The Bagmati river is revered as a sacred lifeline, deified for its purifying waters and deeply entrenched cultural and religious significance. It serves as a ritual site for cremation and spiritual cleansing in the pursuit of salvation, embodying the belief that its sacred flow can absolve karma and unite the soul with the divine, forming a transcendent cycle where birth, death and eternity converge.

Flowing through the heart of Nepal’s Kathmandu valley, the Bagmati is more than just a body of water, it’s a sacred thread woven into the spiritual, cultural and ecological fabric of the nation. Revered in both Hindu and Buddhist traditions, it has for centuries been a symbol of civilization, sanctity and continuity, a giver of life and a pathway to salvation.

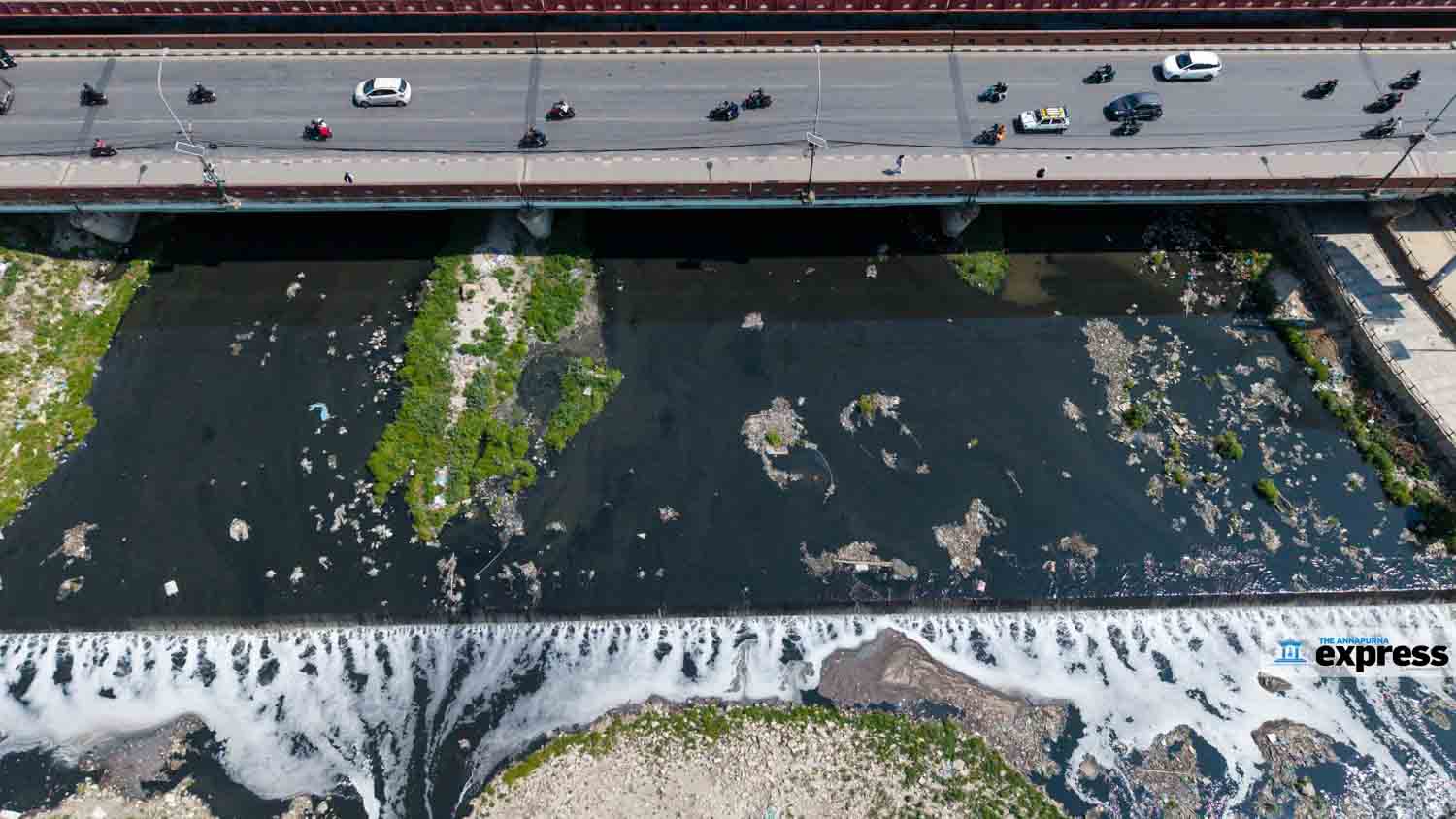

Yet today, the same river that once nourished an entire valley has been reduced to a toxic sewer. Its waters are blackened by sewage, choked with industrial waste and biohazards, and fouled by an unbearable stench. In its putrid current lies a haunting question: Can the Bagmati still be called holy or has it become a public health hazard?

Sacred shrine to sewer stream

The Bagmati river originates from Bagdwar in the Shivapuri Hills of the Mahabharat range at an elevation of 2,690 meters, where it once flowed crystal clear, pure, life-sustaining and revered. It travels southward through the Kathmandu valley (15 percent basin area), descending into the Tarai plains through eight districts before crossing into India to merge with the Ganges. For Hindus, the Bagmati is more than a river, it’s the earthly embodiment of the divine, intimately linked to Lord Shiva at the Pashupatinath Temple, a UNESCO World Heritage since 1979, where its waters are believed to carry souls toward moksha (liberation).

The river, steeped in legend and divine embodiment. According to mythology, the Bagmati began flowing when Bodhisattva Manjushree cleaved the hills surrounding a primordial lake, draining it and making way for human settlement. This act gave birth to the ancient city of Manjupattan on its banks. The Bagmati has served as a spiritual and cultural lifeline shaping early Kathmandu and marking historical trade routes at Teku Dovan and cremation sites such as Kalmochan and Pachali Ghat preserving 3,000 years of ritual heritage and royal legacy.

Today, however, the Bagmati paints a very different picture. Its once-pristine waters are choked with industrial effluents, raw sewage and biohazardous waste, primarily via anthropogenic pressures. A 2017 UN report estimated that over 95 per cent of wastewater in the valley is discharged untreated into natural water bodies much of it ending up in the Bagmati. This unchecked pollution now poses a grave hazard to both environmental and public health hindering water reuse and ecological sustainability.

The riverbanks, once adorned with temples and terraced greenery, are now strewn with plastic bags, decaying waste and the remnants of discarded ritual offerings. Despite the presence of existing and rehabilitated wastewater treatment plants, their capacity remains woefully inadequate to handle the overwhelming waste burden. Key degradation contributors are unmanaged urbanization, indiscriminate waste disposal and the direct discharge of domestic and industrial sewage further exacerbated by poor planning, fragmented governance and the rapidly growing valley population, now nearing 3m. Unlike artificial canals, the Bagmati is a natural river, whose sandy riverbed has been stripped bare by decades of toxic dumping. Though efforts to clean and preserve the river are urgent, the prospect of restoring it to its former sanctity is uncertain. In many respects, the damage may already be irreversible.

Health hazard—a nightmare

The Bagmati river now embodies a profound ecological and public health crisis. Scientific studies have revealed alarming levels of microbial and chemical contamination. A 2019 study published in the journal ‘water’ identified 709 bacterial genera in the river, including 18 potentially pathogenic such as Arcobacter, Acinetobacter and Prevotella. Thakali et al (2020) further detected reservoirs of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs), transformed the Bagmati as a hotspot for antimicrobial resistance (AMR). Shrestha et al. (2023) reported that 80 per cent of river microbial isolates possessed multidrug resistance, while Ghimire et al. (JNHRC 2023) confirmed 241 of 615 coliform samples were resistant to common antibiotics.

Beyond microbial threats, a 2015 study estimated that 70,000 plastic micro- and macro-fragments pass through the river daily. Recent analyses have detected heavy metals like lead and mercury, and carcinogenic compounds capable of causing neurological damage, developmental disorders and organ failure. Despite Nepal’s abundant freshwater sources, cities like Kathmandu suffer from water scarcity. The World Bank 2016 reported 19.8 deaths per 100,000 in Nepal are linked to unsafe sanitation, hygiene and waterborne diseases. The environmental collapse is stark: fish stocks have vanished, aquatic birds are gone, and sludge, algal blooms and chemical foam dominate the landscape. Its decline is a warning not only for Nepal but for the world, a reminder that environmental neglect has irreversible consequences.

Revival possible?

Since 2013, the weekly Bagmati Clean-Up Campaign has mobilized volunteers and raised public awareness, but these efforts remain inadequate against the overwhelming scale of pollution and ecological decline. While new wastewater treatment plants are under construction, the pace of infrastructure development continues to lag behind escalating contamination levels. Legal frameworks to penalize polluters do exist, yet enforcement is weak, and often symbolic. What is urgently needed is a strict implementation of environmental laws, holding industries and hospitals accountable through regular audits and real-time monitoring. Solutions like bioremediation with pollutant-degrading microbes, installation of plastic traps at drainage outlets and widespread adoption of household waste segregation must be prioritized. Equally vital is mobilizing spiritual leadership: religious figures can champion environmental stewardship as a sacred duty and promote eco-conscious rituals.

The Bagmati mirrors Nepal’s soul, sacred, yet deeply wounded. Its revival lies not in miracles, but in unified action, scientific innovation and spiritual responsibility.

A nation that kills its rivers kills its own future. The Bagmati’s fate rests in our hands.