does not discriminate between rich and poor. Even though your air-conditioned car may carry you through the worst stretch in a seeming environment of pristine air, that security is very, very deceiving.